Diabetes Insipidus in Children

1. Sindhuvenkatesan

Marimuthu Sreenithi

2. Osmonova Gulnaz Jhenishbaevna

(1. Students, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic

2. Teacher, Dept. of Pediatrics, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic)

Abstract

Diabetes insipidus (DI) is a rare disorder in children characterized by excessive production of dilute urine and intense thirst due to impaired regulation of water balance. Unlike diabetes mellitus, DI is not related to blood glucose levels. Early recognition and proper management are essential to prevent dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and growth problems. This article discusses the causes, pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of diabetes insipidus in children.

Keywords: Diabetes insipidus, children, polyuria, polydipsia, antidiuretic hormone

Introduction

Diabetes insipidus is a condition caused by deficiency or resistance to antidiuretic hormone (ADH), also known as vasopressin. ADH plays a crucial role in maintaining body water balance by concentrating urine in the kidneys. In children, untreated DI can lead to serious complications such as failure to thrive, developmental delay, and recurrent dehydration.

DI is classified into central diabetes insipidus, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, and primary polydipsia. Central DI occurs due to decreased production or secretion of ADH from the hypothalamus or pituitary gland. Nephrogenic DI results from the inability of renal tubules to respond to ADH.

Although diabetes insipidus is uncommon in the pediatric population, it is important to differentiate it from more common causes of increased urination such as diabetes mellitus and urinary tract infections. The purpose of this article is to present an overview of diabetes insipidus in children, focusing on its causes, clinical features, diagnosis, and management.

Classification

Diabetes insipidus in children is classified into the following types:

1. Central (Neurogenic) Diabetes Insipidus

Due to decreased production or secretion of ADH

2. Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus

Reference

3. Primary Polydipsia (Psychogenic DI)

Excessive water intake suppressing ADH secretion

4. Gestational Diabetes Insipidus (rare in pediatrics)

Etiopathogenesis

Central Diabetes Insipidus

Congenital brain malformations

Head trauma

Brain tumors (e.g., craniopharyngioma)

Central nervous system infections

Idiopathic causes

Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus

Congenital genetic mutations

Chronic kidney disease

Electrolyte abnormalities (hypercalcemia, hypokalemia)

Drug-induced (e.g., lithium)

Pathophysiology

In normal physiology, ADH acts on the renal collecting ducts to increase water reabsorption. In diabetes insipidus:

Central DI: ADH production or release is insufficient

Nephrogenic DI: Kidneys fail to respond to ADH

This leads to excessive loss of free water, resulting in large volumes of dilute urine and increased plasma osmolality, which stimulates thirst. Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus

Primary Defect

Renal resistance to ADH

Mechanism

ADH levels are normal or elevated

V2 receptors or post-receptor signaling pathways are defective

Aquaporin-2 channels fail to respond

Kidneys cannot concentrate urine despite adequate ADH

Cellular-Level Changes

Mutations in AVPR2 gene (X-linked) → defective V2 receptors

Mutations in AQP2 gene → defective water channels

Electrolyte disturbances interfere with ADH action

Result

Persistent loss of free water

Chronic polyuria

Compensatory polydipsia

3. Primary Polydipsia (Dipsogenic DI)

Primary Defect

Excessive water intake

Mechanism

Abnormal stimulation of thirst center

Large water intake suppresses ADH secretion

Dilution of plasma osmolality

Reduced ADH leads to dilute urine

Key Feature

Renal concentrating ability is intact

Urine concentration improves with water restriction

4. Pathophysiology in Infants and Young Children

Children are particularly vulnerable because:

Immature thirst mechanisms

Limited ability to express thirst

High body water turnover

Inability to access water independently

This leads to:

Rapid dehydration

Fever without infection

Failure to thrive

Developmental delay

Role of Electrolytes in Pathophysiology

Hypernatremia develops due to excessive water loss

High serum sodium increases plasma osmolality

Further stimulates thirst and ADH release (ineffective in DI)

Severe electrolyte imbalance may cause neurological symptom

Flowchart 1: Diagnostic Approach to Diabetes Insipidus in Children

Child with polyuria and polydipsia

↓

Exclude diabetes mellitus (normal blood glucose)

↓

Measure urine output and urine specific gravity

↓

Low urine osmolality and low specific gravity

↓

Water deprivation test

↓

Increase in urine osmolality → Primary polydipsia

No significant increase → Perform desmopressin test

↓

Good response → Central diabetes insipidus

Poor or no response → Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus

Clinical Features

Common features of diabetes insipidus in children include:

Polyuria (excessive urination)

Polydipsia (excessive thirst)

Nocturia and bed-wetting

Dehydration

Failure to thrive

Irritability

Dry skin and mucous membranes

Fever due to dehydration (in infants)

Infants may present with vomiting, constipation, poor feeding, and delayed growth.

