A Comprehensive Literature Review of Acute Post hemorrhagic Anemia

Dr. Turdaliev S.O.

Dipanshu Chakole

Satish Thaodem

(Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Kyrgyzstan

Students, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Kyrgyzstan)

Abstract

Acute Post hemorrhagic Anemia (APHA) is a critical hematological condition defined by a rapid and significant reduction in red blood cell mass and hemoglobin concentration following acute, high-volume blood loss. This condition precipitates a state of hypovolemic shock, leading to impaired oxygen delivery to tissues, cellular hypoxia, and multi-organ dysfunction.1 The pathophysiology is complex, initiated by a cascade of neuroendocrine and cardiovascular compensatory mechanisms aimed at preserving perfusion to vital organs. However, with ongoing hemorrhage, these mechanisms fail, culminating in the "lethal triad" of metabolic acidosis, hypothermia, and coagulopathy—a self-perpetuating cycle that drives mortality.3 Diagnosis relies on an integrated approach, combining astute clinical assessment of shock, serial laboratory investigations, and targeted imaging or endoscopic procedures to identify the source of bleeding.5 Management has evolved significantly from aggressive crystalloid resuscitation to the modern paradigm of damage control resuscitation. This strategy emphasizes permissive hypotension, early and balanced transfusion of blood products to correct coagulopathy, and the use of minimally invasive surgical and interventional radiology techniques for definitive hemostasis.3 This review synthesizes the current understanding of APHA, underscoring the necessity of a rapid, protocol-driven, and multidisciplinary approach to mitigate its high morbidity and mortality.

Introduction

Anemia is a global health issue, broadly defined as a reduction in the number of circulating red blood cells (RBCs) or a deficiency in hemoglobin concentration, resulting in an oxygen-carrying capacity that is insufficient to meet the body's physiological demands.10 Affecting roughly one-third of the world's population, it is a significant contributor to morbidity, mortality, and impaired quality of life across all age groups.10 While many forms of anemia develop chronically, allowing for physiological adaptation, Acute Post hemorrhagic Anemia (APHA), identified by the ICD-10 code D62, represents a distinct and life-threatening clinical entity.3

APHA is characterized by an abrupt and substantial loss of intravascular volume due to acute hemorrhage.1 This rapid depletion of whole blood distinguishes it from chronic anemias; the body has no time to adapt, and the clinical presentation is dominated not by the signs of anemia itself, but by the profound hemodynamic instability of hypovolemic shock.13 The hemorrhage can be from an external source, such as in major trauma, or an internal one, such as a ruptured aortic aneurysm, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, or an ectopic pregnancy.6 Understanding the intricate pathophysiological cascade that follows acute blood loss is fundamental to appreciating the rationale behind modern diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Pathophysiology of Acute Blood Loss

The core physiological insult in APHA is the rapid depletion of circulating blood volume, which initiates a complex, multi-system response. This response is initially adaptive, designed to maintain perfusion to the brain and heart at the expense of other tissues, but it can quickly become maladaptive, leading to irreversible shock and death.2

Immediate Compensatory Mechanisms: The Neuroendocrine and Cardiovascular Response

The body's first line of defense against hemorrhage is a powerful neuroendocrine reflex. A decrease in blood volume leads to reduced cardiac filling, which in turn lowers cardiac output and arterial pressure. This pressure drop is immediately sensed by high-pressure baroreceptors in the carotid sinus and aortic arch, as well as low-pressure stretch receptors in the atria and ventricles.14 The integrated signal triggers a profound activation of the sympathetic nervous system and inhibits parasympathetic tone.14 This results in a massive release of catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) from the adrenal medulla, which reinforces the effects of direct sympathetic innervation.14

The cardiovascular effects are swift and potent, aimed at preserving mean arterial pressure. Heart rate and myocardial contractility increase to maximize cardiac output from the diminished venous return, while intense arteriolar vasoconstriction increases systemic vascular resistance.3 This vasoconstriction is not uniform; it preferentially shunts blood away from less critical vascular beds—such as the skin (causing pallor and coolness), skeletal muscles, and the splanchnic circulation (gut and kidneys)—to preserve flow to the heart and brain.14 This initial response is remarkably effective, often maintaining a near-normal blood pressure even with up to 30% loss of blood volume.16 However, this compensatory phase can be biphasic; after a critical volume loss (around one-third of total blood volume), a paradoxical "switching off" of sympathetic drive can occur, triggered by cardiac signals, leading to an abrupt and dangerous fall in blood pressure and peripheral resistance.18

Delayed Compensatory Mechanisms: Renal, Hormonal, and Interstitial Fluid Shifts

As the immediate neuroendocrine response is underway, slower but equally vital mechanisms are activated to restore intravascular volume. Reduced blood flow to the kidneys stimulates the juxtaglomerular apparatus to release renin, activating the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS).3 Angiotensin II, a powerful vasoconstrictor, further increases systemic vascular resistance. Aldosterone acts on the renal tubules to promote the reabsorption of sodium and water, a crucial mechanism for long-term volume conservation.15 Concurrently, hypotension and sympathetic stimulation trigger the release of vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone) from the pituitary gland, which enhances water retention by the kidneys and contributes to vasoconstriction.15

Perhaps the most critical delayed mechanism for volume restoration is the transcapillary refill. The combination of arterial hypotension and precapillary vasoconstriction leads to a significant drop in hydrostatic pressure within the capillaries. This alters the balance of Starling forces, causing a net movement of protein-free, cell-free fluid from the interstitial space back into the vascular compartment.3 This process can shift up to one liter of fluid per hour, effectively replenishing plasma volume.15 This fluid shift, however, creates a significant clinical pitfall. Because whole blood is lost initially, the concentration of hemoglobin in the remaining blood is unchanged.6 It is only after this process of hemodilution occurs over several hours that the hemoglobin and hematocrit values begin to fall on laboratory testing.13 Consequently, an early complete blood count (CBC) can be deceptively normal, providing false reassurance in a patient who has sustained a life-threatening hemorrhage. Clinical signs of shock, such as tachycardia and cool extremities, are far more sensitive early indicators of significant blood loss than the initial hemoglobin level.

