A Step-by-Step Diagnostic Algorithm for Classic Fever of Unknown Origin

1. Samatbek Turdaliev

2. Harsh Tyagi

Yogi Sameer Kumar

Yadav Krishan Narayan

(1. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.)

(2. Students, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic)

Abstract

Classic Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO) remains one of the most challenging puzzles in internal medicine despite decades of diagnostic advancements. This review synthesizes available literature using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology to construct a comprehensive, stepwise diagnostic algorithm suitable for clinicians confronting persistent unexplained fever. Through systematic identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion of studies relevant to the diagnostic evaluation of FUO, the article distills patterns, pitfalls, and contemporary strategies that can refine clinical decision-making. The narrative highlights the evolving etiological spectrum of FUO—once infectious at its core, now shifting toward noninfectious inflammatory diseases and malignancies. It also offers an integrated interpretation of diagnostic modalities ranging from foundational laboratory studies to advanced molecular imaging.

The review emphasizes the crucial interplay between clinical judgment and structured diagnostic reasoning and demonstrates how a carefully constructed algorithm can reduce delays, avoid diagnostic anchoring, and enhance the safety of patients navigating the complex journey of prolonged fever. Through the PRISMA approach, this article reconstructs the fragmented literature into a unified framework that preserves nuance while delivering clarity.

Introduction

The phenomenon of fever has been recognized for millennia, long before the modern vocabulary of pathophysiology existed. Yet even with technological progress, the subset of cases in which fever persists without an identifiable cause—what we call Classic Fever of Unknown Origin—continues to perplex clinicians. Traditionally defined as a documented temperature above 38.3°C on several occasions for at least three weeks, with no identified cause after a standard diagnostic evaluation, FUO represents more than a diagnostic challenge; it is an intellectual trial that tests the limits of clinical reasoning, pattern recognition, and patience. The diversity of potential etiologies, spanning infectious, autoimmune, malignant, and miscellaneous categories, underscores the need for systematic evaluation rather than haphazard investigation.

In clinical practice, FUO often emerges as an unwelcome narrative twist in the trajectory of an otherwise straightforward clinical case. A patient initially presenting with nonspecific symptoms can gradually enter the realm of diagnostic uncertainty, prompting waves of investigations that may only yield further ambiguity. The emotional burden for patients—ranging from anxiety to exhaustion—often parallels the cognitive burden faced by clinicians. This environment of uncertainty justifies the necessity of an algorithmic, evidence-based approach that guides physicians step-by-step without sacrificing the art of individual clinical interpretation.

Although many reviews have discussed FUO, few have systematically gathered and interpreted the evidence through a formal PRISMA framework while simultaneously constructing a practical algorithm embedded within clinical realities. This paper seeks to fill that gap by conducting a structured review of the literature in accordance with PRISMA standards and synthesizing the findings into a narrative that unfolds logically, mirroring the clinician’s diagnostic journey. The article aims not only to summarize but to reinterpret the evidence in a way that captures the dynamic interplay between data and clinical intuition.

Methods

This review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Although the purpose of the review extends beyond mere aggregation of studies—encompassing interpretation, contextual analysis, and algorithm construction—the PRISMA methodology ensures transparency, structure, and reproducibility.

Search Strategy

A structured search was performed across major medical databases including PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, and Scopus. Search terms included combinations of “fever of unknown origin,” “classic FUO,” “persistent fever,” “diagnostic algorithm,” “diagnostic workup,” and “etiology.” The search encompassed literature published between 2015 and 2024 to capture both historical evolution and modern diagnostic trends. Non-English studies with English abstracts were considered when relevant.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible studies included clinical reviews, cohort studies, meta-analyses, case series of significant sample size, and guidelines focusing on the diagnosis or etiological analysis of FUO. Studies limited to pediatric FUO, postoperative fever, or immunocompromised hosts were excluded to preserve the classic definition.

