Pituitary Dwarfisim in Pediatrics

1. Gulnaz Osmonova

2. Sachin Tiwari

(1. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic

2.Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic)

Abstract

Pituitary dwarfism in children, also commonly referred to as childhood growth hormone deficiency (GHD) or hypopituitarism, represents a spectrum of disorders characterized by insufficient secretion or action of growth-promoting hormones. Although rare, it is clinically significant due to its impact on height, pubertal development, metabolic function, and quality of life. This article synthesizes current knowledge of growth patterns, endocrine profiles, diagnostic approaches, treatment strategies, long-term outcomes, and real-world clinical scenarios in pediatric pituitary dwarfism, aiming to support both clinicians and learners in evidence-based pediatric endocrinology.

Keywords

Pituitary dwarfism, growth hormone deficiency (GHD), pediatric endocrinology, short stature, isolated growth hormone deficiency (IGHD), multiple pituitary hormone deficiency (MPHD), growth hormone therapy, recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH), IGF‑1, bone age, pubertal delay, Laron syndrome, hormonal profile, pituitary imaging, pediatric growth disorders.

Introduction

Pituitary dwarfism, also known as growth hormone deficiency (GHD), is a rare endocrine disorder in children that leads to impaired growth and short stature. It occurs when the pituitary gland fails to produce sufficient growth hormone, either in isolation (isolated GHD) or alongside deficiencies of other pituitary hormones (multiple pituitary hormone deficiency, MPHD). While the condition is uncommon, early recognition is essential because untreated children often remain significantly shorter than their peers and may experience delays in puberty and subtle metabolic disturbances.

Growth hormone plays a central role in stimulating bone growth and maintaining normal body composition during childhood. Children with pituitary dwarfism typically appear healthy at birth, as fetal growth relies less on GH, but growth gradually slows over the first few years of life. Other features, such as delayed bone age and proportionate short stature, often raise clinical suspicion. Advances in diagnostic techniques, including hormone stimulation tests, IGF‑1 measurement, and pituitary imaging, allow precise identification of affected children. With modern recombinant growth hormone therapy, most children can achieve near-normal adult height and improved quality of life. Early diagnosis and individualized treatment are therefore critical for optimal outcomes.

Epidemiology and Natural History

Pituitary dwarfism, caused primarily by growth hormone deficiency (GHD), is a rare condition in children but represents a significant cause of short stature when it occurs. The incidence of congenital GHD is estimated at about 1 in 4,000 to 1 in 10,000 live births, while acquired forms, due to tumors, trauma, infections, or cranial irradiation, are less common but increasingly recognized with modern imaging and cancer treatments. Both boys and girls can be affected, although some studies suggest a slight male predominance in isolated forms.

The natural history of pituitary dwarfism depends on whether the deficiency is isolated or part of multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies (MPHD). Children with isolated GHD often appear normal at birth, as fetal growth is largely independent of GH. Growth failure becomes apparent in early childhood, typically around 1–3 years of age, as their height velocity falls below expected norms. Without treatment, these children may reach an adult height that is significantly below the population average.

In contrast, MPHD usually presents earlier and with more severe symptoms because multiple hormones regulating growth, metabolism, and puberty are affected. These children may experience hypoglycemia, fatigue, delayed puberty, and other systemic symptoms alongside poor growth. Acquired GHD may develop after injury, surgery, tumors, or radiation affecting the hypothalamic-pituitary region.

Certain genetic syndromes, such as mutations affecting GH production or receptor function, can result in lifelong growth failure if untreated. Historical studies show that untreated children often maintain proportionate short stature, delayed bone age, and delayed puberty, but their cognitive development is usually normal.

Growth Patterns

Human growth occurs in four phases—fetal, infancy, childhood, and puberty—each influenced by specific endocrine and environmental factors. The GH-IGF axis is critical during childhood and puberty, while thyroid hormone and nutrition dominate earlier growth phases.

