Tubulointerstitial Nephritis

1. Samatbek Turdaliev

2. Sumit Kanthale

Arundhathi Shaji

(1. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic

2. Students, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.)

Abstract

Tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN) is a group of renal disorders characterized by predominant inflammation and injury of the renal tubules and interstitial tissue, with relative preservation of glomerular structures in the early stages. It represents an important and potentially reversible cause of acute kidney injury (AKI) and a significant contributor to chronic kidney disease (CKD) worldwide.

Emerging biomarkers offer promising non-invasive tools for diagnosing ATIN and differentiating it from other causes of AKI and acute kidney disease. Biomarker applications, as an alternative, are viewed through the lens of distinct immune reaction subtypes, including variations in type IV hypersensitivity mechanisms. Biomarkers such as urinary CXC chemokine ligand (CXCL)9 and cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-9 reflect T-cell polarization and specific inflammatory pathways, shedding light on T helper (Th)1- and Th2-mediated immune responses. Among these, the urinary CXCL9-to-creatinine ratio demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity, with well-defined thresholds guiding clinical decisions. Urinary retinol-binding protein and serum C-reactive protein (CRP) have also been explored, particularly in immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICPI)-associated AKI. However, their non-specificity and overlap with other AKI etiologies limit their utility in isolating ATIN-specific pathways.

Drug-induced hypersensitivity reactions are the most common etiology, particularly associated with antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). The clinical presentation is often nonspecific, leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment. Early recognition and timely withdrawal of the offending agent, along with appropriate therapeutic intervention, can significantly improve renal outcomes. [1,2]

Keywords: Tubulointerstitial nephritis, Acute interstitial nephritis, Drug-induced nephropathy, Renal tubular dysfunction, Chronic kidney disease

Introduction

Tubulointerstitial nephritis refers to a heterogeneous group of renal diseases in which the primary pathological process involves the renal tubules and surrounding interstitial tissue rather than the glomeruli or renal vasculature. Despite minimal early glomerular involvement, tubulointerstitial damage significantly impairs key renal functions, including urine concentration, electrolyte balance, and acid–base homeostasis. Tubulointerstitial nephritis accounts for approximately 10–15% of intrinsic causes of acute kidney injury and is frequently underdiagnosed due to its nonspecific clinical presentation. Early diagnosis is crucial, as prompt treatment can prevent progression to chronic kidney disease. [1,3]

Etiology

The etiology of tubulointerstitial nephritis is diverse and includes drug-induced, infectious, autoimmune, metabolic, toxic, and obstructive causes. Drug-induced acute tubulointerstitial nephritis is the most common form and usually results from an immune-mediated hypersensitivity reaction rather than direct nephrotoxicity.

Drug-Induced ATIN

Since the 1950s, the widespread use of drugs has increased rapidly, significantly altering the etiology of ATIN, and this trend is expected to continue. In a single-center study conducted between 1993 and 2011, antibiotics were responsible for 49% of biopsy-confirmed ATIN cases, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for 14%, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for 11% Among the most frequently detected drugs were omeprazole (12%), amoxicillin (8%), and ciprofloxacin (8%). In another study, medications accounted for 71% of ATIN cases, with 35% related to antibiotics, 35% to PPIs, 20% to NSAIDs, and 10% to other drugs.

Trends in drug use, geographic differences, and changes in medical practices can alter the distribution of drug-induced ATIN over time. For example, the widespread use of newly developed drugs or a better understanding of the side-effect profiles of existing medications may bring different drug classes into prominence in the future. ICPIs (8 agents target the PD-1/PD-L1 signalling pathway or the CTLA-4 pathway) are a typical example of this shift. Although these drugs enhance the immune system’s attack on cancer by preventing cancer cells from evading T cells, they also cause nonspecific immune disinhibition, resulting in frequent and sometimes severe adverse events (59%–85%). ATIN associated with ICPIs typically develops approximately 14 weeks (range: 6–37 weeks) after the initiation of treatment. In 69% of these cases, patients are also using other potentially nephrotoxic drugs. ATIN is identified as the cause of AKI in 83% of the 151 biopsied cases among 429 patients with ICPI-AKI.14,15 Following therapy, most patients (64%) show clinical improvement with either complete or partial renal recovery, although mild kidney impairment persists at 12 months.

