Global Analysis of Priority Occupational Diseases and Reasonable Accommodations for Vulnerable Workers

1. Dr. Turusbekova Akshoola Kozmanbetovna

2. Aryan Patial

(Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh state university, Kyrgyzstan

Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Kyrgyzstan)

Abstract

This comprehensive research report evaluates the critical intersection of occupational health and worker vulnerability, specifically focusing on pregnant, adolescent, older, and migrant populations. Through a systematic analysis of global occupational safety and health (OSH) frameworks, literature appraisal, and hazard identification, the study delineates the priority diseases and injuries disproportionately affecting these cohorts. The report maps these findings against the International Labour Organization (ILO) standards, including the Occupational Safety and Health Convention (No. 155) and the List of Occupational Diseases (Recommendation No. 194). Key findings highlight the prevalence of "3D" jobs (dirty, dangerous, and demanding) among migrants, developmental risks for adolescents, and the physiological and discriminatory barriers faced by pregnant and older workers. The analysis concludes that reasonable accommodations—ranging from ergonomic redesign and language-accessible training to flexible organizational structures—are essential for aligning workplace practices with international human rights and OSH mandates.

Keywords: Occupational Safety and Health (OSH), Vulnerable Workers, ILO Standards, Migrant Labor, Pregnant Workers, Adolescent Health, Aging Workforce, Reasonable Accommodations, Recommendation No. 194.

Introduction: Theoretical Foundations of Occupational Vulnerability

The global landscape of labor is increasingly defined by the participation of demographic groups that fall outside the traditional profile of the "standard" worker. These vulnerable populations—pregnant women, adolescents, older individuals, and migrant laborers—face unique health trajectories dictated by the interaction between their physiological profiles and the socio-economic conditions of their employment.1 Occupational safety and health (OSH) is fundamentally a component of "decent work," yet for these cohorts, decent work deficits are frequent, often manifesting as exposure to hazardous environments, lack of social protection, and systemic discrimination.1

The International Labour Organization (ILO) provides the primary normative framework for addressing these disparities. Since its inception in 1919, the ILO has utilized Conventions and Recommendations to establish international treaties and guiding principles that bind member States to specific health and safety outcomes.4 The significance of these standards lies in their practical application: they reflect feasible social progress while pointing toward a future where the workplace is inherently a site of health promotion rather than hazard exposure.4 However, the reality for many of the world's 164 million migrant workers and other vulnerable groups is a persistent exposure to risks that lead to a higher incidence of occupational injuries and work-related diseases compared to their non-vulnerable peers.1

This report adopts a rigorous approach to identifying priority occupational diseases, critically appraising existing literature, and mapping hazards to the latest ILO standards. By examining the origin, mechanism, and future outlook of these health risks, the analysis provides a strategic framework for implementing reasonable accommodations that preserve the health, safety, and dignity of the most exposed members of the global workforce.

Section 1: Literature Search and Methodological Critical Appraisal

Evaluating the Quality of Occupational Health Research

A critical appraisal of the available literature on vulnerable workers reveals significant heterogeneity in study design and data quality. Occupational health literature frequently fails to adequately distinguish the specific characteristics of migrant groups, such as their legal status, language proficiency, or previous work experience, which are essential confounders for health outcomes.7 Most existing research is concentrated in middle- and high-income regions, leaving a substantial gap in the understanding of risks in developing economies where informal sectors and loose regulations are more prevalent.8

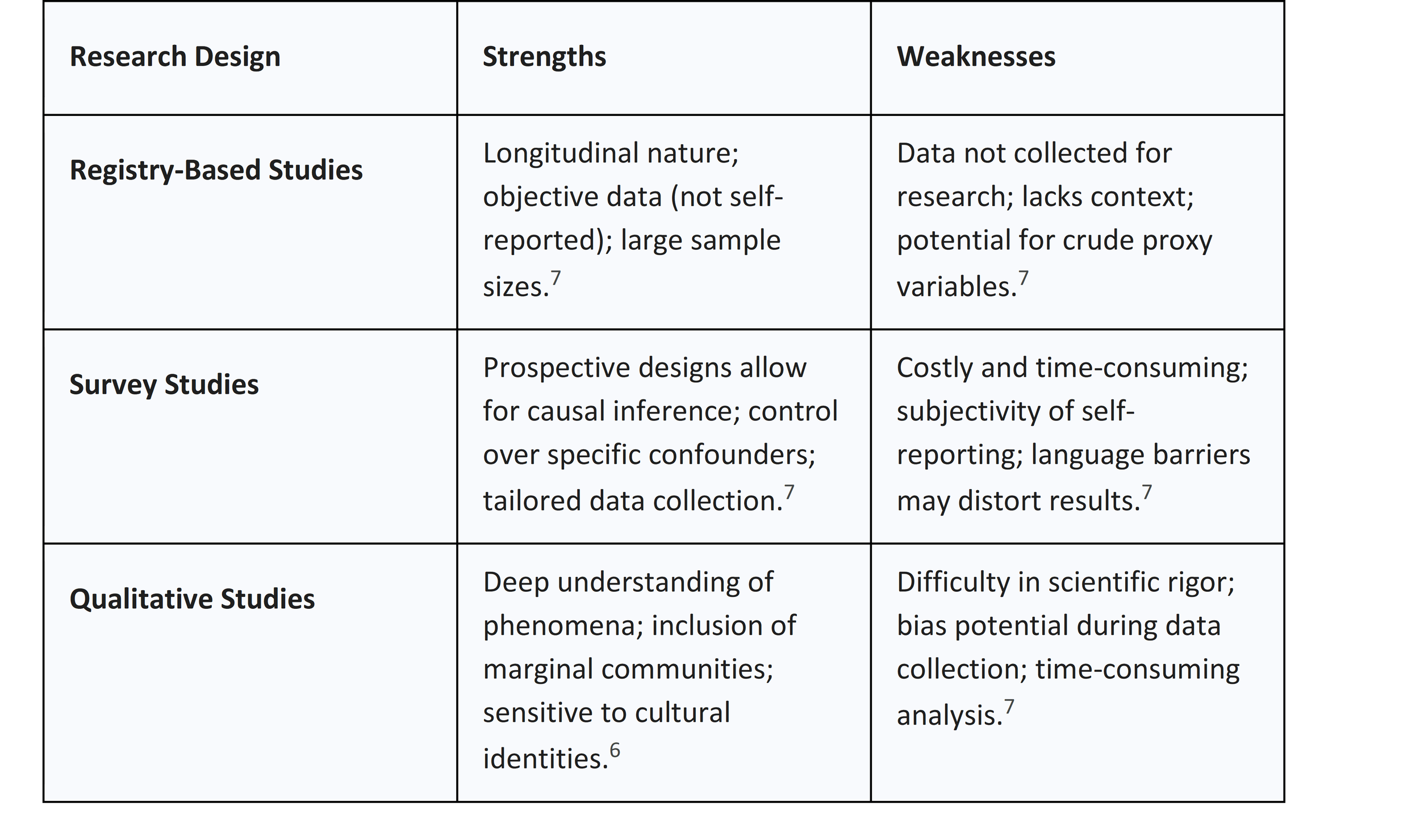

When assessing the health of vulnerable workers, researchers utilize several methodological approaches, each with inherent strengths and weaknesses that must be considered when formulating policy.