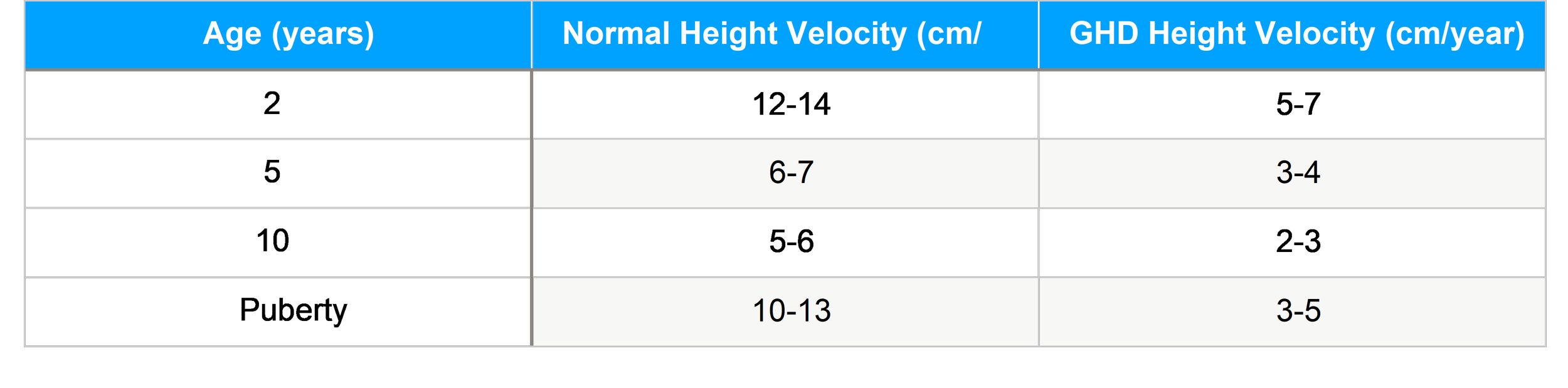

Typical Growth Trajectory in GHD Children with pituitary dwarfism exhibit:

Subnormal growth velocity Delayed bone age

Height sitting well below age-matched norms

Delayed pubertal milestones (depending on additional hormone deficiencies)

1. Hormonal Profiles and Diagnostic Evaluation

Accurate endocrine evaluation is central in diagnosing pituitary dwarfism.

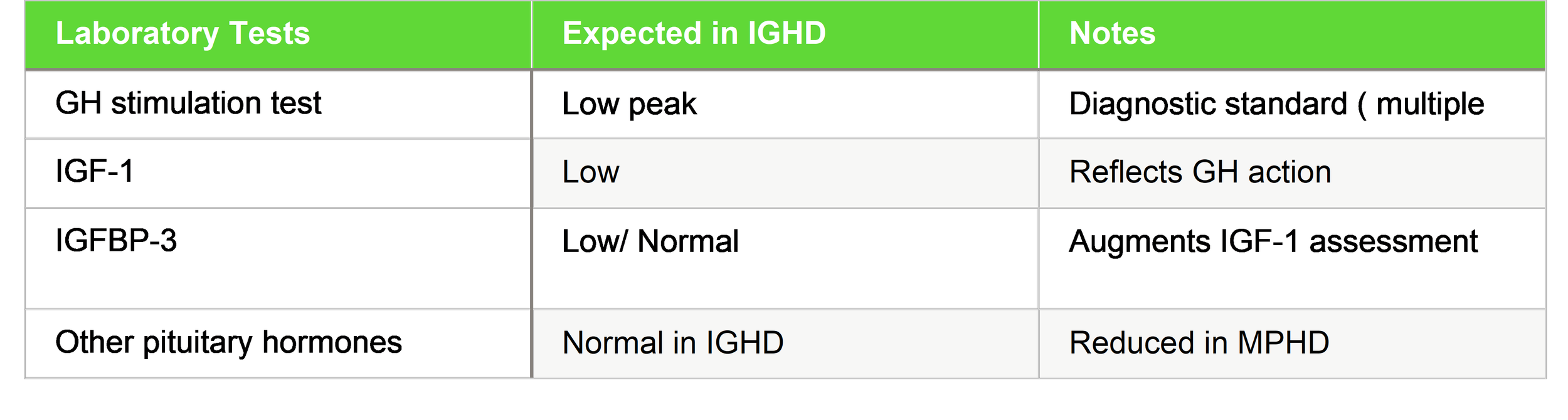

1.1 Laboratory Assessment

Key hormones assessed:

IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 are commonly used biochemical markers in monitoring GH status (used in clinical studies to track responses).

