Pediatric Diabetes Mellitus: Etiology, Management, and Future Directions

1. Md Reyaz Alam

2. Osmonova G. Zh.

(1. Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.

2. Teacher, Dept. of Pediatrics, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.)

Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) in children represents a significant and growing public health challenge globally. While Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) remains the most prevalent form in childhood, the incidence of Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) and other forms is rising alarmingly, paralleling trends in childhood obesity. This article provides a comprehensive review of pediatric diabetes, adhering to the IMRAD structure. It explores the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and distinct clinical presentations of the main diabetes types affecting children. A detailed analysis of current management paradigms is presented, emphasizing the importance of intensive, family- centered glycemic control to prevent acute and chronic complications. The article further discusses the profound psychosocial impact of a chronic disease diagnosis in childhood and adolescence. Finally, it examines emerging technologies and therapies, identifying critical gaps in research and public policy. The conclusion synthesizes the state of the field, underscoring the necessity for early detection, multidisciplinary care, and sustained research to improve long-term outcomes for children living with diabetes.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by chronic hyperglycemia resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. Its manifestation in children and adolescents presents unique clinical, developmental, and psychosocial challenges distinct from adult-onset disease. Historically, diabetes diagnosed in childhood was al- most exclusively autoimmune Type 1 diabetes. However, the 21st century has witnessed a dramatic epidemiological shift, with a marked increase in cases of Type 2 diabetes, mono- genic diabetes (e.g., MODY), and other forms in pediatric populations.

The global burden is substantial. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), approximately 1.2 million children and adolescents under 20 live with Type 1 diabetes, with around 164,000 new cases diagnosed annually. The incidence of T1D is increasing by 3-4% per year in many countries, particularly in younger children. Con- currently, the rise in childhood obesity has precipitated an epidemic of T2D in youth, a disease once termed adult-onset. In the United States, the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study found that from 2002 to 2018, the estimated prevalence of T1D increased by 45.1% and of T2D by an alarming 95.3%.

This epidemiological transition complicates diagnosis and management. Differentiating between T1D, T2D, and monogenic diabetes is crucial for appropriate therapy but can be challenging due to overlapping phenotypes, particularly in obese adolescents. Misdiagnosis leads to suboptimal treatment and worse outcomes. Furthermore, the management of a lifelong chronic condition during critical periods of physical, cognitive, and emotional development requires a tailored, multidisciplinary approach.

The primary aims of this article are to: 1) delineate the classification, etiology, and clinical presentation of diabetes in children; 2) review evidence-based management strategies from diagnosis to long-term care; 3) analyze the acute and chronic complications associated with pediatric diabetes; and 4) explore the psychosocial dimensions and future directions in research and care. This synthesis aims to provide a foundational resource for clinicians, researchers, and students involved in pediatric diabetology.

Methods

This article is based on a comprehensive narrative review of the scientific literature. A systematic search was conducted using major electronic databases, including PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library, for publications from January 2010 to December 2023. Key search terms included: “pediatric diabetes”, childhood diabetes mellitus, type 1 diabetes children, type 2 diabetes adolescents, monogenic diabetes, diabetic ketoacidosis pediatric, continuous glucose monitoring children, psychosocial impact diabetes children, and diabetes technology pediatric. Priority was given to meta- analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), large cohort studies (e.g., SEARCH, DCCT/EDIC, TODAY), and consensus guidelines from professional bodies such as the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD), the American Diabetes Association (ADA), and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). References from identified articles were also hand-searched for additional relevant sources. Data on epidemiology, diagnostic criteria, treatment protocols, and out- comes were extracted, analyzed, and synthesized to present a current and evidence- based overview of the field.

Results

Classification and Pathophysiology

Pediatric diabetes is not a homogenous entity. Accurate classification guides management and prognostic counseling.

Type 1 Diabetes (T1D): T1D is an organ-specific autoimmune disease. Genetic susceptibility, particularly within the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region, interacts with poorly defined environmental factors (e.g., enteroviral infections, early diet, vita- min D) to trigger an immune-mediated destruction of insulin-producing pancreatic -cells. This process leads to an absolute insulin deficiency. Islet autoantibodies—such as glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), insulinoma-associated-2 (IA-2), and zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8)— are serological markers of this autoimmune process and are present in over 90% of individuals at diagnosis.

