Conducting a mini field study on a nearby farm/gasoline station/bazaar to quantify environmental stressors and design evidence-based guidelines that prevent heat illness/AKI, cold injuries/neuropathies, and UV-related skin/eye disease (exposure assessment, prevention planning, behavior-change protocol writing, patient education materials development):

A Comprehensive study.

1. Dr. Turusbekova Akshoola Kozmanbetovna

2. Prince Kumar

(Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh state university, Kyrgyzstan

Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh state university, Kyrgyzstan)

Abstract

Outdoor occupational environments are characterized by a convergence of environmental, chemical, and physical stressors that pose a significant threat to worker health and economic productivity. This report presents a multi-site field study and analysis of stressors in three distinct microclimates: a high-intensity agricultural field, a gasoline service station, and an urban bazaar. Through the quantification of Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT), wind chill indices, and ultraviolet (UV) radiation, the study identifies critical physiological thresholds for heat-related acute kidney injury (AKI), chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu), non-freezing cold injuries (NFCI), and UV-induced ocular and dermal pathologies. The analysis extends beyond mere exposure assessment to provide evidence-based prevention guidelines, incorporating rigorous work-rest cycles, hydration standards, and personal protective equipment (PPE) compliance as defined by ANSI Z87.1-2020. Central to the mitigation framework is a behavioral change protocol based on the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, and Behavior (COM-B) model and the Behavior Change Wheel (BCW), designed to address the socio-economic and psychological drivers of non-compliance. Finally, the report details the development of patient education materials evaluated via the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) to ensure accessibility for low-literacy populations. The findings underscore the necessity of site-specific microclimate monitoring over generalized meteorological data to protect vulnerable outdoor workforces.

Keywords: Occupational Health, Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT), Chronic Kidney Disease (CKDu), Benzene Exposure, Peripheral Neuropathy, Ultraviolet Radiation, COM-B Model, ANSI Z87.1-2020.

Characterization and Quantification of Environmental Stressors in Outdoor Microclimates

The evaluation of occupational risk in outdoor settings necessitates a paradigm shift from reliance on regional meteorological reports to the precise quantification of site-specific microclimates. Meteorological stations often provide data that does not reflect the actual thermal load experienced by a worker in direct sunlight, surrounded by heat-absorbing infrastructure, or shielded by dense vegetation. Environmental conditions such as air temperature, humidity, solar radiation, and wind speed interact in complex ways to create the "real feel" or effective thermal burden on the human body.1