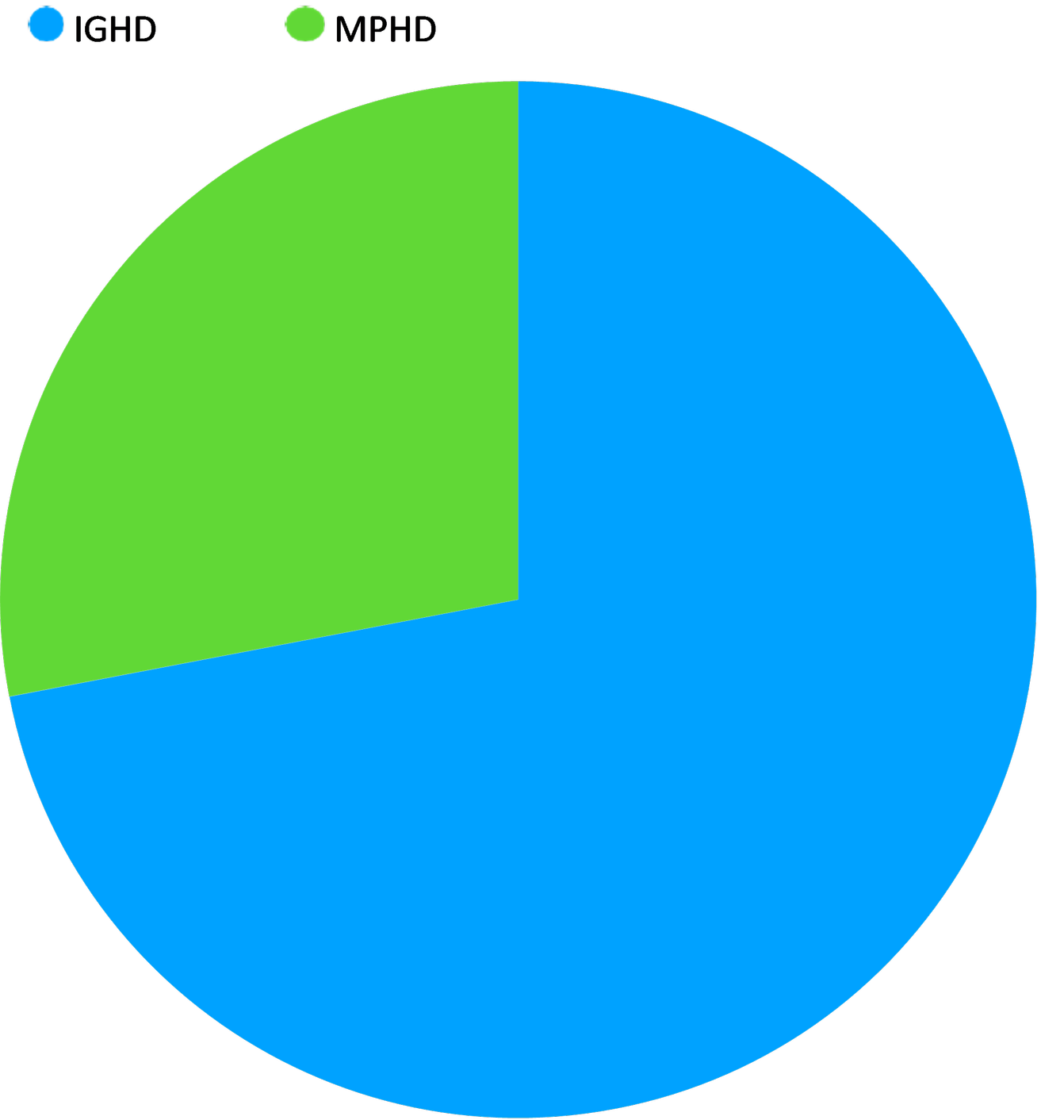

Hormonal Profile Distribution :(Pie Chart)

This chart illustrates the common clinical distribution of growth hormone deficiency (GHD) in pediatric patients.

Isolated GH Deficiency (IGHD): Approximately 72% of cases involve only the growth hormone. This is often idiopathic (unknown cause) or genetic.

Multiple Pituitary Hormone Deficiencies (MPHD): Approximately 28% of patients exhibit deficiencies in other pituitary hormones (such as TSH, ACTH, or gonadotropins). This is more common in cases involving structural abnormalities like pituitary stalk interruption or brain tumors.

