A Comprehensive Review of Tuberculosis: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention, and Research

1. Gulam Ahmed Raza Quadri

2. Rahul Kumar

3. Dr. Samatbek Turdaliev

(1. Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic

2. Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.

3. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic)

Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, remains a major global health challenge despite being preventable and curable. In 2023, TB caused an estimated 1.25 million deaths and 10.8 million new cases, with the highest burden in low- and middle-income countries of South-East Asia, Africa, and the Western Pacific. Social determinants—including poverty, undernutrition, overcrowding, and HIV coinfection—continue to fuel transmission. Drug-resistant TB (MDR/XDR) poses a critical obstacle, as many affected individuals still lack timely access to effective therapy. Current diagnostics rely on rapid molecular assays, culture, and radiology, while emerging tools such as point-of-care nucleic acid tests, host biomarkers, and AI-supported imaging aim to improve detection in resource-limited settings. Standard short-course therapy remains effective for drug-susceptible TB, whereas newer regimens incorporating bedaquiline, linezolid, and pteromalid are advancing treatment of drug-resistant disease and reducing duration for selected patients. Prevention efforts—including BCG vaccination, targeted latent TB infection treatment, and infection-control measures—remain essential but limited by variable vaccine protection and incomplete LTBI implementation. Research priorities focus on improved vaccines, host-directed therapies, shorter regimens, and scalable diagnostics. Achieving TB elimination will require integrating biomedical advances with strengthened health systems and social protection to address the root determinants of TB. This review summarises current evidence across epidemiology, clinical features, diagnostics, treatment, prevention, and emerging innovations.

Keywords: Tuberculosis; Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Epidemiology; Diagnosis; Drug resistance; MDR-TB; XDR-TB; BCG vaccine; GeneXpert; Latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI); Public health.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis has afflicted humans for millennia and remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Recent global surveillance indicates an estimated 10.8 million people developed TB in 2023 (95% UI: 10.1–11.7 million), producing about 134 incident cases per 100,000 population; TB caused approximately 1.25 million deaths in 2023 (excluding HIV-associated mortality), with an additional roughly 161,000 deaths among people living with HIV. The geographic distribution is highly skewed: the WHO regions of South-East Asia, Africa and the Western Pacific together accounted for the majority of cases in 2023, with South-East Asia alone comprising about 45% of global incidence. A small group of high-burden countries—India, Indonesia, China, the Philippines, Pakistan and several sub-Saharan African nations—contribute most of the global caseload. Despite measurable gains (for example, some countries have reported declines in incidence since 2015), the absolute number of people falling ill remains unacceptably high and progress toward the WHO End TB targets is uneven.

Key drivers of persistent transmission and poor outcomes are social and structural: poverty, undernutrition, overcrowded and poorly ventilated housing, limited access to quality health services, and the intersecting HIV epidemic. Comorbidities such as diabetes and tobacco use increase risk of progression from latent infection to active disease and reduce treatment success. Moreover, drug resistance—multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB)—poses escalating clinical and programmatic challenges. Only a fraction of estimated drug-resistant cases are detected and treated appropriately, creating reservoirs for ongoing transmission and amplifying morbidity and mortality. Global financing shortfalls and uneven access to molecular diagnostics and novel medicines further limit the reach of effective interventions.

Given this landscape, contemporary TB control must integrate robust public-health measures (case-finding, contact investigation, LTBI management), accessible and rapid diagnostics, evidence-based treatment regimens (including newer shorter options for drug-resistant disease), infection-control practices, social supports to ensure adherence, and accelerated research on vaccines and host-directed therapies. The remainder of this article reviews the pathogen and pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, modern diagnostic algorithms, therapeutic strategies for drug-sensitive and drug-resistant disease, prevention and public-health approaches, and promising research avenues.

