Parathyroid Dysfunction in Childhood: Hypoparathyroid Tetany and Hyperparathyroidism

1. Gulnaz Osmonova

2. MD Imran

(Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Kyrgyz Republic)

(Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Kyrgyz Republic)

Abstract

Parathyroid disorders in childhood are uncommon but clinically significant endocrine conditions that primarily affect calcium and phosphate homeostasis. Dysfunction of the parathyroid glands may present as hypoparathyroidism, leading to hypocalcemia and tetany, or as hyperparathyroidism, resulting in hypercalcemia with multisystem involvement. In children, these disorders may be congenital, genetic, autoimmune, or acquired, and their clinical manifestations differ markedly from those in adults. Early recognition is essential to prevent life-threatening complications such as seizures, cardiac arrhythmias, nephrocalcinosis, and skeletal deformities. This review provides an overview of the epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnosis, and management of hypoparathyroid tetany and hyperparathyroidism in the pediatric population, with emphasis on practical clinical and examination-oriented aspects.

Keywords: Parathyroid hormone, Hypocalcemia, Tetany, Hypercalcemia, Pediatric endocrinology, Hypoparathyroidism, Hyperparathyroidism

Introduction

The parathyroid glands play a critical role in maintaining calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D balance through secretion of parathyroid.

Parathyroid disorders in childhood disrupt calcium homeostasis, with hypoparathyroidism causing insufficient PTH secretion and hyperparathyroidism involving excess PTH. These conditions are uncommon but can lead to severe complications like tetany, nephrocalcinosis, or renal failure if unmanaged. Timely diagnosis via serum calcium, PTH, and genetic testing is crucial, particularly in syndromic cases prevalent in pediatric populations.

The parathyroid glands, four tiny pea-sized structures nestled behind the thyroid, serve as the body’s master regulators of calcium homeostasis. In children, the precise management of serum calcium is not merely a matter of metabolic stability, but a fundamental requirement for skeletal growth, neurological development, and muscular function.

When the delicate hormonal balance of the parathyroid is disrupted—either through a deficiency or an excess of Parathyroid Hormone (PTH)—the clinical consequences in pediatric patients can be profound and, at times, acute.

The Spectrum of Dysfunction

This article explores the two clinical extremes of parathyroid pathology in childhood:

Hypoparathyroidism and Tetany: Often arising from congenital anomalies (such as DiGeorge syndrome) or autoimmune destruction, a lack of PTH leads to profound hypocalcemia. The most striking manifestation is tetany—a state of neuromuscular irritability characterized by involuntary muscle spasms, paresthesia, and, in severe cases, laryngospasm or seizures.

Hyperparathyroidism: Conversely, the overproduction of PTH—whether primary (due to a rare adenoma) or secondary (often resulting from Vitamin D deficiency or chronic kidney disease)—leads to hypercalcemia. In children, this can manifest as "bones, stones, and abdominal groans," potentially causing permanent damage to developing kidneys and bone density.

Global Epidemiological Patterns Incidence and Prevalence.

Hypoparathyroidism affects children through congenital or acquired forms, with postsurgical cases common after thyroidectomy; genetic etiologies like APECED present in early childhood. Hyperparathyroidism is rare, occurring in <1% of pediatric endocrine disorders, often linked to MEN syndromes or adenomas.Median onset for hypoparathyroid symptoms is around 17 months, with seizures in most cases.

Incidence Comparison Chart

The following grouped bar chart compares approximate incidence/prevalence rates per 100,000 person-years for hypoparathyroidism (~30 general, rarer in pediatrics at ~2.5) versus hyperparathyroidism (~100 general/adult, ~3.5 pediatric). Hypoparathyroidism data reflects U.S. estimates; hyperparathyroidism highlights pediatric rarity.

The statistics and visual data below summarize the geographic and age-related variations in childhood parathyroid dysfunction, specifically highlighting the differences between hypoparathyroidism (often associated with APECED) and hyperparathyroidism.

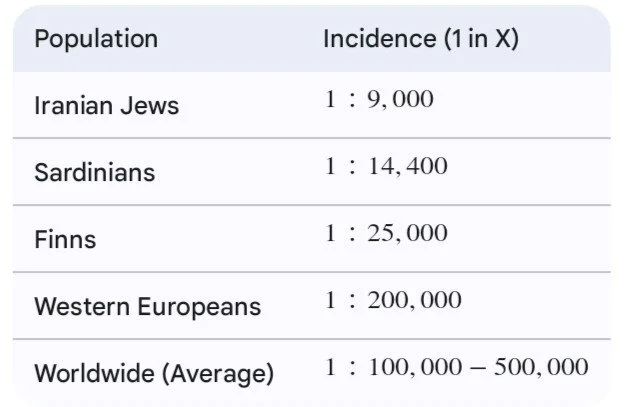

1. Geographic Variations: APECED Incidence

Autoimmune Polyendocrinopathy-Candidiasis-Ectodermal Dystrophy (APECED), also known as APS-1, is a primary cause of childhood hypoparathyroidism. Its incidence varies drastically across ethnic groups due to founder effects.

