Amenorrhea: Pathophysiology, Diagnostic Paradigms, and Management

1. Aidarbek kyzy Aidanek

2. Ankit Mishra

Bhupesh Kumar

Bedprakash Patel

(1. Instructor of department of Obstetrics, gynecology and surgical disciplines, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyzstan.

(2. Students, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyzstan)

Abstract

Amenorrhea, the absence of menstrual menses, is a common clinical symptom that serves as a vital sign of female reproductive and systemic health. It is broadly categorized into primary amenorrhea (failure of menarche) and secondary amenorrhea (cessation of established menses). This review synthesizes current evidence regarding the diverse etiologies affecting the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, including functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA), polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and primary ovarian insufficiency (POI). We discuss updated diagnostic algorithms that prioritize the exclusion of pregnancy followed by systematic hormonal and imaging evaluations. Special attention is given to the 2023 international guidelines for PCOS and the long-term skeletal and cardiovascular consequences of chronic hypoestrogenism. Management strategies emphasize a multidisciplinary approach focused on correcting energy imbalances, hormonal replacement, and treating underlying structural or endocrine disorders.

Keywords: Primary Amenorrhea, Secondary Amenorrhea, Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, Primary Ovarian Insufficiency, Bone Mineral Density, HPO Axis.

1. Introduction and Definitions

Amenorrhea is not a diagnosis in itself but a symptom of an underlying anatomical, genetic, or neuroendocrine abnormality.1 It is categorized based on the timing of menses cessation and the presence or absence of prior menstrual cycles.

1.1 Primary Amenorrhea

Primary amenorrhea is defined as the failure of menarche to occur by age 15 in individuals with normal growth and secondary sexual characteristics.2 Evaluation is also indicated if a girl reaches age 13 without any signs of puberty, such as breast development (thelarche). This earlier threshold is critical because the absence of secondary sexual characteristics often suggests a global delay in pubertal development or significant genetic abnormalities.

1.2 Secondary Amenorrhea

Secondary amenorrhea is the absence of menses for three consecutive months in those who previously had regular cycles, or for six months in those with a history of irregular menses.4 It is estimated that approximately 1 in 4 women who are not pregnant, breastfeeding, or menopausal will experience amenorrhea at some point in their lives.6

2. Etiology and Pathophysiology

The "menstrual pathway" requires the functional integrity of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, ovaries, and the genital outflow tract. Disruption at any level results in amenorrhea.

2.1 Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea (FHA)

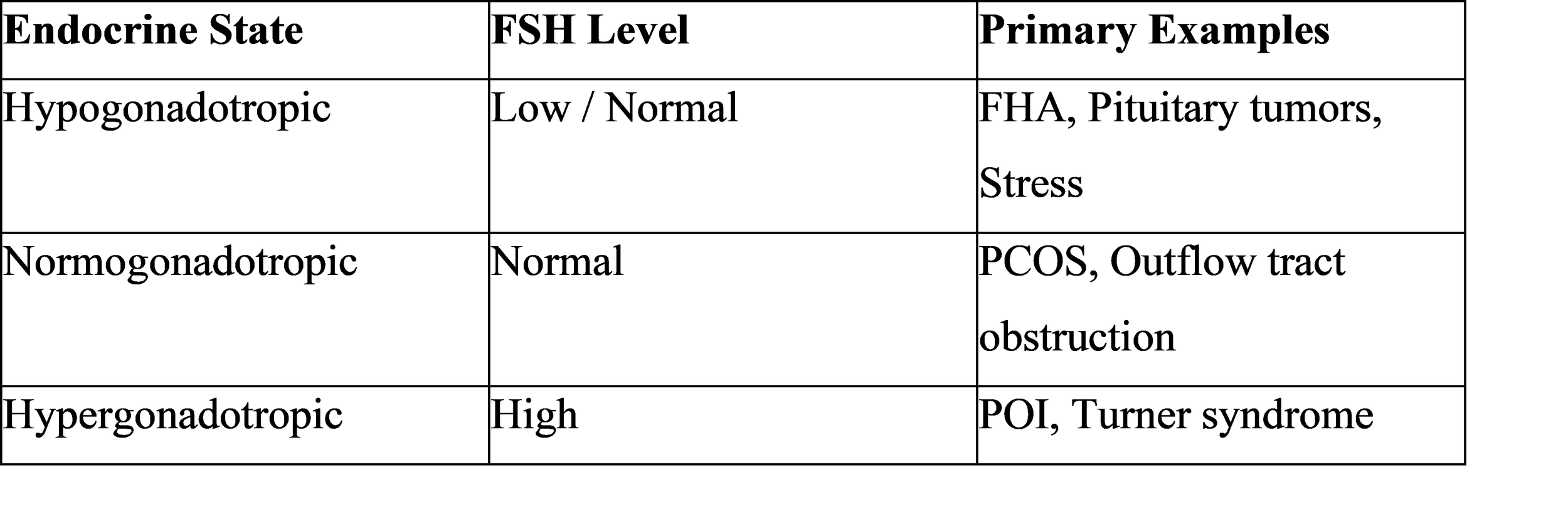

FHA is one of the most common forms of secondary amenorrhea, accounting for 20-35% of cases. It results from the suppression of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulses due to stressors such as excessive exercise, restricted caloric intake, or psychological stress. This suppression leads to low levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), causing a state of severe hypoestrogenism (estradiol levels often below 50 pg/ml).