Decompensation and the "Lethal Triad": The Vicious Cycle of Acidosis, Hypothermia, and Coagulopathy

When blood loss continues and compensatory mechanisms are overwhelmed, the patient enters a state of decompensated shock. Critically impaired tissue perfusion forces cells to switch from efficient aerobic metabolism to inefficient anaerobic metabolism. The primary byproduct of this shift is lactic acid, which accumulates in the bloodstream, overwhelms the body's buffering capacity, and results in a profound metabolic acidosis.3

Simultaneously, hypothermia (a core body temperature below 35°C or 95°F) develops. This is caused by a combination of factors: decreased metabolic heat production due to shock, increased heat loss from environmental exposure (particularly in trauma patients), and the administration of cold intravenous fluids and blood products.3

The combination of acidosis and hypothermia has a devastating effect on hemostasis, leading to coagulopathy. The enzymatic reactions of the coagulation cascade are exquisitely sensitive to temperature and pH, and their function is severely impaired in cold, acidic environments.3 Platelet aggregation and function are also inhibited.21 This acquired coagulopathy is compounded by the loss of clotting factors and platelets in the shed blood and their dilution by crystalloid resuscitation fluids.3

These three conditions—acidosis, hypothermia, and coagulopathy—form a self-perpetuating "vicious cycle" often termed the "lethal triad of trauma".3 Coagulopathy leads to more bleeding, which worsens shock, thereby deepening the acidosis and hypothermia, which in turn further impairs coagulation.4 This recognition has fundamentally shifted the focus of modern resuscitation. Interventions such as actively warming the patient with forced-air blankets and warmed fluids are no longer considered mere "supportive care" but are understood as primary hemostatic therapies aimed at restoring the enzymatic function of the coagulation cascade and breaking this lethal cycle.22

Classification

To effectively manage APHA, clinicians require a framework to rapidly assess the severity of hemorrhage and guide resuscitation. While APHA can be categorized within standard hematological systems, the most critical classification in the acute setting is based on the physiological response to blood loss.

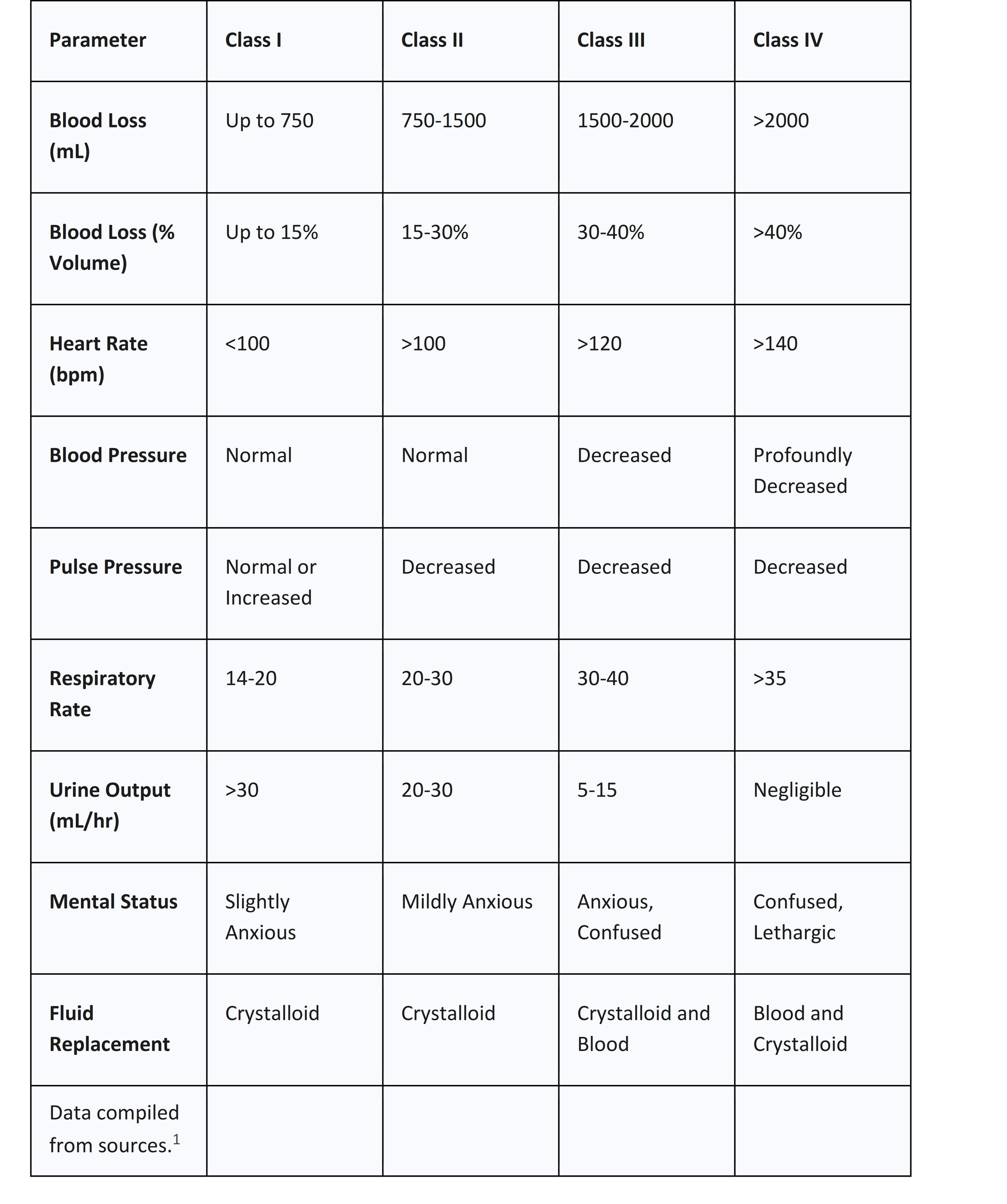

The Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) Classification of Hemorrhage

The most widely recognized and utilized system for grading acute hemorrhage is the classification developed by the American College of Surgeons' Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) program.3 This system categorizes hemorrhage into four classes based on the estimated percentage of blood volume lost and the corresponding physiological derangements observed in a typical 70 kg adult. Its primary utility is providing a common language for clinicians to rapidly estimate the severity of blood loss, anticipate the patient's trajectory, and determine the urgency and type of intervention required.3

The classes represent points along a continuum of physiological decompensation. A patient with ongoing hemorrhage can progress rapidly from one class to the next, making serial reassessment a cornerstone of clinical management. The response, or lack thereof, to initial interventions provides crucial diagnostic and prognostic information. For instance, a patient in Class III who transiently improves with a fluid bolus only to become hypotensive again is demonstrating ongoing, significant hemorrhage that requires definitive control.8 Thus, the ATLS classification is best utilized as a dynamic tool for monitoring the interplay between blood loss, physiological compensation, and the efficacy of resuscitation, rather than as a static label assigned at a single point in time.

Table 1: ATLS Classification of Hemorrhagic Shock

The transition from Class II to Class III is a critical inflection point, marking the failure of the body's compensatory mechanisms and representing the shift from compensated to decompensated shock. This is the stage where hypotension becomes evident and the need for blood product transfusion becomes unequivocal.3

Morphological and Kinetic Approaches to Anemia

Beyond the immediate classification of shock, the anemia itself can be categorized using standard hematological frameworks, which becomes more relevant once the patient is stabilized.

