Local anesthesia. Regional anesthesia: Spinal and Epidural Anesthesia

1. Syed Ali Abbas Rahat

2. Kurmanaliev Nurlanbek

3. Akash Soni

Anas Khan

Tapish Panwar

Subhash Kumar Verma

Charul Sharma

Zishan Uddin

Talib Ansari

Kajal khan

(1. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic

2. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic

3. Students, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic)

Abstract

Anesthesia has transformed surgical practice by enabling pain-free procedures and improving patient safety. Local anesthesia induces temporary loss of sensation in a limited area, while regional anesthesia affects larger regions of the body, sometimes including motor blockade. Among regional anesthesia techniques, spinal and epidural anesthesia are widely utilized for lower abdominal, pelvic, and lower limb surgeries. This review presents a comprehensive discussion of local and regional anesthesia, with a focus on spinal and epidural anesthesia. It examines their history, pharmacology, mechanisms of action, clinical applications, advantages, limitations, complications, and recent advancements in practice. The review emphasizes the importance of these anesthetic techniques in modern surgical and perioperative care.

Keywords: Local anesthesia, Regional anesthesia, Spinal anesthesia, Epidural anesthesia, Surgical anesthesia, Pain management, Pharmacology

Introduction

The ability to provide anesthesia is one of the most significant milestones in the history of medicine. Before the advent of anesthesia, surgery was associated with extreme pain and significant physiological stress. Over the centuries, local and regional anesthesia techniques have evolved to provide effective pain control while minimizing systemic risks. Local anesthesia allows surgeons to perform minor procedures without affecting consciousness, whereas regional anesthesia provides more extensive analgesia and is indispensable for major surgeries involving the lower abdomen, pelvis, and lower limbs.

The use of spinal and epidural anesthesia has become standard practice in many surgical specialties, including obstetrics, urology, orthopedics, and general surgery. Their increasing popularity is due to their efficacy, safety, and ability to improve postoperative recovery. In this article, the historical development, pharmacology, physiology, clinical applications, complications, and recent advancements in local and regional anesthesia are explored in detail.

Historical Perspective

Local anesthesia has a rich history dating back to the use of coca leaves in South America for pain relief. In 1884, Carl Koller, an Austrian ophthalmologist, first demonstrated the use of cocaine as a local anesthetic in eye surgery. Soon after, synthetic local anesthetics such as procaine were developed, offering safer and more predictable results. The 20th century saw the development of amide local anesthetics like lidocaine and bupivacaine, which remain widely used today.

Regional anesthesia techniques, particularly spinal and epidural anesthesia, were pioneered in the early 20th century. August Bier performed the first spinal anesthesia in 1898, and the use of epidural anesthesia gained popularity in the 1930s. Over time, these techniques have been refined, with improvements in drug formulations, needle designs, and safety protocols.