Infection-Related ATIN

Microorganisms can lead to ATIN by directly infecting renal parenchyma, causing acute pyelonephritis, or more commonly, by triggering an immune response in the tubulointerstitium. A wide variety of bacteria, viruses, parasites, mycoplasma, and chlamydia are associated with ATIN. Infections often present with systemic symptoms, making it difficult to distinguish between the effects of the infection itself and the immune response. In addition, the antibiotics used to treat these infections can also contribute to ATIN.

AKI is commonly observed in infections such as COVID-19, HIV, leptospirosis, and hantavirus. Hantavirus, a zoonotic disease transmitted by rodents, can cause severe back pain, thrombocytopenia, and nephrotic-range proteinuria. In biopsy specimens from hantavirus-related ATIN cases, interstitial inflammation, congestion, and hemorrhage may be detected.2 Higher viral loads may contribute to infection-related ATIN, as suggested by studies on HIV and COVID-19. In HIV-infected patients, chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis was among the histologic findings, with higher viral loads, diabetes mellitus, and older age being risk factors for kidney disease, indicating a potential link between viral replication and renal outcomes. In COVID-19, a higher SARS-CoV-2 viral load in urine sediment correlated with increased AKI incidence and higher mortality, supporting the idea that viral load may influence kidney injury severity. The spectrum of HIV-related kidney injury is particularly complex, involving direct viral effects, immune-mediated damage, drug toxicity, and contributions from opportunistic infections and comorbidities.

Common offending drugs include beta-lactam antibiotics, sulfonamides, rifampicin, NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors, and diuretics. Infectious causes include bacterial, viral, and mycobacterial infections, with renal tuberculosis remaining important in endemic regions. Autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, sarcoidosis, and IgG4-related disease are well-recognized causes. Chronic exposure to analgesics, heavy metals, metabolic abnormalities such as hypercalcemia, and prolonged urinary tract obstruction may lead to chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis. [1,4,5]

Pathophysiology

Tubulointerstitial nephritis is primarily an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder. The offending antigen triggers a cell-mediated immune response with infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and occasionally eosinophils into the renal interstitium.

Delayed-Type Cellular Hypersensitivity and Phenotypic Evolution of the Immune Response

In type 4 hypersensitivity, antigen exposure activates immune cells (e.g., epithelial cells, innate lymphoid cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and T cells), leading to inflammation. Depending on antigenic stimulation, this response may evolve into chronic phenotypes, potentially resulting in fibrosis and permanent damage.

Type 4 hypersensitivity is subclassified into type 4a, 4b, and 4c reactions, driven by specific T cells, mediators, and cellular interactions. The pharmacologic interaction with immune receptors concept describes how certain drugs can directly activate T cells through reversible binding to T-cell receptors or human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules, contributing to ATIN pathogenesis.

This inflammatory response causes tubular epithelial injury, interstitial edema, and impaired tubular transport. If inflammation persists, fibroblast activation and extracellular matrix deposition result in interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. Progressive nephron loss ultimately leads to irreversible chronic kidney disease. [2,6]

