Primary Adrenal Insufficiency in Children A Practical Diagnostic and Therapeutic Guide

1. Gulnaz Osmonova

2. Deepak Yadav

(Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Kyrgyzstan)

(Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Kyrgyzstan)

Abstract

Primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) is a rare but potentially life-threatening endocrine disorder characterized by inadequate production of glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids, and adrenal androgens. In the pediatric population, PAI encompasses a heterogeneous group of genetic and acquired conditions, with inherited disorders being predominant. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) remains the most common etiology; however, an expanding spectrum of non-CAH causes—including adrenal hypoplasia congenita, autoimmune adrenalitis, metabolic disorders, syndromic conditions, and defects in steroidogenesis—has been increasingly recognized due to advances in molecular diagnostics. The clinical presentation is often nonspecific, ranging from failure to thrive, recurrent hypoglycemia, and hyperpigmentation to life-threatening adrenal crisis, complicating early diagnosis. Consequently, a structured, personalized, and stepwise diagnostic approach incorporating biochemical evaluation, hormonal profiling, imaging, and genetic testing is essential. Prompt initiation of hormone replacement therapy is crucial to reduce morbidity and mortality; nevertheless, current treatment regimens are limited in their ability to mimic the physiological circadian rhythm of cortisol secretion, predisposing patients to suboptimal metabolic control, impaired growth, and reduced quality of life. Recent decades have witnessed significant progress in understanding the genetic basis, long-term outcomes, and novel therapeutic strategies for pediatric PAI, including modified-release glucocorticoids and emerging gene-based therapies. This review summarizes recent advances in the etiology, diagnosis, and management of childhood PAI and discusses future perspectives aimed at improving individualized care and clinical outcomes.

Keywords:

Primary adrenal insufficiency; pediatric adrenal disorders; congenital adrenal hyperplasia; adrenal crisis; glucocorticoid deficiency; mineralocorticoid deficiency; genetic adrenal diseases; steroidogenesis defects; adrenal hypoplasia congenita; autoimmune adrenalitis; hormonal replacement therapy; cortisol circadian rhythm; molecular diagnosis; pediatric endocrinology

Significance

Primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) in childhood is a rare but critical endocrine disorder with high morbidity and mortality if not promptly recognized and treated. Due to its heterogeneous etiology and often nonspecific clinical presentation, pediatric PAI remains underdiagnosed, leading to delayed intervention and increased risk of adrenal crisis. This review is significant as it consolidates current knowledge on both classical and newly identified genetic and acquired causes of PAI, emphasizing the importance of a structured and personalized diagnostic approach. By highlighting recent advances in molecular genetics and evolving therapeutic strategies, the article underscores how early and precise etiological diagnosis can improve clinical outcomes, optimize growth and development, and enhance long-term quality of life in affected children. Furthermore, the discussion on limitations of conventional hormone replacement therapy and emerging treatment modalities provides valuable insights for clinicians and researchers aiming to refine management strategies. Overall, this work contributes to improved awareness, early diagnosis, and evidence-based care of pediatric PAI, supporting better survival and long-term health outcomes.

Introduction

Adrenal insufficiency (AI) is a serious endocrine disorder in which the adrenal glands fail to produce adequate amounts of essential hormones, primarily glucocorticoids (GC). This deficiency is frequently accompanied by insufficient mineralocorticoid (MC) secretion and disturbances in adrenal androgen production, which may present as either deficiency or excess depending on the underlying cause. AI is broadly classified into primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI), caused by intrinsic adrenal gland failure, and secondary or tertiary adrenal insufficiency, which result from pituitary dysfunction or suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis due to prolonged exogenous steroid use, respectively.

The causes of PAI vary significantly with age. In adults, autoimmune adrenalitis and infectious diseases represent the leading etiologies. In contrast, childhood-onset PAI is predominantly due to inherited disorders, reflecting the crucial role of genetic defects affecting adrenal development, steroidogenesis, or adrenal responsiveness. Among these, congenital adrenal hyperplasia is the most frequent cause, although an increasing number of rare genetic and syndromic conditions have been identified in recent years.

Early recognition and timely initiation of treatment are essential to prevent adrenal crisis, a potentially fatal complication characterized by severe hypotension, hypoglycemia, electrolyte imbalance, and shock. However, diagnosing PAI in children remains particularly challenging. The initial symptoms—such as poor weight gain, fatigue, vomiting, recurrent infections, or skin hyperpigmentation—are often nonspecific and may be overlooked or attributed to more common pediatric illnesses. These challenges are further compounded by the lack of standardized diagnostic protocols, limited availability of pediatric reference ranges, and uncertainty regarding age-appropriate cortisol thresholds.

Despite advances in hormone replacement therapy, children with PAI continue to face an increased risk of morbidity and mortality. Long-term complications include impaired growth, delayed puberty, metabolic disturbances, and reduced quality of life, highlighting the limitations of current treatment strategies in replicating normal physiological hormone patterns.

Clinical Presentation of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency

The signs and symptoms of primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) are often vague and develop slowly over months or even years. Because of this gradual onset, diagnosis is frequently delayed. The clinical presentation varies depending on the child’s age, the severity of hormone deficiency, and the underlying cause of PAI.

Presentation in Newborns and Infants

In newborns, PAI usually presents with acute and severe symptoms. Common features include low blood sugar (hypoglycemia), electrolyte disturbances such as low sodium (hyponatremia) with or without high potassium (hyperkalemia), vomiting, poor feeding, weight loss, dehydration, and failure to thrive. Some infants may develop seizures, breathing pauses (apnea), prolonged jaundice, or lethargy. In severe cases, babies can present with hypovolemic shock or coma.

Because these symptoms closely resemble other emergency conditions like neonatal sepsis, PAI may be missed in critically ill infants. Disorders affecting adrenal androgen production can also lead to atypical genitalia at birth, especially in congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH).