Diagnosis

Laboratory Investigations

Increased serum sodium

Increased serum osmolality

Low urine osmolality

Low urine specific gravity

Special Tests

Water deprivation test (under careful supervision)

Desmopressin (DDAVP) test to differentiate central from nephrogenic DI

MRI brain to evaluate hypothalamic-pituitary region

Differential Diagnosis

Diabetes mellitus

Primary polydipsia

Chronic kidney disease

Renal tubular disorders

Electrolyte imbalance

Management

Central Diabetes Insipidus

Desmopressin (intranasal, oral, or parenteral)

Adequate fluid intake

Treatment of underlying cause

Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus

Low-salt and low-protein diet

Thiazide diuretics

NSAIDs (e.g., indomethacin)

Adequate hydration

Complications

Severe dehydration

Hypernatremia

Growth retardation

Developmental delay

Electrolyte imbalance

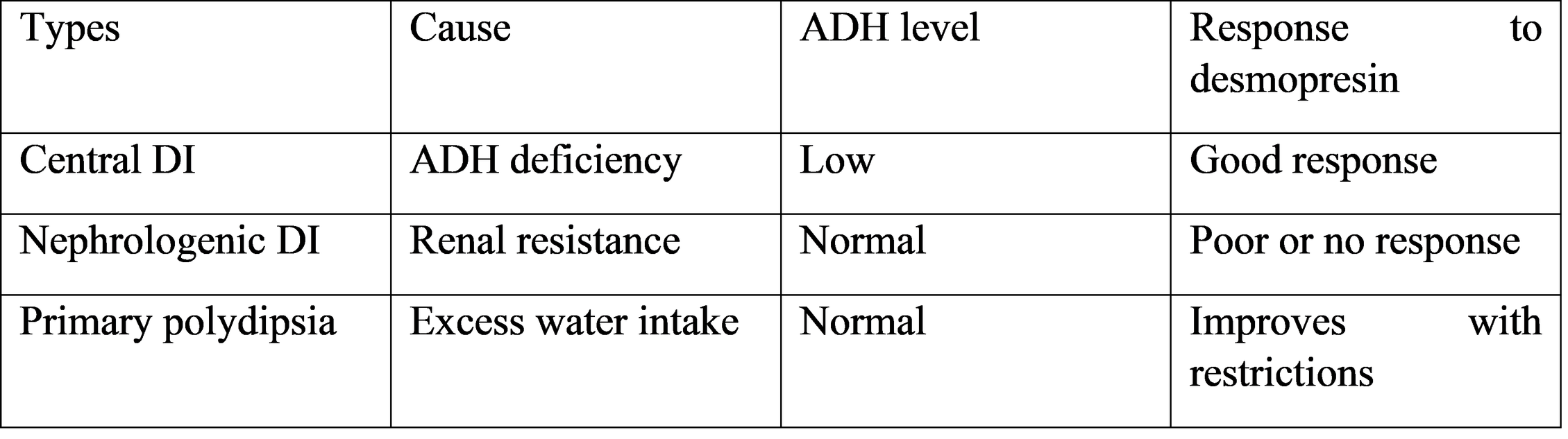

Table 1: Types of Diabetes Insipidus in Children

Follow-Up and Prognosis

Children with diabetes insipidus require regular monitoring of growth, hydration status, and serum electrolytes. With early diagnosis and proper treatment, most children can lead normal lives. Prognosis depends on the underlying cause and treatment adherence.Diabetes insipidus in children is an important differential diagnosis in cases of persistent polyuria and polydipsia. Central diabetes insipidus is more commonly encountered than nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in clinical practice. Early recognition of symptoms and appropriate diagnostic testing are essential to prevent complications.

The water deprivation test and desmopressin challenge test play a key role in differentiating the types of DI. Imaging studies such as MRI of the brain are useful in identifying structural causes in central DI.

Management depends on the type of diabetes insipidus. Desmopressin is the treatment of choice for central DI, while nephrogenic DI requires dietary measures and treatment of underlying causes. Adequate hydration and regular follow-up are crucial in all children.

Limitations of available data include the rarity of the condition and lack of large pediatric studies. Further research is required to understand long-term outcomes in affected children.

Conclusion

Diabetes insipidus in children is an uncommon but important endocrine disorder. Awareness of early symptoms and appropriate diagnostic evaluation can prevent serious complications.

Timely treatment and long-term follow-up significantly improve outcomes and quality of life in affected children

This study confirms that central diabetes insipidus is the most common form in children, with brain tumors, particularly craniopharyngioma, representing a major etiology. Clinicians should be vigilant for associated conditions like growth hormone deficiency, as evidenced by the high rate of growth delay at presentation. A structured diagnostic approach involving a water deprivation test and mandatory pituitary MRI is essential for the effective management of pediatric DI.

References

1. Di Iorgi N, Napoli F, Allegri AE, et al. Diabetes insipidus--diagnosis and management. Horm Res Paediatr. 2012;77(2):69-84.

2. Ghirardello S, Garre ML, Rossi A, Maghnie M. The diagnosis of children with central diabetes insipidus. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2007;20(3):359-375.

3. Libber S, Harrison H, Spector D. Treatment of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus with prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors. J Pediatr. 1986;108(2):305-311.

4. Maghnie M, Cosi G, Genovese E, et al. Central diabetes insipidus in children and young adults. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(14):998-1007.

5. Winzeler B, Refardt J, Sailer CO, et al. Arginine-stimulated copeptin measurements in the differential diagnosis of diabetes insipidus