Clinical Subtypes and Profiles

Isolated Growth Hormone Deficiency (IGHD)

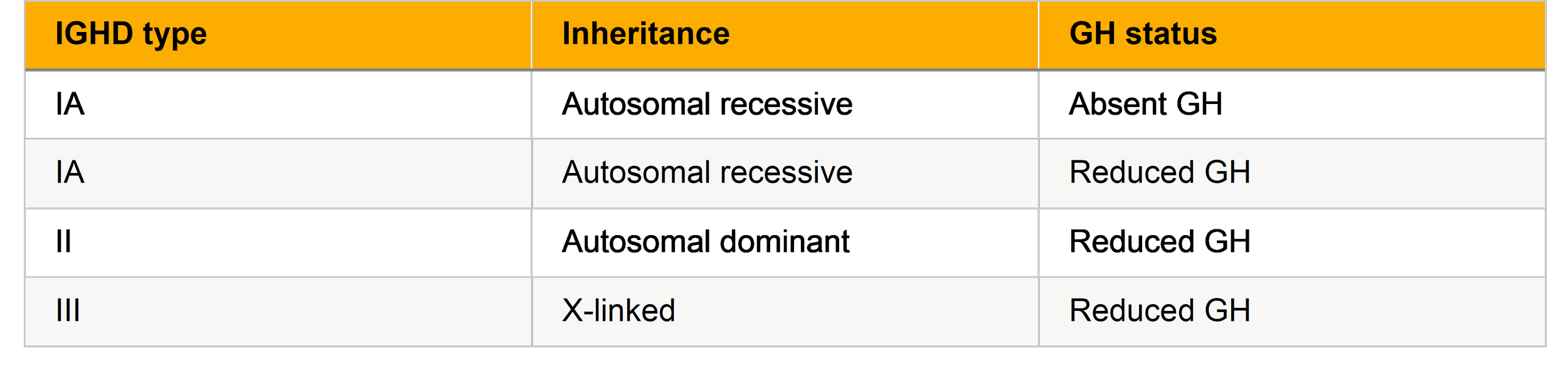

IGHD has subtypes based on genetic and clinical severity:

Multiple Pituitary Hormone Deficiency (MPHD)

MPHD includes deficiencies of GH plus other pituitary hormones such as TSH, ACTH, and gonadotropins. Patients typically present earlier with more severe growth failure and require comprehensive hormone replacement.

GH Insensitivity Syndromes

Laron syndrome is the prototypical GH insensitivity disorder characterized by:

High GH, low IGF-1 Severe short stature Obesity tendency

Resistance to standard GH therapy IGF-1 treatment indicated instead

Pituitary dwarfism in children encompasses a spectrum of disorders primarily caused by growth hormone deficiency (GHD), either in isolation or as part of multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies (MPHD). Accurate identification of clinical subtypes is essential for prognosis, genetic counseling, and tailored treatment.

1. Isolated Growth Hormone Deficiency (IGHD):This is the most common form and involves selective deficiency of GH with otherwise normal pituitary function. IGHD can be further classified into genetic subtypes:

Type IA (autosomal recessive): Complete absence of GH, usually presents in infancy with severe growth failure and very low IGF‑1 levels.

Type IB (autosomal recessive): Partial GH deficiency with variable growth impairment; milder clinical presentation than IA.

Type II (autosomal dominant): Often presents later in childhood, with gradual growth deceleration. Type III (X-linked): Rare, often associated with familial patterns and mild growth delay.

Children with IGHD typically have proportionate short stature, delayed bone age, normal cognitive development, and delayed puberty depending on age of diagnosis. Early initiation of GH therapy often results in marked catch-up growth.

Multiple Pituitary Hormone Deficiency (MPHD):

MPHD involves GH deficiency along with other pituitary hormone deficits, such as TSH, ACTH, or gonadotropins. Clinically, these children present earlier with more severe growth retardation and may exhibit systemic symptoms like fatigue, hypoglycemia, or cold intolerance due to hypothyroidism or adrenal insufficiency. MRI often shows pituitary hypoplasia or structural abnormalities. Management requires comprehensive hormonal replacement in addition to GH therapy.

2. Growth Hormone Insensitivity (Laron Syndrome):

A distinct subtype, characterized by elevated GH levels but very low IGF‑1 due to GH receptor defects. Children have severe short stature, characteristic facial features, obesity, and do not respond to GH therapy; recombinant IGF‑1 is the treatment of choice.