● Morphological Approach: This approach classifies anemia based on RBC size, as indicated by the Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV). Because acute hemorrhage involves the loss of whole blood, APHA is initially a normocytic, normochromic anemia (MCV 80-100 fL).1 In the days following the hemorrhage, as the bone marrow mounts a robust response by releasing large, immature RBCs (reticulocytes), the MCV may temporarily increase. If the blood loss is substantial or recurrent and depletes the body's iron stores, the condition can evolve into a microcytic, hypochromic anemia characteristic of iron deficiency.13

● Kinetic Approach: This framework classifies anemia based on its underlying mechanism. APHA falls squarely into the category of anemia due to blood loss.26 This distinguishes it from anemias caused by decreased RBC production (e.g., aplastic anemia, nutritional deficiencies) or increased RBC destruction (hemolytic anemias). It is important to recognize, however, that these categories are not mutually exclusive, and a patient may have a multifactorial anemia, such as APHA superimposed on a chronic anemia of inflammation.29

Causes and Risk Factors

The etiologies of APHA are diverse, ranging from traumatic injuries to underlying medical conditions that predispose an individual to severe bleeding. Understanding these risk factors is crucial for both prevention and rapid diagnosis. The development of APHA is often not the result of a single factor but rather the culmination of a pre-existing vulnerability combined with an acute insult. The clinical outcome in such cases is often worse than what would be predicted by either factor alone, reflecting a synergistic compromise of the patient's physiological reserves. For example, an elderly patient with baseline anemia from chronic kidney disease who is taking aspirin for cardiovascular prevention has multiple vulnerabilities: reduced tolerance to blood loss, impaired platelet function, and potentially a blunted cardiovascular response to shock. If this patient sustains a traumatic hip fracture, their risk of rapid decompensation is profoundly elevated compared to a healthy young individual with the same injury.5

Genetic Factors

Certain inherited conditions significantly increase the risk of APHA by impairing the body's intrinsic ability to achieve hemostasis.

● Inherited Coagulopathies: Disorders such as hemophilia (deficiency of Factor VIII or IX) and von Willebrand disease (deficiency or dysfunction of von Willebrand factor) disrupt the coagulation cascade, leading to prolonged and excessive bleeding from injuries that might otherwise be minor.5

● Inherited RBC Disorders: While primarily causing hemolytic anemia, conditions affecting RBC structure and function can contribute to a patient's overall hematological fragility. Hereditary spherocytosis and elliptocytosis result in abnormally shaped, fragile RBCs that are more easily destroyed, potentially worsening the degree of anemia from any cause.1 Similarly, patients with sickle cell disease or thalassemia have an underlying anemia and may experience complications that increase bleeding risk.11

Maternal Factors: Postpartum Hemorrhage

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is a specific and major cause of APHA in the obstetric population and remains a leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide.31 PPH is most commonly defined as a blood loss of more than 500 mL after vaginal delivery or 1,000 mL after a cesarean section. It can be classified as primary (occurring within the first 24 hours of delivery) or secondary (occurring from 24 hours to 12 weeks postpartum).31 The causes are systematically remembered by the mnemonic of the "4 T's".31

● Tone (Uterine Atony): This is the most frequent cause, accounting for 70-80% of PPH cases.31 It involves the failure of the uterine myometrium to contract sufficiently after delivery to compress the spiral arteries that supplied the placenta. Risk factors include conditions that overdistend the uterus (e.g., multiple gestation, fetal macrosomia, polyhydramnios), prolonged or very rapid labor, infection (chorioamnionitis), and the use of uterine-relaxing medications like magnesium sulfate.35

● Trauma: Lacerations to the genital tract, including the cervix, vagina, perineum, or uterus itself (uterine rupture), can cause significant bleeding. Risk factors include operative vaginal delivery (forceps or vacuum), cesarean delivery, and precipitous birth.31

● Tissue: The retention of placental fragments or blood clots within the uterus can impede effective contraction and lead to ongoing bleeding. Abnormal placental implantation, such as placenta accreta (where the placenta invades the uterine wall too deeply), is a particularly high-risk condition.35

● Thrombin: Coagulation abnormalities, whether pre-existing (like von Willebrand disease) or acquired during pregnancy (such as in HELLP syndrome, severe preeclampsia, or amniotic fluid embolism), can prevent adequate clot formation at the placental site.31

Environmental and Other Acquired Factors

This broad category encompasses the most common causes of APHA seen in the general population.

● Trauma and Surgery: Direct physical injury is a primary cause of massive blood loss. Penetrating trauma (e.g., gunshot or stab wounds) and blunt trauma (e.g., motor vehicle collisions, falls) can rupture major blood vessels or solid organs.12 Major surgical procedures, particularly cardiovascular, orthopedic, and abdominal surgeries, carry an inherent risk of significant hemorrhage.5

● Gastrointestinal (GI) Bleeding: This is a major cause of APHA. Upper GI sources include bleeding from peptic ulcers, esophageal or gastric varices (often in the context of liver disease), and severe gastritis.28 Lower GI bleeding can arise from diverticulosis, angiodysplasia, or malignancy.

● Medications: The use of certain medications is a prominent risk factor.

○ Antithrombotic Agents: Anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin, direct oral anticoagulants) and antiplatelet drugs (e.g., aspirin, clopidogrel) are designed to inhibit clotting and are therefore a major risk for exacerbating or causing hemorrhage.5

○ NSAIDs and Corticosteroids: Chronic use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroids can damage the gastric mucosa, leading to gastritis and peptic ulcer formation, which can then bleed.28

● Other Medical Conditions:

○ Aneurysm Rupture: A localized, weakened area in a blood vessel wall (aneurysm), such as in the aorta or a cerebral artery, can rupture, causing catastrophic and often fatal internal bleeding.39

○ Ruptured Ectopic Pregnancy: This occurs when a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus, most commonly in a fallopian tube. As the pregnancy grows, it can rupture the tube, leading to severe intra-abdominal hemorrhage—a surgical emergency.13

○ Pre-existing Anemia: Patients with underlying anemia from chronic conditions (e.g., chronic kidney disease, malignancy) or nutritional deficiencies have diminished physiological reserves and tolerate acute blood loss poorly.11

Diagnostic Techniques

The diagnosis of APHA requires a rapid, integrated approach that combines clinical assessment with targeted laboratory and imaging studies. In the setting of severe hemorrhage, diagnostic and therapeutic interventions often occur in parallel. While the clinical team initiates resuscitation to stabilize the patient's circulation, a simultaneous investigation must be launched to identify the source of bleeding, as definitive treatment is impossible without source control. This parallel processing is a core tenet of managing the critically bleeding patient; one cannot wait for a complete diagnostic picture before starting life-saving treatment, and treatment will ultimately fail if the underlying cause is not found and addressed.1