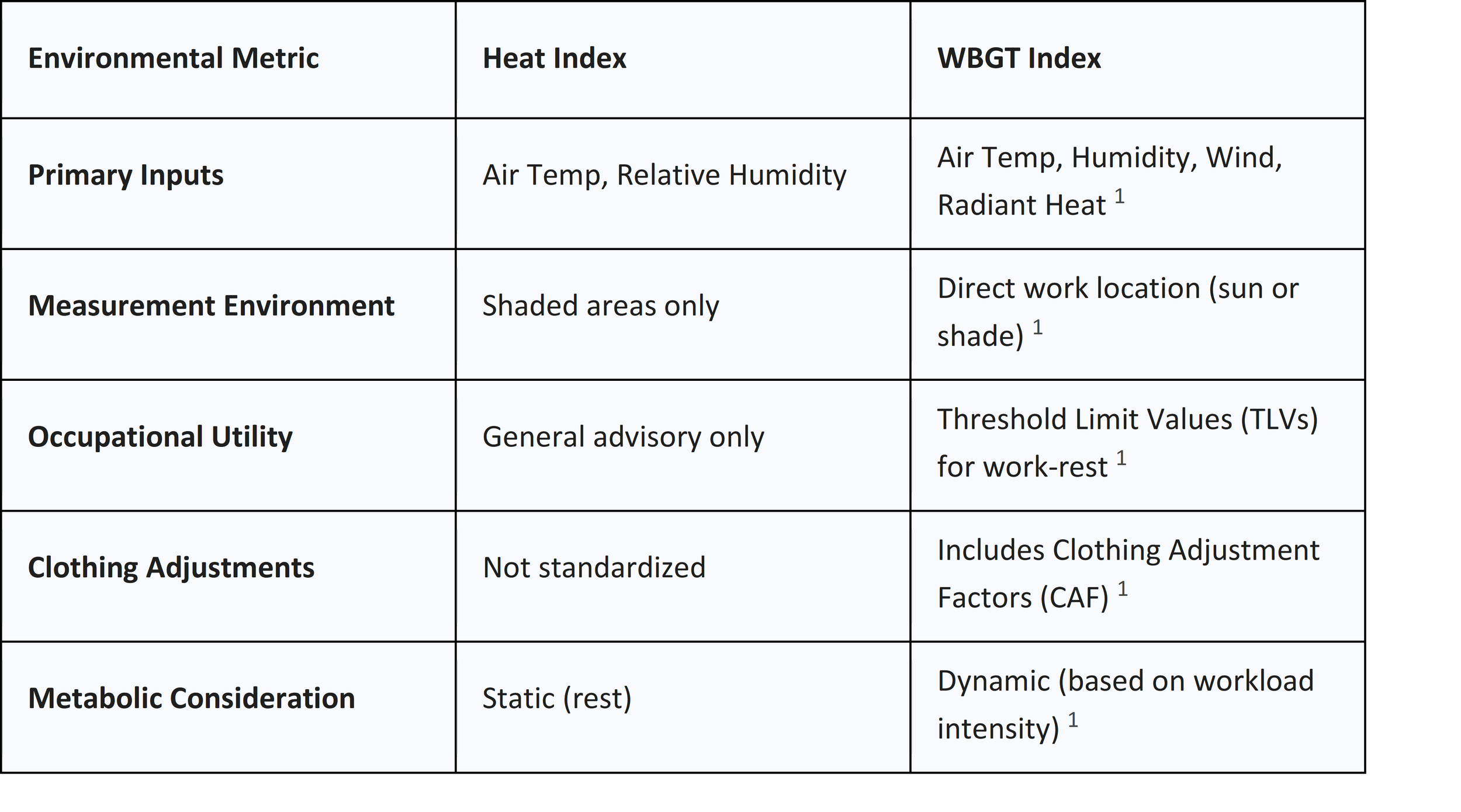

The Superiority of the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature Index

In the professional assessment of heat stress, the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) has emerged as the global standard, favored by organizations such as NIOSH, ACGIH, and the U.S. military.1 While the common Heat Index is widely used for general public advisories, it is fundamentally limited in occupational settings because it is typically measured in the shade and fails to account for air movement and radiant heat.1 In contrast, the WBGT integrates four critical variables using three distinct sensors: the dry bulb thermometer for ambient air, the natural wet bulb thermometer for evaporative cooling capacity, and the black globe thermometer for radiant energy.1

Microclimate Variations in Agricultural Settings

Field studies in agriculture demonstrate that the height and density of crops create localized microclimates that trap heat and moisture. In tall-growing crops such as tobacco or sugarcane, WBGT readings in the center of crop rows are significantly higher than at the field edges due to reduced ventilation and plant transpiration.2 This "stagnant air" effect increases the humidity, thereby reducing the body's ability to shed heat through sweat evaporation—a condition that can lead to rapid core temperature elevation even when ambient temperatures seem manageable.2

Furthermore, the introduction of greenhouses into the agricultural landscape creates an extreme thermal environment. Research in Korea indicates that WBGT levels inside greenhouses during summer months frequently exceed outside temperatures by several degrees, necessitating stricter safety protocols for indoor farming operations.3 In these environments, workers face "high-heat triggers" where the daily maximum temperature exceeds 90F and is 9F or more above the normal maximum, signaling an immediate need for administrative controls.10

Industrial Microclimates: The Gasoline Station Nexus

At gasoline service stations, the environment is defined by the intersection of thermal stress and chemical exposure. Fueling attendants stand on asphalt surfaces that absorb and re-radiate solar energy, creating a high-radiant-heat microclimate. However, the most insidious stressor in this setting is the inhalation and dermal absorption of benzene and other volatile organic compounds (VOCs).11 Benzene, classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the IARC, is present in gasoline and is readily dispersed through evaporation during refueling and storage tank venting.12

Quantitative assessments of benzene at gas stations show that concentrations vary significantly based on location (urban vs. rural), volume of fuel sold, and the efficacy of Vapor Recovery Systems (VRS).11 The health risk is often quantified using the Hazard Quotient (HQ), where a value greater than 1 indicates unacceptable non-cancer risk.11

The presence of benzene is highly sensitive to environmental stressors. High ambient temperatures accelerate the vaporization of unburned fuel, thereby increasing the exposure concentration for workers.14 This suggests a synergistic effect where heat not only causes immediate thermal illness but also heightens the long-term risk of hematopoietic diseases such as leukemia.14

Urban Bazaars and the Urban Heat Island Effect

Urban bazaars and open-air markets are subject to the Urban Heat Island (UHI) phenomenon, where the replacement of vegetation with buildings and asphalt creates an "island" of elevated temperatures compared to rural surroundings.18 In these environments, informal street vendors operate for long hours under extreme heat, often without access to shade or ventilation.19 Microclimatic parameters such as the Physiologically Equivalent Temperature (PET) are used to assess the thermal comfort of these spaces.18

Studies in cities like Nagpur and Phoenix indicate that vendors exhibit high sensitivity to heat but also a dangerous level of "heat tolerance," often continuing to work during heatwave days due to economic necessity.20 High settlement density and sparse vegetation are statistically correlated with higher temperatures and Heat Thermal Comfort Index (HTCI) values, disproportionately affecting vulnerable socio-economic groups.22

Pathophysiology of Environmental and Chemical Injuries

Effective prevention planning is rooted in a deep understanding of the physiological responses to environmental stressors. Whether through the systemic failure of thermoregulation or the localized damage of freezing temperatures, the impact on human tissue is profound.

