Diabetes Mellitus in Children

1. Manickavel Surya Nithish

2. Osmonova G. Zh.

(Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Kyrgyzstan)

(Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Kyrgyzstan)

Abstract:

Diabetes mellitus in childhood is a significant and growing public health challenge worldwide. This article explores the epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnosis, management, complications, and preventive strategies relevant to children and adolescents. We include key graphs and diagrams to illustrate important trends and mechanisms.

1. Introduction

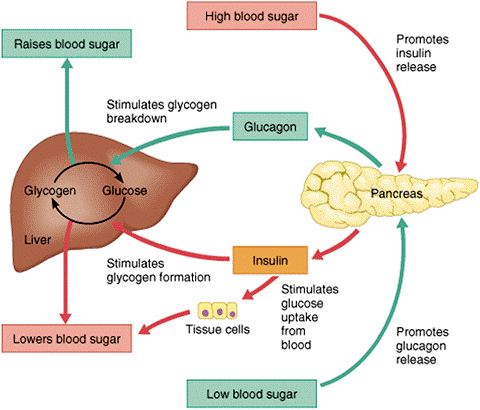

Diabetes mellitus (DM) refers to a group of metabolic diseases characterized by chronic hyperglycemia — elevated blood glucose — resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. In children and adolescents, diabetes can present differently than in adults, with unique clinical features and implications for growth and development.

There are multiple forms of diabetes that may occur in children:

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM): Autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells leading to absolute insulin deficiency—most common in children.

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM): Insulin resistance with relative insulin deficiency—previously rare in children but rising globally.

Monogenic diabetes and neonatal diabetes: Rare genetic causes.

Secondary diabetes: Due to other conditions like cystic fibrosis or steroid use.

T1DM is historically the dominant form in children, but T2DM is increasing in parallel with obesity and lifestyle changes.

2. Epidemiology

Understanding the global patterns of childhood diabetes helps guide screening, prevention, and resource allocation.

2.1 Global Incidence and Trends

Worldwide, the incidence of childhood diabetes has increased steadily over recent decades.

From 1990 to 2019, incident cases of childhood diabetes increased by about 39.4%, with the global incidence rate rising from 9.31 to 11.61 per 100,000 children.

The greatest increases occurred in children aged 10–14 years and in middle-income regions.

2.2 Type Distribution

T1DM accounts for 80–90% or more of pediatric diabetes globally.

T2DM among pediatric cases is smaller but growing rapidly in many countries, particularly where childhood obesity rates are climbing.

2.3 Regional Variability

Geography matters:

Rates vary widely, with Finland historically having some of the highest rates of pediatric T1DM (~30+ per 100,000).

Incidence is increasing significantly in low and middle-income countries, sometimes faster than in high-income regions.

3. Pathophysiology

Diabetes is not one disorder — it is a syndrome of hyperglycemia, and mechanisms differ:

3.1 Type 1 Diabetes

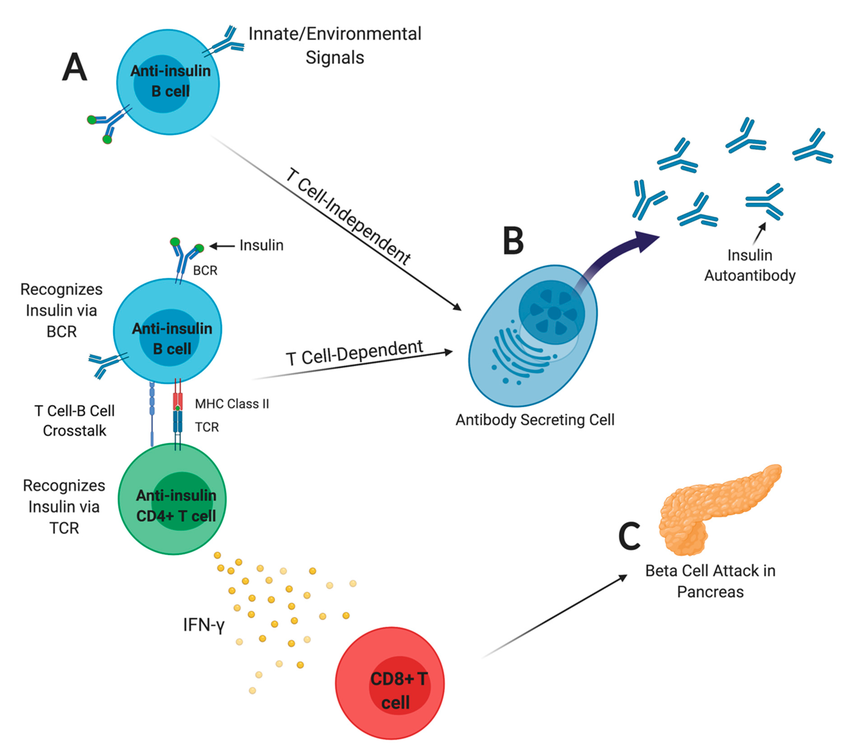

T1DM is caused by autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells — the cells that produce insulin. Genetic predisposition plus environmental triggers (viral infections, early diet, etc.) are thought to provoke the autoimmune attack. The hallmark is an absolute lack of insulin.