The lack of reliable data is particularly acute regarding occupational diseases among migrants. While fatal injury statistics are frequently compiled, work-related diseases—which kill six times more people than injuries globally—remain systematically under-reported and under-documented.8 This deficit in reporting is often due to the long latency periods of occupational diseases and the multifactorial nature of their genesis, which complicates the establishment of a direct causal link to a specific workplace.6

The Expert System for Identification of Occupational Diseases

To bridge the gap between exposure and diagnosis, the ILO proposes an "Expert System" for identifying occupational diseases in vulnerable populations.10 This methodology utilizes an algorithm that integrates four primary vectors:

1. Industry and Occupation Identification: Establishing the specific tasks and environmental conditions of the worker's role.

2. Exposure Estimation: Quantifying the frequency, duration, and magnitude of exposure to physical, chemical, or biological agents.

3. Clinical Evidence: Recording symptoms and utilizing specialized tests, such as pulmonary function tests or enzyme level analysis.

4. Confounder Management: Accounting for non-occupational factors, such as family history or lifestyle choices, to confirm the occupational origin of the morbidity.

This structured approach is vital for groups like adolescent and migrant workers, who may not have a documented history of exposure or who may be unfamiliar with the clinical manifestations of the hazards they face.10

Section 2: Priority Occupational Diseases in Migrant Workers

The "3D" Job Phenomenon and Health Disparities

Migrant workers represent a vital yet highly exposed 4.7% of the global workforce.8 They are disproportionately represented in sectors characterized by "3D" jobs: dirty, dangerous, and demanding.6 These occupations, which include agriculture, construction, mining, manufacturing, and domestic work, inherently expose workers to higher environmental hazards and precarious employment conditions.8

Epidemiological evidence indicates that migrants face a significantly higher risk of both fatal and non-fatal injuries compared to native-born workers. In 73% of countries where data is available, fatal occupational injury rates are higher for migrants.6 This is not merely a product of the sector but also of the social determinants of health, such as language barriers, cultural isolation, and the tendency to take higher risks due to precarious economic status.6

Mapping Priority Diseases for Migrants

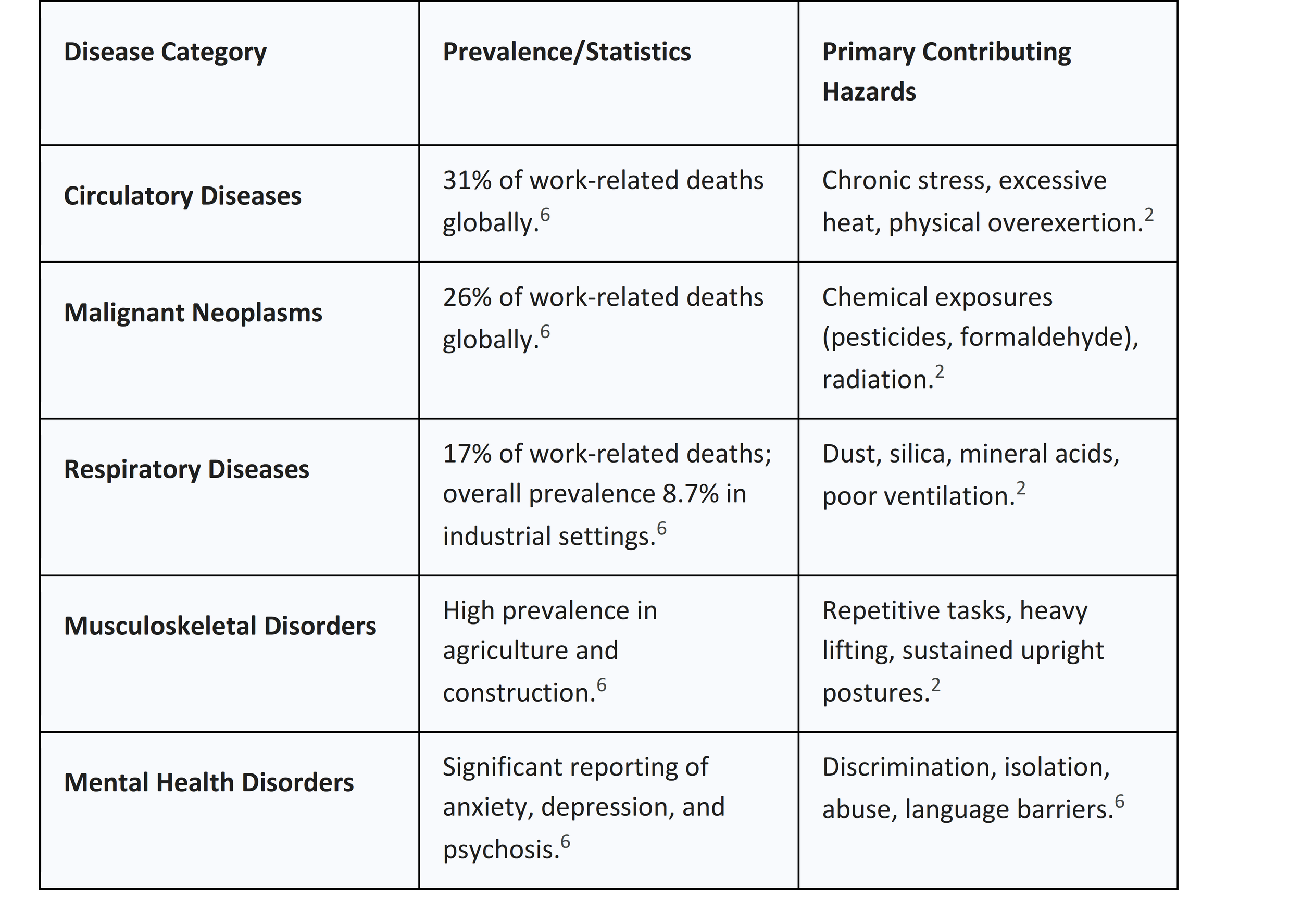

According to the latest ILO estimates, over 75% of work-related deaths are attributed to chronic diseases rather than acute accidents.6 For migrant populations, these diseases are often exacerbated by their living and working conditions.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic underscored the vulnerability of migrant workers, who faced high rates of infection due to work organization that made social distancing difficult and living conditions that facilitated viral transmission.6 Furthermore, migrants often have less access to the specialized occupational health services necessary for the early detection of these non-communicable diseases (NCDs).2

Reasonable Accommodations and ILO Mapping for Migrants

Protection for migrant workers is anchored in the Migration for Employment Convention (Revised), 1949 (No. 97) and the Migrant Workers (Supplementary Provisions) Convention, 1975 (No. 143).1 These standards mandate that migrants receive treatment no less favorable than that of nationals, particularly regarding OSH.1

1. Language and Communication Accommodations

One of the most frequent challenges in promoting safety for migrants is the language barrier.9 Effective accommodations must move beyond simple translation.