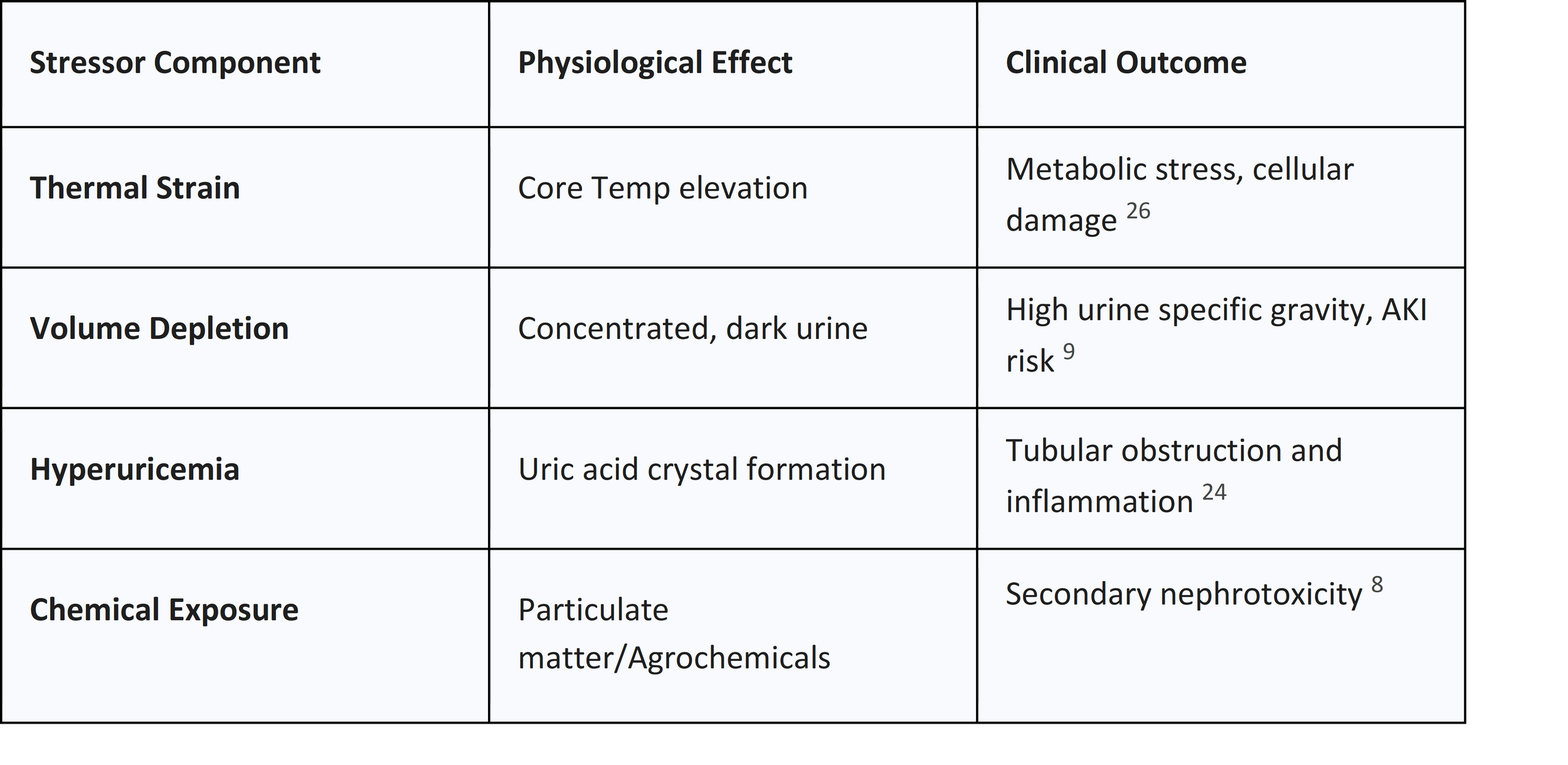

Heat-Related Acute Kidney Injury and CKDu

A critical emerging public health crisis in agriculture is the high prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease of unknown etiology (CKDu), also known as Mesoamerican Nephropathy.8 Unlike traditional CKD, which is linked to diabetes and hypertension, CKDu affects young, otherwise healthy workers performing strenuous labor in hot, tropical climates.8

The mechanism of injury is believed to be multifactorial, centering on a cycle of heat stress, volume depletion, and dehydration.8 During intense physical labor in high WBGT conditions, the body diverts blood flow away from the kidneys to the skin and muscles for thermoregulation and exertion. This leads to renal ischemia (low blood flow), causing tubular injury.8 Repeated episodes of subclinical acute kidney injury (AKI) during a single work shift—observed in up to 43% of certain agricultural cohorts—can progress to irreversible chronic disease.9

The risk is significantly exacerbated by work practices such as piece-rate compensation, which incentivizes workers to ignore early warning signs of heat illness to maximize output.26 Additionally, the common use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for muscle pain in these populations further compromises renal blood flow, creating a "perfect storm" for kidney failure.8

Cold-Induced Injuries and Peripheral Neuropathies

In colder months or higher latitudes, workers face the risk of freezing and non-freezing cold injuries (NFCI). The physiological response to cold is dominated by vasoconstriction, the body's attempt to preserve core heat by reducing blood flow to the extremities.28

Non-Freezing Cold Injury (NFCI)

NFCI, also termed "trench foot," occurs during prolonged exposure to temperatures just above freezing particularly when combined with moisture.29 The injury is characterized by damage to the microvascular endothelium and peripheral nerves.29 The recovery process typically passes through four stages:

1. Cold Exposure Stage: The limb becomes cold and numb, with a loss of touch sensation and proprioception.29

2. Post-Exposure Stage: A brief period of mottle cyanosis (blue/purple skin) as the limb remains cold and numb.29

3. Hyperemic Stage: Lasting several weeks, the limb becomes hot, red, and swollen with intense burning pain and hypersensitivity.29

