Thymic Disorders in Children: A Comparative Review of India and Kyrgyzstan

1. Ritesh Jaiswal

2. Shakeel Ahmed

3. Narmatova Elmira Baltabaevna

(1. Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic

2. Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.

3. Lecturer, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.)

Abstract

The thymus is a primary lymphoid organ essential for the development, maturation, and selection of T lymphocytes, playing a pivotal role in establishing adaptive immunity during childhood. Disorders of the thymus in the pediatric population can result in significant immunological dysfunction, predisposing affected children to recurrent infections, autoimmune phenomena, and increased morbidity and mortality. This narrative review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of thymic disorders among children, with a particular focus on India and Kyrgyzstan, representing South Asian and Central Asian healthcare contexts respectively.

The review synthesizes available literature on congenital and acquired thymic disorders, including thymic aplasia or hypoplasia (notably DiGeorge syndrome), thymic tumors, thymic cysts, and secondary thymic involvement in systemic diseases. Differences in epidemiology, diagnostic capabilities, healthcare infrastructure, and management strategies between India and Kyrgyzstan are explored. Special emphasis is placed on the impact of socioeconomic factors, nutritional status, infectious disease burden, and access to specialized pediatric immunology services.

This comparative analysis highlights the likelihood of underdiagnosis of thymic disorders in both countries, particularly in resource-limited settings, and underscores the need for increased clinical awareness, improved diagnostic pathways, and collaborative regional research. Strengthening early recognition and multidisciplinary management of thymic disorders has the potential to significantly improve immunological health and long-term outcomes in affected children across diverse healthcare systems.

Keywords: Thymus disorders, Pediatric immunology, DiGeorge syndrome, Thymic hypoplasia, India, Kyrgyzstan, Immunodeficiency, Children

Introduction

The thymus is a bilobed lymphoepithelial organ located in the anterior mediastinum and is most active during fetal life and early childhood. It serves as the primary site for T-cell maturation, differentiation, and central tolerance, processes that are fundamental to the development of a functional and self-tolerant immune system. Any structural or functional abnormality of the thymus during childhood may lead to varying degrees of immunodeficiency, altered immune regulation, and susceptibility to infections and autoimmune diseases.

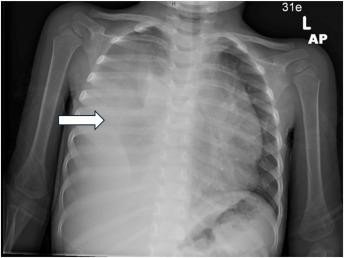

Figure: Paediatric Thymus

Pediatric thymic disorders encompass a broad spectrum of conditions, ranging from congenital developmental anomalies such as thymic aplasia or hypoplasia to acquired disorders including tumors, cysts, and secondary thymic atrophy associated with systemic diseases. While some thymic abnormalities are rare, others may be more prevalent but remain underrecognized due to nonspecific clinical presentations and limited access to advanced diagnostic tools.

India, with its vast population and heterogeneous healthcare infrastructure, faces unique challenges in identifying and managing pediatric thymic disorders. High birth rates, variable nutritional status, and a significant burden of infectious diseases influence thymic health and immune development. Kyrgyzstan, a Central Asian country with a smaller population, presents a different yet equally important context, characterized by limited specialized pediatric services, geographic barriers to healthcare access, and a dual burden of infectious and non-communicable diseases.

Despite these differences, both countries share common challenges, including underdiagnosis of rare immunological disorders, scarcity of pediatric immunologists, and limited availability of genetic testing. This review aims to synthesize existing knowledge on thymic disorders in children, compare the clinical landscape in India and Kyrgyzstan, and identify gaps in research and healthcare delivery that warrant further attention.

Methodology

This narrative review was conducted using a systematic and structured approach to identify relevant literature addressing thymic disorders in children, with emphasis on data from India and Kyrgyzstan.

Literature Search Strategy

An extensive literature search was performed using electronic databases including PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms were combined using Boolean operators and included terms such as thymus, thymic disorders, children, pediatric immunodeficiency, DiGeorge syndrome, India, Central Asia, and Kyrgyzstan.

Given the limited volume of country-specific publications from Kyrgyzstan, regional Central Asian studies and data from comparable healthcare settings were also reviewed to contextualize findings. Reference lists of relevant articles and review papers were manually screened to identify additional sources.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they:

● Focused on thymic disorders in children aged 0–18 years

● Reported clinical, diagnostic, or management data relevant to India or Kyrgyzstan

● Included original research, case reports, case series, or review articles

● Were published in English

Studies were excluded if they:

● Focused exclusively on adult populations

● Addressed thymic physiology without discussing pathological conditions

● Were preclinical without clinical correlation

● Lacked relevance to pediatric populations

Due to heterogeneity in study designs and outcomes, a formal meta-analysis was not feasible. Instead, a narrative synthesis approach was adopted to summarize and interpret findings.

