Autoimmune Adrenalitis: A Deep Dive into Pediatric Addison’s Disease

1. Gulnaz Osmonova

2. Vikram

(1. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic

2. Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.)

Abstract

Primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI; Addison’s disease) in children is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening endocrinopathy characterized by failure of the adrenal cortex to produce glucocorticoids and often mineralocorticoids. In developed countries the most frequent etiology in the pediatric population is autoimmune adrenalitis, frequently associated with autoantibodies against steroid 21-hydroxylase and with other autoimmune conditions such as autoimmune thyroid disease and type 1 diabetes as part of autoimmune polyglandular syndromes (APS). Early recognition is crucial to prevent adrenal crisis and to institute lifelong replacement therapy with hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone when indicated. This review summarizes pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnostic evaluation, differential diagnosis, management (acute and long term), monitoring, genetic associations and future directions relevant to MBBS/PG trainees and pediatric clinicians.

Keywords: Autoimmune adrenalitis, pediatric Addison’s disease, primary adrenal insufficiency, autoimmune polyglandular syndrome, 21-hydroxylase antibodies, adrenal crisis, pediatric endocrinology, glucocorticoid deficiency, mineralocorticoid deficiency, hydrocortisone replacement therapy.

Introduction

Addison’s disease refers to chronic primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) due to destruction or dysfunction of the adrenal cortex resulting in deficiency of cortisol and, frequently, aldosterone. While PAI is rare in children relative to adults, it carries significant morbidity and mortality, especially when presenting acutely as an adrenal crisis. Autoimmune adrenalitis is the predominant cause of PAI in developed regions and should be suspected in any child with suggestive symptoms or signs, particularly when associated autoimmune conditions exist.

