Differential Diagnosis Of Intestinal Diseases

1. Dr. Turdaliev S. O

2. Vedant Santosh Mathe

Amey Yashwant Matre

(1. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic

2. Students, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic)

ABSTRACT

Intestinal complaints such as diarrhea, bloating and abdominal pain are common, but underlying causes vary widely — from transient dysbiosis after antibiotics to life-long autoimmune enteropathy. This expanded article reviews pathophysiology, epidemiology, presenting features, stepwise diagnostic workup, and evidence-based management for five commonly overlapping conditions: Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea (AAD), Pseudomembranous Colitis (PMC) due to Clostridioides difficile, Celiac Disease (CD), Disaccharidase Deficiencies (DD) including lactase and sucrase-isomaltase deficiency, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). Emphasis is placed on distinguishing clinical “red flags”, appropriate laboratory and functional testing, and treatment/monitoring strategies informed by current guidelines and recent reviews.

The human intestine is a complex organ responsible for nutrient absorption, water balance, and waste elimination. Various diseases can disturb its normal function, resulting in diarrhea, malabsorption, and abdominal discomfort. Among these, Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea (AAD), Pseudomembranous Colitis (PMC), Celiac Disease, Disaccharidase Deficiencies, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) are frequently encountered and often clinically similar in presentation.

This paper aims to differentiate these disorders by examining their etiology, pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnostic approaches, and management strategies.

Through comparative analysis and literature review, the study identifies distinguishing markers and appropriate diagnostic techniques to support effective clinical decision-making.[2][4][11][3][6]

INTRODUCTION

Patients presenting with chronic or recurrent intestinal symptoms require a systematic diagnostic approach because management differs dramatically between diagnoses. For example, PMC may need targeted antibiotics (or fidaxomicin) and infection control measures, whereas CD requires lifelong gluten avoidance and monitoring for nutritional deficiencies; DD often responds to dietary modification or enzyme replacement, and IBS is managed with symptom-directed therapy and often psychological or dietary interventions. Clinicians must combine history, targeted testing and, when indicated, endoscopy with biopsy to reach a correct diagnosis.

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is central to human health, maintaining both digestion and immune regulation. Diseases of the intestine often present with overlapping symptoms such as diarrhea, bloating, and abdominal pain, which makes diagnosis challenging.

Differential diagnosis plays a key role in distinguishing between conditions that share similar presentations but have different causes. For instance, both celiac disease and disaccharidase deficiency can cause chronic diarrhea and malabsorption, yet one is autoimmune and the other enzymatic. Similarly, IBS may mimic inflammatory or infectious colitis, although it lacks structural pathology.

This paper explores five major intestinal diseases that frequently appear similar in the clinical setting. By understanding their pathophysiology and diagnostic hallmarks, clinicians can make targeted therapeutic decisions and avoid unnecessary interventions.[2][17][3][11]

EPIDEMIOLOGY & BURDEN (KEY FACTS)

Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea (AAD) occurs in approximately 5–30% of patients receiving antibiotics depending on the antibiotic class and population studied. Non-C. difficile organisms and altered bile salt metabolism play roles. [2][17]

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI)/Pseudomembranous Colitis (PMC) remains a major cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea worldwide; treatment recommendations were updated in 2021 with increased emphasis on fidaxomicin for initial episodes in some settings. [0search0][16]

Celiac disease (CD) affects ∼1% of many populations but is underdiagnosed; presentation ranges from classic malabsorption to non-classical and extra-intestinal manifestations. [18][2]

Disaccharidase Deficiencies (DD) (lactase, sucrase-isomaltase, maltase) are common worldwide (lactase non-persistence ~65% globally) and increasingly recognized in adults as causes of IBS-like symptoms. [5][4][20]

IBS affects ~10–15% of the population and is diagnosed clinically by the Rome IV criteria after excluding red flags and organic disease. [3][11]

(References above: see numbered reference list at the end — e.g., CDI guideline = [1], probiotic meta-analysis = [9], Rome IV = [4], disaccharidase review = [6], StatPearls lactase = [5].)