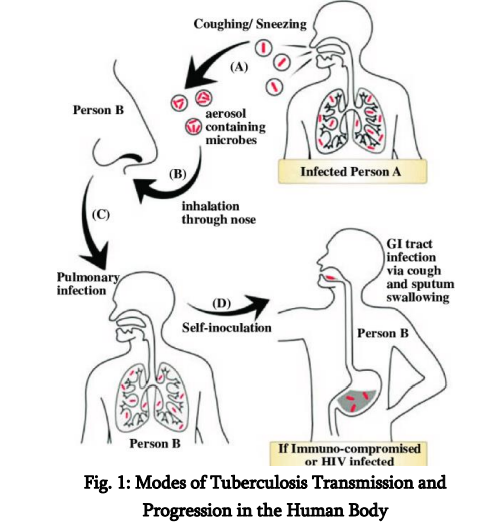

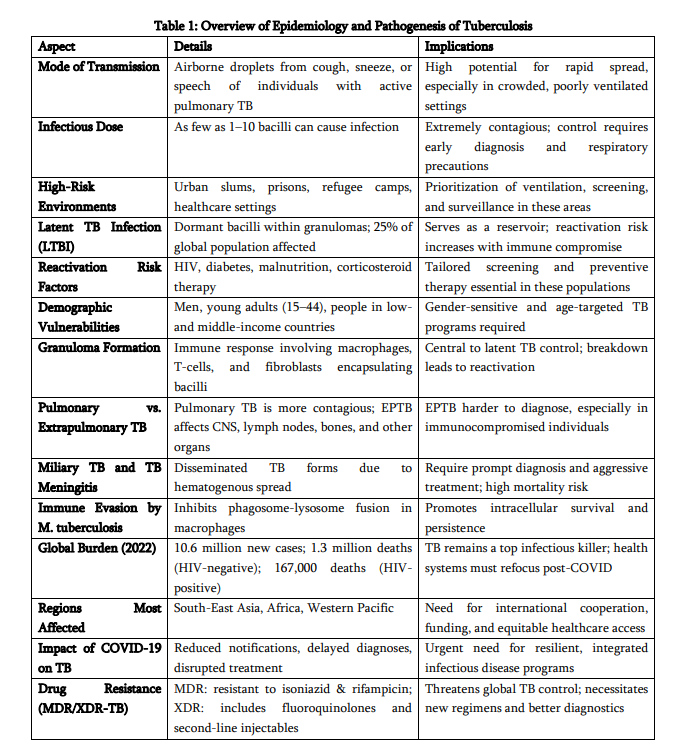

The spread of tuberculosis occurs mainly through the air, rendering it extremely infectious in densely populated or inadequately ventilated environments. The inhalation of contaminated droplets resulting from coughing, sneezing, or verbal communication facilitates the entry of M. tuberculosis into the alveoli of the lungs, where it is subsequently engulfed by alveolar macrophages. The microorganism’s capacity to obstruct the fusion of phagosomes and lysosomes enables its survival and proliferation within host cells, resulting in the development of granulomas— structured immune formations designed to confine the infection. Although a majority of infected persons transition into a latent TB infection (LTBI) phase, characterised by the presence of dormant bacteria that are neither active nor contagious, around 5–10% may advance to active TB disease. This progression is particularly prevalent among individuals with weakened immune systems, including those affected by HIV/AIDS, diabetes, malnutrition, or those receiving immunosuppressive treatments. The worldwide spread of tuberculosis is markedly imbalanced. The regions of South-East Asia and Africa carry the most substantial loads, with nations like India, China, Indonesia, and the Philippines playing a major role in the worldwide tally of cases (WHO, 2023). In these nations, disparities in socioeconomic status, insufficient healthcare systems, nutritional deficiencies, substandard living conditions, and restricted access to prompt diagnosis and treatment intensify the proliferation and consequences of tuberculosis.