Epidemiology

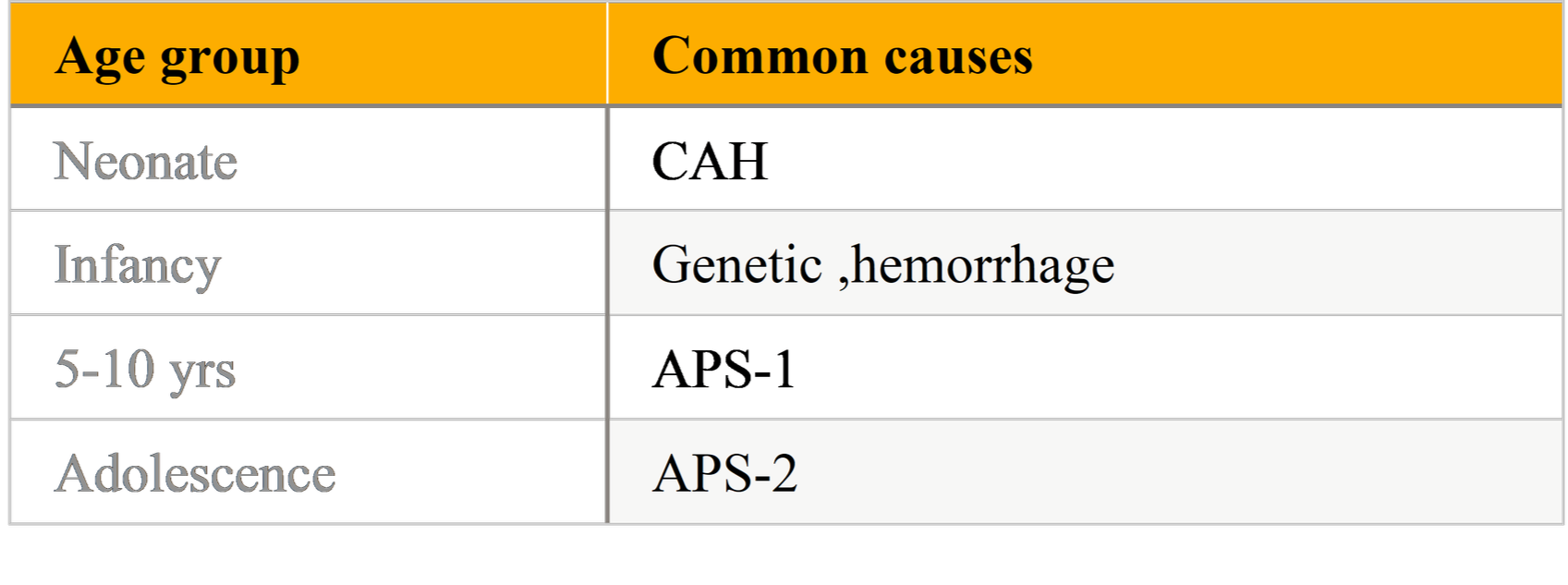

PAI is uncommon in the pediatric population; incidence estimates vary by region and ascertainment method. In Western/developed countries autoimmune mechanisms account for the majority of non-congenital cases and 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies are detectable in a high proportion of affected children. Neonates and infants more commonly present with inborn errors (e.g., congenital adrenal hyperplasia) or adrenal hemorrhage, whereas older children and adolescents are more likely to have autoimmune or genetic/monogenic causes (APS-related). Population cohort studies and registry analyses show regional variation

Etiology and Pathogenesis:

Table: Age wise Etiology of Pediatric Primary Adrenal Insufficiency:

Autoimmune Mechanisms:

Autoimmune adrenalitis is mediated by cellular and humoral responses that target steroidogenic enzymes within the adrenal cortex — most prominently 21-hydroxylase (CYP21A2). Circulating autoantibodies to 21-hydroxylase are a useful diagnostic marker and are present in the majority of autoimmune PAI cases in children in developed settings. T-cell mediated destruction of adrenal cortical tissue causes progressive loss of cortisol and aldosterone production.

Genetic Associations

Genetic predisposition influences susceptibility. HLA haplotypes (e.g., HLA-DR3, DR4) are associated with autoimmune PAI. Monogenic syndromes—most notably APS-1 (autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1, APECED) due to mutations in the AIRE gene—cause adrenal failure as part of multi-endocrine autoimmunity and tend to present in childhood or adolescence. APS-2 is polygenic and often presents later; it includes combinations of autoimmune adrenalitis, autoimmune thyroid disease and type 1 diabetes. Genetic testing should be considered when APS or familial patterns are suspected.

Environmental Triggers

Infectious causes (e.g., tuberculosis) and bilateral adrenal hemorrhage can produce PAI, but in many developed settings these are now less frequent than autoimmune disease. Environmental triggers interacting with genetic susceptibility likely initiate autoimmunity in predisposed individuals.

Autoimmune Polyglandular Syndromes (APS)

APS comprises syndromic clusters of autoimmune endocrine disorders. Relevant types include:

APS-1 (APECED): Autosomal recessive AIRE mutations. Classic triad: chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, hypoparathyroidism, and adrenal insufficiency (often by childhood/adolescence)

APS-2: Polygenic, HLA-associated; more frequent than APS-1 and includes adrenal insufficiency with autoimmune thyroid disease and/or type 1 diabetes. Onset typically in adolescence or adulthood but may present in older children.

Recognition of APS is vital because early screening for associated autoimmune diseases (thyroid, diabetes, celiac disease, hypoparathyroidism) allows proactive management and avoids missed morbidity.

Clinical Presentation in Children:

Chronic/subacute features:

Symptoms are often nonspecific and insidious:

Fatigue, lethargy, anorexia, weight loss.

Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain—can lead to misdiagnosis as gastroenteritis. Hyperpigmentation (in primary adrenal failure) — especially in mucous membranes, palmar creases, scars — due to elevated ACTH and proopiomelanocortin peptides. Salt craving, orthostatic dizziness, hypotension.

Failure to thrive, poor growth, delayed puberty in chronic untreated cases. Hyponatremia and hyperkalemia may be present.