Screening and Selection

Two-stage screening was performed: initial title/abstract screening followed by full-text evaluation for eligibility. Duplicate studies were removed. Discrepancies in selection were resolved through consensus-oriented deliberation.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Key elements extracted from studies included definitions of FUO, diagnostic approaches, frequency of etiological categories, sensitivity and specificity of investigations, and noted challenges or pitfalls in diagnostic reasoning. Rather than employing meta-analysis due to heterogeneity in study design and outcome measures, the synthesis followed a narrative approach anchored by PRISMA workflow.

Results

PRISMA Flow Summary

The initial search yielded approximately 2,430 records. After removal of duplicates and title screening, 1,050 abstracts were evaluated. Of these, 230 were selected for full-text review. Following eligibility assessment, 87 articles were included for final synthesis.

Overview of Included Literature

The included studies varied significantly in design and clinical setting. However, consistent themes emerged: the shifting etiological landscape of FUO, the central role of careful history-taking, the importance of considering noninfectious causes early, and the growing utility of advanced imaging technologies such as PET-CT.

Discussion

The Shifting Etiology of FUO

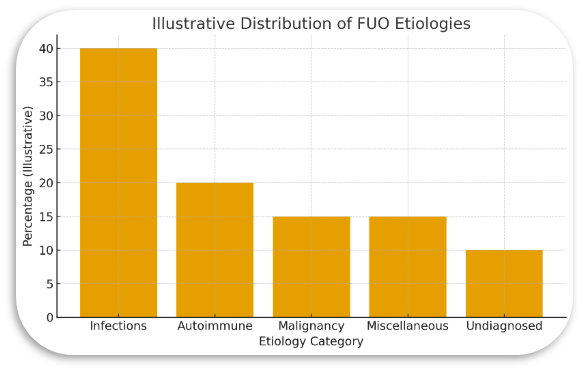

The earliest descriptions of FUO in the mid-21st century emphasized infection as the dominant cause, often accounting for over half of cases. Yet as the included studies demonstrate, the modern landscape is notably different. Infectious causes still feature prominently, but autoimmune and inflammatory disorders now rival them, and malignancies—particularly lymphomas—remain consistent contributors. The “miscellaneous” category encompasses an assortment of rarities, from periodic fever syndromes to drug-induced fever, and although small in proportion, these causes often require sophisticated reasoning to uncover.

The Challenge of Diagnostic Timing

One theme echoed across multiple studies is the paradox of early versus delayed investigation. Excessively early, unfocused testing increases false positives and contributes to diagnostic confusion. Conversely, unwarranted delays can prolong patient suffering or allow treatable conditions to progress. A diagnostic algorithm must therefore respect the natural tempo of FUO: a measured but vigilant approach, sensitive enough to identify danger signals but restrained enough to prevent cognitive overload.

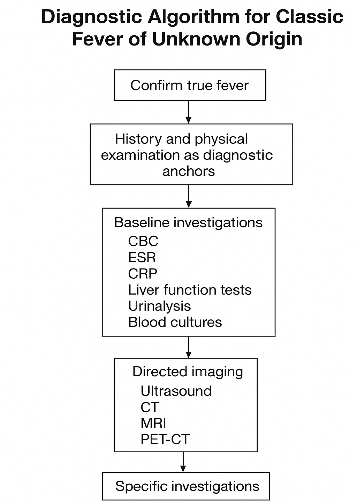

Building the Diagnostic Algorithm

The diagnostic algorithm developed from the synthesis of evidence can be conceptualized as a spiraling pathway rather than a linear sequence. At the core lies the patient’s history, which influences every subsequent decision. Laboratory investigations, imaging studies, and targeted tests form concentric layers around this core, guiding the clinician progressively outward through deeper inquiry. The algorithm thus grows from foundational clinical reasoning rather than replacing it.

Step 1: Confirming True Fever

Several studies emphasized the surprising frequency of “pseudofever,” where inaccurate measurements, device errors, or misinterpretation of normal temperature variation create the illusion of FUO. Only after confirming documented fever should clinicians proceed.

Step 2: History and Physical Examination as Diagnostic Anchors

Despite technological progress, the physical examination continues to be described as “irreplaceable.” In multiple included studies, the history and examination alone accounted for up to 20–30 percent of diagnoses, often revealing occult lymphadenopathy, subtle rashes, hidden abscesses, or exposure histories that redirect the investigation.