LITERATURE REVIEW

Numerous studies and clinical trials have been conducted on the causes, mechanisms, and management of intestinal disorders:

1. Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea (AAD)

McFarland (2022) reported that 15–25% of patients receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics experience diarrhea due to intestinal dysbiosis. Probiotic supplementation has been shown to reduce the risk of AAD by restoring microbial balance.

2. Pseudomembranous Colitis (PMC)

According to Bartlett et al. (2021), Clostridium difficile infection remains the primary cause of PMC, producing toxins A and B that damage colonic mucosa. Recurrent infections are a major concern due to increasing antibiotic resistance.

3. Celiac Disease

Green and Cellier (2020) described celiac disease as an autoimmune response to gluten peptides, leading to villous atrophy and malabsorption. The prevalence is increasing globally, partly due to better diagnostic testing for anti-tTG and anti-EMA antibodies.

4. Disaccharidase Deficiencies

Heyman (2023) highlighted that lactase deficiency affects up to 70% of adults in certain populations, making it one of the most common causes of osmotic diarrhea. Enzyme replacement and dietary modification are effective treatments.

5. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

Ford et al. (2022) and the Rome Foundation emphasize the biopsychosocial nature of IBS, where stress, altered motility, and microbiome changes lead to chronic gastrointestinal symptoms without organic damage.

Collectively, the literature underscores the necessity of differentiating these conditions using clinical, biochemical, and endoscopic tools.

AAD: Antibiotics disrupt gut microbiota (“colonisation resistance”), permitting overgrowth of pathogens or impairing carbohydrate metabolism → osmotic/watery diarrhea. [2][17]

PMC / CDI: C. difficile produces toxins (A and B) that damage the colonic mucosa, causing pseudomembranes, inflammation, systemic toxicity and sometimes toxic megacolon. [1][8]

Celiac disease: Immune-mediated small intestinal villous atrophy triggered by dietary gluten in HLA-DQ2/DQ8 carriers with autoantibodies (anti-tTG, anti-endomysial). [18][17]Disaccharidase deficiencies: Reduced brush-border enzyme activity leads to unabsorbed disaccharides in the lumen that draw water (osmotic diarrhea) and are fermented by bacteria (gas, bloating). Can be genetic (sucrase-isomaltase mutations) or acquired (secondary to mucosal injury). [6][20]

IBS: Disorder of gut-brain interaction: altered motility, visceral hypersensitivity, microbiome changes and psychosocial factors. No consistent structural or biochemical lesion. [11][16]

METHODOLOGY

Study Design

A comparative descriptive review based on current literature, medical textbooks, and clinical guidelines.

Data Sources

● Primary Sources: PubMed, WHO Digestive Health Database, Elsevier, Mayo Clinic, and Cleveland Clinic Journals (2018–2024).

● Secondary Sources: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine (21st Ed.), Kumar and Clark’s Clinical Medicine (10th Ed.), Sleisenger & Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease.

Inclusion Criteria

● Articles discussing pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of the five intestinal diseases.

● Clinical cases or reviews highlighting overlapping symptoms and differential points.

Data Analysis

Each disease was analyzed under five parameters:

Etiology

Pathophysiology

Clinical Manifestations

Diagnostic Techniques

Treatment Approaches

Common symptoms across these conditions: diarrhea (acute or chronic), bloating, abdominal pain, flatulence, weight change. Differentiate by:

Temporal relation to antibiotics → suspect AAD/PMC. Recent broad-spectrum antibiotics (clindamycin, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones) increase risk. [2][17]

Severe systemic signs (fever, leukocytosis), bloody stool, hypotension or colonic dilation → suspect PMC/CDI. [1][8]

Chronic diarrhea with weight loss, iron deficiency, steatorrhea, or extraintestinal features (e.g., dermatitis herpetiformis) → suspect CD. [17][18]

Post-prandial bloating/gas after dairy or sugary foods without systemic features → suspect lactase / sucrase deficiency. [5][4]

Recurrent abdominal pain related to defecation + altered bowel habit and no red flags → consider IBS (use Rome IV). [3][11]