Adrenal (Addisonian) crisis:

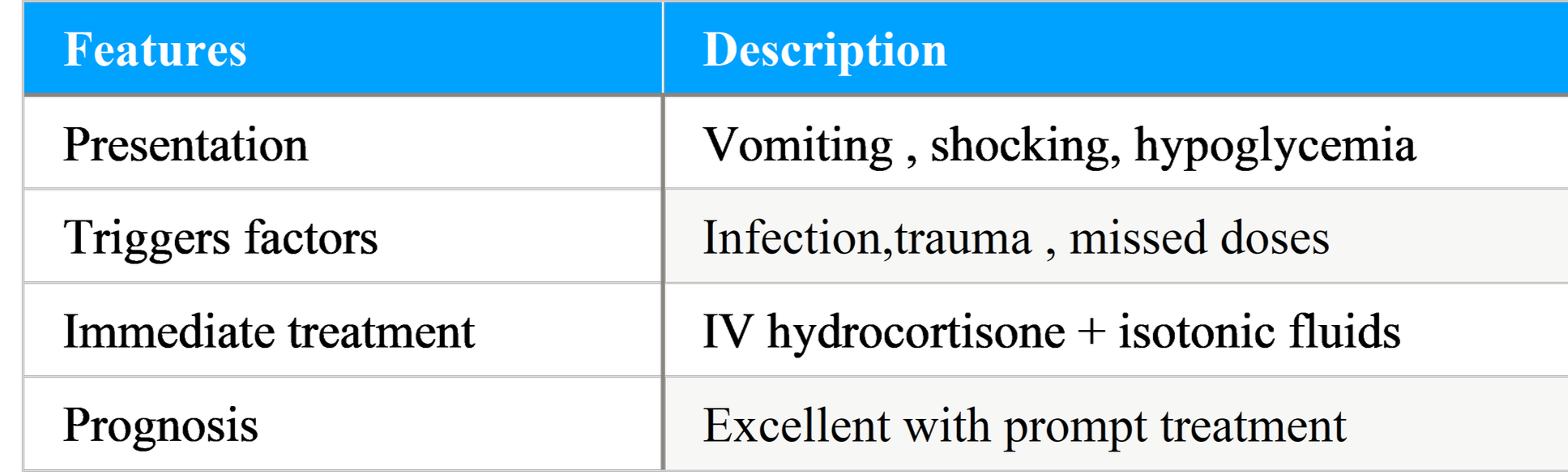

A life-threatening emergency with: severe vomiting, dehydration, hypotension/shock, electrolyte derangements (hyponatremia, hyperkalemia), hypoglycemia (more common in children), altered sensorium. Triggers include infection, trauma, surgery, or abrupt withdrawal of glucocorticoids (in patients on exogenous steroids with adrenal suppression). Prompt recognition and immediate treatment with IV hydrocortisone and fluid resuscitation are lifesaving.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Clinical suspicion

Consider PAI in any child with unexplained chronic fatigue, hyperpigmentation, unexplained vomiting with weight loss, or recurrent hypoglycemia; suspect adrenal crisis with hypotension, shock, and electrolyte abnormalities.

Baseline laboratory evaluation:

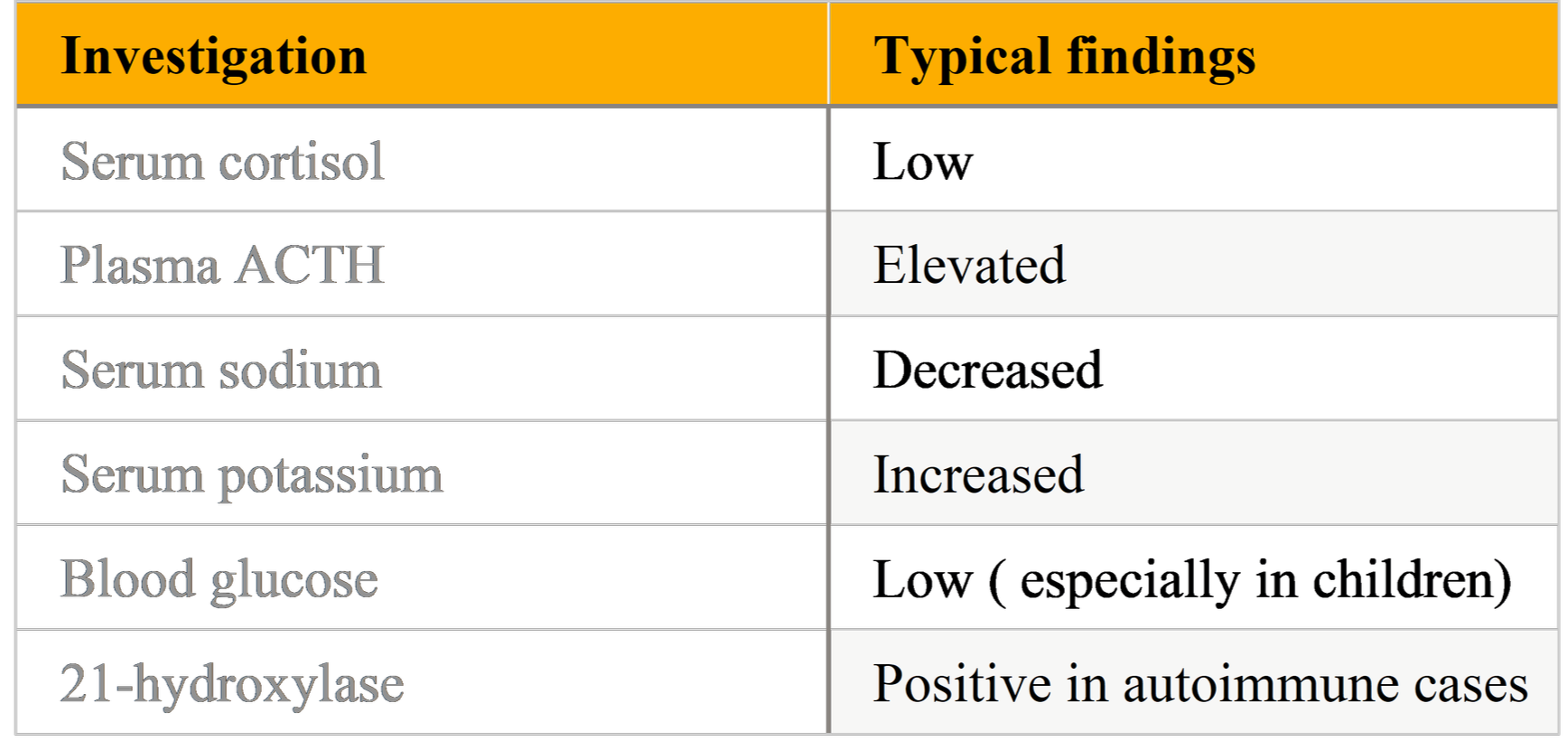

Serum cortisol and plasma ACTH (random morning preferred): low cortisol with elevated ACTH indicates primary AI. Note that a single random cortisol can be difficult to interpret; values must be contextualized to the clinical scenario.

Electrolytes: hyponatremia, hyperkalemia (suggest mineralocorticoid deficiency); hypoglycemia may be present in children.

ACTH stimulation (cosyntropin) test: the standard confirmatory test in many settings: inadequate cortisol response after ACTH indicates adrenal insufficiency. Some pediatric protocols use low- dose (1 µg) cosyntropin or standard 250 µg depending on age and lab recommendations.

Etiologic workup:

21-hydroxylase autoantibodies (anti-CYP21A2): positivity confirms autoimmune adrenalitis in many cases and mandates screening for other autoimmune disorders. Studies report high positivity rates in pediatric autoimmune PAI.

Genetic testing: for infants or those with family history or syndromic features (AIRE gene for APS-1, other monogenic causes).

Infectious screening: TB testing/imaging when clinically indicated or in endemic regions.

Adrenal imaging (CT/MRI): reserved for atypical presentations, suspicion of hemorrhage, infiltrative disease, or to rule out mass lesions.

Differential Diagnosis:

Secondary (central) adrenal insufficiency: due to pituitary/hypothalamic disease — features differ (no hyperpigmentation, usually no hyperkalemia).