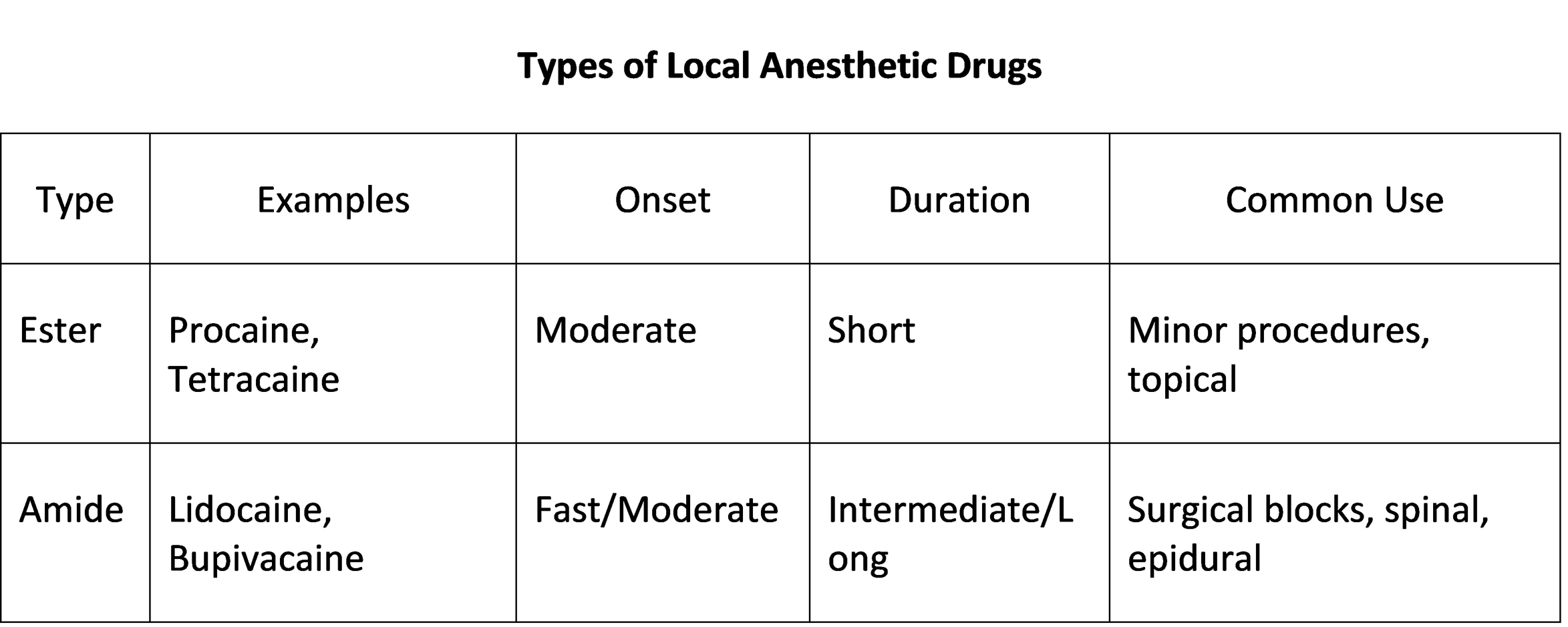

Local Anesthesia

Local anesthesia refers to the reversible loss of sensation in a specific area without affecting consciousness. It is achieved by administering anesthetic drugs through topical application, infiltration, or peripheral nerve blocks. Local anesthetics act by blocking voltage-gated sodium channels in nerve membranes, preventing depolarization and conduction of nerve impulses. This interruption inhibits the transmission of pain signals to the central nervous system.

The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of local anesthetics influence their clinical use. Factors such as lipid solubility, protein binding, and pKa determine the onset, duration, and potency of each drug. Lidocaine is favored for procedures requiring rapid onset, whereas bupivacaine provides prolonged analgesia. Vasoconstrictors like epinephrine are sometimes added to prolong the anesthetic effect and minimize bleeding, though their use is contraindicated in areas supplied by end arteries.

Local anesthesia is applied in a variety of clinical contexts, including suturing, abscess drainage, minor excisions, dental procedures, and skin biopsies. Advantages include minimal systemic effects, rapid recovery, cost-effectiveness, and patient cooperation. Complications are uncommon but may include allergic reactions, hematoma formation, and systemic toxicity when administered in excessive doses.

Regional Anesthesia

Regional anesthesia involves the targeted blockade of nerve conduction in a larger area than local anesthesia, often resulting in both sensory and motor blockade. Patients remain conscious while experiencing effective pain relief. This technique is advantageous in surgeries requiring profound analgesia, reduced opioid consumption, and preservation of physiological function.