● Native Language Training: Safety protocols and hazard recognition should be taught in the learner's native language using visual-heavy materials, infographics, and hands-on demonstrations.9

● Bilingual Supervision: Organizations should intentionally hire bilingual supervisors who possess the technical knowledge and cultural competence to lead diverse teams effectively.9

● Interactive Process: Employers should engage in a dialogue with workers to identify where language gaps might exist and verify comprehension using "teach-back" methods.13

2. Housing and Living Standards

For many migrants, the workplace and living facilities are inextricably linked. The ILO provides specific guidance for migrant housing to ensure health is not compromised outside of work hours.24

● Space and Privacy: Sleeping spaces should be at least 198 cm by 80 cm, with headroom not less than 203 cm to allow free movement.24

● Environmental Health: Facilities must be equipped with adequate ventilation, heating, and lighting, and be protected from pests and natural hazards like flooding.24

● Hygiene: A minimum of one toilet, washbasin, and shower for every six persons must be provided, with separate facilities for men and women.24

Section 3: Pregnant and Breastfeeding Workers - Reproductive OSH

Physiological Vulnerability and Obstetric Complications

The occupation of a woman during pregnancy can have profound impacts on fetal development and maternal well-being.25 Pregnant workers are exposed to a range of hazards that can lead to adverse reproductive outcomes, including miscarriage, preterm birth, and low birth weight.26 The literature suggests that lifestyle factors, while significant, are often overshadowed by occupational demands such as prolonged standing, heavy lifting, and exposure to hazardous substances.25

A study involving nearly 50,000 pregnant women found that those in high-stress jobs had a higher prevalence of preterm birth, while night shift work (more than two shifts a week) was associated with a 32% increased risk of miscarriage after the eighth week of pregnancy.26 Furthermore, the lack of ergonomic modifications can lead to hypertensive disorders and gestational diabetes, which put both the mother and child at life-threatening risk.25

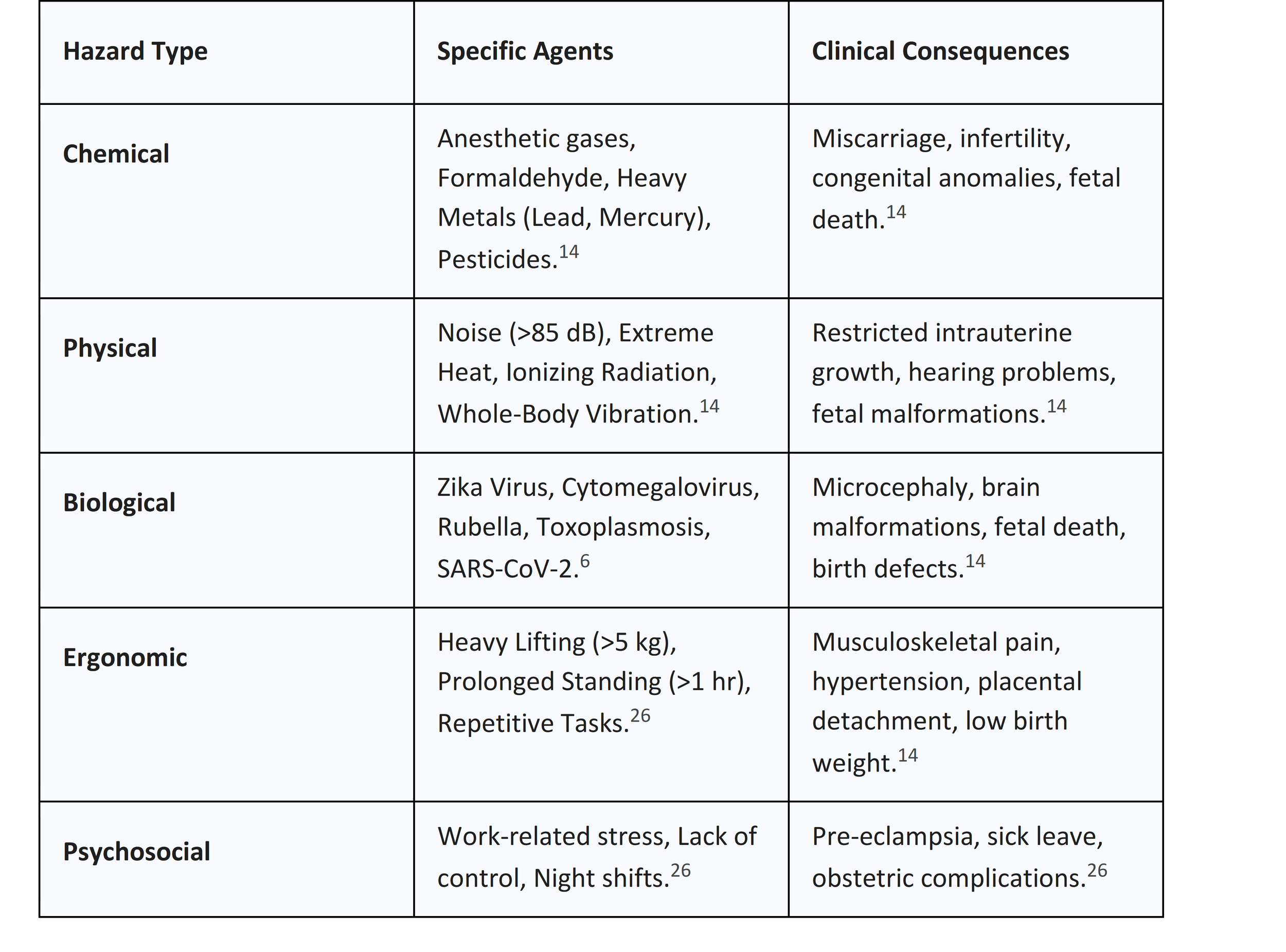

Priority Hazards for Pregnant Workers

The identification of hazards for this cohort must be exhaustive, as even common workplace agents can be teratogenic or harmful to the nursing infant.14