Presentation in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults

In older children and adolescents, the onset of PAI is often subtle and progressive. Symptoms of glucocorticoid deficiency include persistent fatigue, weakness, lethargy, poor appetite, weight loss, dizziness on standing, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Laboratory abnormalities frequently include low sodium and low blood sugar, while high calcium levels are uncommon. Other findings may include anemia, mild eosinophilia, and lymphopenia.

One of the most characteristic signs of PAI is skin and mucosal hyperpigmentation. This occurs due to increased production of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which stimulates melanin production. Hyperpigmentation is most noticeable on the lips, inside the mouth, and on sun-exposed or pressure areas such as knuckles, elbows, and knees. However, this sign may be absent early in the disease and is more helpful in identifying chronic rather than acute PAI.

In adolescents, psychological symptoms such as poor appetite, depression, or behavioral changes may occur and can further delay diagnosis.

Signs of Mineralocorticoid Deficiency

Mineralocorticoid deficiency mainly affects salt and water balance. Clinical signs include poor growth, low blood pressure, dehydration, and, in severe cases, shock. Laboratory findings typically show low sodium levels, while potassium levels may be normal or mildly elevated at diagnosis, making hyperkalemia an inconsistent finding.

Effects of Androgen Imbalance

Conditions associated with excess adrenal androgens, such as CAH, may cause virilization at different ages. In contrast, reduced androgen production may result in delayed puberty, hypovirilization in males, or delayed adrenarche in both sexes.

Adrenal Crisis

A life-threatening adrenal crisis (AC) may be the first manifestation of previously undiagnosed PAI. If untreated, AC can rapidly progress to shock and death. Symptoms often include severe weakness, vomiting, abdominal pain, low blood pressure, altered consciousness, fever, and electrolyte disturbances such as hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, and hypoglycemia. These symptoms typically improve after prompt administration of intravenous glucocorticoids.

Adrenal crisis can also occur in patients with known PAI during periods of stress, such as infections or trauma, particularly if stress-dose steroids are not administered.

The reported incidence of AC in children with PAI ranges from approximately 3 to 11 episodes per 100 person-years. Younger children and those with frequent infections are at higher risk. Overall, adrenal crisis occurs more commonly in PAI than in secondary or tertiary adrenal insufficiency

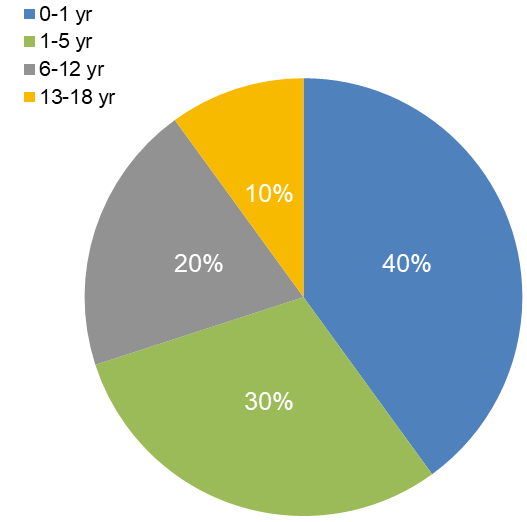

Incidence of crisis by age:

The pie chart shows the distribution of adrenal crisis (AC) incidence across different pediatric age groups. Infants (0–1 year) are at the highest risk, accounting for 40% of cases, likely due to their limited physiological reserves and difficulty in recognizing early symptoms. Young children (1–5 years) represent 30% of cases, while older children (6–12 years) and adolescents (13–18 years) account for 20% and 10%, respectively. This trend highlights that the risk of adrenal crisis decreases with age but remains clinically significant throughout childhood. Early recognition, prompt glucocorticoid replacement, and stress-dose education are essential to prevent life-threatening complications in all age groups.

Epidemiology and Etiology

Primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) can result from a variety of congenital and acquired conditions, and its prevalence varies with age. Overall, PAI is considered a rare disorder, with an estimated prevalence of approximately 100–140 cases per million people in the general population. However, the true incidence of PAI in children remains uncertain due to underdiagnosis and variability in reporting. Data from population-based studies are limited; for example, a Finnish study reported a cumulative incidence of about 10 cases per 100,000 children by 15 years of age.

In the pediatric population, inherited disorders account for the majority of PAI cases. Among these, congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is the most common and well-studied cause. CAH includes a group of enzymatic defects in cortisol biosynthesis, most frequently due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Because of newborn screening programs in many countries, CAH is often diagnosed early, reducing the risk of adrenal crisis and improving outcomes.

In contrast, non-CAH causes of PAI are highly heterogeneous and less well characterized. These include disorders of adrenal development (such as adrenal hypoplasia congenita), autoimmune adrenalitis, metabolic diseases, mitochondrial disorders, syndromic conditions, infections, and adrenal destruction due to hemorrhage or infiltration. Advances in genetic testing, particularly next-generation sequencing, have significantly improved the identification of rare genetic causes of PAI in children.

Although acquired causes of PAI are more common in adults, they may still occur in children, especially autoimmune conditions in adolescence or adrenal damage following severe illness. Continued research into the epidemiology and genetic basis of pediatric PAI is essential to improve early diagnosis, guide personalized management, and enhance long-term outcomes.

Genetic Causes of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency (PAI) in Children

Genetic disorders are the leading cause of primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) in the pediatric population. These conditions typically result from defects in adrenal development, steroid hormone biosynthesis, adrenal responsiveness to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), or adrenal cell survival. The age of onset, clinical severity, associated features, and hormonal profile vary widely depending on the underlying genetic defect. Advances in molecular genetics and next-generation sequencing have greatly expanded the spectrum of recognized genetic causes of childhood PAI, allowing for earlier diagnosis, targeted management, and improved genetic counseling.