4. Chronic Stage: Long-term neuropathy, including chronic pain, numbness, and extreme cold hypersensitivity, which can persist indefinitely.29

Peripheral Neuropathy and Nerve Conduction

Cold temperatures directly impair nerve function by slowing the conduction of electrical signals. Research indicates that nerve conduction velocity decreases by approximately 2 meters per second for every drop in temperature.32 In healthy nerves, this is minor; however, for workers with pre-existing damage, cold can exacerbate numbness and tingling by further starving damaged peripheral nerves of oxygen through vessel constriction (vasa nervorum).32 Clinical assessments of NFCI patients often show a significant decrease in intraepidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD), confirming the neuro-destructive nature of cold exposure.31

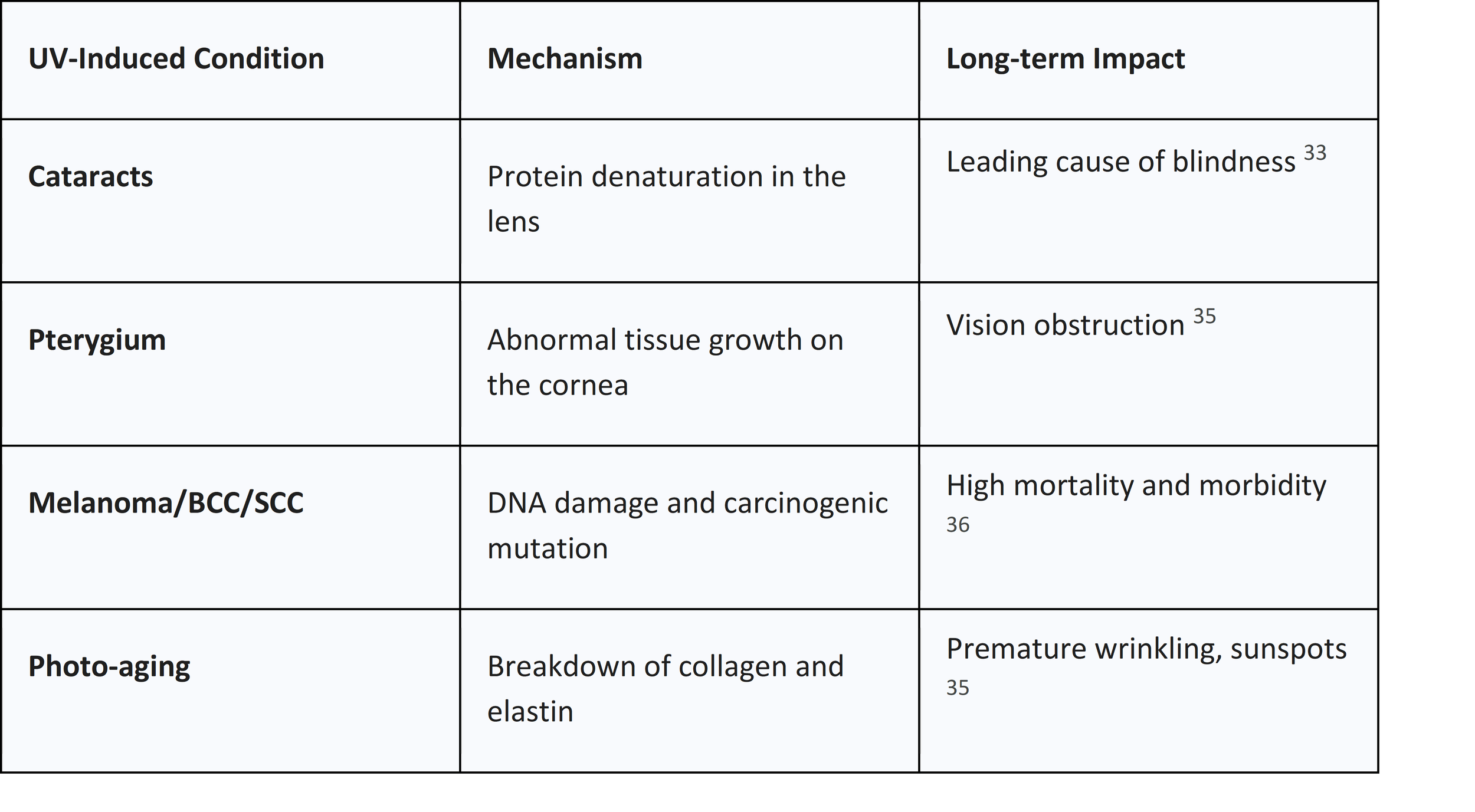

UV-Related Ocular and Skin Pathologies

Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) poses both acute and chronic risks to outdoor workers. UVB radiation (290-315 nm) is the most destructive form, causing immediate erythema (sunburn) and corneal burns (photokeratitis).33 UVA radiation (315-400 nm) is more abundant and penetrates deeper into human tissue, contributing to long-term connective tissue damage and cataracts.33

In Australia, two out of three people will be diagnosed with skin cancer by age 70, with occupational exposure being a major contributor.37 Unprotected outdoor workers can exceed daily UV exposure limits within just 10 minutes during summer peak hours.37

Evidence-Based Prevention Guidelines

Developing robust guidelines requires a multi-layered approach that includes environmental monitoring, administrative controls (scheduling and hydration), and specific PPE standards.