Clinical Presentation and Physical Examination

The diagnosis of APHA should be suspected in any patient presenting with signs of shock, particularly when there is a known history of trauma, recent surgery, or conditions predisposing to bleeding.6

● Symptoms: The patient's symptoms are a direct consequence of hypovolemia and inadequate tissue oxygenation. Common complaints include profound weakness, fatigue, dizziness or syncope (especially with changes in posture), shortness of breath, palpitations, confusion, and chest pain.1

● Physical Signs: The physical examination provides critical clues to the severity of hemorrhage, reflecting the body's compensatory responses. Key signs are those of hemorrhagic shock as outlined in the ATLS classification:

○ Tachycardia: An early and sensitive sign of volume loss.1

○ Hypotension: A later and more ominous sign, indicating decompensation.3

○ Tachypnea: Increased respiratory rate to compensate for metabolic acidosis.3

○ Cutaneous Signs: Pale, cool, and clammy skin due to peripheral vasoconstriction.5

○ Other Signs: A narrowed pulse pressure (the difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure) is an early indicator of decreased stroke volume. Oliguria (decreased urine output) reflects reduced renal perfusion.1

● Localizing the Bleed: A focused physical examination can help identify the source of bleeding. Obvious external wounds are assessed in trauma. In cases of internal hemorrhage, specific signs are sought, such as abdominal tenderness or distention, or ecchymosis like the Cullen sign (periumbilical) or Grey Turner sign (flank), which suggest retroperitoneal bleeding.6

Laboratory Investigations

Laboratory tests are essential to quantify the extent of anemia, assess coagulation status, and prepare for transfusion.

● Complete Blood Count (CBC): This is the fundamental test, providing values for hemoglobin, hematocrit, and platelet count.5 As previously discussed, initial hemoglobin and hematocrit levels can be misleadingly normal due to the time lag for hemodilution. Therefore, serial CBCs are crucial to monitor the trend and response to resuscitation.6 The platelet count is vital, as thrombocytopenia can cause or exacerbate bleeding.

● Coagulation Studies: A standard coagulation panel, including Prothrombin Time (PT/INR) and activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT), is mandatory to detect pre-existing or acquired coagulopathy.5 A fibrinogen level should also be measured, as it is one of the first clotting factors to be depleted in massive hemorrhage.

● Blood Type and Crossmatch: This is an emergent priority to ensure compatible blood products are available for transfusion.43

● Other Tests: A reticulocyte count, typically elevated a few days after the event, confirms an appropriate bone marrow response.13 Arterial or venous blood gas analysis provides immediate information on the degree of metabolic acidosis (via base deficit or lactate) and oxygenation status.44

Imaging and Endoscopy

Once the patient is sufficiently stabilized, or if the source of bleeding is not apparent, imaging and endoscopic procedures are employed to locate the hemorrhage.

● Endoscopy: For suspected GI bleeding, upper endoscopy or colonoscopy is the diagnostic modality of choice. It offers direct visualization of the mucosal lining, allowing for precise localization of the bleeding source (e.g., ulcer, varix, tumor) and often provides the opportunity for immediate therapeutic intervention.13

● Computed Tomography (CT) Angiography: This is a rapid, non-invasive imaging technique that is invaluable in the evaluation of the trauma patient or in cases of suspected bleeding of an unknown source. By administering intravenous contrast, the scan can detect active extravasation of contrast from a damaged blood vessel, pinpointing the location of the bleed with high accuracy. This information is critical for planning either surgical or interventional radiology procedures.3

● Ultrasound: The Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST) exam is a rapid, bedside ultrasound protocol used in trauma centers to detect the presence of free fluid (hemoperitoneum or hemothorax) in the abdominal and thoracic cavities, respectively.6 While it does not identify the specific source of bleeding, a positive FAST scan in an unstable patient is often an indication for immediate exploratory laparotomy.

Management Strategies

The management of APHA is a time-sensitive, multidisciplinary endeavor focused on three simultaneous goals: restoring circulating volume to maintain tissue perfusion, achieving definitive control of the bleeding source, and preventing or reversing the lethal triad of acidosis, hypothermia, and coagulopathy. The complexity of this process has led to the development of "massive hemorrhage protocols" in many institutions, which facilitate the rapid, coordinated response of emergency physicians, surgeons, anesthesiologists, interventional radiologists, hematologists, and blood bank personnel. This "hemorrhage team" approach ensures that all necessary expertise and resources are mobilized concurrently, reflecting a shift away from sequential, siloed care toward a more integrated and effective model.3

Medical Management

Medical management forms the foundation of resuscitation and physiological support.

Initial Resuscitation: The ABCs

The immediate priority in any critically ill patient is to follow the principles of advanced life support: ensuring a patent Airway, optimizing Breathing and oxygenation, and addressing the failure of Circulation.1 Securing two large-bore (e.g., 14 or 16 gauge) peripheral intravenous lines is a critical first step to allow for rapid administration of fluids and blood products.1

Fluid and Volume Replacement: A Paradigm Shift

The approach to volume replacement has undergone a significant evolution. The historical practice of administering large volumes of isotonic crystalloid solutions (e.g., normal saline or lactated Ringer's) is now recognized to be harmful in the setting of uncontrolled hemorrhage.8 This strategy exacerbates the lethal triad by diluting clotting factors and platelets (worsening coagulopathy), contributing to hypothermia (if fluids are not warmed), and potentially worsening acidosis.3

The modern strategy is known as Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR). Key principles of DCR include 3:

● Permissive Hypotension: In patients without traumatic brain injury, the goal is not to restore normal blood pressure immediately. Instead, a lower systolic blood pressure target (e.g., 80-90 mmHg) is accepted until the bleeding is surgically controlled. This is thought to prevent the dislodgement of newly formed clots ("popping the clot") that can occur with higher hydrostatic pressures.8

● Hemostatic Resuscitation: This involves minimizing the use of crystalloids and prioritizing the early administration of blood products in a balanced ratio of packed red blood cells (PRBCs), fresh frozen plasma (FFP), and platelets, often approaching a 1:1:1 ratio. This strategy aims to replace whole blood loss in kind, thereby treating the underlying coagulopathy from the outset.3

Blood Transfusion Principles

The decision to transfuse blood is a clinical one, guided by the patient's hemodynamic status rather than a single hemoglobin value. In the context of active, life-threatening hemorrhage (e.g., ATLS Class III or IV), transfusion is initiated emergently as part of DCR.3

For critically ill patients who are hemodynamically stable and not actively bleeding, a restrictive transfusion strategy is the standard of care. This approach, supported by numerous clinical trials, recommends withholding transfusion until the hemoglobin level falls below a threshold of 7 g/dL.43 This strategy has been shown to be non-inferior to more liberal approaches and is associated with a lower risk of transfusion-related complications. Unless the patient is actively bleeding, it is recommended to transfuse one unit of PRBCs at a time, followed by a clinical and laboratory reassessment.43

Surgical and Interventional Radiology Management

Medical resuscitation stabilizes the patient but does not stop the hemorrhage. Definitive hemostasis requires a procedural intervention.