The most common genetic cause of PAI in children is congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), a group of autosomal recessive disorders caused by enzymatic defects in cortisol synthesis. The majority of CAH cases are due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency (CYP21A2 mutations), which leads to cortisol deficiency with or without aldosterone deficiency and excess androgen production. Other rarer forms of CAH include 11β-hydroxylase, 17α-hydroxylase, and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiencies. These disorders often present in the neonatal period with adrenal crisis, atypical genitalia, or later with virilization, hypertension, or delayed puberty, depending on the specific enzyme defect.

Beyond CAH, several non-CAH genetic causes contribute to pediatric PAI. Adrenal hypoplasia congenita (AHC), commonly caused by mutations in the NR0B1 (DAX1) gene, leads to impaired adrenal development and typically presents in infancy or early childhood with salt-wasting adrenal crisis. This condition may also be associated with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism later in life. Mutations in SF1 (NR5A1) can similarly affect adrenal and gonadal development, resulting in a broad clinical spectrum.

Defects in adrenal responsiveness to ACTH represent another important category. Familial glucocorticoid deficiency (FGD) is caused by mutations in genes such as MC2R, MRAP, and STAR, leading to isolated cortisol deficiency with preserved mineralocorticoid function. Children with FGD often present with hypoglycemia, recurrent infections, and marked hyperpigmentation but normal electrolyte levels.

Additionally, PAI may occur as part of syndromic or metabolic disorders, including triple A (Allgrove) syndrome, mitochondrial diseases, peroxisomal disorders, and disorders of cholesterol metabolism. These conditions often present with extra-adrenal features such as neurological impairment, alacrima, achalasia, or failure to thrive, which can provide important diagnostic clues.

Early identification of genetic causes of PAI is crucial, as it allows for individualized treatment, anticipatory management of associated conditions, family screening, and prenatal counseling.