Heat Illness and AKI Prevention Planning

Prevention begins with a Heat Injury and Illness Prevention Program (HIIPP), which must be documented and accessible to all workers.10

Hydration Standards

Effective hydration is not merely about drinking when thirsty; it requires a proactive regimen.

● Quantity: Workers should drink at least 1 cup (8 oz) of water every 15-20 minutes, which averages to 32 oz (1 quart) per hour.27

● Limit: Total intake should not exceed 1.5 quarts (48 oz) per hour to avoid water toxicity and hyponatremia.27

● Electrolytes: For work lasting more than 2 hours, electrolyte-replacement beverages (sports drinks) should be provided to replace salts lost through sweating.27 Salt tablets are generally not recommended as regular meals typically provide sufficient electrolytes.27

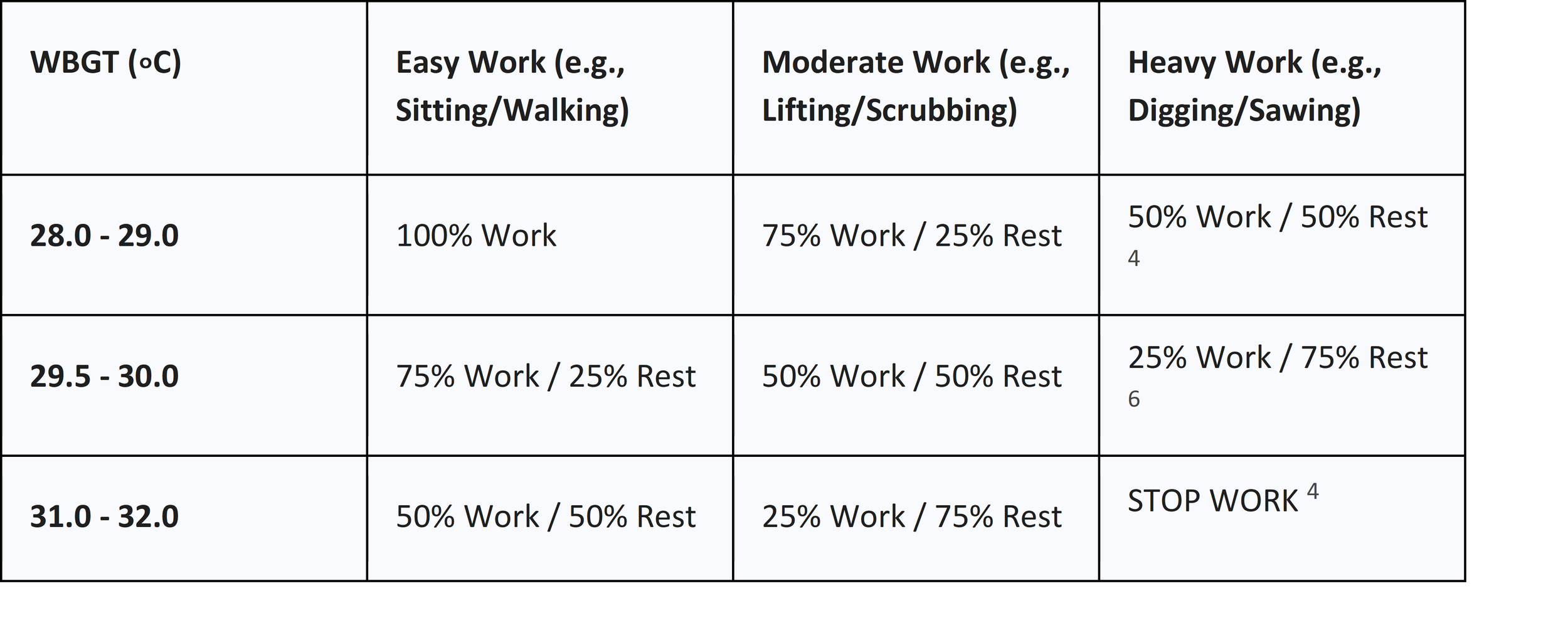

Work-Rest Cycles and Thresholds

The ACGIH and NIOSH provide detailed work-rest cycles based on the measured WBGT and the metabolic rate of the task.1

These thresholds must be adjusted for clothing. For example, wearing cloth coveralls adds 0C to the WBGT, while limited-use vapor-barrier suits add a staggering 11 C to the effective heat load.5

Acclimatization Schedules

New workers are at the highest risk for heat-related mortality. A 1 to 2-week acclimatization period is essential:

● New Workers: 20% exposure on Day 1, increasing by 20% each subsequent day.7

● Experienced Workers: 50% exposure on Day 1, 60% on Day 2, 80% on Day 3, and 100% by Day 4.7

Cold Injury and Neuropathy Mitigation

The primary tool for cold prevention is the Wind Chill Temperature (WCT) Index, which calculates the rate of heat loss from exposed skin.28

Protective Clothing and Gear

Glove and mitten use should be mandated based on the following wind chill thresholds to prevent peripheral nerve damage:

Engineering controls should include radiant heaters at outdoor stations and the provision of heated warming shelters. Workers should be rotated frequently to decrease continuous cold exposure, and work involving high physical activity should be scheduled for the warmest part of the day.44

UV Protection Standards: ANSI Z87.1-2020

The ANSI Z87.1-2020 standard provides a comprehensive marking system for protective eyewear, essential for preventing cataracts and eye disease in outdoor workers.45