2. Age Variations in Onset

The timing of parathyroid dysfunction symptoms differs significantly based on the specific disorder:

Hypoparathyroid Tetany: Frequently peaks in infancy and toddlerhood. In many cases, it presents as neonatal hypocalcemia or later in the first decade of life. A common first sign in children is seizures (21.8\%) or muscle spasms (32.7\%).

Hyperparathyroidism: A rare condition in children (incidence of 2–5 per 100,000), it typically peaks post-puberty, with a median diagnosis age of 15 to 18 years.

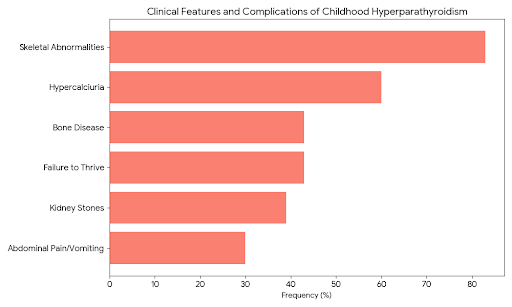

3. Pediatric vs. Adult Clinical Features

Children with parathyroid dysfunction, particularly hyperparathyroidism (PHPT), exhibit much more severe and symptomatic presentations than adults, who are often diagnosed incidentally during routine blood work.

Skeletal Involvement: In children, this often manifests as bone pain, structural deformities, and fractures. In adults, classic bone disease like osteitis fibrosa cystica is now rare (< 2\%).

Renal Involvement: Children have nearly three times the rate of nephrolithiasis (kidney stones) compared to adults when diagnosed with PHPT.

Clinical features and complications.

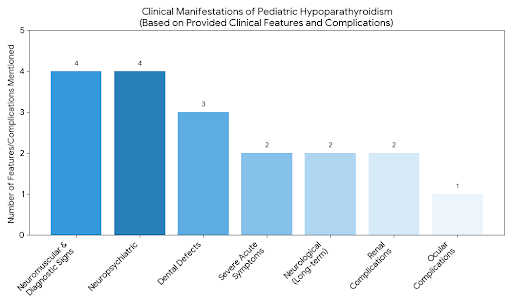

1. Hypoparathyroid Tetany (Low Calcium)

Hypoparathyroidism in children often stems from genetic syndromes (like DiGeorge syndrome), autoimmune destruction, or accidental damage during neck surgery. The hallmark of acute deficiency is tetany—a state of extreme neuromuscular irritability.

Clinical Features

Neuromuscular Irritability: The earliest signs are often paresthesia (tingling) around the mouth and in the fingertips/toes.

Tetany Attacks: This can progress to painful muscle spasms. A classic sign is carpopedal spasm, where the hands and feet tuck into a stiff, claw-like position.

Diagnostic Signs:

Chvostek Sign: Tapping the facial nerve causes the lip or cheek to twitch.

Trousseau Sign: Inflating a blood pressure cuff causes the hand to spasm into a "delivery" position.

Severe Acute Symptoms: Laryngospasm (vocal cord spasms causing high-pitched breathing or stridor) and generalized seizures.

Neuropsychiatric: "Brain fog," irritability, anxiety, and depression.

Long-Term Complications

Dental Defects: If it occurs during tooth development, children may have pitted enamel, delayed teething, or short tooth roots.

Ocular: Early-onset cataracts are common due to chronic calcium imbalances in the lens.

Neurological: Basal ganglia calcifications (calcium deposits in the brain) which can lead to movement disorders.

Renal: Treatment with calcium and Vitamin D often leads to nephrocalcinosis (calcium in the kidneys) or kidney stones because the lack of PTH causes the kidneys to "dump" calcium into the urine.

2. Hyperparathyroidism (High Calcium)

Primary hyperparathyroidism is rare in children and is frequently associated with genetic conditions like Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia (MEN) syndromes. Unlike adults, children are almost always symptomatic at the time of diagnosis.