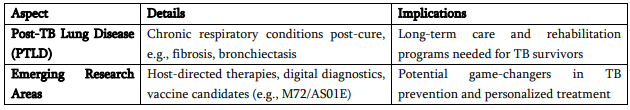

The co-occurrence of HIV and tuberculosis remains a significant concern for public health; in the year 2022, 8% of all tuberculosis instances worldwide were found inindividuals living with HIV, with the African region representing an unequal portion (UNAIDS, 2020). The interplay between these co-epidemics amplifies their impact, as HIV markedly heightens the likelihood of TB reactivation and advancement, whereas TB continues to be the foremost cause of mortality among individuals living with HIV. A significant challenge in the battle against tuberculosis is the rise of drug-resistant variants, especially multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB). MDR-TB, characterised by resistance to at least isoniazid and rifampicin, impacted more than 465,000 individuals worldwide in 2019. Meanwhile, XDR-TB presents an even more significant danger owing to its resistance against fluoroquinolones and second-line injectable medications (Falzon et al., 2017). These resilient variants pose greater challenges and costs for treatment, frequently necessitating extended therapies accompanied by significant adverse effects, consequently deteriorating patient prognoses and elevating mortality rates. Although the BPaLM treatment protocol (bedaquiline, pretomanid, linezolid, and moxifloxacin) has demonstrated potential in shortening the treatment period to 6 months, issues related to availability and expense continue to pose considerable challenges in numerous high-burden areas (Conradie et al., 2022). The COVID-19 outbreak has added layers of complexity to worldwide tuberculosis management initiatives. Healthcare systems faced immense strain, leading to interruptions in diagnostic and therapeutic services, while resources were reallocated, causing notable declines in tuberculosis detection and reporting. The Global TB Report 2021 recorded a decline in newly identified TB cases for the first time in more than ten years—a regression directly linked to the pandemic. This decline presents significant challenges for realising the WHO’s End TB Strategy, which targets a 90% decrease in TB fatalities and an 80% reduction in TB cases by the year 2030 (WHO, 2021). From a medical perspective, tuberculosis presents in various manifestations. The prevalent form, pulmonary tuberculosis, manifests through a continual cough (extending beyond two weeks), discomfort in the chest, coughing up blood, elevated temperature, nocturnal sweating, loss of weight, and exhaustion. Nonetheless, extrapulmonary tuberculosis—impacting organs like the lymphatic system, cerebral region, renal system, and skeletal structure—is gaining recognition, particularly among those with weakened immune systems. Tuberculous meningitis, for instance, represents one of the most critical extrapulmonary manifestations, frequently resulting in permanent neurological impairment or fatality if not addressed (Seddon et al., 2019). Childhood tuberculosis necessitates unique attention, as young patients frequently exhibit vague symptoms, resulting in postponed diagnoses and increased mortality rates within this demographic. Initiatives aimed at enhancing tuberculosis diagnosis have progressed significantly over the last ten years. Conventional methods such as sputum smear microscopy are being supplanted by advanced molecular diagnostic approaches like GeneXpert MTB/RIF, which facilitates swift identification of tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in just a matter of hours. Moreover, the incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) in the analysis of chest radiographs, especially in environments with limited resources, has the capacity to enhance diagnostic precision and alleviate the workload on radiologists (Qin et al., 2021). Interferon-Gamma Release Assays (IGRAs) and tuberculin skin tests (TST) are commonly employed to identify latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI), particularly in healthcare professionals and individuals with HIV. However, these methods are unable to distinguish between latent and active tuberculosis disease. Regarding preventive measures, the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine remains in use for infants in regions where tuberculosis isprevalent, providing defence against serious paediatric manifestations of the illness, including miliary tuberculosis and tuberculosis meningitis. Nonetheless, its restricted effectiveness in averting pulmonary tuberculosis in adults has sparked continuous investigation into advanced TB vaccines, like M72/AS01E, which exhibited a 50% success rate in a phase IIb trial (Schrager et al., 2020). Moreover, public health initiatives such as contact tracing, proactive case identification, and community involvement play a crucial role in managing the transmission of tuberculosis. Mobile health innovations, educational initiatives, and digital compliance tracking systems are demonstrating significant effectiveness in lowering treatment abandonment rates, especially in resource-limited regions (Masini et al., 2016). In addition to medical treatments, the societal factors influencing tuberculosis—such as economic hardship, cramped living conditions, inadequate nutrition, social stigma, and restricted healthcare access—need to be tackled to achieve sustainable advancements. Tuberculosis is not merely a health condition; it is also a manifestation of social disparity, significantly impacting underprivileged groups including migrants, incarcerated individuals, and those without stable housing (Davidson et al., 2024). Consequently, a successful tuberculosis control approach must encompass collaboration across various sectors, implementation of social protection initiatives, and enhancement of health systems to address systemic obstacles to care.