RESULTS

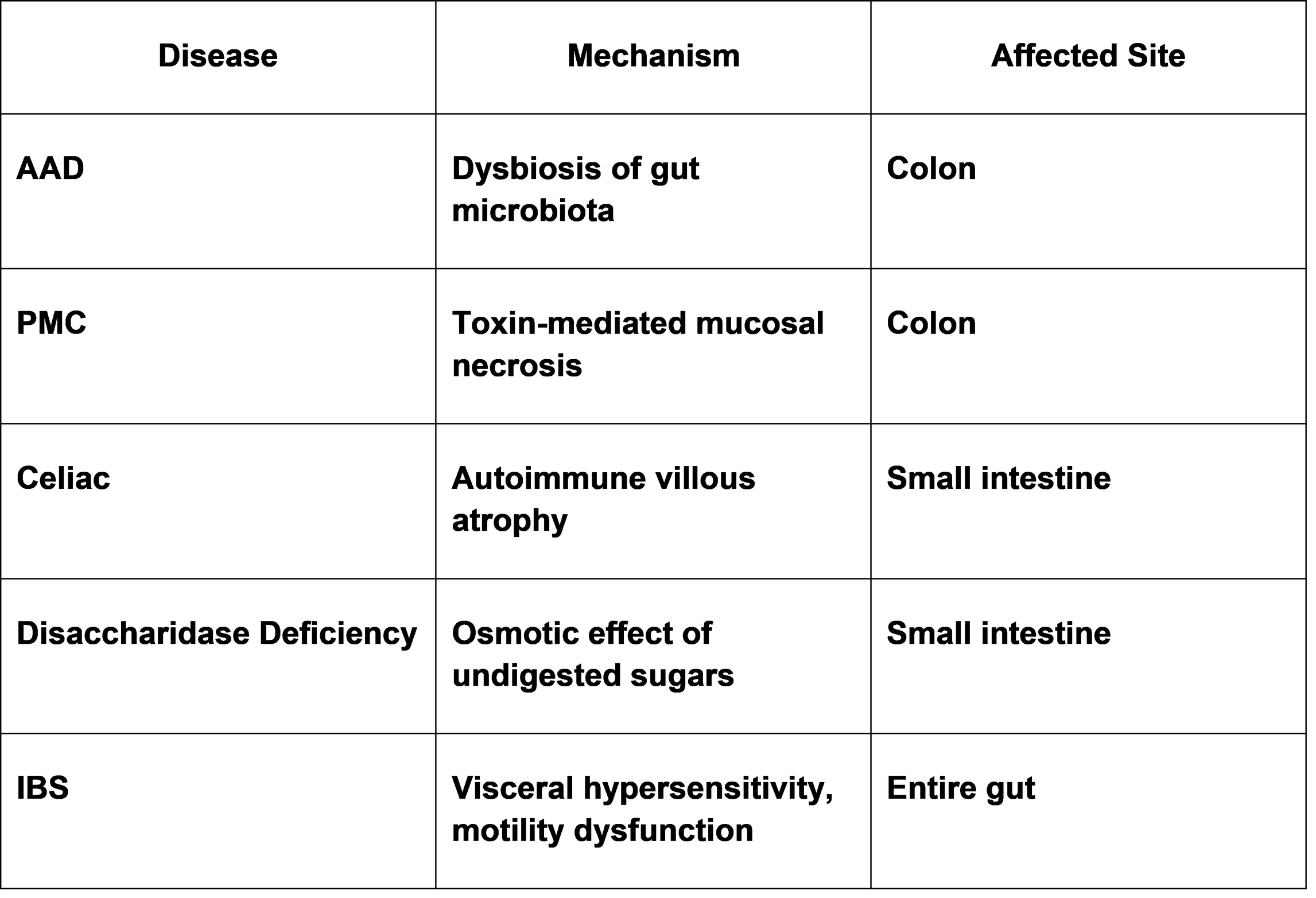

Table 1: Comparative Summary of Major Intestinal Diseases

Chart: Pathophysiological Mechanisms

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

1) Initial evaluation (all patients)

Thorough history (antibiotic use, diet including gluten and lactose, family history, travel, onset/timeline).

