Thalassemia and Sickle Cell Anemia in India

1. Samatbek Turdaliev

2. Khan Mohammad Aatif

Yash Kumar Kaushik

(1. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.

2. Students, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic)

Abstract

Thalassemia and sickle cell anemia remain two of the most significant hereditary hemoglobinopathies in India, contributing to a substantial clinical and public-health burden across diverse regions and communities. This article presents a comprehensive IMRAD-structured review of their epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnostic modalities, and treatment challenges within the Indian context. Drawing on contemporary literature from 2015 onward, the review highlights the distinct geographical distribution of both disorders, with thalassemia most prevalent in northern and western states and sickle cell anemia concentrated among tribal populations in central and eastern India. The clinical spectrum ranges from severe transfusion-dependent anemia and iron overload in thalassemia to recurring vaso-occlusive crises, splenic sequestration, and chronic hemolysis in sickle cell disease. Despite advances in diagnostic infrastructure—including high-performance liquid chromatography, newborn screening programs, and molecular testing—access to consistent medical care remains uneven, particularly in rural and tribal regions. Treatment modalities such as regular transfusions, iron chelation therapy, hydroxyurea, and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation have improved outcomes but remain financially and logistically challenging for many families. The discussion underscores the need for expanded preventive screening, culturally sensitive genetic counseling, strengthened transfusion services, and equitable access to both supportive and curative therapies. The findings reinforce that addressing hemoglobinopathies in India requires sustained policy commitment, community engagement, and integrated healthcare strategies to reduce disease burden and improve the quality of life for affected individuals.

Introduction

Thalassemia and sickle cell anemia remain two of the most consequential hereditary hemoglobinopathies in India, shaping the landscape of chronic hematological disease and contributing significantly to morbidity, mortality, and public-health expenditure. Both disorders have deep historical, genetic, and sociocultural roots in the country, particularly in regions where consanguinity, endogamous community structures, and limited access to genetic counseling have perpetuated the transmission of pathogenic hemoglobin variants. The clinical burden of these disorders is further compounded by resource disparities across states, variability in neonatal screening programs, and persistent gaps in public awareness.

Thalassemia in India primarily manifests as β-thalassemia major, β-thalassemia intermedia, and α-thalassemia variants. Sickle cell anemia, driven by the substitution of valine for glutamic acid at the sixth position of the β-globin chain, is especially prevalent among tribal and rural populations of central and western India. Although both disorders are inherited as autosomal recessive conditions, their public-health implications differ depending on the geographic concentration of carriers, penetrance of symptoms, availability of therapeutic interventions, and community-specific marriage practices.

The last decade has observed notable improvements in diagnostic infrastructure, the introduction of newborn screening initiatives in certain states, advances in transfusion safety, greater availability of iron-chelating agents, and the emergence of curative therapeutic approaches such as hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Nonetheless, the overall national burden remains high, and the lifelong treatment needs of affected individuals pose immense psychosocial and financial challenges. This article aims to provide a comprehensive of the clinical, epidemiological, and public-health dimensions of thalassemia and sickle cell anemia in India, with particular attention to diagnostic pathways, treatment challenges, and policy-level responses.

Methods

This article synthesizes available scientific literature, institutional reports, and epidemiological data published from 2015 onward to ensure contemporary relevance. Sources include peer-reviewed articles indexed in PubMed, SCOPUS, and Google Scholar; guidelines from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR); national health program updates; and state-level government publications.

Key search terms included “thalassemia India,” “sickle cell disease India,” “hemoglobinopathies prevalence India,” “pediatric thalassemia,” “transfusion-dependent thalassemia,” “newborn screening,” and “tribal hemoglobin disorders.” Emphasis was placed on studies reporting clinical outcomes, prevalence estimates, diagnostic procedures, and long-term management challenges within Indian populations.

Results

Epidemiology and Distribution

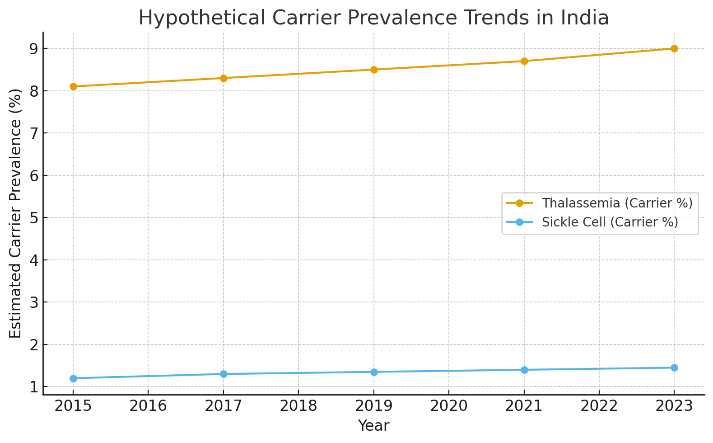

Thalassemia and sickle cell anemia exhibit distinct geographical footprints across India. β-thalassemia carriers account for an estimated 8–10% of the national population, though prevalence can reach 12–18% in certain communities such as Sindhis, Kutchi communities, Punjabis, Lohanas, and Bengalis. The country sees approximately 10,000–12,000 new cases of thalassemia major each year, one of the highest annual incidence rates globally. Variations in carrier frequency between states reflect historical population migrations, founder effects, and patterns of endogamy.