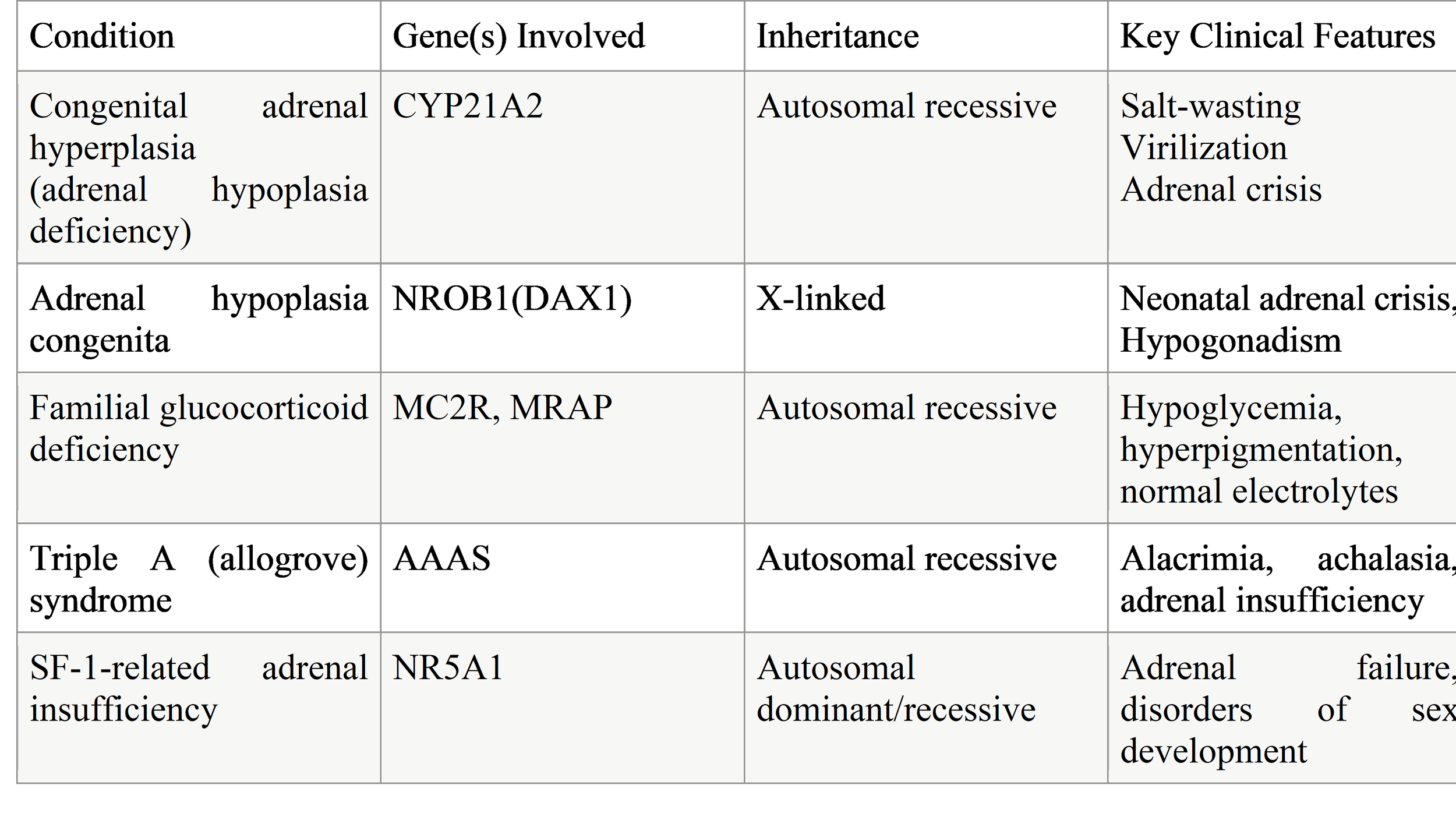

Table 1. Common Genetic Causes of PAI in Children

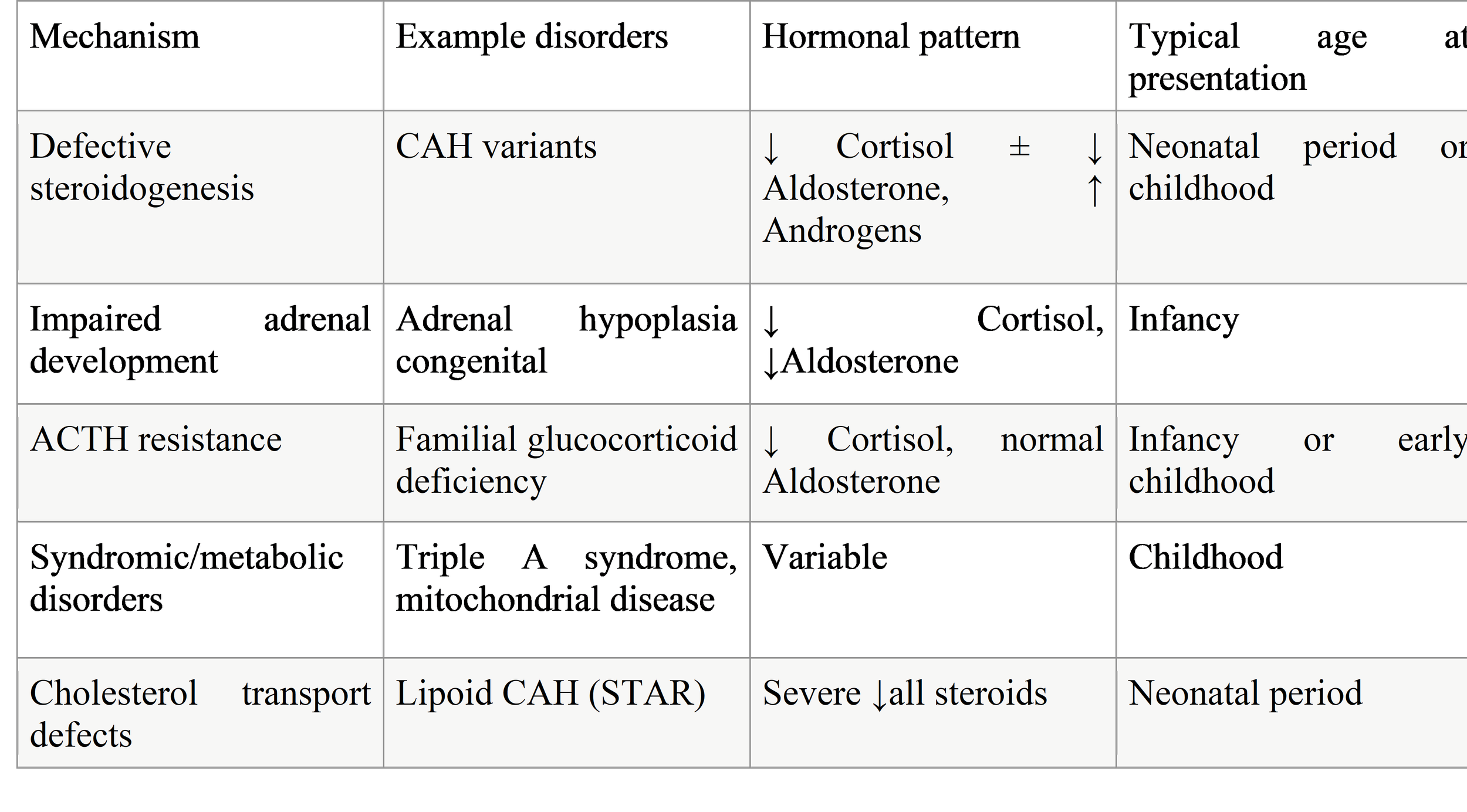

Table 2. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Genetic PAI

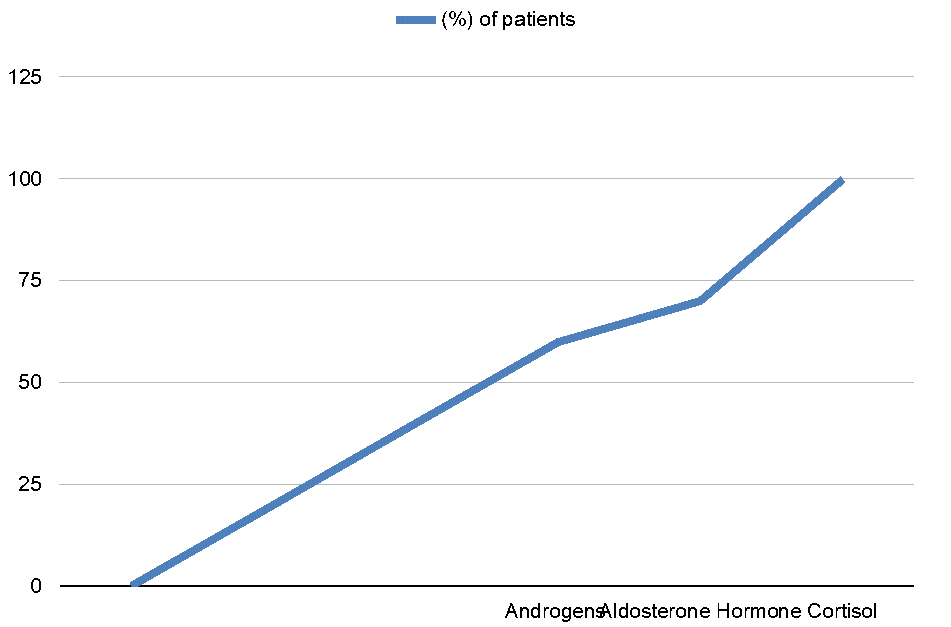

Hormone Deficiency Patterns in Pediatrics PAI:

The line chart illustrates the prevalence of hormone deficiencies in children with primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI). As shown, cortisol deficiency affects 100% of patients, reflecting its central role in the pathophysiology of PAI and highlighting why glucocorticoid replacement is universally required. Aldosterone deficiency occurs in approximately 70% of cases, primarily in salt-wasting forms of PAI such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) or adrenal hypoplasia congenita. This deficiency contributes to electrolyte imbalances, including hyponatremia and hyperkalemia, and necessitates mineralocorticoid supplementation in affected children. Androgen deficiency or excess is observed in around 60% of patients, mostly depending on the underlying etiology. For example, children with classic CAH often present with androgen excess, while others with adrenal hypoplasia may have androgen deficiency, affecting sexual development and pubertal progression. The chart emphasizes that cortisol replacement is mandatory, while aldosterone and androgen management must be individualized based on the specific hormonal profile and clinical presentation of each child.

Impaired Steroidogenesis

Impaired steroidogenesis is the most common mechanism leading to primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) in children. It results from genetic defects affecting enzymes or proteins involved in the synthesis of adrenal steroid hormones, particularly cortisol, aldosterone, and adrenal androgens. When cortisol production is reduced, the pituitary gland increases adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion, which can lead to adrenal hyperplasia and, in some conditions, excess androgen production.

The best-known disorders in this category are forms of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). The most frequent type is 21-hydroxylase deficiency, caused by mutations in the CYP21A2 gene. This defect leads to impaired cortisol synthesis and, in severe forms, aldosterone deficiency, resulting in salt-wasting, dehydration, hypotension, and adrenal crisis in infancy. Accumulation of steroid precursors diverts hormone production toward androgen synthesis, causing virilization in females and early puberty in males.

Other enzyme defects include 11β-hydroxylase deficiency, which is associated with hypertension due to excess mineralocorticoid precursors, and 17α-hydroxylase deficiency, characterized by cortisol and sex steroid deficiency with hypertension and delayed puberty. Rare disorders such as 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency and lipoid CAH (STAR mutations) cause severe impairment of all steroid hormones and often present in the neonatal period.

The clinical severity depends on the specific enzyme affected and the degree of residual activity. Early diagnosis through newborn screening, hormonal evaluation, and genetic testing is critical to prevent adrenal crisis and ensure appropriate hormone replacement and long-term follow-up.

Defects in Metabolic Pathways

Defects in metabolic pathways that support adrenal function represent an important but less common cause of PAI in children. These disorders do not directly involve steroidogenic enzymes but instead impair cellular processes necessary for adrenal hormone production, adrenal cell survival, or energy metabolism.

Several mitochondrial disorders can lead to PAI because steroidogenesis is a highly energy-dependent process that relies on normal mitochondrial function. Mutations affecting mitochondrial DNA or nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial proteins may result in combined adrenal insufficiency, neurological impairment, myopathy, and growth failure. In these patients, adrenal insufficiency may be one of the earliest signs or may develop as part of a progressive multisystem disease.

Peroxisomal disorders, such as X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), are another important cause. In ALD, mutations in the ABCD1 gene lead to accumulation of very-long-chain fatty acids, which damage adrenal cortical cells and white matter in the brain. Adrenal insufficiency may precede neurological symptoms by years, highlighting the importance of early recognition and biochemical screening.

Defects in cholesterol metabolism and transport can also impair steroid hormone synthesis. Cholesterol is the essential substrate for steroidogenesis, and disruptions in its availability can lead to adrenal failure. These conditions often present with failure to thrive, liver disease, developmental delay, and adrenal insufficiency.

Because metabolic disorders often involve multiple organ systems, the presence of neurological, hepatic, or muscular symptoms alongside adrenal insufficiency should raise suspicion of an underlying metabolic cause. Early diagnosis allows timely initiation of hormone replacement and appropriate multidisciplinary care.

Abnormal Gland Development

Abnormal development of the adrenal glands is another important genetic mechanism leading to PAI in children. These conditions are typically caused by mutations in genes that regulate adrenal organ formation, differentiation, and maintenance during fetal development.

Adrenal hypoplasia congenita (AHC) is the most well-recognized disorder in this group. It is most commonly caused by mutations in the NR0B1 (DAX1) gene and is inherited in an X-linked manner. Affected infants usually present in early life with salt-wasting adrenal crisis, hypoglycemia, vomiting, dehydration, and failure to thrive. Over time, patients may also develop hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, leading to delayed or absent puberty.

Mutations in NR5A1 (SF-1) can also disrupt adrenal and gonadal development. These patients show a wide range of clinical presentations, from severe neonatal adrenal failure to milder, later-onset disease. Disorders of sex development are frequently associated and can provide an important diagnostic clue.

In these conditions, the adrenal glands are structurally small or underdeveloped and unable to produce sufficient steroid hormones. Unlike CAH, there is no excess androgen production, and hyperpigmentation may be prominent due to high ACTH levels.

Early recognition of developmental adrenal disorders is crucial, as prompt hormone replacement therapy is lifesaving. Genetic diagnosis also allows family screening and counseling, particularly in X-linked conditions.

Progressive Destruction of the Adrenal Gland

Progressive destruction of the adrenal cortex is a key mechanism of PAI, particularly in older children and adolescents. In this group of disorders, adrenal function may be normal at birth but gradually declines over time as adrenal tissue is damaged.

Autoimmune adrenalitis is the most common cause of adrenal destruction in adolescents. It may occur as an isolated condition or as part of autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes (APS), such as APS type 1 or type 2. Autoantibodies against adrenal enzymes lead to gradual loss of adrenal cortical cells, resulting in cortisol and aldosterone deficiency. Symptoms often develop slowly and may include fatigue, weight loss, hyperpigmentation, and recurrent illness.