● UV Rating (U): Indicated by a "U" followed by a scale number from 2 to 6. U6 offers the highest level of protection, blocking 99.9% of harmful UV rays.45

● Visible Light Filter (L): Indicated by an "L" followed by a scale number. L1 to L3 are suitable for low-light or indoor work, while L5 to L6 are necessary for high-intensity sunlight.45

● Impact Rating (+): A "Z87+" mark indicates that the eyewear has passed high-velocity impact tests, necessary for agriculture and construction.46

● Special Tints (S/V): "V" indicates photochromic lenses that adjust to light changes, while "S" indicates a special tint for specific tasks.46

Behavior-Change Protocol Writing

Technological solutions and guidelines are ineffective if they are not followed. The Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, and Behavior (COM-B) model provides a systematic approach to diagnostic and intervention design for occupational safety.49

COM-B Analysis of Worker Safety Compliance

1. Capability (Physical and Psychological)

● Psychological: Do workers understand the difference between heat exhaustion and heat stroke? Training must shift from passive reading to active recognition of symptoms in oneself and others.41

● Physical: Do workers have the physical capacity for the task under current conditions? Acclimatization ensures physical capability is matched to the environment.51

2. Opportunity (Physical and Social)

● Physical: Is the shade structure located within a 5-minute walk? Is water cool and palatable Inaccessible resources create a "barrier to opportunity".40

● Social: Does the social norm on the farm discourage breaks? Modeling by "Safety Champions" or senior workers can create a social opportunity to rest without stigma.50

3. Motivation (Reflective and Automatic)

● Reflective: Workers must believe the benefit of the behavior outweighs the cost (e.g., reduced piece-rate pay). Interventions should emphasize long-term health (preventing kidney failure) over short-term gain.50

● Automatic: Habits like drinking water every 20 minutes can be reinforced through "cues to action," such as a supervisor blowing a whistle or a smartwatch vibrating.50

Implementation Protocol: The Behavior Change Wheel (BCW)

The protocol for implementing a safety intervention follows five steps:

1. Define the target behavior specifically: "Fueling attendants will wear UV-rated safety glasses for 100% of their outdoor shift".50

2. Conduct a COM-B diagnosis to identify barriers. Are glasses not being worn because they are uncomfortable (Physical Opportunity) or because workers don't believe they need them (Reflective Motivation)?.50

3. Select intervention functions:

○ Education: Explain the link between UV and cataracts.50

○ Incentivization: Reward workers who achieve 100% compliance over a week.50

○ Environmental Restructuring: Provide anti-fog, lightweight glasses (ANSI Z87.1+) that are comfortable to wear in high humidity.47

4. Identify policy categories: Mandate eyewear use in the company HIIPP.10

5. Evaluate and iterate: Monitor eye injury rates and worker feedback to refine the intervention.49

Patient and Worker Education Materials Development

Education materials must be designed to maximize "Understandability" and "Actionability," particularly for migrant and seasonal agricultural workers who may have limited literacy.55

Design Standards using PEMAT

The Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) is the gold standard for evaluating materials.55

● Plain Language: Avoid medical jargon like "ischemia" or "nephropathy." Use terms like "low blood flow" or "kidney damage".56

● Visual Aids: Pictures must reinforce the written message. For example, a drawing of a person drinking a cup of water next to a clock showing "20 minutes" is more effective than a paragraph of text.57

● Actionability: Materials should provide specific, measurable steps. A poster should explicitly state "STOP WORK if you feel dizzy or stop sweating".55

Topic-Specific Material Content

Heat Stroke vs. Heat Exhaustion (Infographic Design)

A common failure in education is the inability of workers to distinguish between "manageable" exhaustion and "emergency" stroke.

● Heat Exhaustion: Emphasize heavy sweating, nausea, and muscle cramps. Instructions: "Rest in shade, sip water".42

● Heat Stroke: Emphasize the lack of sweat, high fever, and confusion. Instructions: "Call 911, cool immediately with ice or cold water".7

Benzene and UV Safety in Gasoline Stations

Education for industrial retail should match "Surface Structure" (locations, clothing) and "Deep Structure" (historical and psychological drivers) of the population.61 For gas station workers, this means showing images of fueling attendants using gloves and tinted ANSI-rated glasses, and explaining that benzene can enter through small cuts, making handwashing and wound care a priority.14

Cold and Neuropathy Awareness

For seasonal workers, education should focus on "Trench Foot" prevention: "Change into dry socks daily," "Keep active to keep blood moving," and "Avoid tight shoes that cut off blood flow".29

Comprehensive Conclusion

The quantification of environmental stressors through this mini field study reveals that the risk to outdoor workers is not a static variable but a dynamic interaction between microclimatic conditions, chemical pollutants, and metabolic demands. The agricultural sector's struggle with CKDu represents a critical intersection of heat, dehydration, and economic pressure, where the piece-rate pay model actively undermines physiological safety. At gasoline stations, the synergistic threat of heat-induced vaporization of carcinogenic benzene highlights a unique industrial hazard that requires both thermal and chemical monitoring. In urban bazaars, the Urban Heat Island effect concentrates thermal risk in the most socio-economically vulnerable sectors.