Epidemiology

Global burden and trends: The WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2024 (reporting 2023 data) estimated ~10.8 million incident TB cases and ~1.25 million deaths. Reported case notifications have increased in recent years—partly reflecting recovery of diagnostic services after COVID-19 disruptions and expanded use of molecular tests—but the fraction of all incident cases that are diagnosed and treated still falls short of targets. Regional burdens are concentrated: South-East Asia (~45% of cases), Africa (~24%), and the Western Pacific (~17%), with the Eastern Mediterranean, the Americas and Europe accounting for smaller shares. High-burden countries continue to include India, Indonesia, China, the Philippines and Pakistan, among others.

Drug resistance. MDR-TB (resistance to at least isoniazid and rifampicin) and XDR-TB remain critical threats. Global estimates indicate hundreds of thousands of MDR/RR (rifampicin-resistant) cases annually, but detection and appropriate treatment coverage remain insufficient—often below 50% in many settings—allowing ongoing transmission of resistant strains and complicating programmatic response.

Vulnerable populations: The highest burdens are observed among socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, people living with HIV (who have markedly elevated risk of progression and mortality), prisoners, migrants, and people with comorbidities (e.g., diabetes). Urban overcrowding and healthcare access gaps further concentrate risk in marginalised communities.

Pathogenesis

Understanding TB Transmission Tuberculosis (TB) predominantly affects the respiratory system, spreading via airborne droplets that harbour Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.tb) bacilli. When a person with active pulmonary tuberculosis coughs, sneezes, laughs, or even converses, they emit infectious droplet nuclei into the atmosphere, which can linger for hours—particularly in enclosed, inadequately ventilated spaces. Breathing in just a few bacilli could be enough to trigger an infection, especially in individuals with weakened immune systems or those who have been exposed for extended periods (Davidson et al., 2024). High-transmission environments include: · Overcrowded homes and urban slums · Prisons and detention centers · Homeless shelters · Hospitals and healthcare facilities, especially with poor infection control (Masini et al., 2016; Kaur et al., 2024)

The spread of disease is significantly shaped by various social factors affecting health, including economic hardship, malnutrition, high population density, and restricted availability of healthcare ervices. People with latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) carry the bacteria in an inactive form, exhibiting no symptoms and posing no risk of spreading the disease. Nonetheless, around 5–10% of people with latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) may advance to active disease during their lifetime, with this risk significantly heightened in situations of immune compromise (Esmail et al., 2018; Bruchfeld et al., 2015). Groups that are particularly vulnerable to advancing from latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) to active tuberculosis (TB) encompass: • Persons affected by HIV/AIDS (the co-occurrence heightens the risk by 18 to 20-fold) (Gelaw et al., 2019; Bruchfeld et al., 2015) · Individuals diagnosed with diabetes mellitus (Alemu et al., 2021; Yorke et al., 2017) · Under-nourished persons · Individuals receiving immunosuppressive therapies like TNF-α blockers (Zhang & Yew, 2015; Nahid et al., 2016) Factors such as gender, age, and profession significantly influence the dynamics of transmission. Men have a greater likelihood of developing tuberculosis compared to women, which can be attributed to elevated levels of smoking, alcohol consumption, and exposure in the workplace (Zumla et al., 2015). The demographic of individuals aged 15 to 44 years continues to be the most frequently impacted group, frequently as a result of heightened exposure within the community and restricted access to healthcare services (Furin, Cox, & Pai, 2019).