The "triple discrimination" of being a woman, a migrant, and pregnant creates a particularly precarious situation in global supply chains. In some regions, such as Malaysia, pregnant migrant workers face mandatory testing and automatic deportation, which forces women to choose between their maternal rights and their livelihood.29

Reasonable Accommodations Aligned with Global Standards

The ILO framework, including the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) and the List of Occupational Diseases Recommendation (No. 194), provides the basis for national laws like the U.S. Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (PWFA).30 These standards require that employers provide accommodations for "known limitations" unless they cause an "undue hardship".31

1. Physical and Task Modifications

● Stationary Support: Providing a stool for pregnant cashiers or assembly workers to alleviate leg pain and swelling from prolonged standing.32

● Lifting Restrictions: Reassigning heavy lifting tasks to other team members or using mechanical aids to prevent physical strain.32

● Environment Relocation: Moving the pregnant worker away from high-heat areas or workstations where hazardous chemicals (e.g., formaldehyde or anesthetic gases) are used.14

2. Organizational and Scheduling Accommodations

● Flexible Breaks: Allowing additional or longer breaks for hydration, nutrition, and restroom use, which are "virtually always reasonable" and rarely pose an undue hardship.32

● Health Care Access: Modifying schedules to allow for prenatal medical appointments, postpartum depression therapy, or lactation-related needs.32

● Telework and Reduced Hours: Offering remote work options or shorter shifts to manage the fatigue associated with later stages of pregnancy.25

3. Lactation Support

Under the PUMP for Nursing Mothers Act, employers must provide reasonable break time and a private, non-bathroom space for employees to express breast milk for up to one year after the child's birth.31

Section 4: Adolescent Workers - Protecting the Developing Body

Developmental Risks and the Gap Between Law and Practice

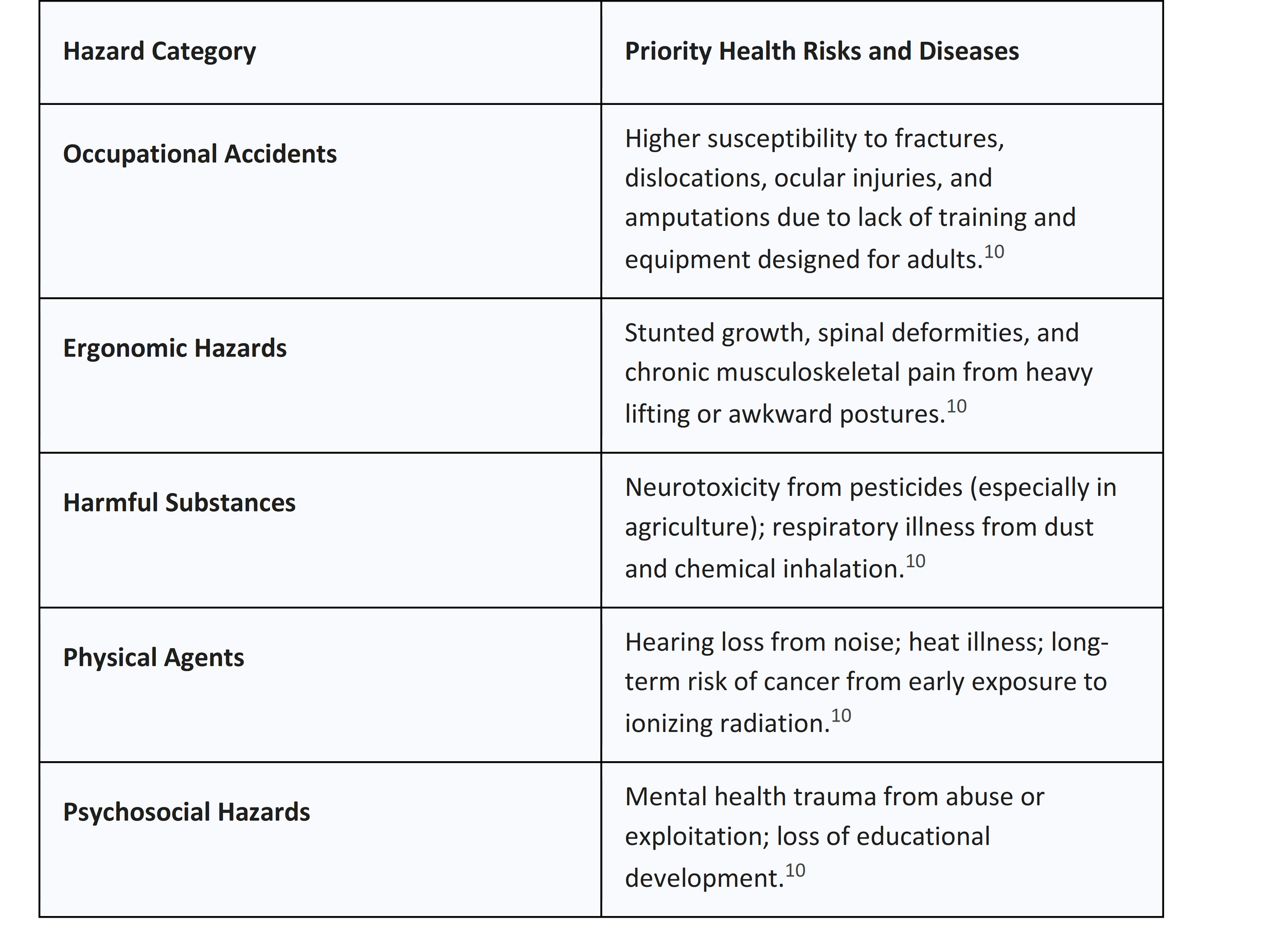

Adolescent workers are in a state of rapid biological and cognitive development, making them more susceptible to workplace hazards than adults.10 Their musculoskeletal systems are not yet fully ossified, their metabolic rates are higher (leading to increased absorption of toxins), and their relative lack of experience means they are less likely to recognize danger or question unsafe practices.10

The ILO distinguishes between "child labor," which should be abolished, and "youth employment," where adolescents above the minimum working age (typically 15) are engaged in decent work.36 However, a significant "gap between law and practice" exists; many adolescents remain trapped in hazardous work, which is defined as any labor that by its nature or circumstances is likely to harm the health, safety, or morals of children.10