Clinical Features

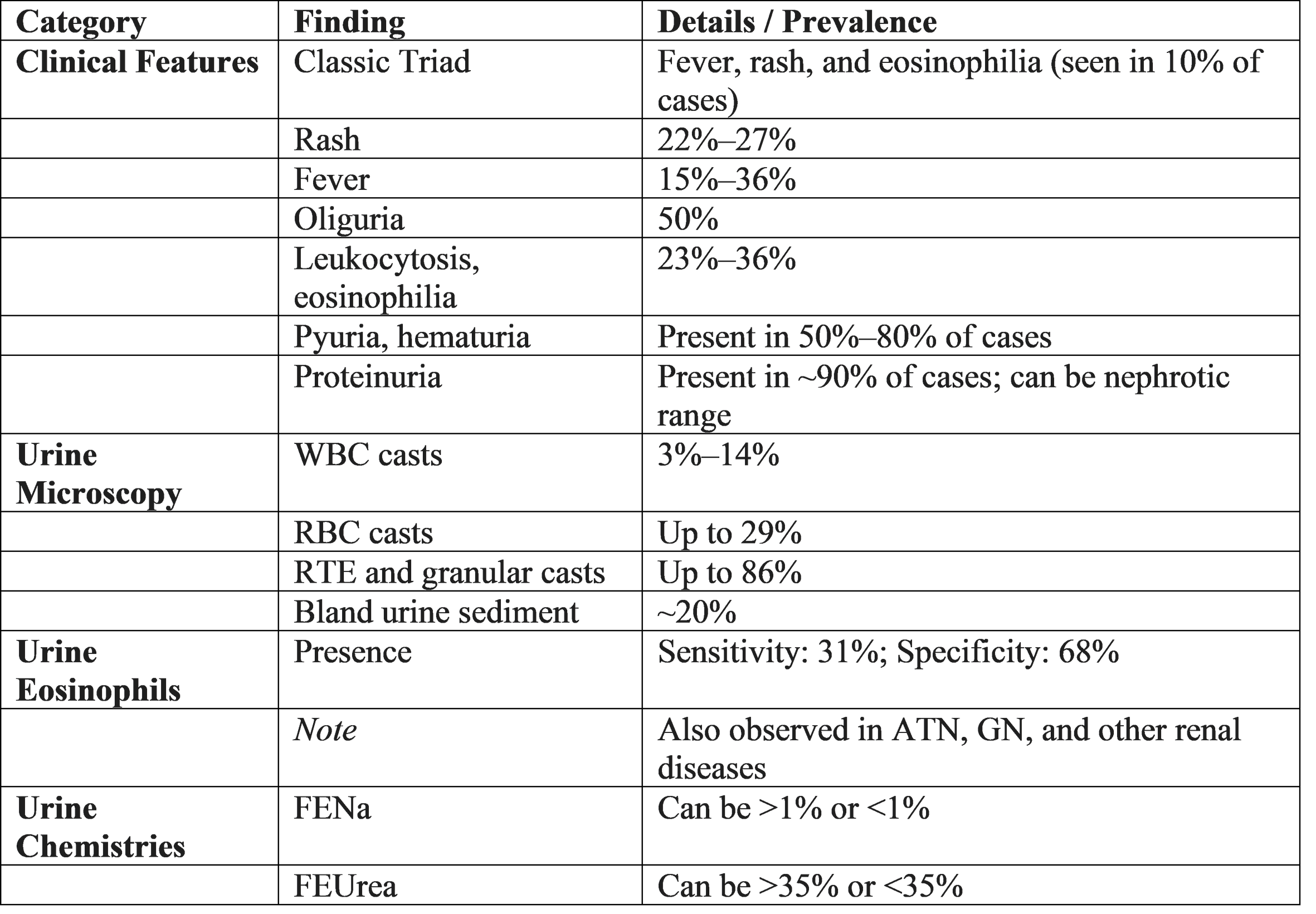

Clinical manifestations vary depending on whether the disease is acute or chronic. Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis commonly presents with acute kidney injury and a rapid rise in serum creatinine. Patients may experience oliguria or polyuria due to impaired concentrating ability.

The classical triad of fever, rash, and eosinophilia is suggestive but occurs in a minority of patients. Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis presents insidiously with fatigue, polyuria, nocturia, polydipsia, and gradual decline in renal function. Anemia and features of chronic kidney disease appear in advanced stages. [1,4,7,11]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion, particularly in patients with unexplained acute kidney injury. Laboratory investigations typically reveal elevated serum creatinine and urea.

Urinalysis shows sterile pyuria, mild proteinuria, white blood cell casts, and sometimes eosinophiluria. Urine analysis and urine culture are indicated if UTI is suspected, and blood cultures should be collected in case of severe systemic symptoms. In case of UTI, the urine dipstick is usually positive for nitrites, blood, protein, and leukocyte esterase, and the urine microscopy typically shows pyuria, defined by more than 10 white blood cells per milliliter (WBC/mL). Since the presence of pyuria alone cannot be used to diagnose a UTI, other different diagnoses should be considered in its absence. However, less than 10 WBC/mL in the urine may be indicative of a UTI if typical symptoms or a consistent clinical context are present. Bacteriuria is confirmed by a urine culture and allows for the determination of antibiotic sensitivity in order to direct the treatment, even retrospectively if the antibiotic has been started empirically. Bacteriuria is defined as the presence of bacterial growth in urine and is considered significant when it meets the standard quantitative criterion of greater than 10⁵ CFU/mL, in order to rule out contamination of the sample. However, this criterion varies according to the form of clinical presentation, 10³ CFU/mL for cystitis and 10⁴ CFU/mL for acute pyelonephritis or complicated UTIs are considered also significant growth. It should be noted that the low CFU/mL in cystitis are mainly limited to E. coli ,whereas not all organisms found in urine cultures are pathogens such as, Staphyloccus epidermadis (except in the presence of ureteral stents),lactobacillus and Guardenella vaginalis The urine can be contaminated during the collection of the sample by bacteria that colonize the distal urethra and genital mucosa, so it is recommended to clean the urinary meatus beforehand, collect the urine sample midstream in a sterile container, and in case it is not taken immediately to the laboratory, store in a refrigerator to avoid bacterial overgrowth. For the diagnosis of UTI, the sample must be collected before starting the antibiotic treatment and straight catheterization to obtain a urine specimen can be considered as an alternative.