Infectious causes, although rare in children, can also destroy adrenal tissue. Tuberculosis, fungal infections, and viral infections may cause adrenal damage, especially in immunocompromised patients.

Hemorrhage, infiltration, or tumors affecting the adrenal glands can lead to irreversible adrenal failure. In neonates, adrenal hemorrhage may occur following birth trauma or severe illness, while in older children malignancy or metastatic disease may be responsible.

In progressive adrenal destruction, adrenal crisis may be the first presentation, particularly during stress or infection. Lifelong hormone replacement and careful monitoring are required, as adrenal function does not recover once significant tissue damage has occurred.

Acquired Causes of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency in Children

Although most cases of primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) in children are genetic, acquired forms do occur and should be considered, especially in older children and adolescents. Acquired PAI results from damage to previously normal adrenal glands, leading to reduced cortisol and/or aldosterone production. The onset can be rapid or gradual, depending on the cause, and clinical features are similar to those of genetic PAI.

1. Autoimmune Adrenalitis

Autoimmune adrenalitis is the most common acquired cause of PAI in adolescents. It occurs when the immune system produces antibodies against adrenal cortical cells or steroidogenic enzymes, gradually destroying adrenal tissue. Children may present with fatigue, hyperpigmentation, salt craving, hypotension, and poor growth. Autoimmune adrenalitis can occur in isolation or as part of Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndromes (APS):

APS Type 1 typically presents in childhood and is characterized by adrenal insufficiency, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, and hypoparathyroidism.

APS Type 2 usually appears in adolescence and may include adrenal insufficiency along with autoimmune thyroid disease or type 1 diabetes.

Detection of adrenal autoantibodies can support the diagnosis, although clinical suspicion remains critical.

2. Infectious Causes

Infections can directly damage the adrenal glands, although this is uncommon in children. Examples include:

Bacterial infections, such as Neisseria meningitidis, can cause adrenal hemorrhage (Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome), presenting acutely with shock, fever, and widespread purpura.

Viral infections, including cytomegalovirus, can occasionally affect adrenal function, particularly in immunocompromised children.

Tuberculosis and fungal infections may involve the adrenal glands in endemic areas or immunodeficient patients, often leading to chronic adrenal insufficiency.

Prompt recognition is critical, as adrenal crisis can develop rapidly in these conditions.

3. Hemorrhage and Trauma

Adrenal hemorrhage can occur in neonates due to birth trauma, hypoxia, or severe stress. Large hemorrhages may destroy sufficient adrenal tissue to cause PAI, sometimes presenting days to weeks after birth with hypotension, hypoglycemia, or jaundice. In older children, adrenal trauma following severe abdominal injury may rarely result in adrenal insufficiency.

4. Infiltrative and Neoplastic Causes

Rarely, infiltrative disorders or tumors can damage adrenal tissue, leading to PAI. Examples include:

Metastatic disease (from leukemia, lymphoma)

Storage disorders (e.g., Wolman disease, adrenoleukodystrophy)

Granulomatous infiltration (sarcoidosis or Langerhans cell histiocytosis)

These conditions often present with systemic symptoms such as growth failure, hepatosplenomegaly, or neurological deficits in addition to adrenal insufficiency.

5. Drug-Induced or Toxin-Related PAI

Certain medications or toxins can cause acquired PAI, usually by direct adrenal toxicity or by suppressing adrenal function during stress. Examples include:

Mitotane (used in adrenal tumors)

Ketoconazole or etomidate (inhibits steroidogenesis)

Abrupt withdrawal of long-term exogenous steroids can unmask adrenal insufficiency if the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis is suppressed

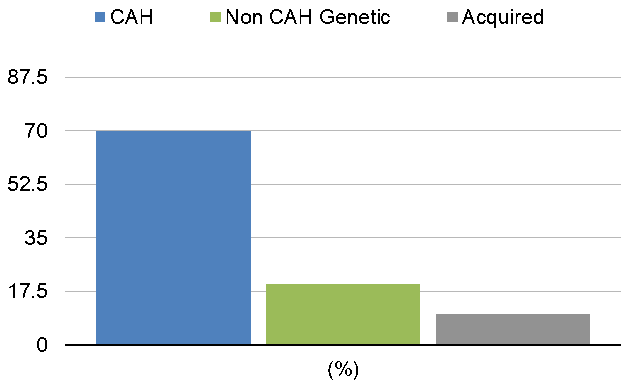

The bar graph illustrates the relative frequency of different causes of pediatric primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI). Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is the most common cause, accounting for approximately 70% of cases, reflecting the predominance of inherited enzyme defects such as 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Non-CAH genetic disorders contribute to around 20% of cases, including adrenal hypoplasia congenita, familial glucocorticoid deficiency, and other rare monogenic forms. Acquired causes, such as autoimmune adrenalitis, infections, or adrenal hemorrhage, are less frequent, representing roughly 10% of cases. The graph emphasizes the importance of considering genetic etiologies in children, guiding diagnostic evaluation and personalized management strategies for hormone replacement and long-term follow-up.

Diagnostic Approach to a Child with Suspected PAI

Diagnosing primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) in children requires a combination of clinical suspicion, biochemical testing, and identification of the underlying cause. Early recognition is essential to prevent adrenal crisis and optimize long-term outcomes.

1. Biochemical Confirmation of PAI

Biochemical testing aims to confirm the presence of adrenal hormone deficiency. Key steps include:

a) Baseline Hormonal Assessment

Serum cortisol: Morning cortisol measurement is the first step. Low cortisol (<5 µg/dL or <140 nmol/L in most pediatric reference ranges) raises suspicion of adrenal insufficiency.