Priority Hazards and Diseases for Adolescents

Exposure to physical and chemical agents during adolescence can have life-long metabolic and pulmonary consequences.10

The "triple discrimination" of being a woman, a migrant, and pregnant creates a particularly precarious situation in global supply chains. In some regions, such as Malaysia, pregnant migrant workers face mandatory testing and automatic deportation, which forces women to choose between their maternal rights and their livelihood.29

Reasonable Accommodations Aligned with Global Standards

The ILO framework, including the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) and the List of Occupational Diseases Recommendation (No. 194), provides the basis for national laws like the U.S. Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (PWFA).30 These standards require that employers provide accommodations for "known limitations" unless they cause an "undue hardship".31

1. Physical and Task Modifications

● Stationary Support: Providing a stool for pregnant cashiers or assembly workers to alleviate leg pain and swelling from prolonged standing.32

● Lifting Restrictions: Reassigning heavy lifting tasks to other team members or using mechanical aids to prevent physical strain.32

● Environment Relocation: Moving the pregnant worker away from high-heat areas or workstations where hazardous chemicals (e.g., formaldehyde or anesthetic gases) are used.14

2. Organizational and Scheduling Accommodations

● Flexible Breaks: Allowing additional or longer breaks for hydration, nutrition, and restroom use, which are "virtually always reasonable" and rarely pose an undue hardship.32

● Health Care Access: Modifying schedules to allow for prenatal medical appointments, postpartum depression therapy, or lactation-related needs.32

● Telework and Reduced Hours: Offering remote work options or shorter shifts to manage the fatigue associated with later stages of pregnancy.25

3. Lactation Support

Under the PUMP for Nursing Mothers Act, employers must provide reasonable break time and a private, non-bathroom space for employees to express breast milk for up to one year after the child's birth.31

Section 4: Adolescent Workers - Protecting the Developing Body

Developmental Risks and the Gap Between Law and Practice

Adolescent workers are in a state of rapid biological and cognitive development, making them more susceptible to workplace hazards than adults.10 Their musculoskeletal systems are not yet fully ossified, their metabolic rates are higher (leading to increased absorption of toxins), and their relative lack of experience means they are less likely to recognize danger or question unsafe practices.10

The ILO distinguishes between "child labor," which should be abolished, and "youth employment," where adolescents above the minimum working age (typically 15) are engaged in decent work.36 However, a significant "gap between law and practice" exists; many adolescents remain trapped in hazardous work, which is defined as any labor that by its nature or circumstances is likely to harm the health, safety, or morals of children.10

Priority Hazards and Diseases for Adolescents

Exposure to physical and chemical agents during adolescence can have life-long metabolic and pulmonary consequences.10

ILO Standards Mapping: C138 and C182

The Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (No. 138) and the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182) form the foundation of global protection.36 Convention No. 182, which has achieved universal ratification, requires immediate action to eliminate work in confined spaces, underground, or with dangerous machinery for anyone under 18.36

Reasonable Accommodations and Supervisory Models

For adolescents in legal employment, the focus must shift from mere compliance to active mentorship and protection.38

1. Supervision and Mentorship

● Buddy System: Pairing young workers with experienced mentors who can provide real-time feedback and model safe practices.11

● First-Line Oversight: Supervisors must be specifically trained to understand adolescent psychology—recognizing that teens may be reluctant to admit they don't understand instructions.11

● Visual Identifiers: Issuing different-colored smocks or badges to workers under 18 to ensure they are not assigned to prohibited tasks, such as operating power-driven meat slicers or industrial mixers.41

2. Hazard Recognition and Training

● Hands-on Training: Providing "hands-on" safety training that covers hazard recognition and proper equipment use in short, periodic sessions rather than one long class.11

● Emergency Preparedness: Training adolescents on escape routes and emergency response for fires, accidents, or violent situations, ensuring they know exactly where to go and whom to tell if they are injured.11

● Equipment Inspection: Labeling all machinery that is legally off-limits to young workers and ensuring that personal protective equipment (PPE) like goggles and gloves are properly sized for their smaller frames.11

Section 5: Older Workers - Sustaining an Aging Workforce

The Physiological Challenges of Aging in the Workplace

As the global population ages, older workers (those whose difficulties in employment arise from advancing age) are required to stay in the workforce longer.42 While aging is a heterogeneous process, it is often accompanied by a decline in muscle mass, sensory acuity (hearing and vision), and a decreased ability to recover from physical strain or injury.42

Older workers are particularly vulnerable to chronic occupational diseases with long latency periods, such as noise-induced hearing loss, respiratory diseases from long-term dust exposure, and work-related cancers.2 Furthermore, age discrimination is increasingly recognized as an occupational health issue, as it leads to social isolation, psychological stress, and reduced access to vocational training.42