Type 2 Diabetes (T2D): T2D in youth is characterized by a combination of insulin resistance and progressive -cell failure. The pathophysiology is driven predominantly by obesity, which induces chronic low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance in muscle, liver, and adipose. The pancreatic-cells initially compensate by secreting more (hyperinsulinemia), but eventually fail to meet demand, leading to relative insulin deficiency and hyperglycemia. Puberty exacerbates insulin resistance due to growth hormone surges. Unlike T1D, autoimmune markers are absent.

Monogenic Diabetes: Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY) is the most common form, caused by heterozygous mutations in genes critical for -cell function (e.g., HNF1A, GCK, HNF4A). It is often misdiagnosed as T1D or T2D. Correct diagnosis is critical as it often dictates specific therapy; for example, individuals with HNF1A-MODY are exquisitely sensitive to sulfonylureas.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

The clinical presentation varies by type but often overlaps. T1D: Presentation is often acute and severe. Classic symptoms include polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss despite polyphagia, and fatigue. Approximately 30-40% of children present with Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA), a life-threatening emergency characterized by hyperglycemia (¿200 mg/dL), metabolic acidosis (pH ¡7.3, bicarbonate ¡15 mmol/L), and ketonemia. DKA is more common in younger children and those with delayed diagnosis.

T2D: Onset is typically more insidious. Many children are asymptomatic and diagnosed through screening (e.g., due to obesity or acanthosis nigricans—a dark, velvety skin hyperpigmentation). Others may present with mild polyuria/polydipsia or, less commonly, with DKA or Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State (HHS), which carries a high mortality risk.

Diagnostic Criteria: The diagnosis is confirmed by meeting any one of the following ADA criteria: 1) Fasting plasma glucose 126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L); 2) 2-hour plasma glucose 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) during an oral glucose tolerance test; 3) HbA1c 6.5% (48 mmol/mol); or 4) In a patient with classic hyperglycemic symptoms, a random plasma glucose 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L). Autoantibody testing (for T1D) and genetic testing (if MODY is suspected) are essential for accurate classification.

Management Principles

Management is complex, lifelong, and requires a family-centered, multidisciplinary team.

Insulin Therapy for T1D: Insulin replacement is life-saving. Regimens aim to mimic physiological secretion:

• Basal-Bolus Regimen: The gold standard. Involves once- or twice-daily long- acting (basal) insulin (e.g., glargine, detemir, degludec) to control background glucose, plus rapid-acting insulin (e.g., lispro, aspart, glulisine) injected at mealtimes (bolus) to cover carbohydrates and correct hyperglycemia.

• Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion (CSII/Insulin Pump): Delivers rapid-acting insulin continuously via a cannula. Allows for precise dosing, temporary basal rate adjustments, and is associated with improved glycemic control and quality of life in many patients.

• Calculating Doses: Doses are weight-based initially (e.g., 0.5-1.0 U/kg/day), then titrated based on frequent glucose monitoring, carbohydrate intake, and physical activity.

Management of T2D in Youth: First-line therapy is intensive lifestyle modification, focusing on weight management through structured nutrition and 60 minutes of daily physical activity. Pharmacotherapy is initiated if glycemic targets are not met. Metformin is the first-line oral agent. Insulin is used if presented with ketosis/severe hyperglycemia. Newer classes like GLP-1 receptor agonists (e.g., liraglutide) are now approved for use in adolescents and show efficacy.