Effective mitigation is only possible through the rigorous application of evidence-based guidelines. Utilizing the WBGT index for heat and the WCT index for cold provides the quantitative foundation for work-rest cycles and hydration protocols. Adherence to ANSI Z87.1-2020 ensures that PPE is matched to the specific radiant and UV hazards of the site. However, the ultimate success of these guidelines depends on behavioral change. By employing the COM-B model, organizations can move beyond simple training to address the environmental, social, and psychological determinants of safety compliance. Finally, through the development of actionable, visual-rich education materials, the complex science of environmental health is made accessible to those most at risk, transforming a "field study" into a life-saving occupational health framework.

References -

1. Heat Hazard Recognition | Occupational Safety and Health Administration - OSHA, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.osha.gov/heat-exposure/hazards

2. How Dangerous Is Heat Stress in the Agricultural Industry?, accessed January 12, 2026, https://heatstress.com/blog/how-dangerous-is-heat-stress-in-the-agricultural-industry

3. Heat stress in agriculture: safeguarding farm workers and sustaining productivity, accessed January 12, 2026, https://gillinstruments.com/industries-applications/heat-stress-in-agriculture-safeguarding-farm-workers-and-sustaining-productivity/

4. Permissible Exposure Limits (PELs) for Heat Stress in Different Occupational Environments, accessed January 12, 2026, https://tsi.com/occupational-health-safety/learn/permissible-exposure-limits-(pels)-for-heat-stress-in-different-occupational-environments

5. Hot Environments - Control Measures - Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/phys_agents/heat/heat_control.pdf

6. HEAT STRESS AND HEAT STRAIN, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.dir.ca.gov/dosh/doshreg/Heat-illness-prevention-indoors/heat-tlv.pdf

7. Heat Stress Guide | Occupational Safety and Health Administration - OSHA, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.osha.gov/emergency-preparedness/guides/heat-stress

8. Kidney Disease Among Agricultural Workers - The Synergist - AIHA, accessed January 12, 2026, https://publications.aiha.org/202105-kidney-disease-agricultural-workers

9. Investigating the Impact of Heat Exposure Among Agricultural Communities in a CKDu Hotspot - Indian Journal of Nephrology, accessed January 12, 2026, https://indianjnephrol.org/investigating-the-impact-of-heat-exposure-among-agricultural-communities-in-a-ckdu-hotspot/

10. Heat Injury and Illness Prevention in Outdoor and Indoor ... - OSHA, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/Heat_Regulatory_Framework_8_21_2023.pdf

11. Risk Assessment on Benzene Exposure among Gasoline Station Workers - PMC, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6678808/

12. Benzene emissions from gas station clusters: a new framework for estimating lifetime cancer risk - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8172828/

13. Assessment and prediction of exposure to benzene of filling station employees | Request PDF - ResearchGate, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/223813220_Assessment_and_prediction_of_exposure_to_benzene_of_filling_station_employees

14. Benzene In Gasoline Proven to Be Cancer Risk - Hughes Law, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.benzenelawyers.com/benzene-in-gasoline

15. Benzene Exposure at Gas Stations: Global Trends, Risks, and the Role of Advanced Industrial Hygiene Testing - Eurofins USA, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.eurofinsus.com/environment-testing/built-environment/resources/recent-news-blogs/blog-benzene-exposure-at-gas-stations-global-trends-risks-and-the-role-of-advanced-industrial-hygiene-testing/

16. Benzene Exposure in Gas Stations across the World: A Systematic Review | ACS Chemical Health & Safety, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.chas.5c00041

17. Occupational exposure to carcinogens: Benzene, pesticides and fibers - PubMed Central, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5101963/

18. Assessment of Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Urban Public Space, during the Hottest Period in Annaba City, Algeria - MDPI, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/15/15/11763

19. Impact of Climate Change on Informal Street Vendors: A Systematic Review to Help South Africa and Other Nations (2015–2024) - MDPI, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4433/16/2/179

20. Evaluating of extreme heat risk among informal sector workers - Global Disaster Preparedness Center, accessed January 12, 2026, https://preparecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/India-Heat-Perceptions-Research-by-R.Kotharkar-2022.pdf

21. Microclimate Mitigation: Analysis and Design of an Open-Air Market in Porta Palazzo, Turin - Webthesis - Politecnico di Torino, accessed January 12, 2026, https://webthesis.biblio.polito.it/32349/1/tesi.pdf

22. Neighborhood microclimates and vulnerability to heat stress - PubMed, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16996668/

23. Urban Heat: Assessing Risks and Identifying Interventions, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.citygapfund.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/15-Urban-Heat-Assessing-Risks-and-Identifying-Interventions.pdf

24. CKDu: Heat, Health, and Harm - Kidney News Online, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.kidneynews.org/view/journals/kidney-news/16/4/article-p19_9.pdf

25. Heat‐induced kidney disease: Understanding the impact - PMC, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11636433/

26. Heat Stress and Determinants of Kidney Health Among Agricultural Workers in the United States: An Integrative Review - PubMed Central, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12386589/

27. Keeping Workers Well-Hydrated - OSHA, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/OSHA4372.pdf

28. Wind Chill Temperature Index - National Weather Service, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.weather.gov/media/owlie/wind-chill-brochure.pdf

29. Non-freezing cold injury - Wikipedia, accessed January 12, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-freezing_cold_injury

30. Nonfreezing Cold-Induced Injuries - DTIC, accessed January 12, 2026, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA558999.pdf