● Damage Control Surgery: For severely injured trauma patients in deep shock, a lengthy, definitive operation is poorly tolerated. Damage control surgery is an abbreviated procedure focused exclusively on the rapid control of hemorrhage (e.g., packing the liver, ligating vessels) and contamination. The abdomen is temporarily closed, and the patient is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for physiological restoration—warming, correction of acidosis, and reversal of coagulopathy. Once stabilized, the patient returns to the operating room for a planned second-look surgery and definitive repairs.23

● Interventional Radiology: Transcatheter Arterial Embolization (TAE) has become a first-line therapy for controlling many types of hemorrhage. It is a minimally invasive procedure where an interventional radiologist navigates a catheter through the arterial system under imaging guidance to the site of bleeding. The bleeding vessel is then occluded (embolized).51 This technique is highly effective for bleeding from solid organ injuries (spleen, liver, kidney), pelvic fractures, and GI bleeding that has failed endoscopic therapy.9 A variety of embolic agents can be used:

○ Coils: Tiny platinum coils are deployed into the vessel to induce thrombosis. They are a permanent embolic agent.9

○ Gelfoam (Gelatin Sponge): This is a temporary agent that is cut into small pieces and injected as a slurry. It causes occlusion but is resorbed by the body over several weeks, allowing for potential recanalization of the vessel.9

○ Particles and Liquid Embolics: Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles or liquid glues can also be used for permanent occlusion, particularly in the setting of bleeding tumors or vascular malformations.45

Role of Interventional Cardiology

While interventional radiologists manage hemorrhage throughout most of the body, interventional cardiologists are central to managing iatrogenic bleeding complications that arise during cardiac catheterization procedures.53 Coronary artery perforation during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is a rare but potentially fatal event that can cause rapid bleeding into the pericardial space, leading to cardiac tamponade.53 Immediate management by the interventional cardiologist includes prolonged inflation of a balloon at the site of the perforation to tamponade the bleed internally. If this is not successful, a specialized covered stent can be deployed to mechanically seal the hole in the vessel wall.53 In refractory cases, emergent consultation with a cardiac surgeon or interventional radiologist for embolization may be necessary.53

Lifelong Follow-Up and Secondary Prevention

Management extends beyond the acute hospitalization. The goals of long-term follow-up are to ensure full hematological recovery, prevent recurrence of bleeding, and manage any complications arising from the acute event or its treatment.

● Hematological Recovery: After the bleeding is controlled, patients require regular monitoring of their hemoglobin levels.38 Replenishing the body's iron stores is critical for the bone marrow to effectively produce new RBCs. This is typically achieved with oral or intravenous iron supplementation, which may be needed for three to six months.5

● Prevention of Recurrence: The cornerstone of secondary prevention is addressing the underlying cause of the hemorrhage. This is highly individualized and may involve:

○ For GI bleeding: Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and use of proton pump inhibitors for peptic ulcer disease, or endoscopic banding for esophageal varices.41

○ For patients on antithrombotic therapy: A careful reassessment of the risks and benefits of treatment, potentially adjusting the regimen or adding gastroprotective agents.55

○ For trauma: Patient education on safety measures to prevent future injuries.39

○ For PPH: Counseling on risks in future pregnancies.

Regular follow-up with the appropriate specialist (e.g., gastroenterologist, hematologist, cardiologist) is essential to monitor and manage these underlying conditions.38

● Monitoring for Complications: Patients who required massive transfusion are at risk for late complications and require vigilant monitoring in the ICU. These include pulmonary complications like Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury (TRALI) and Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload (TACO), as well as ongoing metabolic disturbances such as hypocalcemia (from citrate in blood products), hyperkalemia (from lysis of stored RBCs), and persistent coagulopathy.47 This necessitates frequent laboratory monitoring of CBC, coagulation profiles, electrolytes, and arterial blood gases, along with continuous hemodynamic and temperature monitoring.58

Methodology

This literature review was conducted to provide a comprehensive and synthesized overview of the current state of knowledge regarding Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia. The methodology was designed to be systematic and transparent to ensure the credibility and robustness of the findings.

Literature Search Strategy

A comprehensive search of the extant literature was performed using major electronic scholarly databases, primarily PubMed/MEDLINE and Google Scholar.60 The search strategy employed a combination of keywords and MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms. Core search terms included: "acute posthemorrhagic anemia," "hemorrhagic shock," "pathophysiology," "damage control resuscitation," "massive transfusion," "lethal triad," "postpartum hemorrhage," "transcatheter arterial embolization," and "clinical prediction models." The search was expanded by reviewing the reference lists of key articles to identify additional relevant publications.

Study Selection and Inclusion Criteria

The selection of literature followed a two-stage screening process to ensure relevance and quality.60 In the first stage, titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles were screened. Studies were included for full-text review if they directly addressed the pathophysiology, classification, etiology, diagnosis, or management of APHA or hemorrhagic shock. In the second stage, the full-text articles were assessed against predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were: (1) peer-reviewed publications, including original research articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and authoritative clinical guidelines; (2) focus on human subjects; and (3) publication in the English language. Articles were excluded if they were single case reports without a broader review component, non-scholarly publications (e.g., news articles), or studies with significant methodological limitations that would compromise the validity of their findings.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

For each included article, relevant data were systematically extracted and organized according to the major themes of this review.60 Information was charted covering definitions, pathophysiological concepts, risk factors, diagnostic criteria and techniques, management protocols and interventions, and patient outcomes. The extracted data were then collated and synthesized into a coherent narrative. The objective of this synthesis was to aggregate findings from disparate sources, identify consistent patterns and evolving paradigms, and construct a comprehensive, evidence-based overview of the topic.62

Ethical Considerations

As this study is a literature review based entirely on previously published and publicly available data, it did not involve any new research on human or animal subjects. Consequently, institutional review board (IRB) approval was not required. All sources utilized in this review are appropriately cited to acknowledge the work of the original authors and maintain academic integrity.