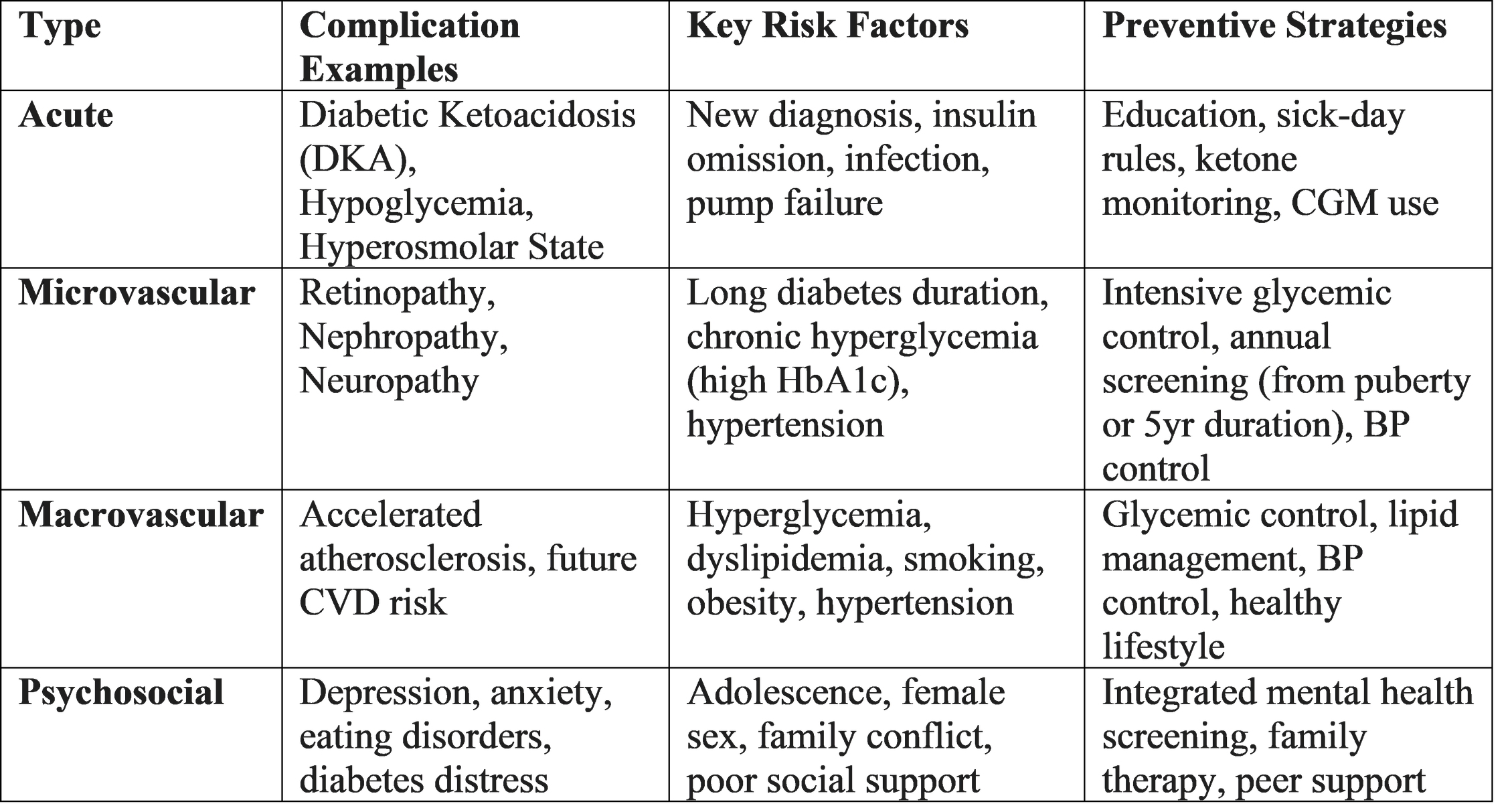

Complications

The landmark Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) and its follow-up Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study irrefutably proved that intensive glycemic control (median HbA1c 7%) in adolescence and young adulthood dramatically reduces the long-term risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications.

Psychosocial and Family Impact

A pediatric diabetes diagnosis affects the entire family. Management demands constant vigilance, disrupting normal childhood activities. Diabetes distress—the emotional burden of relentless self-care—is common in parents and adolescents. Adolescents face unique challenges: striving for autonomy while managing a complex regimen, peer pressure, and risk-taking behaviors. Disordered eating behaviors and diabulimia (intentional insulin omission for weight loss) are serious, under-recognized complications, particularly in adolescent females. Integrated mental health support is a non-negotiable component of comprehensive care.