3. Syndromic or Acquired Forms:

Other less common subtypes include children with structural pituitary defects, tumors, cranial irradiation, or post-traumatic hypopituitarism, which can mimic congenital forms but often present with additional neurological or endocrine symptoms.

Diagnostic Protocol and Clinical Algorithm

Initial Evaluation (Detailed growth history Growth chart plotting

Bone age assessment Serum IGF-1 & IGFBP-3

GH stimulation tests with at least two agents)

Imaging

(MRI evaluation of the pituitary and hypothalamus detects structural abnormalities such as pituitary hypoplasia or ectopic posterior pituitary.)

The diagnosis of pituitary dwarfism, or growth hormone deficiency (GHD), is primarily based on clinical, auxological, biochemical, and imaging assessments. Clinically, affected children present with proportionate short stature, reduced growth velocity, and delayed bone age, while other physical features such as facial appearance are usually normal. Growth charts are essential for monitoring height over time and identifying deviations from expected trajectories.

Biochemical evaluation focuses on the GH–IGF axis. Random GH levels are unreliable due to pulsatile secretion, so GH stimulation tests using agents like insulin, clonidine, arginine, or glucagon are performed. A subnormal GH peak (commonly <7–10 ng/mL) confirms deficiency. Serum IGF‑1 and IGFBP‑3 levels are typically low and provide supportive evidence of impaired GH action. In cases of multiple pituitary hormone deficiency (MPHD), additional hormonal assays including thyroid hormones, cortisol, and gonadotropins help identify broader pituitary dysfunction.

Imaging is essential to detect structural anomalies of the hypothalamic–pituitary region. MRI of the pituitary may reveal hypoplasia, ectopic posterior pituitary, or other midline defects. Genetic testing is increasingly used in congenital or familial cases to identify mutations affecting GH secretion or action.

Treatment Approaches

Recombinant Human Growth Hormone (rhGH)

Recombinant human GH is the mainstay of treatment, significantly improving height velocity and final height when initiated early.

IGF-1 Therapy

For GH insensitivity (e.g., Laron syndrome), GH replacement is ineffective; recombinant IGF-1 (mecasermin) is recommended.

Managing Other Pituitary Hormone Deficiencies

Central hypothyroidism: Thyroxine replacement ACTH deficiency: Glucocorticoids

Gonadotropin deficiency: Puberty induction protocols (e.g., gonadotropins)

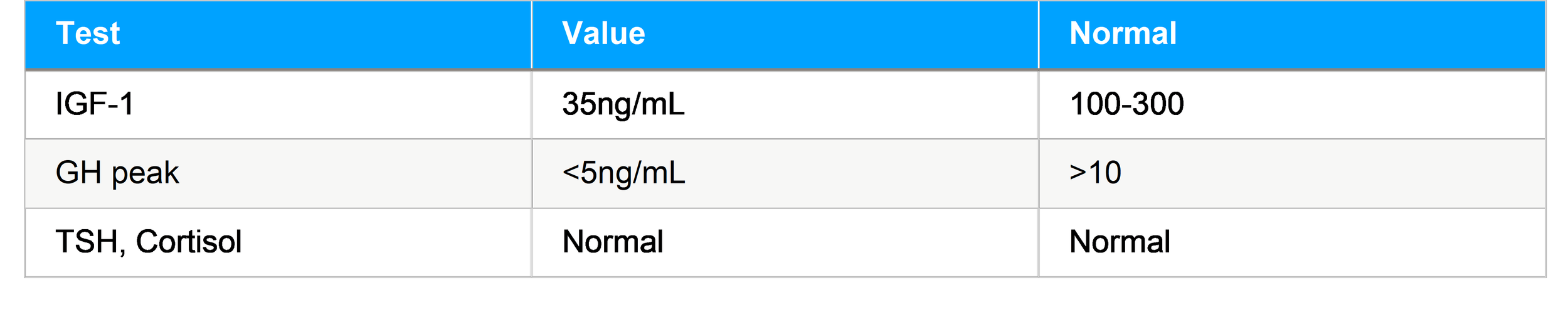

Growth Pattern Response (Bar Graph)

The bar graph displays the dramatic "catch-up growth" seen once treatment is initiated. Pre-Treatment: Children with pituitary dwarfism typically grow at a severely reduced rate, often averaging only 3.5 cm/year.