Modeling and Analysis

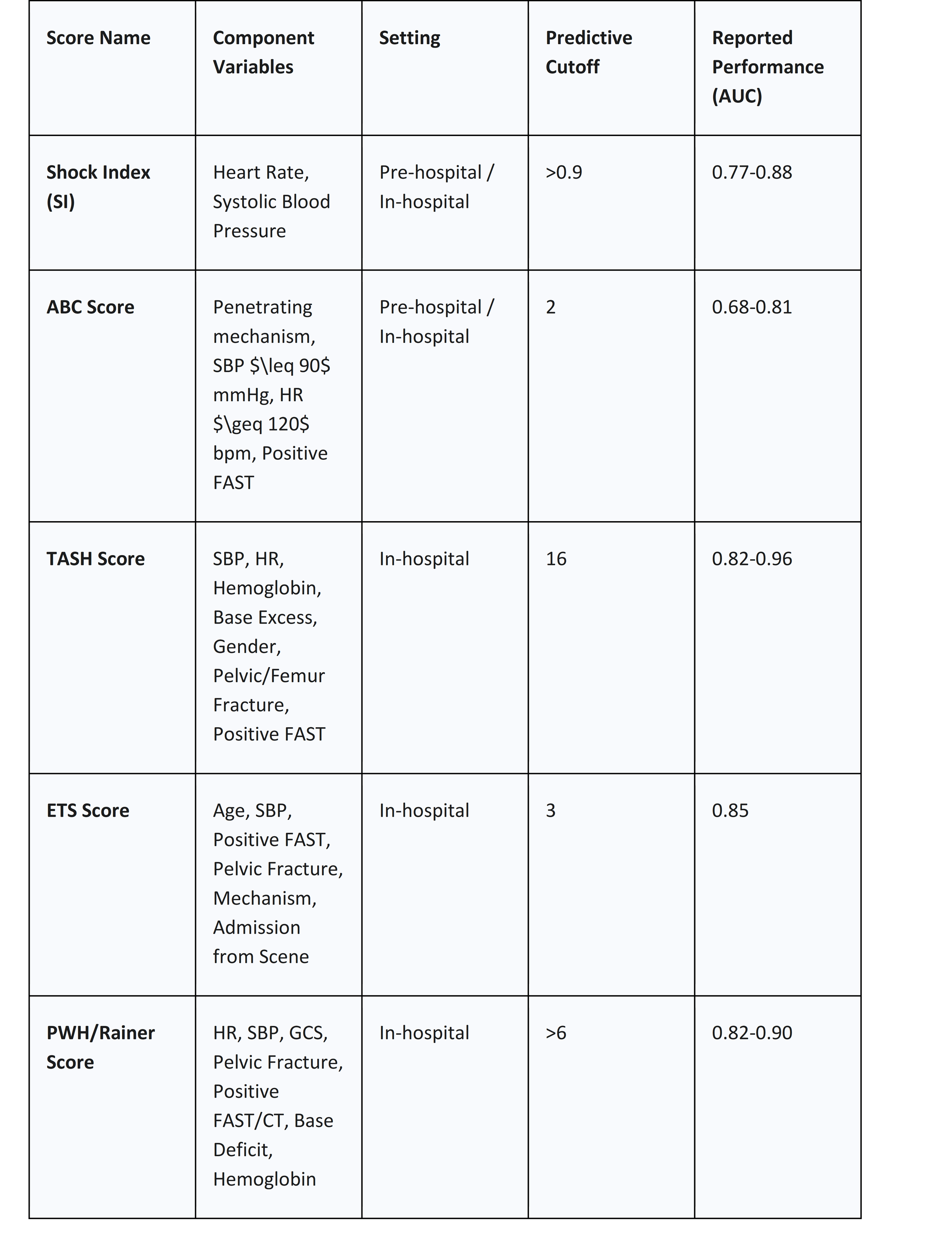

In the high-stress, time-critical environment of an acute hemorrhage, clinical decision-making can be challenging. To augment clinical judgment and promote a standardized, rapid response, several clinical prediction models and scoring systems have been developed. Their primary purpose is to identify, as early as possible, those patients who are at high risk of requiring a massive transfusion (MT), typically defined as the transfusion of 10 or more units of packed red blood cells within 24 hours.63 Early and accurate prediction allows for the preemptive activation of a hospital's Massive Hemorrhage Protocol (MHP), which mobilizes critical resources from the blood bank and alerts the multidisciplinary hemorrhage team, thereby reducing delays in care.56

Analysis of Key Scoring Systems

The available scoring systems vary in their complexity and the setting in which they are designed to be used. A notable trend is the inherent trade-off between the simplicity required for rapid pre-hospital or initial emergency department assessment and the enhanced accuracy afforded by incorporating laboratory data, which is only available later in the patient's course. This means there is no single "best" score; rather, the choice of tool is context-dependent. Simple scores like the Shock Index or ABC score are invaluable for the initial triage and MHP activation decision, providing a "good enough" prediction with minimal delay.63 More complex scores like TASH, which require laboratory inputs, are better suited for the second phase of resuscitation, helping to confirm the need for ongoing massive transfusion or to guide de-escalation of the MHP once initial results are available.63

● Shock Index (SI): Calculated simply as Heart Rate divided by Systolic Blood Pressure (HR/SBP). It is the most basic score and can be easily calculated in any setting, including pre-hospital. An SI greater than 0.9 is considered predictive of the need for MT and is associated with increased mortality.63

● Assessment of Blood Consumption (ABC) Score: A simple, four-component bedside score. One point is given for each of the following: penetrating mechanism of injury, arrival systolic blood pressure 90 mmHg, arrival heart rate 120 bpm, and a positive FAST exam. A score of 2 or more has good specificity for predicting the need for MT and is widely used to trigger MHP activation.63

● Trauma Associated Severe Hemorrhage (TASH) Score: A more complex, weighted logistic regression model that incorporates seven clinical and laboratory variables: SBP, heart rate, gender, hemoglobin, base excess, presence of intra-abdominal fluid on ultrasound, and clinically unstable pelvic or femur fractures. It is highly accurate but requires laboratory results, limiting its use to the in-hospital setting.63

● Emergency Transfusion Score (ETS): This score incorporates six variables: age, SBP, free fluid on FAST, unstable pelvic fracture, mechanism of injury, and admission from the scene of the accident. It has a very high negative predictive value, meaning a low score can reliably rule out the need for MT.64

Table 2: Comparison of Clinical Prediction Scores for Massive Hemorrhage

Results and Discussion

This comprehensive review of Acute Post hemorrhagic Anemia reveals it to be far more than a simple deficit of red blood cells. It is a complex, systemic disease process defined by the dynamic interplay of hemorrhagic shock, metabolic collapse, and coagulopathy. Successful management is predicated on a deep understanding of this pathophysiology and requires a rapid, integrated, and multidisciplinary response that addresses both the physiological derangements and the underlying source of bleeding.