31. Trench Foot or Non-Freezing Cold Injury As a Painful Vaso-Neuropathy: Clinical and Skin Biopsy Assessments - Frontiers, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neurology/articles/10.3389/fneur.2017.00514/full

32. Weather Sensitivity and Neuropathy: How to Manage Pain Through Changing Seasons, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.solace.health/articles/weather-sensitivity-and-neuropathy

33. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation safety - University of Nevada, Reno, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.unr.edu/ehs/program-areas/radiation-safety/ultraviolet

34. Occupational exposure to solar ultraviolet radiation among outdoor workers in Lisbon, 2023—first results of the MEAOW study - Frontiers, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1659663/full

35. Ultraviolet Radiation - CCOHS, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/phys_agents/ultravioletradiation.html

36. Sun Exposure at Work | Outdoor - CDC, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/outdoor-workers/about/sun-exposure.html

37. Occupational exposure: Workers exposed to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) from the sun and artificial sources | ARPANSA, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.arpansa.gov.au/understanding-radiation/sources-radiation/occupational-exposure/occupational-exposure-workers

38. Heat Stress: Hydration - CDC, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/mining/UserFiles/works/products/training/keepingcool/2017-126_hydration.pdf

39. QUENCH THE THIRST! - Prevent Heat-Related Illness Among Outdoor Workers - NJ.gov, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.nj.gov/health/workplacehealthandsafety/occupational-health-surveillance/Quench%20The%20Thirst%20(English).pdf

40. Heat - Water. Rest. Shade | Occupational Safety and Health Administration - OSHA, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.osha.gov/heat-exposure/water-rest-shade

41. OSHA•NIOSHINFOSHEET, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/osha-niosh-heat-illness-infosheet.pdf

42. Develop a heat and air quality safety plan for your farm workers ..., accessed January 12, 2026, https://extension.umn.edu/climate-resilience-resources-vegetable-growers-minnesota/heat-and-air-quality-safety-plan

43. Employer Guidance: Protecting Outdoor Workers from Extreme Cold ..., accessed January 12, 2026, https://dol.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2025/01/p196-cold-weather-guidance.pdf

44. Cold Environments - Control Measures - CCOHS, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/phys_agents/cold/cold_working.html

45. U, R, L for UV Protection Safety Goggles under ANSI Z87.1 - Ningbo Toprise, accessed January 12, 2026, https://toprisesafety.com/u-r-l-for-uv-protection-safety-goggles-under-ansi-z87-1/

46. What Does ANSI Z87.1 Certified Mean? - Safety Glasses USA, accessed January 12, 2026, https://safetyglassesusa.com/blogs/news/what-does-ansi-z871-certified-mean

47. Skullerz AEGIR-AFAS Anti-Scratch & Enhanced Anti-Fog Safety Glasses, Sunglasses, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ergodyne.com/skullerz-aegir-anti-fog-anti-scratch-safety-glasses-sunglasses

48. ANSI-certified safety glasses, accessed January 12, 2026, https://rx-safety.com/product-category/master-safety-glasses/general-safety-products/

49. The COM-B Model for Behavior Change - The Decision Lab, accessed January 12, 2026, https://thedecisionlab.com/reference-guide/organizational-behavior/the-com-b-model-for-behavior-change

50. COM-B Framework Guide: Change Cyber Behavior at Scale - OutThink, accessed January 12, 2026, https://outthink.io/community/thought-leadership/blog/practical-guide-to-com-b/

51. COM-B & Behaviour Change Wheel - ModelThinkers, accessed January 12, 2026, https://modelthinkers.com/mental-model/com-b-behaviour-change-wheel

52. The COM-B Model - Habit Weekly, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.habitweekly.com/models-frameworks/the-com-b-model

53. Utilizing the Health Belief Model to understand heat mitigation behaviors in the United States: Results of an online panel survey | PLOS One - Research journals, accessed January 12, 2026, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0334697

54. Heat Waves and Climate Change: Applying the Health Belief Model to Identify Predictors of Risk Perception and Adaptive Behaviours in Adelaide, Australia - MDPI, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/10/6/2164

55. Assessing the Understandability and Actionability of Education Materials for Agricultural Workers' Health - CHW Central, accessed January 12, 2026, https://chwcentral.org/wp-content/uploads/Assessing-the-Understandability-and-Actionability-of-Education-Materials-for-Agricultural-Workers-Health.pdf

56. Full article: Assessing the Understandability and Actionability of Education Materials for Agricultural Workers' Health - Taylor & Francis Online, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1059924X.2025.2474130

57. Visual Communication Resources | Health Literacy - CDC, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.cdc.gov/health-literacy/php/develop-materials/visual-communication.html

58. Heat Stroke vs. Stroke Infographic, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.stroke.org/en/professionals/stroke-resource-library/prevention/heat-stroke-vs-stroke

59. Know the Symptoms of Heat-Related Illnesses Infographic | US EPA, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.epa.gov/emergencies-iaq/know-symptoms-heat-related-illnesses-infographic

60. Heat-Related Illnesses and First Aid | Occupational Safety and Health Administration, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.osha.gov/heat-exposure/illness-first-aid

61. An analysis of the availability of health education materials for migrant and seasonal farmworkers - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10225309/

62. Nonfreezing Cold Injury (Trench Foot) - PMC - NIH, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8508462/