Discussion

The landscape of pediatric diabetes is evolving rapidly. The sharp rise in T2D incidence is a direct consequence of the global childhood obesity epidemic and represents a failure of public health policy. Youth-onset T2D appears more aggressive than adult-onset, with faster - cell decline and higher complication rates, as demonstrated by the TODAY study, which showed a high rate of treatment failure and early complications. This demands urgent population-level interventions targeting obesity prevention.

The paradigm for T1D management has shifted from mere survival to optimization of health and quality of life through technology. CGM and AID systems represent the most significant advance since the discovery of insulin. However, equity of access remains a major concern; these technologies are expensive and often unavailable in low-resource settings, potentially widening outcome disparities. Accurate diagnosis remains a clinical cornerstone.

The overlap in phenotypes, especially in an obese adolescent presenting with ketosis, can lead to misclassification. A low threshold for autoantibody and, where indicated, genetic testing is essential. Mono- genic diabetes, though rare, is likely underdiagnosed, and its identification can transform management.

Psychosocial support must be destigmatized and embedded within routine care. The relentless demands of diabetes management can lead to burnout for both child and care- giver. Future care models must prioritize mental health with the same vigor as glycemic metrics. Furthermore, transition from pediatric to adult healthcare is a vulnerable period associated with lapses in care; structured transition programs are vital for continuity.

Several key research gaps persist: 1) The precise environmental triggers for T1D autoimmunity; 2) More effective and durable pharmacotherapies for youth-onset T2D; 3) Strategies to prevent or delay the onset of T1D in at-risk individuals (building on successes like teplizumab); 4) Making diabetes technology affordable and accessible globally; and 5) Developing interventions to mitigate diabetes distress and improve resilience.

Conclusion

Diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents is a complex, chronic disease with a rising global prevalence and significant personal and societal costs. Its etiology is diverse, encompassing autoimmune, metabolic, and genetic forms, each requiring a distinct management approach. The cornerstone of care remains achieving optimal glycemic control through intensive, individualized regimens—now powerfully augmented by continuous glucose monitoring and automated insulin delivery systems—to prevent both acute crises and long-term debilitating complications. However, technological advancement alone is insufficient. Effective management must be delivered within a holistic, family-centered framework that addresses the profound psychosocial impact of the disease. The rising tide of type 2 diabetes in youth serves as a stark warning, highlighting the critical need for effective public health strategies to combat childhood obesity. Future efforts must focus on closing research gaps, ensuring equitable access to innovations, and developing sustainable, compassionate models of care that support children with diabetes not just to survive, but to thrive throughout their lives. The ultimate goal is to mitigate the burden of this lifelong condition until the day a true cure is found.

References

Atkinson, M. A., Eisenbarth, G. S., & Michels, A. W. (2014). Type 1 diabetes. The Lancet, 383(9911), 69–82.

Brown, S. A., et al. (2019). Six-month randomized, multicenter trial of closed-loop control in type 1 diabetes. The New England Journal of Medicine, 381, 1707–1717.

Dabelea, D., et al. (2010). Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, 39(3), 481–497.

Dabelea, D., et al. (2014). Prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among children and adolescents from 2001 to 2009. JAMA, 311(17), 1778–1786.

DCCT/EDIC Research Group. (2016). Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular outcomes in type 1 diabetes: The DCCT/EDIC study 30-year follow-up. Diabetes Care, 39(5), 686–693.

International Diabetes Federation. (2021). IDF Diabetes Atlas (10th ed.). https://www.diabetesatlas.org

Lawrence, J. M., et al. (2021). Trends in prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents in the US, 2001-2017. JAMA, 326(8), 717–727.

TODAY Study Group. (2012). A clinical trial to maintain glycemic control in youth with type 2 diabetes. The New England Journal of Medicine, 366, 2247–2256.

TODAY Study Group. (2021). Long-term complications in youth-onset type 2 diabetes. The New England Journal of Medicine, 385, 416–426.

Wolfsdorf, J. I., et al. (2022). Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state: A consensus statement from the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes, 23(7), 835–856.

Zeitler, P., et al. (2016). Youth-onset type 2 diabetes consensus report: Current status, challenges, and priorities. Diabetes Care, 39(9), 1635–1642.