Results

Congenital Thymic Disorders: DiGeorge Syndrome (Thymic Aplasia and Hypoplasia)

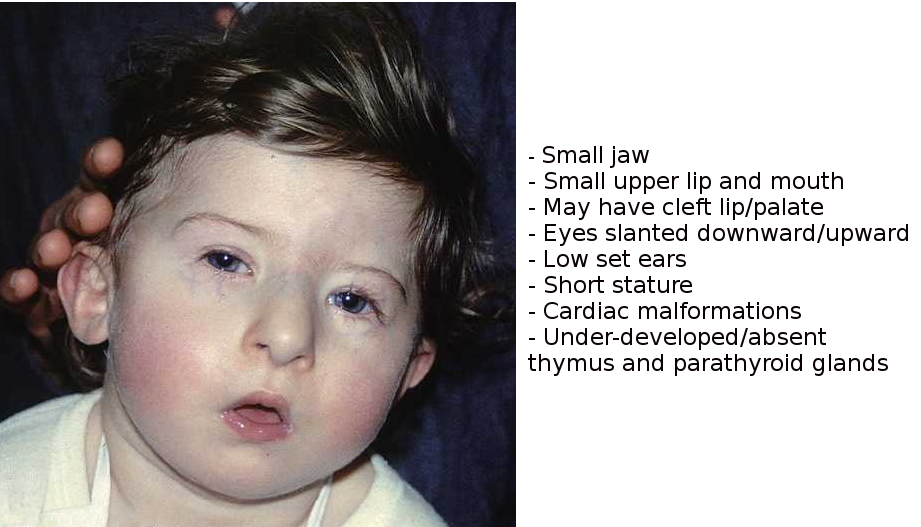

DiGeorge syndrome (DGS), also known as 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, is the most well-recognized congenital thymic disorder in children. It results from abnormal development of the third and fourth pharyngeal pouches, leading to thymic hypoplasia or aplasia, parathyroid dysfunction, and congenital cardiac anomalies.

India

In India, the exact prevalence of DGS remains uncertain due to the absence of national screening programs and limited access to genetic testing. However, studies conducted in tertiary care centers suggest that DGS is underdiagnosed, particularly among children presenting with congenital heart disease and hypocalcemic seizures. Immunodeficiency in Indian children with DGS varies widely, ranging from mild susceptibility to infections to severe combined immunodeficiency-like presentations in cases of complete thymic aplasia.

Kyrgyzstan

In Kyrgyzstan, published data on DGS are extremely limited. Diagnosis is often based on clinical features rather than genetic confirmation, due to restricted availability of molecular diagnostic facilities such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or MLPA. Children with congenital heart defects, recurrent infections, and growth failure may not be systematically evaluated for underlying thymic or genetic abnormalities. As a result, many cases likely remain undiagnosed or misclassified as nonspecific immunodeficiency or malnutrition-related immune suppression.

In both countries, delayed diagnosis contributes to increased morbidity, particularly from recurrent respiratory and opportunistic infections.

Thymic Tumors in Children

Thymomas and thymic carcinomas are rare in the pediatric population worldwide. When they do occur, they often present as anterior mediastinal masses and may be associated with autoimmune conditions.

India

Pediatric thymomas in India are reported predominantly as isolated case reports or small case series. Clinical presentation commonly includes cough, chest pain, dyspnea, or incidental findings on chest imaging. Associations with autoimmune disorders such as myasthenia gravis are rare but have been documented. Surgical resection remains the cornerstone of management, with adjuvant therapy reserved for invasive or malignant cases.

Kyrgyzstan

In Kyrgyzstan, thymic tumors in children are exceedingly rare, and most cases are managed at tertiary centers in the capital or referred abroad. Limited access to advanced imaging modalities and pediatric thoracic surgery may delay diagnosis and treatment. Consequently, reported incidence likely underrepresents the true disease burden.

Thymic Cysts

Thymic cysts are benign, fluid-filled lesions that may be congenital or acquired. They are frequently asymptomatic and detected incidentally.

In both India and Kyrgyzstan, thymic cysts are often identified during imaging for unrelated respiratory symptoms. Large cysts may cause compressive symptoms, including cough and dyspnea. Conservative management is appropriate for asymptomatic cases, while surgical excision is recommended for symptomatic or infected cysts.