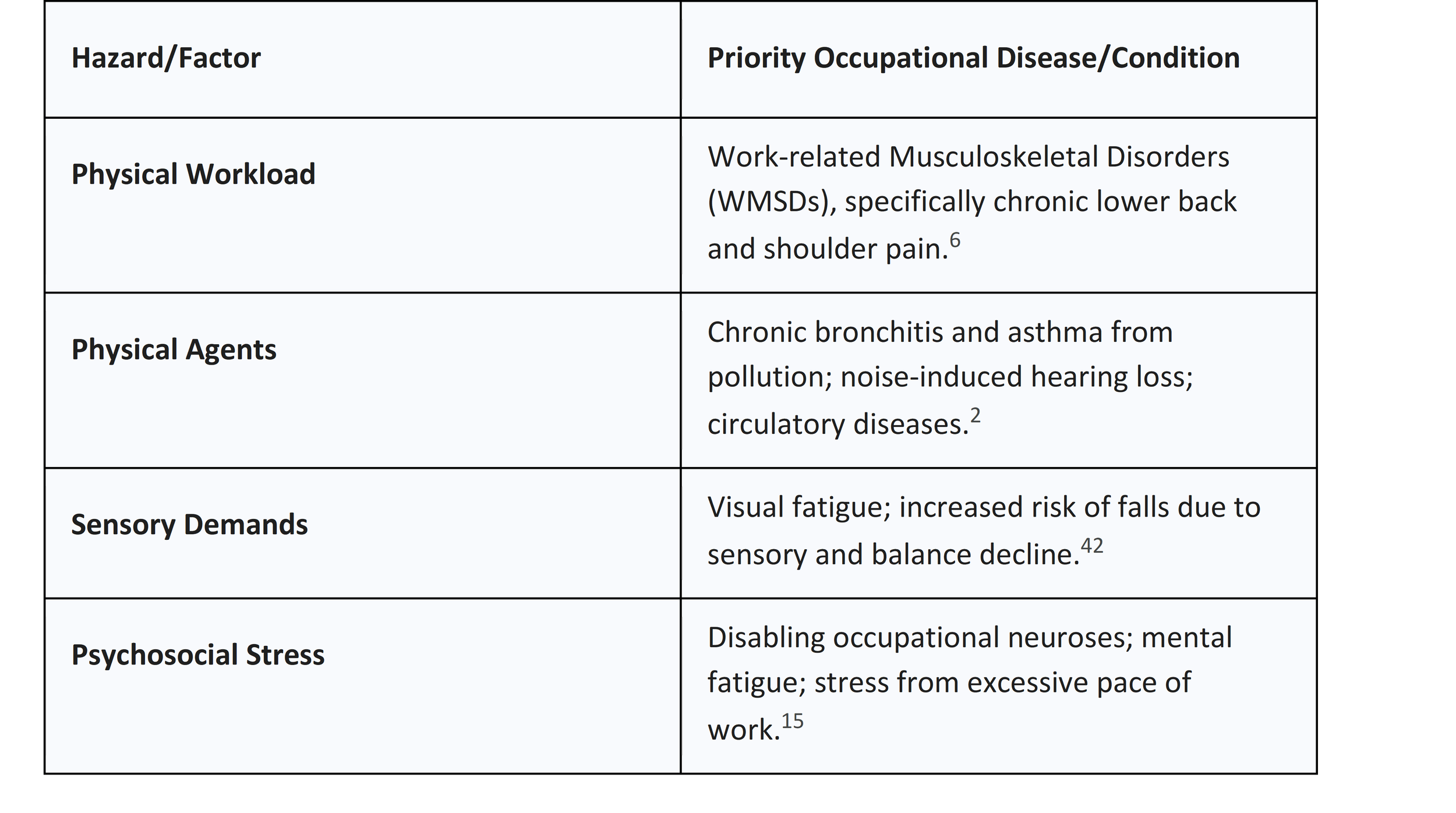

Priority Hazards and Diseases for Older Workers

The "hastening of the aging process" occurs when workers are kept in arduous, hazardous, or unhealthy conditions for extended periods.42

In some countries, blue-collar workers are at a distinct disadvantage; their roles require more physical power, and as they age, they are viewed as less productive and more prone to accidents, leading to systemic exclusion.44

Reasonable Accommodations and ILO R162 Mapping

The Older Workers Recommendation, 1980 (No. 162) provides the most direct guidance on protecting this demographic.21 It calls for national policies to promote equality of treatment and modify work environments to suit the aging process.42

1. Ergonomic and Environmental Adaptation

● Job Content Modification: Adapting the job to the worker through all available technical means, such as providing lifting aids, elevators, and increased lighting to compensate for sensory decline.42

● Remedying Conditions: Improving work environments that are likely to hasten aging, such as extreme temperatures or high-vibration tasks.42

● Health Supervision: Implementing systematic medical surveillance to detect occupational diseases early and providing health education on medical examinations, diet, and exercise.42

2. Organization of Working Time

● Hours Reduction: Reducing the normal daily and weekly hours of work for those in arduous or hazardous roles as they approach retirement.42

● Flexible Scheduling: Providing flexible working hours or part-time employment options to help workers manage their health needs and non-work demands.42

● Shift Transition: Facilitating the transfer of older workers from night shifts or continuous shift work to normal daytime hours to reduce physiological stress.42

3. Remuneration and Security

● Payment Systems: Moving away from "pay by results" (which prioritizes speed) to "pay by time" or systems that value know-how and experience.42

● Retraining: Providing access to vocational training and retraining for different industries if their current sector is in decline or becoming too physically demanding.42

Section 6: The ILO List of Occupational Diseases (R194) and Evolution of Standards

Identification and Recognition Criteria

The List of Occupational Diseases Recommendation, 2002 (No. 194), and its subsequent 2010 revision, represent the international consensus on diseases caused by work.30 For a disease to be incorporated into this list, experts look for a causal relationship with a specific agent or work process and a prevalence rate among exposed workers that is higher than in the general population.45

A critical feature of R194 is the inclusion of "open items" in every section. These allow for the recognition of the occupational origin of diseases not explicitly named, provided a link can be established between exposure and the disorder.18 This is essential for vulnerable workers who may be exposed to emerging hazards or non-traditional agents.45