Year 1 of GH Therapy: Upon starting recombinant human Growth Hormone (rhGH) therapy, height velocity often peaks significantly, reaching an average of 8.9 cm/year.

Year 2 of GH Therapy: Growth velocity typically stabilizes as the child reaches a more normal percentile, averaging around 7.2 cm/year.

Treatment Outcomes

Height and Growth

GH therapy typically increases height SDS and accelerates annual growth velocity. Patients with complete GHD often show the most robust response.

Pubertal Development

Patients with MPHD require tailored hormone replacement to achieve normal puberty. Pubertal induction in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism shows progressive increases in sex steroid levels and physical maturation.

Pituitary Dwarfism and Quality of Life

Even after height improvement, patients may face challenges:

Self-image and psychosocial stress Need for prolonged daily injections

Ongoing monitoring for metabolic sequelae

Validated tools like QoL-AGHDA (Quality of Life Assessment of GH Deficiency in Adults) help assess the broader impact of GHD.

The cornerstone of managing pediatric pituitary dwarfism is recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) therapy, which significantly improves growth velocity and final adult height, especially when initiated early. Dosage is individualized based on weight, age, and growth response, with regular monitoring of height, growth velocity, bone age, and IGF‑1 levels to optimize therapy. In cases of multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies, additional hormone replacements such as thyroxine, glucocorticoids, or sex steroids are required. For GH insensitivity syndromes (e.g., Laron syndrome), rhGH is ineffective, and recombinant IGF‑1 therapy is used. Long-term follow- up ensures safety, adherence, and appropriate pubertal development.

1. Clinical Case Scenarios

Case 1: Isolated Growth Hormone Deficiency (IGHD)