2.2 Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

PCOS is a leading cause of normogonadotropic amenorrhea, characterized by chronic anovulation and hyperandrogenism. The 2023 International Evidence-Based Guideline refined the diagnostic criteria, allowing for the use of elevated anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels as an alternative to ultrasound for identifying polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM) in adults. In PCOS, persistently rapid GnRH pulses favor LH synthesis over FSH, impairing follicular maturation and leading to increased androgen production.

2.3 Primary Ovarian Insufficiency (POI)

POI involves the depletion or dysfunction of ovarian follicles before the age of 40. It is characterized by high FSH levels (hypergonadotropic hypogonadism) and low estrogen. Etiologies include chromosomal abnormalities (such as Turner syndrome), autoimmune disorders, or iatrogenic damage from chemotherapy or radiation.4

2.4 Anatomical and Structural Causes

Outflow tract obstructions can cause primary amenorrhea despite normal hormonal function. These include:

● Mullerian Agenesis: The congenital absence of the uterus and upper vagina.

● Imperforate Hymen or Transverse Vaginal Septum: Obstructions that prevent the exit of menstrual blood, often causing cyclic pelvic pain.

● Asherman Syndrome: Acquired intrauterine adhesions typically following uterine surgery or infection that prevent endometrial proliferation.

3. Diagnostic Evaluation

A systematic approach is essential to differentiate between hypo-, normo-, and hypergonadotropic etiologies.

3.1 Clinical History and Physical Exam

History should address exercise patterns, weight changes, stress, and medications. Physical examination must include body mass index (BMI) calculation, Tanner staging for breast and pubertal development, and assessment for signs of androgen excess like hirsutism or acne. Neurological signs such as headaches or vision changes may indicate a pituitary tumor.

3.2 Laboratory and Imaging Protocols

The initial workup for all patients includes:

● Pregnancy Test: The first step in all cases of secondary amenorrhea.

● Hormonal Panel: FSH, LH, estradiol, prolactin, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

● Androgen Screen: Total and free testosterone and DHEA-S if hyperandrogenism is suspected.

● Pelvic Ultrasound: To confirm the presence of a uterus and assess ovarian morphology.

● Brain MRI: Recommended if prolactin is significantly elevated or if there are central symptoms (e.g., persistent headaches or visual field defects).

4. Long-Term Health Consequences

Amenorrhea associated with hypoestrogenism has significant systemic implications beyond reproductive health.

4.1 Bone Mineral Density (BMD)

Estrogen is vital for bone homeostasis. In amenorrheic states, bone resorption outpaces formation. Patients with FHA, particularly those with anorexia nervosa, experience BMD declines of roughly 2.4% to 2.6% annually at the hip and spine.7 Because 90% of peak bone mass is achieved by age 18, amenorrhea during adolescence can lead to irreversible skeletal deficits and a doubled risk of fractures in adulthood.

4.2 Cardiovascular and Metabolic Health

Low estrogen levels are linked to unfavorable lipid profiles and impaired endothelial function, increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD).8 The 2023 PCOS guidelines emphasize that women with PCOS have a higher risk of myocardial infarction (OR 2.50) and stroke (OR 1.71), necessitating universal CVD risk assessment regardless of BMI.

5. Management and Treatment

Treatment is targeted at the specific underlying etiology and the patient's goals (e.g., symptom relief vs. fertility).

5.1 FHA and Energy Balance

The primary treatment for FHA is correcting the energy imbalance through nutritional adjustments and reduced exercise.10 Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is suggested as an effective psychological support to restore ovulatory cycles.10

5.2 Hormonal Therapy

● Estrogen Replacement: For those with POI or persistent FHA, transdermal estradiol with cyclic progestin is often used to protect bone health.10

● PCOS Management: Combined oral contraceptives are first-line for cycle regulation and hyperandrogenic symptoms, while metformin may address insulin resistance.

● Dopamine Agonists: Cabergoline or bromocriptine are used to treat hyperprolactinemia by shrinking pituitary adenomas.

5.3 Fertility Induction

If pregnancy is desired, pulsatile GnRH is the preferred first-line therapy for FHA as it mimics physiological rhythms. Gonadotropin therapy or clomiphene citrate are alternatives depending on the patient's endogenous estrogen status.

6. Conclusion

Amenorrhea serves as a critical clinical indicator of a woman's overall endocrine and metabolic status. Effective management requires early recognition, particularly in adolescents, to prevent long-term skeletal and cardiovascular morbidity. A multidisciplinary approach involving gynecologists, endocrinologists, and nutritionists remains the gold standard for restoring the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis and ensuring long-term health.

References

1. A practical guide to the diagnosis and management of amenorrhoea - PubMed, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9118817/

2. Amenorrhea - Gynecology and Obstetrics - Merck Manual ..., https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/gynecology-and-obstetrics/abnormal-uterine-bleeding/amenorrhea

3. Primary Amenorrhea - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf - NIH, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554469/

4. Secondary Amenorrhea - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431055/

5. Amenorrhea - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf - NIH, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482168/

6. Amenorrhea: Types, Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatment - Cleveland Clinic, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/3924-amenorrhea

7. Bone health in functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: What the endocrinologist needs to know - Frontiers, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/10.3389/fendo.2022.946695/full

8. Amenorrhea - Symptoms and causes - Mayo Clinic, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/amenorrhea/symptoms-causes/syc-20369299

9. Hypothalamic Amenorrhea and the Long-Term Health Consequences - PubMed Central, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6374026/

10. Hypothalamic Amenorrhea Guideline Resources | Endocrine Society, https://www.endocrine.org/clinical-practice-guidelines/hypothalamic-amenorrhea