Diabetes Insipidus

1. Osmonova G. Zh.

2. Sahil Ravindra Akare

(Teacher, Dept. of Pediatrics, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Kyrgyzstan)

(Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Kyrgyzstan)

Abstract

Diabetes insipidus is a condition where an individual is unable to concentrate urine. This can happen due to a lack of vasopressin secretion in central diabetes insipidus, the kidney's insensitivity to vasopressin in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, or excessive water intake in primary polydipsia. The clinical signs of diabetes insipidus include increased thirst, frequent urination, and night time urination. Central diabetes insipidus usually develops slowly, while nephrogenic diabetes insipidus progresses gradually. Advances in clinical, laboratory, imaging, and molecular biology methods have improved the diagnosis of diabetes insipidus. For idiopathic diabetes insipidus, the correct diagnosis is now possible in 10%-20% of patients, compared to the previous rate of 50%. This allows for earlier treatment and reduces the chances of complications. It is essential to differentiate secondary diabetes insipidus, which can involve issues like nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, brain tumors, head injuries, autoimmune problems, or central nervous system infections in patients with central diabetes insipidus. For management, there is a critical need to use desmopressin, an analogue for diabetes insipidus treatment. Adjusting fluid intake, along with using diuretics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, may help manage nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.

Introduction

The term diabetes comes from Greek, meaning “siphon,” derived from the verb *diabaine*, which means “to go through” or “to stand with legs apart, as in urination.” Insipidus is Latin for “without taste.” Unlike diabetes mellitus (DM), which involves sweet-smelling urine, diabetes insipidus (DI) results in flavorless urine due to its low sodium content. DI is rare but serious. It can be life-threatening because it causes fluid imbalance leading to severe dehydration and electrolyte disturbances.

DI is characterized by excessive thirst, frequent urination, high sodium levels, and dehydration. The most common type is Central Diabetes Insipidus (CDI), which is caused by a deficiency of arginine vasopressin (AVP), also known as antidiuretic hormone (ADH). CDI is referred to in the literature as pituitary, hypothalamic, neurohypophyseal, or neurogenic diabetes. The second most common type is nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NID), which results from the renal tubules' resistance to ADH. NDI can be primary (idiopathic) or secondary due to drugs or chronic conditions like renal failure or polycystic kidney diseases.

Epidemiology

Diabetes Insipidus (DI) is characterized by the inability to concentrate urine secondary to vasopressin deficiency or to vasopressin resistance resulting in polyuria. DI is rare, with a prevalence estimated at 1:25,000; fewer than 10% of cases are hereditary in nature [1]. Central DI (CDI) accounts for greater than 90% of cases of DI and can present at any age, depending on the cause. No prevalence for hereditary causes of CDI has been established. Nephrogenic DI (NDI) is less frequent.

Pathophysiology

Arginine vasopressin (ADH) is an anti-diuretic hormone. It is usually carried in the blood to receptor sites on the basolateral surface of the collecting duct membrane. When the ADH receptor is activated, it increases cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production through a G protein and adenylate cyclase coupling. This stimulation activates protein kinase A, leading to enhanced recycling of aquaporin proteins in the plasma membrane. This process improves water entry into the cell from the lumen. If the ADH receptor is absent, this process cannot occur, leading to reduced water intake and polyuria. On the other hand, defective or absent aquaporin can also impair the process when there is a normal arginine vasopressin receptor (AVPR2 or V2 receptor). There are different types of receptors for vasopressin. The V1 receptor, found in endothelial cells, causes a pressor effect through the activation of the calcium pathway, while the V2 receptor is responsible for water reabsorption by activating cAMP in the kidneys and opening aquaporin channels. Many factors can stimulate vasopressin secretion, including nausea, acute hypoglycemia, glucocorticoid deficiency, and smoking. However, the main stimulus is increased plasma osmolality, which can rise by as little as 1%. The baro-regulatory system usually does not trigger vasopressin secretion under normal conditions unless there is significant volume loss, in which case, some of this hormone is released. Vasopressin works as an antidiuretic by reabsorbing water through the principal cells of the collecting ducts and the thick ascending loop of Henle. This process increases blood plasma volume and lowers plasma osmolality. It can also cause the smooth muscles in blood vessels to contract and release von Willebrand factor.