Diagram Explanation: Beta cells in the islets of Langerhans are progressively destroyed by activated immune cells. Without insulin, glucose cannot enter tissues — leading to high blood glucose and energy starvation despite abundant glucose in the bloodstream.

3.2 Type 2 Diabetes

T2DM arises from insulin resistance — tissues fail to respond to insulin — initially compensated by increased insulin production, followed by beta-cell dysfunction.

In children, this is commonly linked to:

Obesity

Sedentary lifestyle

Genetic predisposition

T2DM typically presents in adolescents, often with features of metabolic syndrome (obesity, high lipids, high blood pressure).

4. Clinical Presentation

4.1 Common Symptoms

Diabetes symptoms often relate to high glucose levels and dehydration:

Polyuria (frequent urination)

Polydipsia (increased thirst)

Polyphagia (increased hunger) despite weight loss

Fatigue

Blurred vision

In young children, symptoms can be subtle or nonspecific. For T1DM, onset can be rapid.

4.2 Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA)

DKA is a life-threatening emergency, especially in T1DM:

Marked hyperglycemia (often > 250 mg/dL)

Ketone production

Metabolic acidosis

Dehydration

It presents with vomiting, abdominal pain, rapid breathing, and altered consciousness. Early recognition and immediate care save lives.

5. Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on blood glucose measurements:

Fasting Plasma Glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL

Random Plasma Glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL + symptoms

HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (reflects average glucose over ~3 months)

For T1DM, autoantibody testing (e.g., GAD65, IA-2) may help confirm autoimmune etiology.

6. Management and Treatment

6.1 Type 1 Diabetes

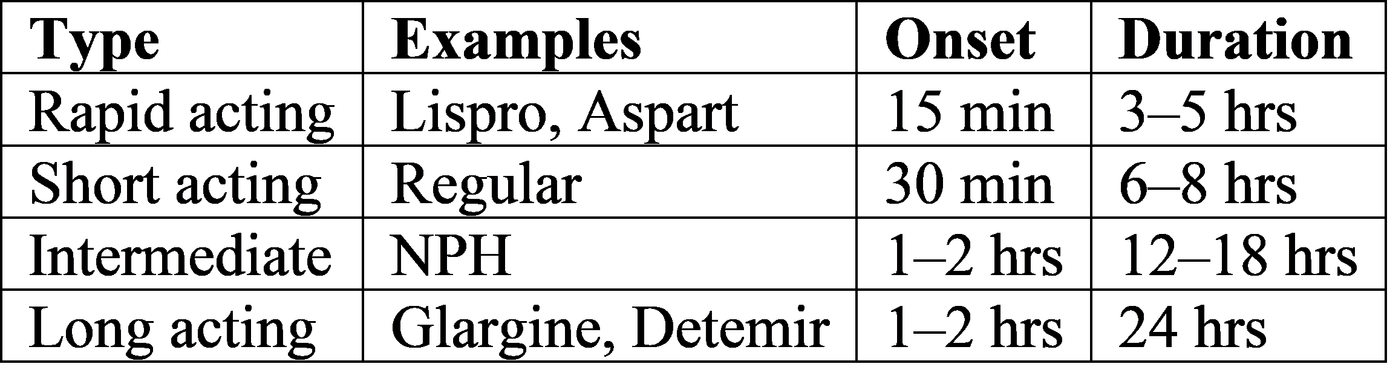

There is no cure — treatment centers on insulin therapy:

Multiple daily injections or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (pump)

Frequent glucose monitoring (finger stick or CGM)

Nutrition planning

Physical activity adjustments

6.2 Type 2 Diabetes

Focuses on:

Lifestyle changes (diet, exercise)

Oral medications (e.g., metformin)

Insulin in some cases

Children with T2DM often need multidisciplinary care — involving dietitians, endocrinologists, and psychologists.

7. Complications

Long-term complications stem from chronic hyperglycemia:

7.1 Microvascular

Retinopathy (eye damage)

Nephropathy (kidney disease)

Neuropathy (nerve damage)

7.2 Macrovascular

Cardiovascular disease risk increases over time — even in youth with poorly controlled diabetes.