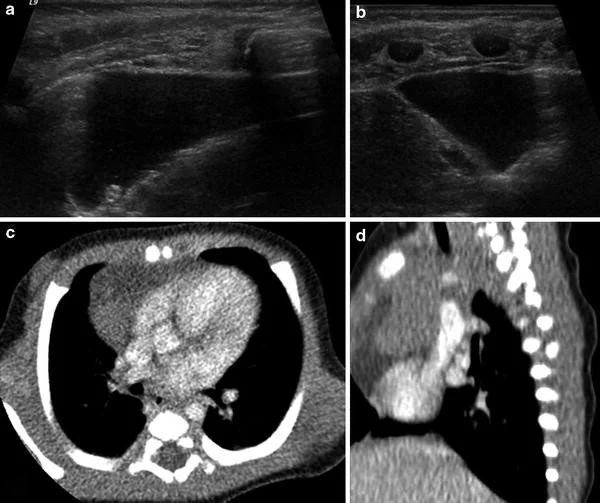

Figure: Thymic Hyperplasia

Secondary Thymic Involvement in Systemic Diseases

The thymus is highly sensitive to systemic stressors, particularly in children.

Malnutrition

In India, protein-energy malnutrition remains a significant public health issue and is strongly associated with thymic atrophy. Reduced thymic size correlates with impaired T-cell production and increased susceptibility to infections.

In Kyrgyzstan, although severe malnutrition is less prevalent, micronutrient deficiencies and childhood anemia may contribute to suboptimal thymic function, particularly in rural areas.

Infections

Chronic infections such as tuberculosis and HIV can directly or indirectly affect thymic architecture and function. India bears a high burden of pediatric tuberculosis and HIV, both of which are associated with thymic involution. Kyrgyzstan also faces challenges related to tuberculosis, particularly multidrug-resistant strains, which may have implications for immune development in children.

Discussion

This comparative review highlights both shared and unique challenges in the recognition and management of pediatric thymic disorders in India and Kyrgyzstan. In both settings, congenital thymic disorders such as DiGeorge syndrome are likely underdiagnosed due to limited awareness, lack of routine genetic screening, and overlap with more common pediatric conditions.

India benefits from a relatively larger number of tertiary care centers and specialized pediatric services, yet disparities persist between urban and rural regions. Kyrgyzstan, while having a smaller population, faces challenges related to limited subspecialty care and diagnostic infrastructure, particularly outside major cities.

Secondary thymic involvement due to malnutrition and infections represents a preventable contributor to immunodeficiency in both countries. Addressing these underlying determinants is essential for improving pediatric immune health.

Conclusion

Thymic disorders in children represent an important yet underrecognized cause of immunodeficiency and morbidity in both India and Kyrgyzstan. Congenital conditions such as DiGeorge syndrome, rare thymic tumors, thymic cysts, and secondary thymic dysfunction due to systemic illnesses collectively contribute to immune compromise during critical periods of growth and development.

Improved clinical awareness, early recognition, and strengthened diagnostic pathways are urgently needed. Expanding access to genetic testing, pediatric immunology services, and multidisciplinary care will be essential in both countries. Collaborative regional research and the development of context-specific clinical guidelines may further enhance outcomes for affected children.

References

Guleria P, Husain N, Shukla S, Jain D, Mathur SR, Iyer VK. PD-L1 immuno-expression assay in thymomas: Study of 84 cases and review of literature. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018;34:135-141. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2018.03.012.

Ocal T, Turken A, Ciftci AO, Senocak ME, Buyukpamukcu N. Thymic enlargement in childhood. Turk J Pediatr. 2000;42(4):298-303.

Yaris N, Nas Y, Cobanoglu U, Guler E, Kocak H. Thymic carcinoma in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47(2):224-227. doi:10.1002/pbc.20468.

Dhall G, Ginsburg HB, Bodenstein L, et al. Thymoma in children: Report of two cases and review of literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;26(10):681-685. doi:10.1097/01.mph.0000141069.38462.d8.

Carretto E, Inserra A, Ferrari A, et al. Epithelial thymic tumours in paediatric age: A report from the TREP project. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:28. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-6-28.

Manchanda S, Bhalla AS, Jana M, Gupta AK. Imaging of the pediatric thymus: Clinicoradiologic approach. World J Clin Pediatr. 2017;6(1):10-23. doi:10.5409/wjcp.v6.i1.10.

McDonald-McGinn DM, Sullivan KE, Marino B, et al. 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15071. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2015.71.

Sullivan KE. Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: DiGeorge syndrome/velocardiofacial syndrome. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008;28(2):353-366. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2008.01.003.

Savino W. The thymus gland is a target in malnutrition. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56(Suppl 3):S46-S49. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601480.

Chinn IK, Shearer WT. Severe combined immunodeficiency disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2015;35(4):671-694. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2015.07.004.

Haynes BF, Markert ML, Sempowski GD, Patel DD, Hale LP. The role of the thymus in immune reconstitution in HIV infection. Immunol Res. 2000;22(2-3):233-248. doi:10.1385/IR:22:2-3:233.

World Health Organization. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: Report of a WHO scientific group. Geneva: WHO; 1997.