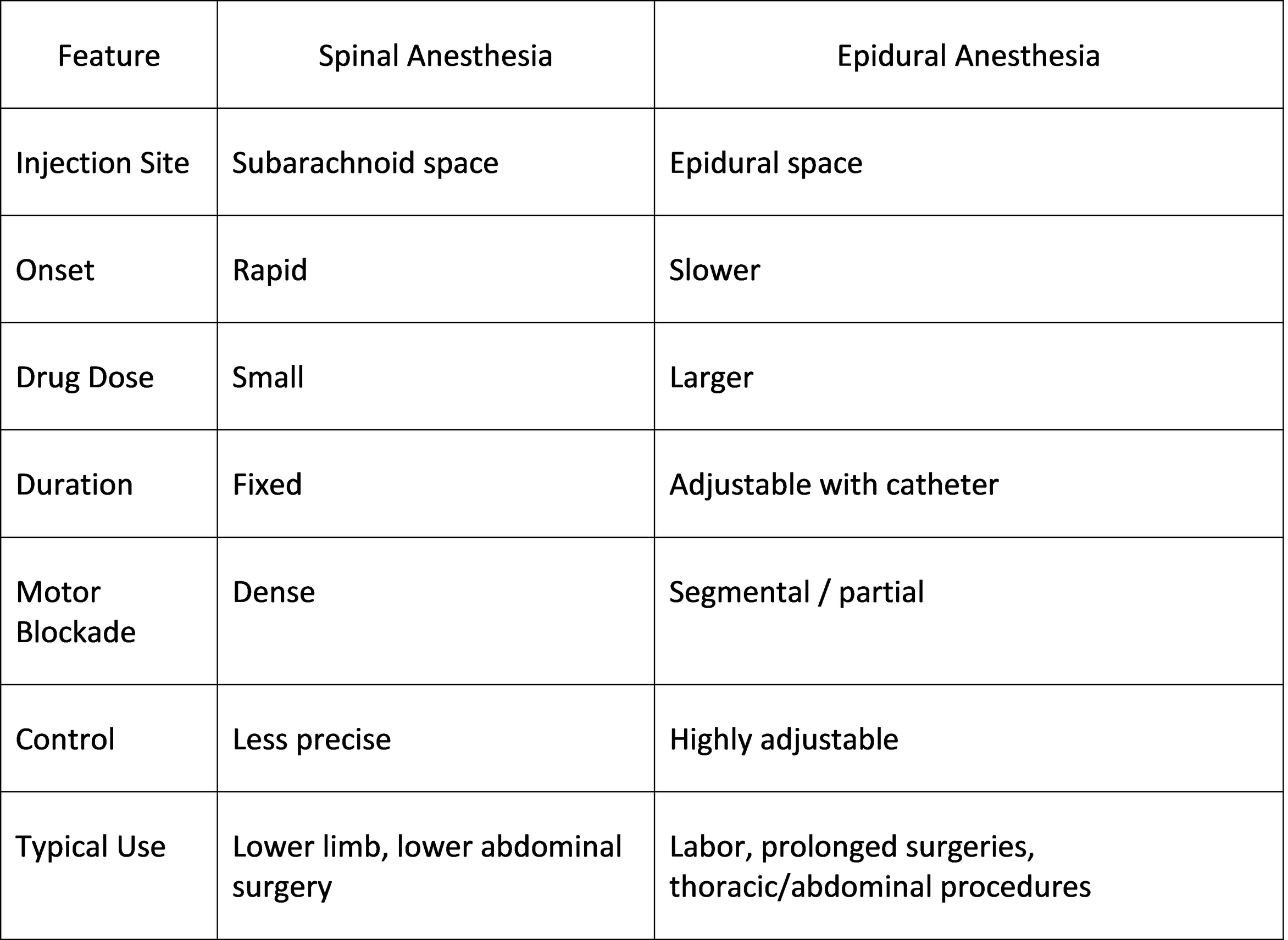

Spinal and epidural anesthesia are the most frequently used regional anesthesia techniques in surgical practice. Spinal anesthesia provides dense sensory and motor blockade, whereas epidural anesthesia allows adjustable segmental blockade. These techniques are integral to modern perioperative care and are widely incorporated into Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols.

Spinal Anesthesia

Spinal anesthesia involves the injection of a local anesthetic into the subarachnoid space, where it mixes with cerebrospinal fluid. The injection is usually performed at the L3–L4 or L4–L5 intervertebral space, below the termination of the spinal cord in adults, ensuring safety. The anesthetic drug blocks sensory, motor, and sympathetic fibers, producing a complete loss of sensation and muscle relaxation in the targeted region.

The distribution and duration of spinal anesthesia depend on factors such as anesthetic dose, baricity, patient position, and anatomical variations. It is commonly employed for lower abdominal, pelvic, urological, and lower limb orthopedic surgeries, as well as cesarean sections.