Synthesis of Findings: A Multi-faceted Clinical Challenge

The evidence synthesized in this review underscores that the immediate threat in APHA is hypovolemic shock, not anemia itself. The body's initial compensatory responses, while elegant, are finite and can be overwhelmed, leading to the precipitous decline into the lethal triad. This pathophysiological cascade forms the central organizing principle for modern management. The ATLS classification provides the clinical language to stage this decline, which in turn dictates the therapeutic strategy. For example, the recognition of Class III hemorrhage is the trigger to move beyond simple fluid administration to hemostatic resuscitation with blood products. Similarly, the underlying cause of the bleed dictates the diagnostic and therapeutic pathway—a patient with hematemesis is triaged toward emergent endoscopy, while a patient with a positive FAST scan after a car crash is triaged toward the operating room or interventional radiology suite. This highlights the need for rapid, parallel processing of diagnosis and treatment.

Evolving Paradigms in Hemorrhagic Shock Resuscitation

One of the most significant themes emerging from the recent literature is the radical paradigm shift in resuscitation strategy. The traditional approach, which focused on rapidly restoring normotension with large volumes of crystalloid fluid, has been largely abandoned due to compelling evidence of iatrogenic harm.3 This older model was found to worsen all three components of the lethal triad: it dilutes clotting factors, induces hypothermia, and can exacerbate acidosis.47

The modern paradigm of Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) is built on a more nuanced physiological understanding. By embracing permissive hypotension, clinicians avoid the risk of dislodging fragile clots while maintaining perfusion to vital organs.8 By prioritizing the early, balanced administration of PRBCs, plasma, and platelets, DCR treats the acute traumatic coagulopathy as a primary target of resuscitation, not an afterthought.3 Furthermore, the advent and increasing use of whole-blood viscoelastic hemostatic assays, such as thromboelastography (TEG) and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM), represent another major advance. These point-of-care tests provide a real-time, functional assessment of the entire clotting process, allowing for a more precise, goal-directed transfusion therapy that moves beyond the static and often delayed information provided by standard coagulation tests like the PT and aPTT.56

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite these advances, significant challenges remain. The pre-hospital management of severe hemorrhage is a critical area for improvement, as delays in reaching definitive care are a major determinant of outcome. The logistics of providing blood products in remote, rural, or military settings are substantial. The increasing prevalence of patients on novel oral anticoagulants, for which reversal agents may be unavailable or unfamiliar to clinicians, presents a growing challenge in managing both traumatic and spontaneous bleeding.53

Future research will likely focus on several key areas. The development of more accurate, non-invasive, and continuous monitors of tissue perfusion and shock state could allow for earlier recognition of decompensation. The application of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms to integrate vast amounts of physiological data may lead to more sophisticated and personalized predictive models for massive hemorrhage.67 Finally, the ongoing search for effective and safe artificial oxygen carriers ("blood substitutes") and novel systemic hemostatic agents continues, with the hope of providing new tools to manage the most exsanguinating patients.

Conclusion

Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia is a time-critical medical emergency in which patient survival is directly contingent on the speed and efficacy of the clinical response. Its management is a profound clinical challenge, demanding a sophisticated understanding of the pathophysiology of shock and a highly coordinated, multidisciplinary effort. The foundation of successful treatment rests on a dual strategy: aggressive, protocol-driven physiological resuscitation aimed at preventing and reversing the lethal triad of acidosis, hypothermia, and coagulopathy, which must be executed in parallel with a rapid and systematic investigation to identify and definitively control the source of hemorrhage.

The evolution from traditional fluid resuscitation to the modern principles of damage control—including permissive hypotension and early, balanced blood product transfusion—represents a major advance in the field, grounded in a better understanding of the iatrogenic harms of previous approaches. The integration of surgical, endoscopic, and minimally invasive interventional radiology techniques provides a powerful and flexible armamentarium for achieving hemostasis. As the population ages and the use of antithrombotic medications increases, the incidence and complexity of managing APHA will likely continue to grow. Therefore, continued research, refinement of clinical protocols, and emphasis on multidisciplinary team training are essential to further improve outcomes for patients with this life-threatening condition.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the Department of Hospital Therapy for their valuable guidance, support, and encouragement throughout the preparation of this article.

I am especially thankful to Dr. Turdaliev Sir, Head of the Department, for their expert advice and constructive feedback.

I also extend my appreciation to all the faculty members and hospital staff who provided insightful information and practical experience, which greatly enriched the content of this work.

References

1. Acute Anemia - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf - NIH, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537232/

2. Clinical review: Hemorrhagic shock - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1065003/

3. Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia: A Comprehensive Literature Review of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Contemporary Management - ijrpr, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://ijrpr.com/uploads/V6ISSUE10/IJRPR54024.pdf

4. The trauma triad of death: hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy - PubMed, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10347389/

5. Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia - What You Need to Know - Drugs.com, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.drugs.com/cg/acute-posthemorrhagic-anemia.html

6. Chapter 101: Anemia Due to Acute Blood Loss - AccessMedicine, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?legacysectionid=hpim21_ch101

7. Anemia - Diagnosis, Evaluation and Treatment - Radiologyinfo.org, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/anemia

8. An approach to transfusion and hemorrhage in trauma: current perspectives on restrictive transfusion strategies - PubMed Central, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2384284/

9. “Beyond saving lives”: Current perspectives of interventional radiology in trauma - PMC, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5415886/

10. Anemia epidemiology, pathophysiology, and etiology in low- and middle-income countries, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6697587/

11. Anemia - Symptoms and causes - Mayo Clinic, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anemia/symptoms-causes/syc-20351360

12. Acute posthemorrhagic anemia - Wikipedia, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acute_posthemorrhagic_anemia

13. Anemia Due to Acute Blood Loss | Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e | AccessMedicine, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2129§ionid=192017550

14. Pathophysiology of Acute Hemorrhagic Shock - Fluid Resuscitation - NCBI Bookshelf - NIH, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK224592/

15. Hemorrhagic Shock - CV Physiology, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://cvphysiology.com/blood-pressure/bp031

16. Pathophysiology of Hemorrhage as It Relates to the Warfighter | Physiology, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://journals.physiology.org/doi/10.1152/physiol.00028.2021

17. Clinical review: Hemorrhagic shock - PMC, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1065003/

18. Haemodynamic responses to acute blood loss: new roles for the heart, brain and endogenous opioids - PubMed, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2570536/