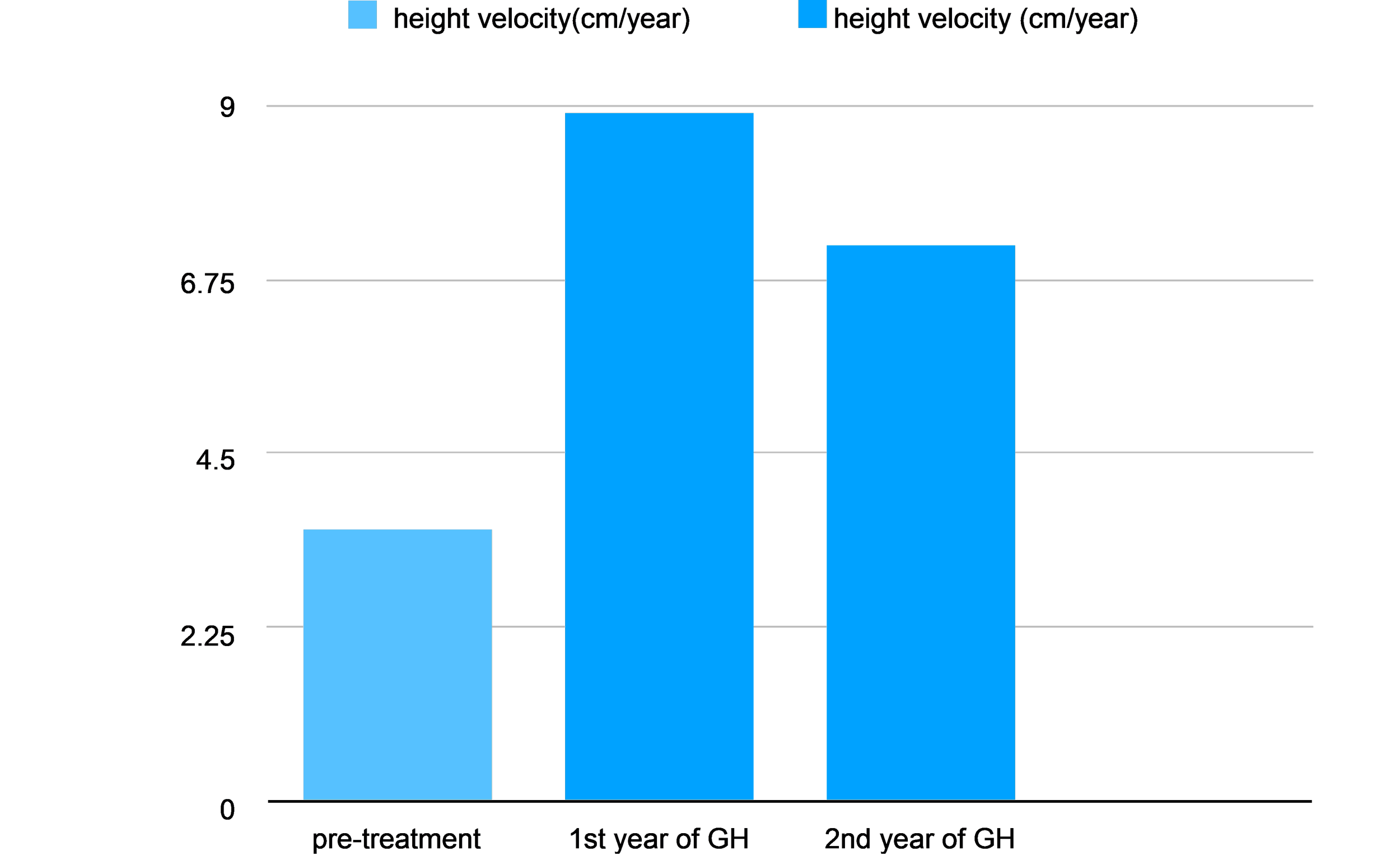

Presentation:A 7-year-old boy with height SDS −3.2, low growth velocity, delayed bone age. Laboratories:

Diagnosis: IGHD

Treatment: Initiated rhGH at 0.03 mg/kg/day Outcome: Height SDS improved to −2.0 in 18 months

Case 2: MPHD Presentation:

5-year-old girl with short stature, fatigue, and cold intolerance. Hormones:

GH peak: 3 ng/mL TSH: low

Cortisol: low

Management: Multihormone replacement + rhGH Result: Improved growth and metabolic stability

Laboratory Patterns and Differential Diagnosis

Laboratory evaluation plays a central role in distinguishing pituitary dwarfism from other causes of short stature in children. Since growth failure can arise from endocrine, genetic, nutritional, or systemic conditions, interpretation of hormonal patterns must always be integrated with clinical findings such as growth velocity, bone age, and physical examination.

In pituitary dwarfism due to isolated growth hormone deficiency (IGHD), basal growth hormone (GH) levels are usually low or undetectable, but because GH is secreted in pulses, random GH measurements are unreliable. Therefore, GH stimulation tests using agents such as insulin, clonidine, arginine, or glucagon are essential. A subnormal peak GH response (commonly <7–10 ng/mL, depending on assay and guidelines) supports the diagnosis. Serum insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and IGF-binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) are typically reduced, reflecting impaired GH action at the tissue level.

In multiple pituitary hormone deficiency (MPHD), laboratory abnormalities extend beyond the GH axis. In addition to low GH and IGF-1 levels, patients may show low free T4 with inappropriately normal or low TSH, reduced morning cortisol due to ACTH deficiency, and low gonadotropins for age. These findings suggest a broader pituitary or hypothalamic disorder and often warrant pituitary MRI for structural evaluation.

A key differential diagnosis is growth hormone insensitivity (Laron syndrome). In this condition, GH levels are normal or elevated, but IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels remain very low due to defective GH receptors. Unlike pituitary dwarfism, these patients do not respond to GH therapy and require recombinant IGF-1 treatment.

In contrast, children with constitutional delay of growth and puberty usually have normal GH stimulation test results, normal IGF-1 for bone age, and delayed bone maturation. Chronic systemic diseases, malnutrition, and hypothyroidism can also mimic pituitary dwarfism but are identified through abnormal inflammatory markers, nutritional indices, or thyroid function tests. Thus, careful analysis of laboratory patterns allows accurate differentiation of pituitary dwarfism from other causes of pediatric short stature, ensuring appropriate and timely treatment.

Summary and Clinical Pearls

Pituitary dwarfism in pediatrics, most commonly due to growth hormone deficiency, represents an important yet treatable cause of short stature in children. Early recognition is crucial, as timely intervention significantly improves growth outcomes, pubertal development, and overall quality of life. Children typically present with proportionate short stature, reduced growth velocity, and delayed bone age, while intelligence is usually normal. A detailed growth history and accurate serial height measurements are essential first steps in evaluation.