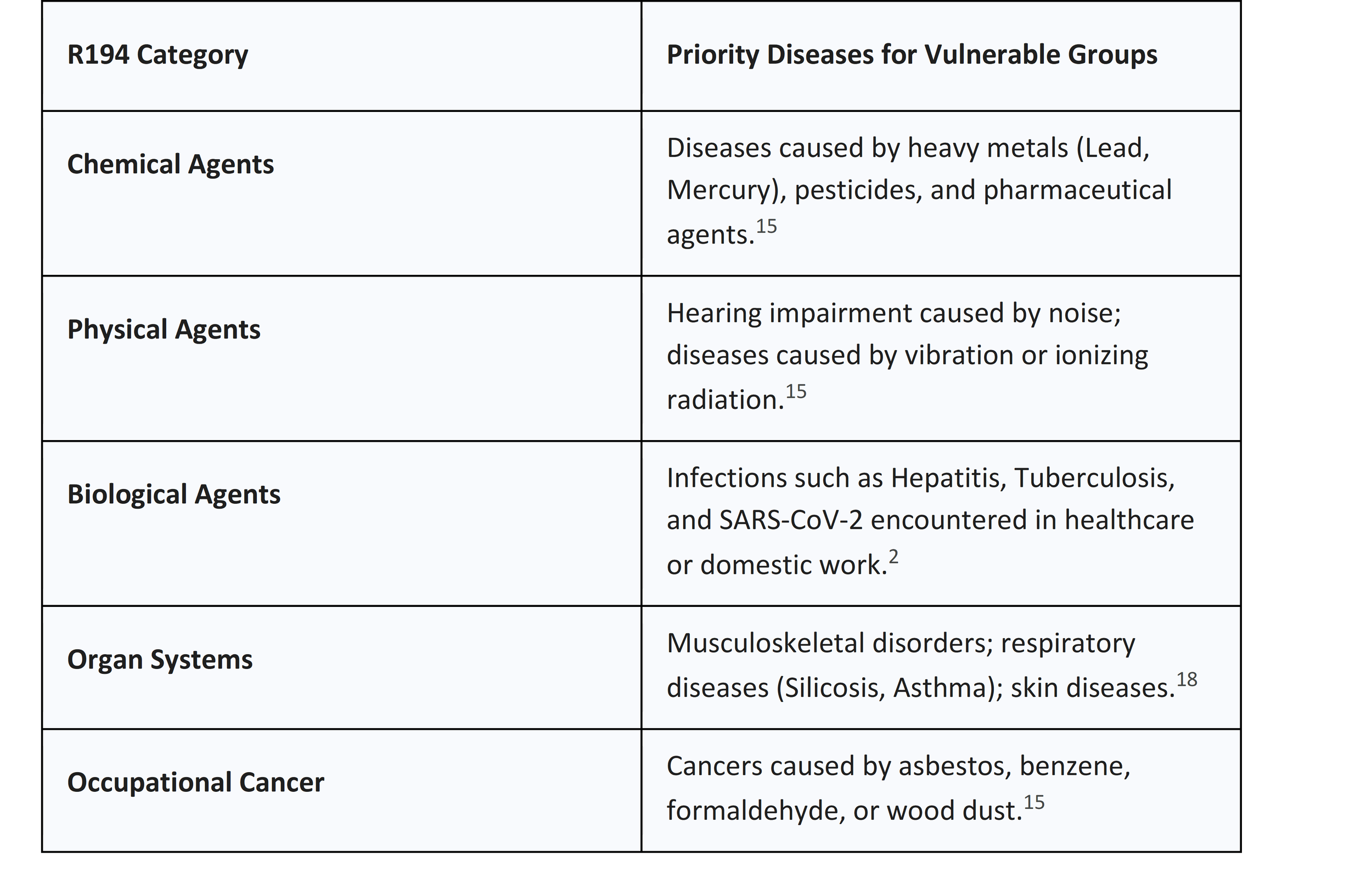

Key Agents and Diseases Relevant to Vulnerable Cohorts

The 2010 revision specifically added mental and behavioral disorders, such as psychosomatic syndromes caused by workplace mobbing, reflecting the modern psychosocial challenges faced by migrant and older workers.15

The evolution of this list has seen disagreements between tripartite stakeholders. For example, worker organizations successfully pushed for the addition of endocrine system diseases due to chemicals, while employer groups often advocated for more specific definitions of cancer to limit liability.15 For the vulnerable worker, this ongoing refinement ensures that the list remains a relevant tool for "prevention, recording, and compensation".18

Section 7: Strategic Framework for Implementing Inclusive OSH

Developing National OSH Systems

A sound OSH framework for vulnerable workers must be "comprehensive, prevention-based, and overarching".5 The ILO Support Kit for Developing OSH Legislation emphasizes that OSH laws should apply universally to all workers, including those in the informal sector, agriculture, and domestic work where vulnerable groups are most concentrated.5

Key components of an inclusive national OSH system include:

● Coordination and Cooperation: Establishing OSH institutions that can work across labor, health, and migration departments.5

● Labor Inspection: Strengthening the capacity of inspectors to identify "hidden" hazards in small enterprises and to communicate with migrant workers.3

● Primary Care Integration: Connecting occupational health services with primary care centers to facilitate the detection of common occupational diseases like chronic bronchitis or MSDs among those who lack specialized work-based services.2

Building an Organizational Culture of Prevention

For the employer, creating a safe environment for vulnerable workers requires an "institutional self-assessment" to ensure that "the way we do things here" does not inadvertently exclude or harm specific groups.9

1. Establishing Trust: Effective OSH communication begins with trust. Migrant and adolescent workers are often afraid of being fired or deported for reporting hazards.13 Employers must create an environment where "speaking up" is protected and valued.35

2. Interactive Process for Accommodations: When a worker has a limitation (due to pregnancy, age, or injury), the employer should engage in a dialogue to determine the most effective accommodation.33 This process is not about giving the worker exactly what they want, but finding a solution that addresses the limitation without causing undue hardship.32

3. Tailoring Safety Training: Training must move beyond translation to account for the diverse perspectives and education levels of the workforce.9 This includes recognizing that many immigrant workers take jobs in sectors they did not work in previously and may be unfamiliar with U.S. or European machine standards.9

Section 8: Future Outlook and Global Challenges

The future of occupational health for vulnerable workers faces several emerging challenges. The "Global Care Chain," where women migrate to provide care services for children and the elderly in wealthier countries, creates a new category of "migrant care workers" who often work in informal, isolated settings without basic labor rights.12 Additionally, the demographic shift toward an older workforce in many developed countries will require a permanent redesign of ergonomic standards to maintain productivity without compromising worker health.44

Global initiatives like the Global Compact for Migration and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 8.7 and 8.8) have renewed commitments to protect labor rights and promote safe working environments for all, with a specific focus on those in precarious employment.8 However, as the ILO estimates of 2.78 million annual work-related deaths suggest, the road to universal OSH coverage remains long.6

Conclusion

This analysis of priority occupational diseases among vulnerable workers demonstrates that health outcomes are as much a product of policy and organizational culture as they are of biological agents. Pregnant workers, adolescents, older workers, and migrants occupy the "front lines" of global production, often in the most hazardous and least regulated sectors. The priority diseases they face—ranging from acute injuries and respiratory failure to chronic stress and reproductive harm—are predictable and, most importantly, preventable.

The mapping of these hazards to ILO standards reveals a robust global framework that, when implemented, provides the necessary protections to ensure that vulnerability does not equate to injury. Reasonable accommodations are the practical expression of these standards; they are the bridge between a hazardous environment and a safe one. Whether it is providing a stool for a pregnant cashier, ensuring a migrant’s housing has adequate space, or pair-mentoring a young apprentice, these interventions preserve the most vital component of any economy: its people.

The imperative for the future is clear: we must improve the systematic collection of data on occupational diseases, bridge the gap between national legislation and international standards, and foster a global culture of prevention where every worker—regardless of their status, age, or physiological state—can return home healthy and safe.