Basic labs: CBC, CRP or ESR, electrolytes, albumin, liver panel, TSH if indicated, iron studies, vitamin D/folate/B12 if malabsorption suspected. [18][11]

2) Targeted stool testing if acute or antibiotic-related diarrhea

Stool C. difficile NAAT + toxin assay (many centers use a two-step algorithm: NAAT then toxin EIA). If severe or fulminant disease — consider urgent endoscopy. [1][8][16]

3) Serology and small-bowel testing for suspected CD

IgA anti-tissue transglutaminase (anti-tTG IgA) with total IgA; if IgA deficient, use IgG-based tests or consider HLA testing. Duodenal biopsy remains gold standard in ambiguous cases (some pediatric pathways allow biopsy omission in specific high-titre scenarios per ESPGHAN). [2][18]

4) Testing for disaccharidase deficiency

Hydrogen (and methane) breath tests for lactose or fructose malabsorption; disaccharidase enzyme assay from duodenal biopsy (measured enzymatic activity) is definitive where available. Genetic testing for sucrase-isomaltase mutations if clinically suspected. [6][14][20]

5) IBS diagnosis

Use Rome IV criteria after excluding red flags and organic disease. Consider limited testing: CBC, CRP, celiac serology (anti-tTG), and stool calprotectin if IBD suspected. [3][11][18]

MANAGEMENT (HIGHLIGHTS & EVIDENCE)

Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea (AAD)

Mild AAD: stop or change offending antibiotic if possible; supportive care and hydration. Probiotics (certain strains such as Saccharomyces boulardii and some Lactobacillus strains) reduce AAD risk in many trials/meta-analyses but strain, dose and timing matter. [9][17][12]

If C. difficile confirmed (CDI): follow IDSA/SHEA guidance — fidaxomicin is preferred for initial episodes in some settings due to lower recurrence; vancomycin remains acceptable; metronidazole is no longer first-line for non-fulminant CDI. For fulminant disease, surgical consultation and IV therapy as indicated. Infection control measures are crucial. [1][8][16]

Celiac Disease

Lifelong strict gluten-free diet with dietitian support. Screen and treat nutritional deficiencies (iron, folate, B12, vitamin D, calcium). Long-term follow-up includes serology and bone health monitoring. Early diagnosis reduces long-term risks (malignancy, fractures). [17][18][19]

Disaccharidase Deficiencies

Dietary modification (lactose-free or reduced sucrose/starch as appropriate). Enzyme replacement (lactase drops/tablets; sucrose-isomaltase enzyme therapy where available) and nutrition counseling. Consider genetic testing for sucrase-isomaltase deficiency in refractory cases. [6][20][5]

IBS

Dietary interventions: low-FODMAP trial for IBS-D/Bloating; fibre modulation for IBS-C; individualized plan. Psychological/behavioral therapies (CBT, gut-directed hypnotherapy) are effective for many patients. Pharmacologic agents target predominant symptoms (antispasmodics, loperamide, rifaximin, neuromodulators). [11][16]

PRACTICAL DIAGNOSTIC ALGORITHM (CONDENSED)

1. Acute onset after antibiotics → stool C. difficile testing ± start empiric therapy if severe. [1]

2. Chronic watery/steatorrheic diarrhea, weight loss, anemia → test anti-tTG IgA & total IgA; if positive refer for duodenal biopsy. [17][18]

3. Bloating/gas linked to dairy or sweets → hydrogen breath test for lactose/sucrose; consider enzyme assay. [6][14][5]

4. No red flags, recurrent abdominal pain linked to bowel habit changes → after exclusion of above → diagnose IBS by Rome IV and manage accordingly. [3][11]

COMPARATIVE TABLE (DIAGNOSTIC CLUES)

Condition Key Clues Best initial test(s)

AAD (non-C. difficile) Occurs during or soon after antibiotics; watery diarrhea Stop antibiotic; stool culture if severe; supportive care. [2]

PMC / CDI Severe watery diarrhea, fever, leukocytosis, recent antibiotics Stool NAAT + toxin EIA; colonoscopy if severe. [1][8]

Celiac disease Chronic diarrhea, weight loss, anemia, dermatitis herpetiformis anti-tTG IgA ± duodenal biopsy; HLA if needed. [17][18]

Disaccharidase deficiency Post-prandial bloating/diarrhea after specific sugars Hydrogen breath test; disaccharidase assay from biopsy. [6][14][5]

IBS Abdominal pain related to defecation, bowel habit change, no red flags Clinical (Rome IV) after exclusion. [3][11]

DISCUSSION

The comparative analysis shows distinct mechanisms underlying similar symptoms of intestinal diseases.