Clinical Considerations of Spinal Anesthesia

The anesthesiologist must consider patient positioning, baricity of the anesthetic solution, and contraindications, which include infection at the puncture site, coagulopathy, severe hypovolemia, or patient refusal. Complications such as hypotension, bradycardia, post-dural puncture headache, nausea, urinary retention, or rare neurological injury may occur but are manageable with appropriate monitoring and interventions.

Epidural Anesthesia

Epidural anesthesia entails the injection of a local anesthetic into the epidural space, outside the dura mater. A catheter may be placed for continuous or intermittent administration, allowing prolonged analgesia. The anesthetic drug diffuses across the dura to block spinal nerve roots selectively, producing segmental anesthesia. Epidural anesthesia allows modulation of sensory and motor blockade, offering flexibility during surgery or labor.

Epidural anesthesia is extensively used for labor analgesia, lower abdominal and thoracic surgeries, postoperative pain management, and chronic pain control. Its benefits include adjustable dosing, stable hemodynamics, preservation of respiratory function, and effective pain control without significant systemic effects.

Comparison: Spinal vs Epidural Anesthesia

Physiological Basis and Pharmacology

Local and regional anesthetics act primarily on voltage-gated sodium channels, preventing depolarization of nerve fibers. Sensory fibers are more sensitive to blockade than motor fibers due to differences in fiber diameter and myelination. Sympathetic fibers are also affected, often leading to vasodilation and hypotension. The onset and duration of action depend on drug properties, tissue pH, vascularity, and adjunctive agents such as vasoconstrictors. Amide anesthetics are metabolized in the liver, while ester anesthetics are hydrolyzed by plasma cholinesterases. Awareness of metabolism is critical for dose adjustment in patients with hepatic or renal impairment to prevent systemic toxicity.

Complications and Management

Although generally safe, spinal and epidural anesthesia may produce complications. Hypotension and bradycardia are common due to sympathetic blockade. Post-dural puncture headache can occur after spinal anesthesia, while epidural hematoma, infection, or incomplete block may complicate epidural anesthesia. Proper technique, patient monitoring, and prompt management minimize risks. Rare neurological injuries are exceptional but highlight the importance of experienced practitioners.

Recent Advances

Recent developments in anesthesia include newer local anesthetics with improved safety profiles, adjuvant drugs enhancing analgesia, ultrasound-guided nerve blocks for precision, and integration of regional anesthesia into ERAS protocols. Continuous spinal or epidural techniques allow prolonged analgesia with adjustable dosing. These advances improve patient outcomes, reduce opioid requirements, and enhance recovery.

Conclusion

Local and regional anesthesia are essential components of contemporary surgical practice. Local anesthesia is suitable for minor procedures, while spinal and epidural anesthesia provide safe and effective anesthesia for major surgeries involving the lower body. Understanding the pharmacology, physiology, and clinical application of these techniques ensures optimal patient care. Continuous advances in anesthetic drugs and techniques, combined with meticulous clinical practice, reinforce the pivotal role of these methods in modern surgery and perioperative management.

References

Mayorga DE, et al. Local and Regional Anesthesia: Clinical Considerations. Int J Med Sci Clin Res Stud. 2022;2(08):834–836. https://doi.org/10.47191/ijmscrs/v2-i8-20

Torpy JM, Lynm C, Golub RM. Regional Anesthesia. JAMA. 2013. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1104234

Local Anesthetics & Regional Anesthesia. LearnAnesthesia.org. https://learnanesthesia.org/local-anesthetics-regional-anesthesia/

StatPearls. Spinal Anesthesia. NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537299/

StatPearls. Epidural Anesthesia. NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542219/

Buerkle H, et al. Regional anesthesia: spinal and epidural application. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2000;14(2):393‑409. https://doi.org/10.1053/bean.2000.0095

Lambert DH. Local Anesthetic Pharmacology. Springer, 1994. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-011-0816-4_3

Neuraxial blockade. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuraxial_blockade

Cambridge University Press. Fundamentals of Regional Anaesthesia. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108876902.019