7.3 Acute Complications

Hypoglycemia (low blood glucose)

DKA

Both are preventable with good monitoring and education.

8. Growth, Development, and Adolescence

Children with diabetes face unique challenges:

Growth spurts alter insulin needs

Puberty induces insulin resistance

Peer dynamics influence adherence to management plans

Psychological support is essential.

9. Prevention and Public Health

9.1 Primary Prevention (T1DM)

Currently no proven method prevents T1DM onset. Research on immune modulation and early diet continues.

9.2 Preventing T2DM

This is actionable:

Promote healthy diet and physical activity

Reduce childhood obesity

Screen at-risk groups (family history, obesity)

Public campaigns and school programs are key.

10. Future Directions

Research themes include:

Immunotherapy to delay or prevent T1DM

Better artificial pancreas technologies

Genetic predictors of monogenic diabetes

11. Classification of Diabetes Mellitus in Children

Diabetes mellitus in children is a heterogeneous group of disorders, not limited to only type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

11.1 Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

Autoimmune (Type 1A) – most common

Idiopathic (Type 1B) – no identifiable autoantibodies

Characterized by absolute insulin deficiency

11.2 Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Insulin resistance with relative insulin deficiency

Increasing prevalence in adolescents

Strong association with obesity and family history

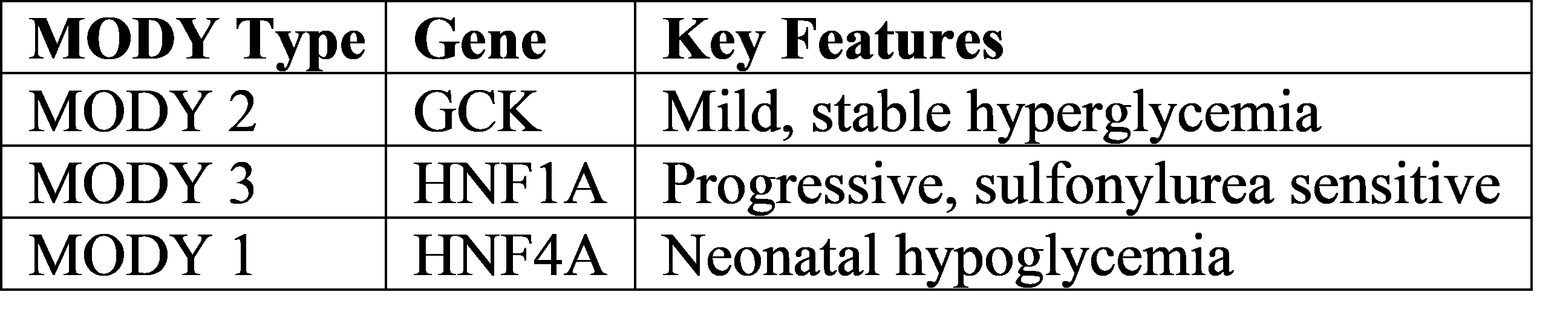

11.3 Monogenic Diabetes

Includes:

Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY)

Neonatal diabetes (onset before 6 months of age)

Important because some forms do not require insulin and respond to oral agents.

Table: Common MODY Types

11.4 Secondary Diabetes

Occurs due to:

Cystic fibrosis

Chronic pancreatitis

Endocrine disorders (Cushing syndrome)

Drug-induced (glucocorticoids, chemotherapy)

12. Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors

12.1 Genetic Susceptibility

Strong association with HLA class II genes (DR3, DR4, DQ2, DQ8)

Sibling risk: ~6–7%

Twin concordance: ~30–50%

12.2 Environmental Triggers

Proposed triggers include:

Viral infections (Coxsackie B, rubella)

Early exposure to cow’s milk proteins

Vitamin D deficiency

Gut microbiome alterations

These factors may initiate autoimmune beta-cell destruction in genetically predisposed children.

13. Pathogenesis of Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA)

DKA is a catabolic state caused by insulin deficiency and excess counter-regulatory hormones.

Pathophysiological Sequence

Absolute insulin deficiency

Increased glucagon, cortisol, catecholamines

Increased gluconeogenesis and lipolysis

Free fatty acids converted to ketone bodies

Metabolic acidosis + dehydration

14. Laboratory Evaluation in Pediatric Diabetes

14.1 Routine Investigations

Fasting and random blood glucose

HbA1c

Urine ketones

Serum electrolytes

14.2 Autoimmune Markers (T1DM)

Anti-GAD antibodies

Islet cell antibodies (ICA)

Insulin autoantibodies (IAA)

Anti-IA-2 antibodies

14.3 C-Peptide Levels

Low or absent → Type 1 DM

Normal or high → Type 2 or MODY

15. Nutritional Management in Children with Diabetes

Nutrition is not restrictive, but balanced and individualized.