References -

1. Safety and health for migrant workers | International Labour ..., accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/resource/safety-and-health-migrant-workers

2. Tool 12 Workers and occupational health and safety, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.who.int/tools/refugee-and-migrant-health-toolkit/module-3/tool-12

3. Occupational Safety and Health Statistics (OSH database) - ILOSTAT, accessed January 12, 2026, https://ilostat.ilo.org/methods/concepts-and-definitions/description-occupational-safety-and-health-statistics/

4. guide to labour standards international, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/media/330471/download

5. Support Kit for Developing Occupational Safety and Health Legislation - International Labour Organization, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/2024-12/SupportKitOSHLegislation.pdf

6. Occupational Health and Safety and Migrant Workers: Has Something Changed in the Last Few Years? - NIH, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9367908/

7. Migrant workers occupational health research: an OMEGA-NET working group position paper - PubMed Central, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8521506/

8. OCCUPATIONAL FATALITIES AMONG INTERNATIONAL MIGRANT WORKERS - IOM Publications, accessed January 12, 2026, https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/Occupational-Fatalities.pdf

9. Safety & the Diverse Workforce: Lessons From NIOSH's Work With ..., accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4641045/

10. CHILDREN - International Labour Organization, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/2025-06/Children%20at%20work%20-%20Health%20and%20safety%20risks%20-First%20edition.pdf

11. Employer Responsibilities for Keeping Young Workers Safe | Occupational Safety and Health Administration - OSHA, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.osha.gov/young-workers/employer-responsibilities

12. THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF MIGRANT CARE WORK At the intersection of care, migration and gender, accessed January 12, 2026, https://englishbulletin.adapt.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/wcms_674622.pdf

13. Why language matters for workplace safety and health - DOL - U.S. Department of Labor, accessed January 12, 2026, https://beta.dol.gov/news-events/blog/why-language-matters-workplace-safety-and-health

14. Occupational risk perceived by pregnant workers: proposal for an assessment tool for health professionals - NIH, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7732040/

15. Historical review of the List of Occupational Diseases recommended by the International Labour organization (ILO) - PMC, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3923370/

16. Prevalence of occupational respiratory disease and its determinants among workers in major industrial sectors in Malaysia in 2023 - NIH, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12267597/

17. ILO List of Occupational Diseases - International Labour Organization, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/media/336656/download

18. List of occupational diseases (revised 2010) - International Labour Organization, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/media/336021/download

19. Occupational health outcomes among international migrant workers ..., accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6565984/

20. Prevalence and correlation of workload and musculoskeletal disorders in industrial workers: a cross-sectional study - PubMed Central, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12500539/

21. Technical Note 4.4: Instruments concerning older workers - International Labour Organization, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/2024-08/16_TN%204-4%20-%20Older%20workers%20%289%20Aug%202024%29-EN.pdf

22. Safety Training is Most Effective in the Learner's Native Language - HSI, accessed January 12, 2026, https://hsi.com/blog/training-effective-native-language

23. Health + Safety Best Practices for Limited English Proficiency Employees - WorkCare, accessed January 12, 2026, https://workcare.com/resources/blog/health-safety-best-practices-for-limited-english-proficiency-employees/

24. MIGRANT WORKERS' ACCOMMODATIONS - IOM Publications, accessed January 12, 2026, https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/MWG-Tool-5-Accomodation-checklist_0.pdf

25. Pregnant mothers' occupational factors linked to pregnancy complications - Ginekologia i Poloznictwo, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ginekologiaipoloznictwo.com/articles/pregnant-mothers-occupational-factors-linked-to-pregnancy-complications.pdf

26. Risk Factors for Working Pregnant Women and Potential ... - SSPH+, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ssph-journal.org/journals/international-journal-of-public-health/articles/10.3389/ijph.2023.1605655/full

27. Risk of infection and adverse outcomes among pregnant working women in selected occupational groups: A study in the Danish National Birth Cohort - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2994842/

28. Exposure to occupational hazards for pregnancy and sick leave in pregnant workers: a cross-sectional study - Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, accessed January 12, 2026, https://aoemj.org/journal/view.php?doi=10.1186/s40557-017-0170-3

29. TRIPLE DISCRIMINATION: WOMAN, PREGNANT, AND MIGRANT, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.fairlabor.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/triple_discrimination_woman_pregnant_and_migrant_march_2018.pdf

30. List of occupational diseases (revised 2010). Identification and recognition of occupational diseases: Criteria for incorporating diseases in the ILO list of occupational diseases, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/publications/list-occupational-diseases-revised-2010-identification-and-recognition

31. What to Expect from Your Employer When You're Expecting | U.S. Department of Labor, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/maternal-health

32. Know Your Rights: Pregnant Workers Fairness Act - National Women's Law Center, accessed January 12, 2026, https://nwlc.org/resource/know-your-rights-pregnant-workers-fairness-act/

33. What You Should Know About the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act - EEOC, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.eeoc.gov/wysk/what-you-should-know-about-pregnant-workers-fairness-act

34. Providing Accommodations to Pregnant Employees - Jackson Lewis, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.jacksonlewis.com/insights/providing-accommodations-pregnant-employees

35. Guide to Safety and Health for Teen Workers - MOSH - Maryland Department of Labor, accessed January 12, 2026, https://labor.maryland.gov/labor/mosh/teenworkersguide.shtml

36. ILO Conventions on child labour - International Labour Organization, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/international-programme-elimination-child-labour-ipec/what-child-labour/ilo-conventions-child-labour

37. AN INTRODUCTION TO LEGALLY PROHIBITING HAZARDOUS WORK FOR CHILDREN - International Labour Organization, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/2024-04/C182_at_a_glance_EN.pdf

38. Keeping young workers safe: 10 tips for supervisors - Texas Department of Insurance, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.tdi.texas.gov/tips/safety/young-workers.html

39. ILO/C/182: Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention - Welcome to the United Nations, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/ILO_C_182.pdf

40. Teen Safety:Tips for Supervisors - Oklahoma.gov, accessed January 12, 2026, https://oklahoma.gov/content/dam/ok/en/labor/documents/safety-and-health/workplace-rights/child-labor/2021_0304_WPR_CL_TeenSafetySupervisorsOSHA.pdf

41. employer tips - Mass.gov, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.mass.gov/doc/employer-tips-for-keeping-young-workers-safe-on-the-job/download

42. Recommandation R162 - Recommandation (no 162) sur les ..., accessed January 12, 2026, https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/nrmlx_fr/f?p=1000:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID,P12100_LANG_CODE:312500,en:NO

43. R162 Older Workers Recommendation, 1980 - Global Action on Aging, accessed January 12, 2026, https://globalag.igc.org/elderrights/world/r162.htm

44. PROTECTING OLDER WORKERS' HEALTH IN LEGAL TERMS COMPARATIVELY EUROPEAN ACQUIS IN THE LIGHT OF ILO R162, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.geriatri.dergisi.org/uploads/pdf/pdf_TJG_1205.pdf

45. ILO List of Occupational Diseases (revised 2010) - International Labour Organization, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/publications/ilo-list-occupational-diseases-revised-2010

46. Health and Safety Needs of Older Workers (2004) - National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, accessed January 12, 2026, https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/10884/chapter/3

47. Regional Review of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration Member States of the United Nations Economic Comm, accessed January 12, 2026, https://migrationnetwork.un.org/system/files/docs/UNECE%20-%20GCM%20Regional%20Review%20Summary.pdf