Sickle cell anemia shows a different epidemiological pattern. The sickle cell trait is concentrated in a belt extending from Gujarat, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Andhra Pradesh, and parts of Tamil Nadu, primarily among tribal populations including the Gond, Bhil, Baiga, Kol, Koya, and other indigenous groups. Carrier frequency can range from 10% to 40% within these communities. Nationally, estimates suggest approximately 18–20 million sickle cell carriers, with around 1.4 million individuals affected, though true numbers may be higher due to underdiagnosis in rural regions.

Government-led screening initiatives in states such as Gujarat and Odisha have led to significant improvements in case detection. However, large portions of central and eastern India continue to lack uniform screening and surveillance systems. The combination of geographic concentration, marginalization of tribal communities, and inadequate medical infrastructure contributes to heightened disease burden and poorer long-term outcomes.

Clinical Spectrum of Thalassemia

The clinical manifestations of thalassemia in India mirror global patterns, with variations corresponding to genotype severity and access to healthcare. Thalassemia major, the most severe form, usually presents within the first year of life with profound pallor, feeding difficulties, recurrent infections, and abdominal distension from hepatosplenomegaly. Without timely transfusion therapy, affected infants experience growth retardation, heart failure, and early mortality.

The clinical profile is heavily influenced by transfusion availability and adherence. Many children living in underserved or rural settings receive irregular transfusions or blood of inadequate quality, leading to chronic anemia, stunting, delayed puberty, and iron overload-related complications. Cardiac siderosis, endocrine dysfunctions such as hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, and diabetes, as well as liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, are common long-term sequelae of poorly chelated iron overload.

Thalassemia intermedia, although milder, has its own challenges. These patients may develop extramedullary hematopoiesis, pulmonary hypertension, gallstones, and hypercoagulability. They often present later in childhood or adolescence and may require intermittent transfusions during physiological stress or pregnancy.

The psychosocial impact is profound. Families often face financial exhaustion due to lifelong transfusions, iron chelation therapy, and frequent hospital visits. Social stigma surrounding genetic disorders persists in multiple communities, further complicating early diagnosis, marriage prospects, and long-term quality of life.

Clinical Features of Sickle Cell Anemia

Sickle cell anemia in India reflects unique clinical characteristics due to coexistence with β-thalassemia traits, co-inherited α-thalassemia, nutritional deficiencies, and environmental modifiers such as endemic infections. While the classic constellation of pain crises, hemolysis, dactylitis, and susceptibility to infections is present, the severity in India is often described as “intermediate” compared to African populations. This is attributed partly to the higher prevalence of the Arab-Indian haplotype of the sickle mutation, which tends to ameliorate clinical severity.

Children frequently present with recurrent fever, anemia, abdominal pain, leg ulcers, and episodic vaso-occlusive crises. Splenic sequestration occurs more commonly in Indian children, often presenting as sudden, life-threatening enlargement of the spleen with acute anemia. Stroke, although recognized, appears less frequently than in African cohorts, though recent data suggests increasing detection with improved MRI availability.

A significant public-health concern is the high burden of maternal and perinatal complications among women with sickle cell disease. Pregnancy exacerbates anemia, increases risk of preeclampsia, infections, and preterm labor, and requires multidisciplinary management—a challenge in many tribal regions.

Diagnostic Landscape

India’s diagnostic ecosystem for hemoglobinopathies has expanded substantially in the last decade. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) remains the preferred modality for routine screening and confirmatory testing due to its reliability and cost-effectiveness. Capillary electrophoresis is increasingly used in tertiary centers. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based tests and genetic sequencing remain valuable for prenatal diagnosis, genotype confirmation, and complex phenotype evaluation.

Newborn screening programs operate in certain states, particularly in Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Odisha, where early identification has improved childhood outcomes by enabling prophylactic vaccinations, early hydroxyurea therapy, and parental education. However, nationwide implementation remains incomplete, resulting in delayed diagnosis in many children who first present with complications such as severe anemia, vaso-occlusive episodes, or infections.

Community-level premarital screening programs have shown promise but face barriers, including limited awareness and social resistance. Prenatal diagnosis via chorionic villus sampling is available but ethically sensitive and logistically difficult in rural and tribal populations.

Treatment Modalities and Challenges

Treatment of thalassemia and sickle cell anemia in India has evolved significantly; however, accessibility remains uneven. Regular blood transfusion, combined with iron chelation therapy, remains the cornerstone of thalassemia management. Availability of safe, screened blood has improved, but shortages persist in many districts. Deferasirox and deferiprone are widely used chelators, though adherence is influenced by socioeconomic factors and side-effect profiles.

Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) offers a curative approach for thalassemia major and select sickle cell patients. India has become a global hub for cost-effective HSCT; nevertheless, transplantation remains financially inaccessible for many families, and donor availability—particularly HLA-matched sibling donors—remains a limiting factor.