Clinical Features

The symptoms are traditionally summarized as "Stones, Bones, Abdominal Groans, and Psychic Moans":

Renal (Stones): Excessive thirst (polydipsia) and frequent urination, often leading to kidney stones.

Skeletal (Bones): Bone pain, joint aches, and "pathological fractures" (broken bones from minor falls).

Gastrointestinal (Groans): Severe constipation, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. In rare cases, it can cause pancreatitis.

Psychological (Moans): Extreme fatigue, lethargy, memory issues, and "foggy" thinking.

Infantile Specifics: In neonates, this may present as failure to thrive, hypotonia (floppy baby), and respiratory distress.

Long-Term Complications

Skeletal Deformity: Chronic PTH excess "robs" the bones of calcium, leading to osteoporosis, rickets-like bowing of the legs, and stunted growth.

Renal Failure: Permanent kidney damage from chronic stone formation and calcification.

Cardiovascular: High calcium can lead to hypertension (high blood pressure) and heart rhythm abnormalities (shortened QT interval).

Risk Factors

Preterm Birth: Premature infants are at higher risk for transient hypocalcemia due to immature gland function.

Maternal Health: If a mother has untreated hyperparathyroidism, the high calcium crossing the placenta can suppress the fetus's parathyroid glands, leading to temporary tetany after birth.

Magnesium Deficiency: Low magnesium levels (hypomagnesemia) can prevent the parathyroid glands from releasing PTH and make the body resistant to the hormone's effects.

Conclusion

The management of parathyroid dysfunction in childhood—encompassing both hypoparathyroid tetany and hyperparathyroidism—presents a unique clinical challenge that necessitates a high index of suspicion. While these conditions represent opposite ends of the calcium homeostasis spectrum, they share a common requirement for precise, long-term monitoring to safeguard skeletal development and renal health.

Key Summary Points

Hypoparathyroid Tetany: Acute management focuses on the immediate reversal of neuromuscular irritability through cautious calcium supplementation. However, the long-term therapeutic goal remains a delicate balance: maintaining serum calcium in the low-normal range to prevent the development of nephrocalcinosis and permanent renal impairment.

Hyperparathyroidism: Whether primary (often due to adenomas) or secondary (linked to vitamin D deficiency or renal disease), childhood hyperparathyroidism demands a prompt investigation into underlying genetic etiologies, such as Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia (MEN) syndromes. Surgical intervention, when indicated, remains the definitive cure, provided it is performed by specialized pediatric surgical teams.

References

1.Alagaratnam, S., Brain, C., Spoudeas, H., Dattani, M. T., Hindmarsh, P., Allgrove, J., Van’t Hoff, W., & Kurzawinski, T. R. (2014). Surgical treatment of children with hyperparathyroidism: Single centre experience. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 49(10), 1539–1543

2.American Academy of Family Physicians [AAFP]. (2022). Parathyroid Disorders. American Family Physician, 105(3), 289–299.

3.Bilezikian, J. P., Khan, A. A., Silverberg, S. J., Fuleihan, G. E., Marcocci, C., Minisola, S., et al. (2020). Evaluation and Management of Primary Hyperparathyroidism: Summary Statement and Guidelines from the Fifth International Workshop. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 37(11), 2293–2314.

4.Misiorowski, W., Dedecjus, M., Konstantynowicz, J., Zygmunt, A., Kos-Kudła, B., Lewiński, A., Ruchała, M., & Zgliczyński, W. (2023). Management of hypoparathyroidism: a Position Statement of the Expert Group of the Polish Society of Endocrinology. Endokrynologia Polska, 74(5), 447–467.

5.Shoback, D. M., Bilezikian, J. P., Costa, A. G., Dempster, D., Dralle, H., Khan, A. A., et al. (2016). Presentation of Hypoparathyroidism: Etiologies and Clinical Features. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 101(6), 2300–2312.

6.Korkmaz HA, Ozkan B. Hypoparathyroidism in children and adolescents. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2023;28(3):159–167.

7.Parathyroid conditions in childhood. Pediatric Parathyroid Disease. PubMed review article summarizing pediatric hyperparathyroidism, surgery, and clinical aspects.

8.Shah I. Hypocalcemic Tetany in a 14-year-old girl. Pediatric Oncall Journal.

Pediatric case of hypoparathyroid tetany demonstrating clinical symptoms and management.

9.Wikipedia — Hyperparathyroidism & Adenoma of Parathyroid Gland

Useful for basic definitions, etiologies, and recognition of parathyroid adenoma causes.

10.Primary Hyperparathyroidism due to Parathyroid Adenoma in Children and Adolescents. Endocr Pract. 2024;30(6):564–568.