19. Anemia Screening - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499905/

20. Trauma's Lethal Triad of Hypothermia, Acidosis & Coagulopathy Create a Deadly Cycle for Trauma Patients - JEMS, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.jems.com/patient-care/emergency-trauma-care/trauma-s-lethal-triad-hypothermia-acidos/

21. Hemorrhagic Shock - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470382/

22. EMS Tactical Paramedic Lethal Triad - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK603758/

23. What is the lethal triad in trauma patients? - Dr.Oracle, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.droracle.ai/articles/289220/what-is-the-lethal-triad-in-trauma-patients-

24. Trauma triad of death - Wikipedia, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trauma_triad_of_death

25. Hypothermia in trauma - Emergency Medicine Journal, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://emj.bmj.com/content/30/12/989.abstract

26. Approach to the adult with anemia, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://doctorabad.com/uptodate/d/topic.htm?path=approach-to-the-adult-with-anemia

27. Anemia: Etiology, Pathophysiology, Impact, and Prevention: A Review - PMC, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12051798/

28. Anemia – Hemorrhage (Health Care / Medication Associated Condition): Introduction, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.healthcareexcellence.ca/en/resources/hospital-harm-is-everyones-concern/hospital-harm-improvement-resource/anemia-hemorrhage-hc-mac-introduction/

29. Acute Anaemia: A Challenging Diagnosis - PMC - NIH, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6346818/

30. Anemia - Causes and Risk Factors | NHLBI, NIH, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/anemia/causes

31. Postpartum Hemorrhage - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499988/

32. Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia (General Information) - Riverside MyChart, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://riversidemychart.org/MyChart-PRD/en-US/docs/Education/DischargeInstructions/Carenotes/cnen_metatags/ND9115G.HTM

33. Hemolytic Anemia: Symptoms, Treatment & Causes - Cleveland Clinic, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22479-hemolytic-anemia

34. Prenatal anemia and postpartum hemorrhage risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9258034/

35. Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH): Causes, Risks & Treatment - Cleveland Clinic, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22228-postpartum-hemorrhage

36. Postpartum Hemorrhage | Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/postpartum-hemorrhage

37. Postpartum Hemorrhage - Stanford Medicine Children's Health, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=postpartum-hemorrhage-90-P02486

38. Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia Treatment | Jersey Village, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.gastrodoxs.com/jerseyvillage/acute-posthemorrhagic-anemia

39. Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia: Symptoms, Causes, And Treatment - HealthMatch, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://healthmatch.io/anemia/acute-posthemorrhagic-anemia

40. Case Report: Effect of preventive intravenous iron infusion on postoperative hemoglobin levels in a female patient with latent i - Frontiers, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1586760/pdf

41. Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia Houston | D62 Code & Treatment - GastroDoxs, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.gastrodoxs.com/conditions/acute-posthemorrhagic-anemia

42. Anemia - Diagnosis and treatment - Mayo Clinic, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anemia/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20351366

43. Blood Transfusion - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499824/

44. Early Physiological Responses to Hemorrhagic Hypotension - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2900811/

45. Role of Interventional Radiology in the Emergent Management of ..., accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3577584/

46. Spontaneous Soft-Tissue Hemorrhage in Anticoagulated Patients: Safety and Efficacy of Embolization | AJR - American Journal of Roentgenology, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://ajronline.org/doi/10.2214/AJR.14.12578

47. Massive transfusion and massive transfusion protocol - PMC - PubMed Central - NIH, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4260305/

48. Anemia Practice Management Guidelines Anemia is a common clinical problem seen in critically ill trauma patients for a variety o, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.vumc.org/trauma-and-scc/sites/default/files/public_files/Protocols/Anemia%20Practice%20Management%20Guideline.pdf

49. Surviving Extreme Anaemia - PMC - NIH, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8046282/

50. Management of Hemorrhagic Shock: Physiology Approach, Timing and Strategies - MDPI, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/12/1/260

51. Role of interventional radiology in the management of acute gastrointestinal bleeding, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261957081_Role_of_interventional_radiology_in_the_management_of_acute_gastrointestinal_bleeding

52. Interventional therapy for acute hemorrhage in gastrointestinal tract - PMC, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4077477/

53. Interventional radiology treatments for iatrogenic severe bleeding ..., accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6323580/

54. Bleeding Complications in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.imrpress.com/journal/RCM/23/8/10.31083/j.rcm2308286/htm

55. The importance of intensive follow-up and achieving optimal chronic antithrombotic treatment in hospitalized medical patients with anemia: A prospective cohort study - PubMed, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38176585/

56. Massive Transfusion - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499929/

57. Massive transfusion complications | Australian Red Cross Lifeblood, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.lifeblood.com.au/health-professionals/clinical-practice/adverse-events/massive-transfusion-complications

58. Massive Hemorrhage Protocols 2.0 - Emergency Medicine Cases, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://emergencymedicinecases.com/massive-hemorrhage-protocols-2-0/

59. Multidisciplinary consensus document on the management of massive haemorrhage (HEMOMAS document) | Medicina Intensiva, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.medintensiva.org/en-multidisciplinary-consensus-document-on-management-articulo-S2173572715000636

60. How to write a systematic literature review [9 steps] - Paperpile, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://paperpile.com/g/systematic-literature-review/

61. Key Steps in a Literature Review - UWSOM Intranet, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://education.uwmedicine.org/curriculum/medical-student-scholarship/starthere/scholarship-of-integration/literature-review/

62. Chapter 9 Methods for Literature Reviews - Handbook of eHealth Evaluation - NCBI, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481583/

63. Prediction of massive bleeding in a prehospital setting: Validation of ..., accessed on October 24, 2025, https://medintensiva.org/en-prediction-massive-bleeding-in-prehospital-articulo-S2173572719300244

64. Early Prediction of Ongoing Hemorrhage in Severe Trauma: Presentation of the Existing Scoring Systems - PMC, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5251191/

65. Comparison of different scoring systems in predicting the need for blood transfusion in emergency department - Archives of Trauma Research, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://archtrauma.kaums.ac.ir/article_210898_213d85464c2e7951f8d9de8d19ea243c.pdf

66. How I treat patients with massive hemorrhage | Blood | American Society of Hematology, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/124/20/3052/33229/How-I-treat-patients-with-massive-hemorrhage

67. A comparison of risk prediction models for patients with acute coronary syndromes, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://eurointervention.pcronline.com/article/a-comparison-of-risk-prediction-models-for-patients-with-acute-coronary-syndromes

68. Machine Learning–Based Prediction for In‐Hospital Mortality After Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage Using Real‐World Clinical and Image Data, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.124.036447

69. Clinical Approach to and Work-up of Bleeding Patients - PMC - NIH, accessed on October 24, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7056343/