15.1 Key Principles

Age-appropriate caloric intake

Consistent carbohydrate distribution

Avoid refined sugars

Encourage fiber-rich foods

15.2 Carbohydrate Counting

Allows flexible insulin dosing

Essential in intensive insulin therapy

16. Insulin Therapy – Advanced Concepts

16.1 Types of Insulin

16.2 Insulin Delivery Methods

Syringes

Insulin pens

Insulin pumps

Hybrid closed-loop systems (artificial pancreas)

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) improves glycemic control and reduces hypoglycemia.

17. Hypoglycemia in Children with Diabetes

17.1 Causes

Excess insulin

Missed meals

Exercise without adjustment

17.2 Symptoms

Tremors

Sweating

Confusion

Seizures (severe cases)

17.3 Management

Oral glucose (15 g rule)

IV dextrose or glucagon injection for severe cases

18. Psychosocial Aspects of Pediatric Diabetes

Diabetes affects mental health, especially in adolescents.

Common Issues

Diabetes distress

Anxiety and depression

Eating disorders (diabulimia)

Poor adherence during adolescence

Psychological counseling is essential for long-term outcomes.

19. Diabetes and School Life

Schools must support children with diabetes:

Access to glucose monitoring

Permission to eat snacks

Emergency hypoglycemia management

Teacher awareness programs

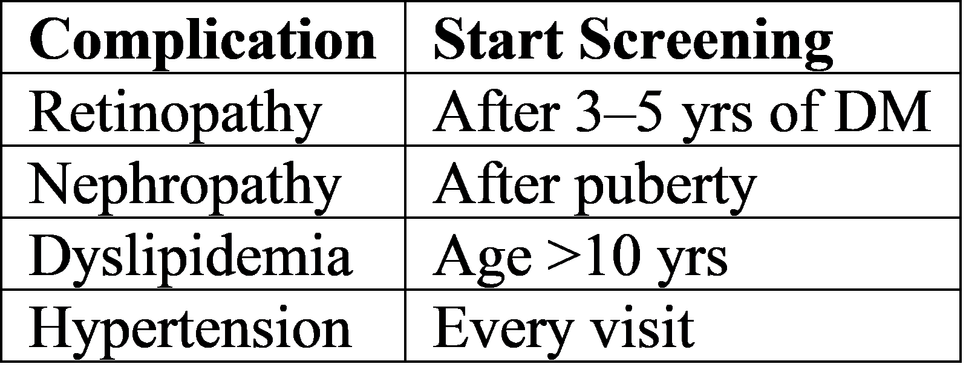

20. Screening and Follow-Up Protocols

Routine Screening Schedule

21. Recent Advances and Research

21.1 Immunotherapy

Teplizumab delays onset of T1DM in high-risk children

21.2 Artificial Pancreas Systems

Automated insulin delivery

Reduced glycemic variability

21.3 Stem Cell and Beta-Cell Replacement

Experimental but promising

22. Prognosis

With early diagnosis and optimal management:

Normal growth and development

Reduced complications

Near-normal life expectancy

Poor control leads to:

Early complications

Reduced quality of life

23. Conclusion

Diabetes mellitus in children is a lifelong condition requiring multidisciplinary care. Advances in insulin therapy, monitoring technologies, and education have dramatically improved outcomes. Early diagnosis, family support, psychological care, and public health strategies are critical to reducing morbidity and mortality. Prevention of type 2 diabetes through lifestyle interventions remains a major priority.

Reference

Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM.

Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 22nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2024.

Chapter: Diabetes Mellitus in Children and Adolescents.Sperling MA.

Pediatric Endocrinology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2020.

Chapter 14: Diabetes Mellitus.Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors.

Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000–.

Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine.

21st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2022.

Section: Diabetes Mellitus.

American Diabetes Association (ADA).

Children and Adolescents: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2024.

Diabetes Care. 2024;47(Suppl 1):S279–S301.

doi:10.2337/dc24-S014International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD).

ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022.

Pediatric Diabetes. 2022;23(Suppl 27):1–370.World Health Organization (WHO).

Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Geneva: WHO; 2019.

Mayer-Davis EJ, et al.

Incidence Trends of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes among Youths.

New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376:1419–1429.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1610187Patterson CC, et al.

Trends and Cycles in the Incidence of Childhood Type 1 Diabetes.

Diabetologia. 2019;62:408–417.

doi:10.1007/s00125-018-4763-3Dabelea D, et al.

Etiology and Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes in Youth.

Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1563–1573.