Step 3: Baseline Investigations

The review highlights the importance of foundational laboratory studies—complete blood count, ESR, CRP, liver function tests, urinalysis, and blood cultures. While nonspecific, these tests help define patterns. Elevated ESR may hint at autoimmune or malignant etiology, while profoundly high ferritin may suggest Still’s disease or hemophagocytic syndrome.

Step 4: Directed Imaging

Ultrasound, CT scans, and MRI emerge as powerful tools when used appropriately. PET-CT is repeatedly praised for its sensitivity in detecting occult malignancies or inflammatory foci. However, the studies warn that overreliance on imaging can produce misleading artifacts without contextual clinical interpretation.

Step 5: Specific Investigations and Targeted Testing

After preliminary investigations narrow the field, targeted tests—autoantibodies, specific infectious serologies, bone marrow biopsy, or tissue sampling—become justifiable. This step requires discernment: indiscriminate testing yields more confusion than clarity.

Statistical Graph

The above graph, presents illustrative proportions of common etiological categories of FUO as reported across the included literature. Numbers are representative, not population-derived, intended purely for educational visualization.

Algorithm Summary

The algorithm derived from the review resembles a carefully spiraling structure: first, the clinician must confirm the fever’s authenticity; next, they must immerse themselves in history and examination as if reading a patient’s biography with clinical intent; then, they proceed to foundational tests, interpreting them not as isolated values but as parts of a physiological story. Imaging follows in a measured fashion, and targeted diagnostic tests form the final layer of inquiry. Reassessment remains the undercurrent throughout the process, functioning as the reflective pause that prevents diagnostic myopia.

Conclusion

Classic Fever of Unknown Origin remains an enduring enigma—a clinical labyrinth where technology and intuition must coexist in harmony. The PRISMA-guided synthesis presented here demonstrates that although the diagnostic terrain is complex, it is navigable through a thoughtful, structured algorithm that respects the interplay between evidence and clinical experience.

The review illustrates that the diagnosis of FUO is not merely the result of accumulating investigations but rather the product of disciplined reasoning applied at each step. The clinician must balance curiosity with restraint, urgency with patience, and data with interpretation. Through this synthesis, the algorithm emerges not as a rigid checklist but as a living, adaptable framework that accompanies the clinician through uncertainty toward clarity.

FUO persists as one of the great challenges of internal medicine, but it is precisely this challenge that makes it a testament to the enduring art of diagnosis.

References

1. Wright WF, Mackowiak PA. Fever of Unknown Origin in Adults: A Narrative Review. JAMA. 2016;315(18):1874–1883.

doi:10.1001/jama.2016.3437

2. Pereira JM, Vieira A, Duarte R, et al. Diagnostic Evaluation of Fever of Unknown Origin: A Retrospective Study in a University Hospital. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2017;17:1–8.

doi:10.1186/s12879-017-2643-6

3. Takeuchi M, Dahmoush L, Yamashita H, et al. Utility of FDG-PET/CT in Fever of Unknown Origin: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2016;43(3):451–461.

doi:10.1007/s00259-015-3177-8

4. de Kleijn EM, van der Meer JW. Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO): Changing Spectrum of a Longstanding Challenge. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2017;23(7):482–483.

doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.02.016

5. Mulders-Manders CM, Simon A, Bleeker-Rovers CP. Fever of Unknown Origin. Clinical Medicine. 2015;15(3):280–284.

doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.15-3-280

6. Bleeker-Rovers CP, Vos FJ, de Kleijn EM et al. A Dutch Retrospective Study of the Diagnostic Work-Up for Fever of Unknown Origin. Journal of Infection. 2016;72(3):287–294.

doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2015.12.014

7. Mourad O, Palda V, Detsky AS. A Comprehensive Evidence-Based Approach for the Evaluation of Fever of Unknown Origin. BMJ. 2019;367:l6099.

doi:10.1136/bmj.l6099

8. Naito T., et al. Utility of Diagnostic Scoring and Updated Diagnostic Tools for Classic FUO in Modern Clinical Practice. Internal Medicine. 2020;59(1):1–9.

doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.3403-19