Central DI

The onset can be acute due to trauma and neurosurgical procedures in CDI and slow in other non-trauma cases. The age at onset can be variable. Severe cases occurring in the neonatal period are rare in CDI. The familial form of CDI can onset at 5-6 years and may be as late as the third decade. The infantile onset can be seen in the familial form due to Autosomal Recessive inheritance. The onset may be variable in Wolfram syndrome Diabetes Insipidus, Diabetes Mellitus, Optic Atrophy, and Deafness syndrome (DIDMOAD) Syndrome. Developmental anomalies in mid-line brain structures such as Septo-Optic Dysplasia; holoprosencephaly; Pituitarary hypoplasia and stalk defects; Corpus callosal agenesis etc., can have earlier onset. They also have impaired thirst perception. Minor trauma to the base of the brain may induce temporary or permanent CDI in an individual and in 50% cases of fracture sella Turcica; CDI can be delayed even up to 1 month following trauma.

Nephrogenic DI

Kids usually get NDI from something they catch, not from birth.[2] If they're born with it, it's worse and harder to deal with.[1,4] X-linked NDI mostly hits boys, but girls can get it too if their X chromosome acts weird.[4,10] This type shows up early, like in the first week. Really bad cases can cause too much fluid around the baby in the womb and early delivery. Some kids might pee and drink a lot after they stop breastfeeding because breast milk doesn't have much salt and protein, so their kidneys don't have to work as hard.[4] They get way thirstier than with CDI, and it's hard to quench. They might keep getting fevers, throwing up, getting dehydrated, and doctors might think it's sepsis. They don't grow well either. Unlike CDI, they can have brain problems that slow them down, probably because of calcium buildup in the brain.

NDI can also come from medicines like lithium, demeclocycline, foscarnet, clozapine, amphotericin B, methicillin, and rifampin. Too much calcium or too little potassium can also make you pee a lot, but we don't know exactly why. You might even feel poop stuck in their belly, along with a big bladder and sometimes swollen kidneys from water buildup.

If someone just drinks a lot, it usually starts slowly. If they don't have to pee at night, don't need water then, it doesn't mess up their day, and they're growing okay, then it's probably not a disease.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing diabetes insipidus (DI) can be tricky because the non-specific symptoms—such as excessive crying, inability to feed, failure to thrive, and irritability—are common in many infants. Therefore, a high level of suspicion is important. In addition to a thorough medical and physical exam, which includes the child’s daily fluid intake, diet, medications, and bowel and bladder habits, diagnosing this condition may involve the following: Assessing the specific gravity of the first morning urine can be helpful. In suspected cases of DI, accurate 24-hour urine output measurement is crucial to confirm polyuria. The presence of diluted urine alongside high serum sodium levels and increased serum osmolality confirms the diagnosis of DI. Serum sodium levels may be elevated, exceeding 150 mmol/L, and serum osmolality can be greater than 300 mosmol/kg. If serum osmolality is over 300 mosmol/kg along with low urinary osmolality (under 300 mosmol/kg) in cases of pathological polyuria and polydipsia, DI is definitive.