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH): 21-hydroxylase deficiency often presents in neonates with ambiguous genitalia (46,XX), salt-wasting crisis, or later testosterone excess. Distinguished by newborn screening, elevated 17-hydroxyprogesterone and genetic testing. Adrenoleukodystrophy (X-linked): progressive neurologic signs with adrenal failure in boys — consider plasma very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA) testing. Infections, hemorrhage, metastatic or infiltrative disease.

Management

Acute management — adrenal crisis:

The adrenal crisis is a medical emergency:

1. Immediate resuscitation: ABCs, secure airway if necessary, high-flow oxygen, IV access.

2. IV fluid resuscitation: isotonic saline boluses (20 mL/kg) repeated as needed for hypotension and dehydration.

3. Empiric IV hydrocortisone: initial 50–100 mg/m² IV bolus (or 2 mg/kg up to 100 mg in children) followed by 50–100 mg/m²/day divided q6–8h as continuous infusion or boluses depending on local protocols. Replace glucose if hypoglycemic. Empiric steroids should not be delayed for diagnostic tests.

4. Electrolyte correction and monitoring: treat hyperkalemia promptly. Mineralocorticoid replacement (fludrocortisone) can be started after stabilization (not required acutely if high-dose hydrocortisone is given because hydrocortisone has mineralocorticoid activity at high doses).

Chronic replacement therapy:

Glucocorticoid replacement: Hydrocortisone is the preferred agent in children due to more physiologic profile and lesser growth suppression risk compared to potent synthetic glucocorticoids. Typical maintenance dosing ranges widely; many pediatric endocrinology sources recommend approximately 9–12 mg/m²/day divided into 2–3 doses (morning, midday, sometimes late afternoon) tailored to clinical response and growth. Recent pediatric reviews and practice guidance increasingly support individualized dosing and attention to mimicry of physiologic circadian rhythm.

Mineralocorticoid replacement: Fludrocortisone (typical doses 0.05–0.2 mg/day in children, titrated to blood pressure, electrolytes and plasma renin activity) for patients with aldosterone deficiency. Sodium supplementation may be needed in infants.

Stress dosing: Education on stress dosing is essential. During febrile illness, vomiting, surgery, or trauma, hydrocortisone doses are increased (e.g., doubling or tripling maintenance oral dose for minor illness; parenteral dosing for inability to take oral medication). Families should be trained in intramuscular (IM) hydrocortisone administration and carry emergency steroid cards.

Monitoring and follow-up:

Growth monitoring, symptom review, blood pressure, electrolytes, and renin levels when on fludrocortisone.

Periodic screening for associated autoimmune disorders (TSH, fasting glucose, tissue transglutaminase IgA for celiac disease when indicated).

Education on sick-day rules, emergency identification, and steroid emergency kits. Advocacy for school and activity accommodations when needed.

Special considerations in Pediatrics:

Growth and puberty:

Excess glucocorticoid exposure can impair linear growth and affect bone health; therefore dosing should be as physiologic as possible. Use the lowest effective hydrocortisone dose and monitor growth velocity closely. Consider pediatric endocrinology referral for dose-optimization and long- term care.

Neonatal presentation:

In neonates, CAH is the commonest cause of PAI; autoimmune causes are rare in the neonatal period. Salt-wasting crisis requires urgent recognition and management. Newborn screening programs for CAH allow early detection in many countries.

APS-1 and genetic counseling:

Children diagnosed with APS-1 should undergo genetic counseling, family testing where indicated, and early surveillance for the classical triad (candidiasis, hypoparathyroidism, adrenal insufficiency). Early identification of non-endocrine manifestations facilitates multidisciplinary care.

Recent Advances and Research Directions: Autoantibody screening: Early detection of 21-hydroxylase antibodies in at-risk individuals (e.g., relatives of PAI patients, patients with another autoimmune disease) offers opportunities for close monitoring and earlier diagnosis. Some centers monitor at-risk subjects longitudinally.

Modified-release hydrocortisone formulations: Chronocort® and Plenadren® (modified-release formulations) aim to better reproduce circadian cortisol profiles; pediatric data are emerging and may benefit patients with poor symptom control despite standard therapy. Use in children is evolving.