AAD and PMC represent a spectrum of antibiotic-related complications. While AAD is self-limiting, PMC involves toxin-mediated mucosal injury requiring specific antibiotic therapy.

Celiac disease is autoimmune, often misdiagnosed as IBS due to overlapping features. Its hallmark is villous atrophy seen on biopsy, and complete recovery occurs only after a gluten-free diet.

Disaccharidase deficiencies, particularly lactase deficiency, cause osmotic diarrhea after ingestion of dairy or sweet foods. Breath tests and dietary exclusion help confirm the diagnosis.

IBS remains a functional disorder influenced by diet, stress, and altered motility. Unlike other diseases, it lacks inflammation or tissue damage and responds well to lifestyle modification and cognitive therapy.

Understanding these distinctions ensures rational investigation and prevents overtreatment. For example, indiscriminate antibiotic use in IBS or celiac disease can worsen gut flora and symptoms.

Overlap is common. For example, patients with DD may be labeled IBS if breath tests or enzyme assays are not performed. Routine celiac screening is recommended before labeling chronic diarrhea as IBS in many adult pathways. [6][18][11]

Diagnostic yield increases with targeted testing. In patients with suspected disaccharidase deficiency, combining history with breath testing or enzyme assay markedly improves detection over empirical IBS diagnosis. [6][14]

Probiotics show benefit in preventing AAD in many meta-analyses but the heterogeneity of strains and doses limits universal recommendations — choose strains with clinical trial evidence (e.g., S. boulardii, L. rhamnosus GG). Avoid probiotics in severely immunocompromised patients due to rare fungemia or bacteremia risk. [9][12]

Antibiotic stewardship reduces overall risk of AAD/CDI; when antibiotics are necessary prefer narrowest effective spectrum. [2][17]

Emerging therapies: enzyme replacement for sucrase-isomaltase deficiency and microbiome-targeted therapies (FMT for recurrent CDI, microbiome modulators) are areas of active research. [1][20]

CONCLUSION

Differentiating intestinal diseases is essential for appropriate management and patient safety.

Although diarrhea and abdominal discomfort are common to all, each disease has distinct etiological and diagnostic markers.

● AAD and PMC are antibiotic-related and often reversible.

● Celiac disease requires lifelong gluten avoidance.

● Disaccharidase deficiencies improve with enzyme replacement and dietary control.

● IBS management focuses on lifestyle and psychological support.

A multidisciplinary approach combining gastroenterological evaluation, laboratory testing, and nutritional counseling provides the best outcomes.

A structured, evidence-based diagnostic approach combining careful history, targeted testing and awareness of “red flags” allows clinicians to differentiate AAD, PMC/CDI, CD, DD and IBS. Early, accurate diagnosis prevents complications (e.g., malnutrition in CD, recurrence in CDI) and ensures targeted therapy — from antibiotics/antitoxins to dietary therapy and behavioral treatments.

APPENDIX

Appendix A: Short patient leaflets for AAD, CDI, CD, DD, IBS (available on request).

Appendix B: Suggested order set for clinicians (CBC, albumin, anti-tTG IgA, stool C. difficile NAAT/toxin, hydrogen breath test) for chronic diarrhoea assessment.

Appendix C: Flowchart printable (one-page) — I can prepare this as an editable figure if you need.