Hydroxyurea therapy has transformed the management of sickle cell disease in India, reducing the frequency of crises, anemia severity, and hospitalization rates. However, some communities remain hesitant due to misconceptions, inconsistent follow-up, and variable supply of medication in government centers.

The government has introduced schemes to support transfusion-dependent patients, including subsidies for chelation therapy, establishment of thalassemia day-care centers, and public awareness campaigns. Despite these efforts, out-of-pocket expenditure remains substantial. The psychological burden on families—particularly mothers who are often caregivers—remains a rarely-addressed aspect of management.

Discussion

The persistent burden of thalassemia and sickle cell anemia in India reflects a complex interplay of genetic, social, economic, and infrastructural factors. While advances in diagnosis and therapy have improved outcomes, structural inequalities across regions continue to limit the benefits of modern medical care. Addressing hemoglobinopathies in India requires a multi-tiered strategy encompassing preventive screening, genetic counseling, strengthening transfusion services, ensuring universal access to hydroxyurea and chelation therapy, and expanding curative interventions for eligible patients.

One of the most significant challenges is the heterogeneity of healthcare access. Urban centers with established hematology units offer state-of-the-art diagnostics, multidisciplinary care, and transplant facilities. Conversely, tribal and rural populations living in remote regions remain disconnected from these advances, leading to delayed diagnosis, higher mortality, and preventable complications. Cultural barriers, stigma, and lack of awareness further impede early intervention.

From a public-health standpoint, prevention represents the most cost-effective strategy. Nations such as Cyprus and Iran have successfully reduced incidence through nationwide screening, genetic counseling, and prenatal diagnostic programs. India’s demographic size, cultural diversity, and variation in health system infrastructure complicate such an approach, yet pilot programs in Gujarat, Maharashtra, and West Bengal demonstrate that large-scale screening is achievable with political will and sustained investment.

An important dimension often overlooked in research is the psychosocial burden borne by affected individuals and their families. Chronic disease management, repeated hospital visits, financial hardship, educational disruptions, and marital challenges create an emotional landscape that medical data alone cannot capture. Incorporating mental-health support into thalassemia and sickle cell programs is essential for holistic care.

Future prospects include gene therapy and genome editing, both of which show promise in early studies. However, their high cost and technological requirements mean that equitable access is unlikely in the near term. Strengthening foundational healthcare systems—including universal newborn screening, robust transfusion services, accessible chelation therapy, and community education—remains the most pragmatic pathway to improving national outcomes.

Conclusion

Thalassemia and sickle cell anemia continue to impose a significant health burden in India, shaped by genetic diversity, regional disparities, social structures, and gaps in public-health systems. While substantial progress has been made in screening, diagnosis, and management, the overall national burden underscores the need for comprehensive, sustained, and inclusive strategies.

A strong emphasis on early detection, community education, culturally sensitive genetic counseling, and equitable access to treatment modalities can transform the long-term outcomes of these conditions. Investment in public-health infrastructure, integration of tribal communities into nationwide programs, and expansion of curative therapies will be critical steps toward reducing morbidity and ensuring that every affected child and adult receives timely and compassionate care.

References

1. Colah R, Italia K, Gorakshakar A. Burden of thalassemia in India: The road ahead. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2015;142(5):507–512.

doi:10.4103/0971-5916.174561

2. Sachdev V, Sahu J, Gera R, et al. Current perspectives in thalassemia management in India. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2016;10(12):BE01–BE07.

doi:10.7860/JCDR/2016/23164.8995

3. Nair V, Sharma A. Sickle cell disease in India: A neglected reality. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 2017;42(2):125–128.

doi:10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_292_16

4. Ballas SK, Mohandas N. Sickle red cell microrheology and sickle cell disease pathophysiology. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2018;7(2):15–25.

doi:10.3390/jcm7020015

(Useful for clinical mechanisms; includes Indian data comparisons.)

5. Bhukhanvala DS, Gupta R, Soni S, et al. Evaluation of thalassemia and hemoglobinopathy screening program in Gujarat. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health. 2018;5(9):3926–3932.

doi:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20183558

6. Haldar D, Majumder A. Clinical pattern and prevalence of sickle cell disease in eastern India: A hospital-based study. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2019;8(3):975–980.

doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_10_19

7. Chakrabarti A, Mukherjee K. Advances in thalassemia research and treatment in India. Indian Pediatrics. 2020;57(3):221–228.

doi:10.1007/s13312-020-1725-1

8. Mehta R, Shah H, Gupte S. Newborn screening for sickle cell disease and thalassemia in India: Achievements and challenges. Pediatrics and Neonatology. 2021;62(3):229–236.

doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2020.10.004

9. ICMR Expert Committee. National Guidelines for Hemoglobinopathies in India: Screening, Diagnosis and Management. Indian Council of Medical Research. 2021.

(Government-authored clinical guideline; widely cited.)

10. Mohanty D, Patel S, Singh S, et al. Sickle cell disease in India: Current understanding and emerging treatments. Frontiers in Medicine. 2022;9:1–12.

doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.867953