Plasma ACTH: In PAI, ACTH is typically elevated due to lack of negative feedback on the pituitary. Very high levels (>2–3 times normal) support primary adrenal failure.

Electrolytes: Hyponatremia and hyperkalemia are classic indicators of aldosterone deficiency. Mild hyperkalemia may be absent in some cases.

Blood glucose: Hypoglycemia is common in infants and young children with cortisol deficiency.

b) Dynamic Testing

ACTH stimulation (Synacthen) test: This is the gold standard for confirming PAI. A synthetic ACTH analogue is administered, and cortisol response is measured. Blunted or absent cortisol rise confirms adrenal insufficiency.

Renin and aldosterone levels: Elevated plasma renin activity with low aldosterone indicates mineralocorticoid deficiency, typical of PAI.

2. Identification of the Underlying Etiology

Once adrenal insufficiency is confirmed, identifying the cause is essential for targeted treatment and genetic counseling.

a) Genetic Causes

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH): Suspected in neonates or children with atypical genitalia, salt-wasting crisis, or family history. Hormonal profiles (17-hydroxyprogesterone, androstenedione, and steroid precursors) and genetic testing confirm the diagnosis.

Adrenal hypoplasia congenita or SF-1 related defects: Consider in boys with early-onset PAI and later hypogonadism. Genetic testing is recommended.

Familial glucocorticoid deficiency: Marked cortisol deficiency with normal electrolytes; genetic testing for MC2R, MRAP, or STAR mutations can confirm the diagnosis.

b) Acquired Causes

Autoimmune adrenalitis: Check for adrenal autoantibodies (anti-21-hydroxylase). Assess for other autoimmune diseases (thyroid, type 1 diabetes, celiac).

Infections: History, imaging, and microbiological tests may reveal tuberculosis, fungal, or viral infections affecting the adrenal glands.

Hemorrhage, trauma, or infiltration: Imaging (ultrasound, CT, or MRI) can detect adrenal hemorrhage, tumors, or infiltrative disorders.

c) Syndromic or Metabolic Causes

Consider if adrenal insufficiency is accompanied by neurological deficits, developmental delay, or liver disease. Tests may include very-long-chain fatty acids for X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy, mitochondrial function tests, or peroxisomal disorder screening.

Diagnostic algorithm for suspected pediatric PAI

Clinical suspicion

↓

Evaluate for fatigue, hyperpigmentation, salt-wasting, hypoglycemia.

↓

Baseline labs

↓

Morning cortisol, ACTH, electrolytes, glucose.

Confirmatory test → ACTH stimulation test.

Identify etiology → Hormonal profile, autoantibodies, genetic testing, imaging.

Initiate treatment → Stress-dose steroids if adrenal crisis is imminent.

Treatment and Management of Pediatric PAI

Management of primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) in children aims to replace deficient hormones, prevent adrenal crisis, manage acute episodes, and optimize growth and development. Early recognition and individualized therapy are crucial to reduce morbidity and mortality.

1. Glucocorticoid Replacement

Glucocorticoid (GC) therapy is the cornerstone of treatment, as cortisol deficiency is life-threatening.

Hydrocortisone is the preferred glucocorticoid in children due to its short half-life and physiologic profile.

Dosing: Typically 8–12 mg/m²/day, divided into 2–3 doses to mimic the natural diurnal rhythm (higher in the morning, lower in the evening).

Monitoring: Clinical response (growth, energy, weight), blood pressure, and signs of over- or under-replacement. Excess glucocorticoid may impair growth, bone density, and metabolic health; insufficient dosing increases risk of adrenal crisis.

Alternative glucocorticoids: Prednisolone or dexamethasone may be used in selected older children or adolescents but are generally less preferred due to longer half-lives and higher potency.

2. Mineralocorticoid Replacement

Mineralocorticoid (MC) therapy is required when aldosterone deficiency is present, typically in salt-wasting forms of PAI.

Fludrocortisone is the standard agent.

Dosing: 0.05–0.2 mg/day, adjusted based on blood pressure, serum sodium and potassium levels, and plasma renin activity.

Monitoring: Growth, blood pressure, electrolytes, and renin levels help ensure appropriate replacement.

Sodium supplementation may be necessary in neonates or infants with significant salt-wasting.

3. Stress-Dose Steroids and Adrenal Crisis Management

Children with PAI are unable to mount an adequate cortisol response to stress. Stress dosing during illness, surgery, or trauma is essential.

Minor illness: Double the usual oral hydrocortisone dose for 1–3 days.

Moderate/severe illness or vomiting: Administer parenteral hydrocortisone (50–100 mg/m²/day IV divided every 6–8 hours) and provide fluid and electrolyte replacement.

Adrenal crisis: Rapid recognition is critical. Immediate IV hydrocortisone, aggressive fluid resuscitation with isotonic saline, correction of hypoglycemia, and monitoring for hypotension and electrolyte disturbances are life-saving.

Education of families and caregivers is vital to ensure prompt stress-dose administration during illness.

4. Androgen Replacement (If Needed)

In some forms of PAI with adrenal androgen deficiency (e.g., adrenal hypoplasia congenita), DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone) supplementation may be considered in older children or adolescents to improve energy, mood, and pubertal development.

Careful monitoring is required to avoid premature virilization.

5. Long-Term Monitoring and Management

Chronic management includes:

Growth and development: Regular assessment of height, weight, and pubertal progression.

Metabolic health: Monitor for obesity, hypertension, glucose intolerance, or osteoporosis due to prolonged steroid therapy.

Education: Patients and caregivers must be trained in emergency steroid use, identification of adrenal crisis, and wearing medical alert identification.

Genetic counseling: Recommended for families with inherited forms of PAI.

6. Emerging Therapies

Recent advances aim to improve physiologic hormone replacement:

Modified-release hydrocortisone to better replicate circadian cortisol rhythm.