Laboratory assessment should focus on the growth hormone–IGF axis, recognizing that random GH levels are unreliable because of pulsatile secretion. Low IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels, followed by inadequate GH response on stimulation testing, support the diagnosis. Clinicians must also assess other pituitary hormones to identify multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies, which require broader hormonal replacement and careful long-term follow-up. Neuroimaging, particularly MRI of the hypothalamic–pituitary region, plays a key role in detecting structural abnormalities.

Recombinant human growth hormone therapy is the cornerstone of treatment and is most effective when initiated early, before severe growth failure or pubertal delay occurs. A robust increase in growth velocity during the first year of therapy is a strong predictor of favorable final height outcomes. Regular monitoring of growth response, bone age progression, and metabolic parameters is essential to optimize therapy and ensure safety.

Clinical pearls include remembering that not all short children have growth hormone deficiency, that poor response to GH should prompt reassessment of diagnosis and adherence, and that conditions such as GH insensitivity will not respond to GH therapy. Ultimately, a structured, evidence-based approach enables clinicians to distinguish pituitary dwarfism from other causes of short stature and deliver effective, individualized care.

Conclusion

Pituitary dwarfism in children is a significant but manageable endocrine disorder that primarily affects normal growth and physical development. Although it is a relatively rare cause of short stature, its impact on a child’s physical appearance, psychological well-being, and long-term health makes early diagnosis and proper treatment extremely important. With careful monitoring of growth patterns and appropriate hormonal evaluation, pituitary dwarfism can be accurately distinguished from other causes of delayed growth.

Advances in diagnostic techniques, including sensitive hormone assays and high-resolution imaging of the pituitary gland, have greatly improved early detection. Recombinant human growth hormone therapy has transformed the prognosis of affected children, allowing many to achieve near-normal adult height when treatment is started early and followed consistently. In cases where pituitary dwarfism is part of a broader hormonal deficiency, comprehensive replacement of other pituitary hormones further improves outcomes and overall health.

Equally important is long-term follow-up, which ensures optimal growth response, identifies potential side effects, and supports normal pubertal development. Attention to psychosocial aspects, such as self-esteem and social integration, is also essential in holistic care.

In conclusion, pituitary dwarfism is no longer a condition associated with poor outcomes. With early recognition, accurate diagnosis, and individualized therapy, most children can lead healthy, productive lives with normal physical and emotional development.

References

1. Endotext – Growth and Growth Disorders (Ergun-Longmire & Wajnrajch). Comprehensive text on growth physiology, GH deficiency diagnosis and treatment.

2. Endotext – Disorders of Growth Hormone in Childhood (Murray & Clayton). In- depth endocrine overview of GH & related disorders.

3. The Pituitary (Melmed S, editor). Authoritative endocrinology reference on pituitary disorders, including pediatric GH deficiency.

4. Pediatric Endocrinology (Feingold KR, et al.). Standard pediatric hormone reference covering growth disorders and therapies.

5. Grimberg A, DiVall SA, et al. Guidelines for GH/IGF-I treatment in children & adolescents. Horm Res Paediatr. 2016;86(6):361–397.

6. Alatzoglou KS, Webb EA, et al. Isolated growth hormone deficiency in childhood & adolescence: recent advances. Endocr Rev. 2014;35(3):376–432.

7. Growth Hormone Deficiency in Children – Pediatric Endocrine Society patient guide. Useful for clinical features & management basics.

8. Diagnosis of Growth Hormone Deficiency in Childhood review. Focus on testing limitations & auxologic evaluation.

9. Growth hormone treatment in children: review of safety and efficacy. Pediatric applications & outcomes summary.

10. Epidemiology of GHD in children & adolescents: systematic review (2014–2023). Highlights prevalence & diagnostic challenges.

11. Tilman R. Rohrer et al. Better growth outcomes in GH-deficient children treated younger than 2 years. Endocr Connect.

12. Soliman A et al. Growth response to GH treatment vs pretreatment IGF-1 levels. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2021.

13. Al-Zubaidi M et al. Effect of GH therapy on Iraqi children with GHD. Curr Pediatr Res. 2021.

14. Encyclopedia.com – Pituitary Dwarfism overview (books & periodical references).

15. Wikipedia – Laron Syndrome (GH insensitivity). Practical for differential diagnosis and phenotypes.