Genetic diagnostics: Next-generation sequencing panels improve detection of monogenic causes of PAI and guide family counseling and prognosis.

Immune modulation: While speculative, research into immunomodulatory therapies to halt autoimmune destruction is ongoing in other autoimmune endocrinopathies; this remains experimental for autoimmune adrenalitis. Future disease-modifying approaches would transform management if proven safe and effective.

Tables and Figures:

Table:Laboratory Findings in Primary Adrenal Insufficiency

Table : Addisonian Crisis: Clinical Features and Management:

Practical Clinical Pearls:

Always consider PAI in a child with recurrent vomiting, weight loss, hyperpigmentation, hypotension, or unexplained hypoglycemia.

Do not delay empiric glucocorticoid therapy in a suspected adrenal crisis—treatment is lifesaving and should not wait for confirmatory tests.

Order morning cortisol and ACTH before giving steroids whenever clinically safe — but if the child is critically unwell, start empiric therapy first.

Test for 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies in suspected autoimmune cases to confirm etiology and prompt screening for other autoimmune diseases.

Counsel families on stress dosing, emergency IM hydrocortisone, and the importance of medical alert identification.

Prognosis:

With timely diagnosis and appropriate lifelong replacement therapy, children with autoimmune adrenalitis can have good quality of life. Vigilance for adrenal crises, appropriate stress dosing, and screening for associated autoimmune comorbidities are essential. Long-term concerns include growth effects from glucocorticoid excess and the burden of managing chronic disease and multiple autoimmune conditions in APS.

How to Approach a Case:

1. Presentation: A 12-year-old with fatigue, weight loss, hyperpigmentation and episodes of dizziness. Check vitals (orthostatic BP).

2. Initial labs: Serum sodium low, potassium high, random cortisol low, ACTH elevated — suspect primary AI.

3. Stabilize if required: If hypotensive or shocky, start IV fluids and IV hydrocortisone immediately.

4. Confirmatory testing: ACTH stimulation test when patient stable. Send anti-21-hydroxylase antibodies, screen TSH, fasting glucose, celiac serology if indicated.

5. Start chronic therapy: Hydrocortisone replacement; fludrocortisone if aldosterone deficiency evident; arrange patient/family education.

6. Follow-up: Monitor growth, BP, electrolytes, screen for other autoimmune conditions. Consider genetic testing if APS suspected.

Conclusion

Autoimmune adrenalitis represents the most common cause of primary adrenal insufficiency in children beyond infancy, particularly in developed countries. Its clinical presentation is often insidious and nonspecific, leading to delayed diagnosis and increased risk of life-threatening adrenal crisis. A high index of suspicion, supported by biochemical evaluation and confirmation with ACTH stimulation testing and 21-hydroxylase autoantibody assays, is essential for early diagnosis. Recognition of associated autoimmune polyglandular syndromes is crucial, as timely screening and management of coexisting autoimmune disorders significantly improve long-term outcomes. Lifelong glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement therapy, combined with appropriate stress-dose education and regular follow-up, allows affected children to achieve normal growth, development, and quality of life. Ongoing advances in genetic diagnostics and evolving therapeutic strategies hold promise for earlier detection and more individualized management, emphasizing the need for continued awareness and multidisciplinary care in pediatric autoimmune Addison’s disease.

References

1. Bornstein SR, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol / PMC review. 2016/2015 summary.

2. Wolff ASB, et al. Autoimmune primary adrenal insufficiency. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2023.

3. Kilberg MJ. Adrenal Insufficiency in Children - Endotext (NCBI Bookshelf). 2024.

4. Pediatric adrenal insufficiency: challenges and solutions. D Nisticò et al. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 2022.

5. AIRE/APECED reviews and APS summaries — Huibregtse et al., De Martino et al., Paparella et al. (APS genetics).

6. Clinical guidance on adrenal crisis management — Endocrine Society / Endocrinology professional guidance pages.

7. Pediatric-specific practical guidance and recent reviews (2024–2025) on dosing and approach (Capalbo et al., Patti et al.).