Continuous subcutaneous hydrocortisone infusion (CSHI) for children with poor control or frequent adrenal crises.

Gene therapy and molecular therapies are under investigation for rare monogenic forms of PAI.

Outcome

Children and adults with primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) face several long-term health challenges, and their outcomes depend on the underlying cause, quality of hormone replacement, and disease control.

In adults with PAI, studies show a two-fold higher risk of death compared to the general population. Patients with 21-hydroxylase deficiency (21OHD), the most common form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), are particularly prone to long-term complications. These include cardiometabolic problems (like obesity, high blood pressure, and insulin resistance), reduced fertility, lower bone density, mental health issues, and a decreased quality of life (QoL).

Evidence suggests that many of these problems actually start in childhood and adolescence. In children with 21OHD, the main challenges are related to excess androgens, which can cause virilization, early puberty, rapid skeletal growth, and eventually short adult stature. Studies have also reported that these children are at higher risk of early-onset obesity, metabolic syndrome, and bone health problems. Some research suggests possible effects on brain development and working memory, but the data are still unclear. Both under-treatment and over-treatment of hormones, as well as poor hormonal control, can contribute to these adverse outcomes.

For children with non-CAH forms of PAI, data are limited due to the rarity and diversity of these disorders. However, impaired linear growth remains a common concern. Some studies show that children with non-CAH PAI can reach normal adult height, but often fall short of their parental height expectations.

Recent studies during the COVID-19 pandemic indicate that children with PAI do not seem to have a higher risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 or developing severe disease, suggesting that their basic immune defenses remain largely intact. However, further research is needed to fully understand immune function in these patients.

Overall, the key factors influencing outcomes in pediatric PAI are early diagnosis, adequate hormone replacement, careful monitoring, and management of growth, metabolic health, and quality of life.

New Therapeutic Approaches and Future Directions

Current treatments for pediatric PAI, especially 21-hydroxylase deficiency (21OHD), have limitations, including difficulty mimicking the natural cortisol rhythm and controlling excess androgens. Several new strategies are being developed to improve outcomes and reduce total glucocorticoid doses.

For infants and young children, precise dosing has been a challenge with crushed hydrocortisone tablets. In 2018, immediate-release hydrocortisone granules (Infacort) were approved in doses of 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 mg, allowing accurate dosing and better disease control in early childhood.

Modified-release formulations aim to mimic natural cortisol patterns. Chronocort, recently licensed in Europe for children over 12, provides delayed and sustained hydrocortisone release to reduce ACTH surges and androgen excess. Plenadren, approved for adults, is less effective for 21OHD.

Adjunct therapies are also emerging:

Crinecerfont (Crenessity) is approved in the U.S. for children over 4 years with classic CAH to reduce androgens while lowering glucocorticoid doses.

Trials are underway for MC2R inhibitors (Atumelnant) and ACTH antibodies, which aim to reduce glucocorticoid requirements and improve quality of life.

Continuous subcutaneous hydrocortisone infusion (CSHI) via a pump has been studied in adults and children as a way to deliver physiologic cortisol replacement, though it is costly, invasive, and may cause skin reactions.

Gene therapy and adrenal cell transplantation are experimental approaches to restore adrenal function. A phase 1 gene therapy trial for adults with 21OHD has been conducted, but further development is currently paused.

Overall, these emerging therapies aim to improve hormone control, growth, quality of life, and reduce the risks associated with long-term glucocorticoid therapy, particularly in children with CAH.

Conclusions

Primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) is a serious, potentially life-threatening condition in children. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are crucial to prevent adrenal crises and minimize long-term complications. Despite progress in both diagnosis and therapy, managing PAI remains challenging, as treatment must be carefully individualized to mimic the natural circadian rhythm of cortisol and maintain an appropriate balance of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement. Emerging therapies—including modified-release hydrocortisone, adjunct medications, and novel strategies such as gene therapy—offer promising avenues for improved care, but further research is needed to confirm their safety and efficacy. Well-designed clinical trials and the identification of reliable biomarkers are urgently required to optimize treatment, support normal growth and metabolic health, and enhance the overall quality of life for children living with PAI.

References

1.Kilberg MJ, Vogiatzi MG. Adrenal Insufficiency in Children. In: Feingold KR, Adler RA, Ahmed SF, et al., eds. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2024.

2.Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016.

3.Ergun‑Longmire B, Rowland D, Dewey J, Vining‑Maravolo P. A narrative review: an update on PAI in pediatric population. Pediatr Med (Tokyo). 2025.

4.Current and Novel Treatment Strategies in Children with CAH. Horm Res Paediatr. 2023;96(6):560–575.

5.Çamtosun E, Dündar İ, Akıncı A, et al. Pediatric Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: A 21‑year Single Center Experience. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2021;13(1):88–99.

6.Primary Adrenal Insufficiency in Childhood: Data From a Large Nationwide Cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021.

7.Liu Z, Chen X, Gao K, et al. The etiology and clinical features of non‑CAH PAI in children. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:961268.

8.Atar M, Akın L. The Causes and Diagnosis of Non‑congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia PAI in Children. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2025;17(1):66–71.

9.Malik A, Hines EQ. Pediatric Emergency Management of Adrenal Insufficiency and Adrenal Crisis. EMRA; 2022.

10.Autoimmune Primary Adrenal Insufficiency in Children. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2022.

11.Minaeian N, Fraga NR, Kim MS. Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH). Pediatr Rev. 2024;45(2):74–84.

12.Genetic aetiology of primary adrenal insufficiency in Chinese children. BMC Med Genomics. 2021;14:172.

13.GNAS mutation is an unusual cause of PAI: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22:472.

14.National Adrenal Diseases Foundation: Medical Publications on adrenal diseases. nadf.us/medical‑publications.html.