While pulmonary tuberculosis is the most contagious variant, extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) is gaining recognition, especially among those with weakened immune systems. Types of extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) encompass tuberculous meningitis, lymph node infection, skeletal tuberculosis (known as Pott’s disease), pleural fluid accumulation, and genitourinary tuberculosis. These conditions present greater diagnostic challenges

TB Pathogenesis The development of tuberculosis involves a complex interplay between the bacterium M. tuberculosis and the immune defences of the host. The adventure commences as aerosolised bacilli are breathed in and arrive at the alveoli within the lungs. In that location, they are engulfed by local alveolar macrophages, serving as the initial line of immune defence. In contrast to numerous other bacterial species, M. tuberculosis has developed intricate strategies to avoid annihilation within macrophages. It obstructs the fusion of phagosomes and lysosomes, hinders the acidification process within the phagosome, and alters the signalling pathways of host cells to establish a favourable intracellular environment that allows for undetected replication (Flynn & Chan, 2001; Gygli et al., 2017). The immune system of the host identifies the infection and triggers a T-helper 1 (Th1)-driven response, marked by the generation of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), which stimulates macrophages to eliminate intracellular bacteria. This results in the development of granulomas—a defining characteristic of tuberculosis. Granulomas are structured formations made up of infected macrophages, Langhans giant cells, epithelioid cells, and lymphocytes, encased within a fibrous capsule. Their objective is to "isolate" the infection and hinder its spread (Schrager et al., 2020; Esmail et al., 2018). In the majority of immunocompetent persons, this leads to a latent tuberculosis infection, during which the bacilli stay inactive yet alive, occasionally for many years. As host immunity diminishes—whether from HIV co-infection, nutritional deficiencies, malignancies, or medically induced immunosuppression—the integrity of the granuloma may decline, resulting in the reactivation of tuberculosis. The caseous core of granulomas undergoes liquefaction, resulting in the formation of necrotic spaces within lung tissue. These spaces create an oxygen-abundant setting perfect for bacterial proliferation and allow bacteria to infiltrate the airways, greatly enhancing their ability to spread (McShane, 2015; Nahid et al., 2016). Pulmonary tuberculosis, particularly in its cavitary variant, poses a significant challenge both clinically and epidemiologically. Extrapulmonary manifestations occur when bacilli leave the pulmonary setting through lymphatic or haematogenous dissemination. Miliary tuberculosis, for example, is marked by the existence of tiny, millet-seed-shaped lesions dispersed across the lungs and various other organs. It frequently manifests in individuals with weakened immune systems and is linked to elevated mortality rates (Seddon et al., 2019). Tuberculous meningitis, a serious form of the disease, entails the infection of the protective membranes surrounding the brain and is particularly prevalent among young children and those living with HIV. In the absence of prompt identification and intervention, it can result in permanent neurological harm or fatality (McShane, 2015; Gopalaswamy et al., 2020). Additionally, contemporary research has redirected attention to host-directed therapies (HDTs), which aim to adjust the immune response instead of directly eliminating the bacteria. The reasoning behind this is that managing inflammatory harm and re-establishing immune equilibrium can avert tissue degradation and improve the elimination of bacteria. Instances encompass the reapplication of medications such as metformin, statins, and immune checkpoint blockers for the treatment of tuberculosis (Tiberi et al., 2022; Schrager et al., 2020).

Global TB

Trends In spite of over a hundred years of progress in medicine, tuberculosis remains a prominent contributor to infectious disease fatalities across the globe. According to the WHO Global TB Report (2023), approximately 10.6 million individuals were diagnosed with TB in 2022, resulting in 1.5 million fatalities, among which were 167,000 individuals living with HIV. Tuberculosis has now overtaken HIV/AIDS as the primary cause of mortality attributed to a single infectious agent (WHO, 2023). These disheartening figures highlight not just the enduring nature of TB but also the worldwide inadequacy in executing fair healthcare and public health measures. The geographical distribution of tuberculosis is markedly uneven. Almost 70% of all tuberculosis cases are found in the South-East Asian and African regions. Nations such as India, China, Indonesia, Pakistan, Nigeria, and the Philippines persist in documenting the most elevated incidence rates, influenced by high population densities, restricted healthcare access, nutritional deficiencies, and inadequately financed tuberculosis control initiatives (WHO, 2023; Floyd et al., 2018). Disparities between rural and urban areas continue to exist, with urban slums and rural backlands acting as breeding grounds for tuberculosis, attributed to factors such as overcrowding, inadequate ventilation, and insufficient monitoring systems (Chatterjee & Pramanik, 2015).