Tubular dysfunction leads to electrolyte disturbances such as metabolic acidosis, hypokalemia, or hyponatremia. Renal ultrasonography may reveal normal or enlarged kidneys in acute disease and small kidneys in chronic disease. Renal biopsy remains the gold standard, demonstrating interstitial inflammation, tubulitis, and fibrosis depending on disease chronicity. [1,3,8]

Treatment

Immediate withdrawal of the offending agent is the most important step in management. Supportive therapy includes maintaining adequate hydration and correcting electrolyte abnormalities.

Corticosteroids are beneficial in accelerating renal recovery, particularly when initiated early in biopsy-proven acute tubulointerstitial nephritis or when renal function fails to improve with conservative management Corticosteroids remain the cornerstone of ATIN treatment, typically initiated with oral prednisolone or prednisone at 60 mg/d or 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/d. In drug-induced ATIN, treatment duration generally ranges from 7 to 10 days to a maximum of 6 to 8 weeks, with a tailored tapering strategy. A multicenter retrospective study by Fernandez-Juárez et al found no benefit to extending corticosteroid therapy beyond 8 weeks. An exception exists for ICPI-associated ATIN, where treatment may extend to 3 to 6 months. Shorter regimens have also shown benefit in ICPI-associated ATIN, highlighting the need for individualized treatment durations.

In severe AKI cases, i.v. pulse steroids can be administered, though no significant advantage over oral high-dose regimens has been demonstrated. Treatment planning should account for patient factors such as age, frailty, comorbidities, and potential side effects of glucocorticoids, especially in older patients with increased risks of infections, osteoporosis, diabetes, thromboembolic events, and hypertension.

Treatment of underlying infections, autoimmune diseases, or obstruction is essential. Management of chronic disease focuses on slowing progression and treating complications of chronic kidney disease. [1,5,9]

Clinical Recommendations

All patients with unexplained acute kidney injury should undergo a detailed drug history and evaluation for tubulointerstitial nephritis. Early diagnosis and treatment significantly improve prognosis. Renal biopsy should be considered when the diagnosis is uncertain or renal function deteriorates rapidly. Rational prescribing practices and avoidance of unnecessary nephrotoxic agents are crucial preventive measures. Long-term follow-up is recommended to assess renal recovery and progression to chronic kidney disease. [3,9,10]

Conclusion

Tubulointerstitial nephritis is a clinically important and potentially reversible renal disorder. Delay in diagnosis may lead to irreversible renal damage and chronic kidney disease. Increased awareness, early recognition, and evidence-based management are essential to improving patient outcomes. [1,2]

References

1. Acute Interstitial Nephritis – StatPearls – NCBI https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482323/

2. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 22nd Edition – Tubulointerstitial Diseases https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com

3. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury https://kdigo.org/guidelines/acute-kidney-injury/

4. Chronic Tubulointerstitial Nephritis – MSD Manual Professional Edition https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/genitourinary-disorders/tubulointerstitial-diseases

5. Drug-Induced Acute Interstitial Nephritis – Kidney International https://www.kidney-international.org/article/S0085-2538(15)55213-4/fulltext

6. Neilson EG. Pathogenesis and therapy of interstitial nephritis – Kidney International https://www.kidney-international.org/article/S0085-2538(15)47624-5/fulltext

7. Acute Interstitial Nephritis: Clinical Features and Response to Corticosteroids – NDT https://academic.oup.com/ndt/article/19/11/2778/1844169

8. Chronic Tubulointerstitial Disease – American Journal of Kidney Diseases https://www.ajkd.org/article/S0272-6386(96)90078-2/fulltext

9. Early Steroid Treatment Improves Renal Recovery – Kidney International https://www.kidney-international.org/article/S0085-2538(15)55322-2/fulltext

10. Drug-Induced Acute Interstitial Nephritis – Nature Reviews Nephrology https://www.nature.com/articles/nrneph.2010.2

11. T. Sahutoglu. Update on acute tubulointerstitial nephritis: clinical characteristics and management. Kidney International Reports. 2025; (article S2468-0249(25)00193-7). Available from: https://www.kireports.org/action/showFullTableHTML?isHtml=true&tableId=tbl4&pii=S2468-0249%2825%2900193-7