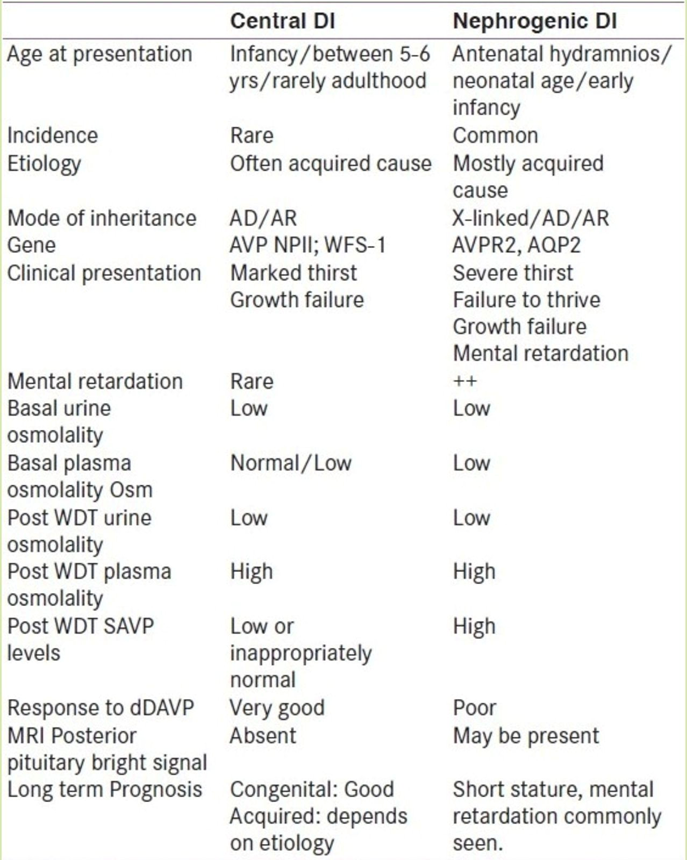

Blood tests for potassium and calcium levels are also necessary to rule out secondary polyuria due to hypokalemia and/or hypercalcemia, which may hinder the kidney’s ability to concentrate urine. The water deprivation test (WDT) establishes the diagnosis of DI and helps to differentiate central DI (CDI) from nephrogenic DI (NDI) based on responses to a vasopressin analog. Ideally, an experienced professional should conduct the WDT. Positive responses would include increased urine osmolality over 450 mosmol/kg, a urine to serum osmolality ratio of 1.5, and increased urine concentration relative to serum osmolality of 1.

In cases of CDI, a response to water deprivation occurs, while in NDI, there is no response to ADH. Patients with CDI may show a limited ability to concentrate urine, with a partial response also seen in NDI. Therefore, distinguishing between CDI, NDI, and central DI can be challenging since all conditions can produce similar rises in urinary osmolality during the WDT. The hypertonic saline test offers an alternative approach to the WDT, assisting in the diagnosis of DI and other conditions causing high urine production. This test looks at the relationship between serum osmolality and blood levels of arginine vasopressin (AVP). This method is well-established in adults, although it has limited application in children. Mohn et al. from the UK used this test in five children (aged 11 months to 18 years) with diagnostic issues. An MRI of the pituitary and hypothalamus is vital for evaluating the underlying cause of CDI and should always include a post-gadolinium contrast examination to look for an ectopic hypertrophy focus. Renal ultrasonography is helpful for ruling out primary renal problems like polycystic kidney disease and ureter obstruction. Mega hydronephrosis and mega-ureter are often found in children with prolonged polyuria and polydipsia. Genetic studies are available for familial forms of CDI and NDI.

Management

The first step in managing DI is to educate patients about the condition and how to manage it. The main goals of management are to reduce polyuria and thirst so patients can thrive and maintain a normal lifestyle. This can be achieved in various ways. Patients should have unrestricted access to water. For those with DI, drinking enough fluid can compensate for urine losses. If oral replacement fails due to hypernatremia, the same losses can be adjusted with dextrose in water or IV hypotonic fluids based on the patient's serum osmolality. Patients with DI should drink enough to replace urine losses.

Prognosis

Central DI that occurs after pituitary surgery typically resolves within days to weeks. However, if the stalk is injured, central DI may become permanent. The clinical course of central DI is generally more of an inconvenience than a life-threatening issue. The current treatment option, Desmopressin, effectively controls symptoms, but patients must be closely monitored for adverse reactions and complications like water intoxication and hypernatremia. The prognosis for NDI is generally good if the underlying cause can be addressed.

Conclusion

DI is not uncommon in pediatrics. Its presentation can vary depending on the age of onset and underlying cause. The water deprivation test can be useful for confirmation when presentations are atypical and for distinguishing between causes. It should be performed under close supervision by trained personnel knowledgeable about the test. The management plan for DI primarily focuses on treating the underlying cause. Desmopressin is the preferred medication for CDI, with oral forms being more favored. A combination of oral thiazide diuretics has proven effective for treating NDI.