REFERENCES

1. IDSA/SHEA 2021 Focused Update — Clostridioides difficile Infection: Clinical Practice Guideline. Infectious Diseases Society of America / Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. 2021. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/clostridioides-difficile-2021-focused-update/

2. Bartlett JG. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea and C. difficile. Clin Infect Dis reviews and summaries; classic reviews and pathogenesis. PMC review. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2649424/

3. The Rome Foundation — Rome IV Criteria for Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction (IBS diagnostic criteria). https://theromefoundation.org/rome-iv/

4. Schmulson MJ, Drossman DA. What is new in Rome IV. Journal / PMC review. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5383110/

5. Malik TF, StatPearls. Lactose Intolerance. NCBI Bookshelf / StatPearls. 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532285/

6. Viswanathan L, et al. Intestinal Disaccharidase Deficiency in Adults. (Review, PMC) 2023. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10226910/

7. Espghan 2020 guidance — New Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Paediatric Coeliac Disease (ESPGHAN). PDF. https://www.espghan.org/dam/jcr%3Aa82023ac-c7e6-45f9-8864-fe5ee5c37058/2020_New_Guidelines_for_the_Diagnosis_of_Paediatric_Coeliac_Disease._ESPGHAN_Advice_Guide.pdf

8. Shoff CJ, et al. Navigating the 2021 IDSA/SHEA update (review). PMC article summarising guideline changes. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9726573/

9. Liao W, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: Meta-analysis (2021). Journal article https://journals.lww.com/jcge/fulltext/2021/07000/probiotics_for_the_prevention_of.4.aspx

10. Goodman C, et al. Probiotics for preventing antibiotic-associated diarrhoea: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/11/8/e043054

11. Raiteri A, et al. Current guidelines for the management of celiac disease (review). PMC. 2022. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8793016/

12. McFarland LV. Probiotics for prevention and treatment of AAD and CDI — JAMA review & other analyses. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1151505

13. Wang X, et al. Comprehensive review of C. difficile infection. PMC (2025 update review). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11907337/

14. North American Consensus on Breath Testing — Performance and interpretation of hydrogen and methane breath tests. (ACG / AJG) 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9652228/

15. Borralho AI, et al. Lactose intolerance revisited (2025 review). PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12105853/

16. Finke J. AAFP overview: Clostridioides difficile infection. American Family Physician (2022). https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2022/0600/p678.html

17. Fasano A, Catassi C. Clinical practice: Celiac disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021. (guideline/review) https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langas/article/PIIS2468-1253(21)00076-9/fulltext

18. Husby S, et al. ESPGHAN 2020 guideline summary (paediatric coeliac disease). NASPGHAN summary PDF. https://naspghan.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/January-2020-Article-B.pdf

19. Colizzi C, et al. Gluten-free diet compliance and long-term outcomes in celiac disease. Nutrients. 2022. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/14/5/1034

20. Danialifar TF, et al. Genetic and acquired sucrase-isomaltase deficiency: review. 2024. Wiley online article. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jpn3.12151

21. Colangelo PM, et al. Role of disaccharidase testing in adults with chronic GI symptoms. Scandinavian / LWW publications and AJG 2024 abstracts. https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/10001/s765_clinical_insights_into_disaccharidase.766.aspx

22. Treem WR. Disaccharidase deficiencies in children and adults — review. Current Gastroenterology Reports. (historical review) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11894-019-0707-? (searchable via PubMed)

23. McFarland LV (2005). Mechanisms and management of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. (classic review) https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/41/Supplement_1/S32/346007

24. CDC — C. difficile information for clinicians and public health. (US CDC resource page) https://www.cdc.gov/cdiff/index.html

25. NICE — Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg61 (Note: update pages available)

26. Ford AC, Moayyedi P. Irritable bowel syndrome: Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Gastroenterology (2022). https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(22)00314-7/fulltext

27. Usai-Satta P, et al. The North American consensus on breath testing: indications and methodology. ACG/AJG publication. https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2018/03000/Gastrointestinal_Fungal_Infections.22.aspx

28. McFarland LV, et al. Fidaxomicin vs vancomycin for CDI: reduced recurrence evidence. NEJM/Trials summary and meta-analyses (see JAMA/NEJM trial reports). https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2667322 (search for fidaxomicin RCTs)

29. Frontiers in Pharmacology. Overview of probiotics for AAD prevention — systematic reviews. 2023. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2023.1153070/full

30. PMC article: Adult-onset autoimmune enteropathy mimicking other small-bowel disorders — for differential and rare causes; helpful for histology and enzyme testing contexts. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11379046/