Diagnosis and Screening

The identification of tuberculosis (TB) is fundamental to successful management approaches, but it continues to be laden with practical difficulties, particularly in environments with limited resources. Timely and precise identification is essential not just for the care of individual patients but also for interrupting the transmission cycle within the community (World Health Organisation, 2023; Floyd et al., 2018). The traditional method has depended on sputum smear microscopy, a technique that was established over a hundred years ago. While being cost-effective and fairly straightforward to execute, it is hindered by limited sensitivity—especially in individuals co-infected with HIV, young children, and those with extrapulmonary tuberculosis (Pai et al., 2017; Chatterjee & Pramanik, 2015). Furthermore, smear microscopy is unable to differentiate between Mycobacterium tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacteria (Sharma & Upadhyay, 2020). In order to overcome these constraints, cultural techniques like Löwenstein-Jensen (solid medium) and MGIT (liquid medium) are regarded as more sensitive, albeit requiring a considerable amount of time, often taking several weeks to yield results (Boehme et al., 2010; Gygli et al., 2017). These techniques continue to be the benchmark for validating diagnoses and assessing drug resistance. Nonetheless, in areas with significant burdens where time is of the essence and laboratory facilities are insufficient, the lag can result in fatal outcomes (Masini et al., 2016; Tiberi et al., 2022). The emergence of molecular diagnostics has been revolutionary. The GeneXpert MTB/RIF test, supported by the WHO, transformed tuberculosis diagnosis by providing outcomes in less than two hours while concurrently identifying rifampicin resistance (Boehme et al., 2010; World Health Organisation, 2021). This real-time PCR assay proves to be particularly beneficial in identifying smearnegative and extrapulmonary instances, which frequently elude traditional detection methods. The latest Ultra iteration enhances sensitivity to an even greater extent, detecting TB in paediatric patients and those infected with HIV who present with paucibacillary disease (Fox et al., 2013; Bruchfeld etc.

REFERENCES

[1].World Health Organisation. Global Tuberculosis Report 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/97892 40076729

[2]. Esmail, H., et al. (2018). Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 4(1):27.

[3]. Flynn, J. L., & Chan, J. (2001). Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2(7), 568–578. [4]. Boehme, C. C., et al. (2010). Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics, 10(9), 987–993.

[4]. Conradie, F., et al. (2022). Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 10(2), 144–155.

[5]. Zumla, A., et al. (2015). The Lancet InfectiousDiseases, 15(4), 414–426.

[6]. Fox, G. J., et al. (2013). IJTLD, 17(6), 603–612.

[7]. Schrager, L. K., et al. (2020). Nature ReviewsImmunology, 20(9), 555–562.

[8]. World Health Organization. (2021). Global Tuberculosis Report 2021. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/teams/globaltuberculosis-programme/tb-reports

[9]. Lawn, S. D., & Zumla, A. I. (2011). Tuberculosis. The Lancet, 378(9785), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62173-3

[10]. World Health Organization. (2021). Tuberculosis: Key facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/tuberculosis

[11]. Esmail, H., Barry III, C. E., Young, D. B., & Wilkinson, R. J. (2018). The ongoing challenge of latent tuberculosis. The New England Journal of Medicine, 379(14), 1356–1366. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1800837

[12]. Dheda, K., Barry III, C. E., & Maartens, G.(2019). The epidemiology of tuberculosis: A global perspective. Clinics in Chest Medicine, 40(4), 653–677.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2019.08.001

[13]. Pai, M., Schito, M., Migliori, G. B., & Loddenkemper, R. (2017). Tuberculosis diagnostics: Challenges and opportunities. Microbiology Spectrum, 5(1), TNMI7-0030-2016. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7- 0030-2016

[14]. Nahid, P., Dorman, S. E., Alipanah, N., Barry,P. M., Brozek, J. L., Cattamanchi, A., ... & Menzies, D. (2016). Official American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society ofAmerica clinical practice guidelines: Treatment of drug-susceptible tuberculosis. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 63(7), e147–e195. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw376

[15]. Gygli, S. M., Borrell, S., Trauner, A., & Gagneux, S. (2017). Antimicrobial resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Mechanistic and evolutionary perspectives. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 30(4), 887–920. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00057-16