Acquired Hemolytic Anemia in Children

1. Rochelle Netto

2. Osmonova Gulnaz Zhenishbaevna

(1. Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.

2. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic)

Abstract

Acquired hemolytic anemia (AHA) in children is a wide-ranging collection of conditions that all have in common the premature elimination of red blood cells (RBC) caused by external agents. Congenital forms are very different from AHA, which is a result of immune dysregulation, infections, toxins, or systemic diseases. This article uses the IMRAD format to bring together current knowledge on the epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic methods, and treatment strategies for AHA in children. The review gives a detailed discussion of the two most common forms—Immune Hemolytic Anemia (IHA) and non-immune mediated hemolysis—with a wider view on new causes and the difficult management of these cases. The diagnostic methods applied are the critical direct antiglobulin test (DAT) among others, and in-depth molecular techniques. Depending on the aetiology, management may be by immunosuppression for autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), supportive care plus antimicrobial therapy for infection-induced cases or allowing for case by case. There have been advances, but there are still big difficulties in the treatment of resistant cases, reducing morbidity associated with treatment and knowing the long-term results. The review highlights the importance of a systematic, multidisciplinary approach and also points out the research directions that may lead to better outcomes for this vulnerable population.

Introduction

Hemolytic anemia (HA) is characterized by a pathological shortening of the red blood cell (RBC) lifetime, which is usually less than 120 days, and this leads to the development of anemia, the compensatory increase in reticulocyte count and the presence of biochemical parameters indicating RBC destruction. In infants and children, HA is a great challenge for diagnosis and treatment and is classified into the following categories: congenital (e.g., spherocytosis, sickle cell disease, G6PD deficiency) or acquired. Ac- quired Hemolytic Anemia (AHA) is caused by factors that act on a RBC from outside its body, causing its premature death while still in the blood circulation (intravascular) or in the spleen and liver (extravascular) - these latter being the main locations of the reticuloendothelial system. Although it is a less common cause of anemia in children than nutritional deficiencies or congenital forms, its sudden clinical presentation, possible rapid deterioration, and association with serious underlying conditions make it necessary to identify and provide correct treatment without delay.

The incidence of pediatric AHA is not completely understood because of its infrequent occurrence, wide range of causes, and differences in regions with regard to the onset of underlying triggers like infections. Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia (AIHA), which is a prominent subtype, is considered to have an incidence rate of 0.2-1.0 per 100,000 children annually, with a recognized two-peaked age distribution with peaks in early childhood (¡5 years) and again at adolescent age. It is very unusual for AIHA to be diagnosed in the first year of life. AIHA can have an idiopathic nature or in about 30- 50% of the pediatric cases, it is due to some other disease, thus considered as secondary. Possible common associations include recent or ongoing infections (viral or bacterial), immunodeficiency (e.g., Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome [ALPS], Common Variable Immunodeficiency [CVID]), autoimmunity diseases (most importantly systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]), and in addition to that, it is a malignancy (mainly lymphomas). AHA non-immune, for example, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) that occurs in Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS), has different epidemiological patterns which are often associated with specific infectious outbreaks.

The clinical impact of AHA in pediatric patients can be enormous. It might show up as a critical medical emergency that very quickly takes an acute anemia route of the highest degree which in turn causes breathing and heart rate to speed up, then pallor, finally, lethargy and even possibly hemodynamic instability and heart failure. Chronic hemolysis may still not be so acute but still there are the risks of impaired growth, loss of physical activity tolerance, tiredness, jaundice, and complications like pigment gallstones and chronic leg ulcers in very serious situations. The whole procedure of diagnosis is very complicated and needs careful and skillful working out of congenital hemolytic anemias to the various acquired causes, a difficult task indeed with the presence of overlapping clinical and laboratory features. Treatment is not any easier, it’s a juggling act of the urgency in correcting anemia with the underlying etiology which often needs immunosuppressive therapies that have such significant side-effect profiles that concern over the health of a developing child becomes even more acute.

The goal of this article is to provide a more extensive and thorough academic review of the acquired hemolytic anemia in children. It will not only be based on the main concept but also intimate the pathophysiological mechanisms more profoundly, suggest a more exhaustive division of causes, and elaborate on the modern diagnostic pathways with an emphasis on odd cases, and critically assess the changing evidence-based treatment practices including new biologics. The author also will talk about prognostic factors, long- term consequences, and quality of life issues, pointing out where the present research is concentrated and where knowledge gaps still exist.

Methods

To really grasp the AHA, one must take a systematic route that is built on the pathophysiological processes that result in the destruction of RBCs. The subsequent enlarged classification showcases the said mechanisms and their medical correlates.

1. Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia (IHA)

IHA is the result of body immunity that targets RBC antigens, be they self (autoimmune), drug-modified, or foreign (alloimmune). The destruction starts with the binding of antibodies (IgG, IgM, or very rarely IgA) through either complement-mediated lysis of RBCs in the blood vessels or extravascular phagocytosis by cells that have receptors for the antibodies (Fc-receptor-mediated).

• Warm Antibody AIHA: It is the most common type in children, being responsible for ∼70-80% of AIHA cases. The pathogenic IgG antibodies bind best at 37°C to the protein antigens on the RBC membrane, most often in the Rh system (for example, e, c, D) among antigen types. The coating of antibodies (sensitization) leads to the recognition of macrophages in the spleen through Fcγ receptors. Partial phagocytosis occurs and the RBC loses some of its membrane surface area, which transforms the biconcave disc into a rigid spherocyte that is afterwards caught and killed in the splenic cords. Prior to that, the activation of complement may be initiated but is mostly stopped at the C3b stage due to the presence of the regulatory proteins; however, the C3b-coated RBCs can still be taken out of circulation by macrophages in the liver (extravascular hemolysis). The process is characterized by spherocytosis on the blood smear and a positive DAT for IgG with or without C3d.

• Cold Antibody AIHA (Cold Agglutinin Disease - CAD): The process involves IgM antibodies that have a binding range from optimal at 0-4°C to reactivity at 28-31°C (thermal amplitude). The specific binding is to carbohydrate antigens (e.g. I/i system). In peripheral body parts like fingers and tops where the temperature is cooling down, the IgM attaches to RBCs, which results in agglutination and activation of the classical complement pathway. If the process reaches the point where the membrane attack complex (C5b-9) is formed, then hemolysis occurs within the blood vessels. However, more often than not, the complement is activated only to a point where C3b is left on RBCs. While the RBCs are passing through the warmer central circulation, the IgM comes off but C3b stays put, hence the reason for extravascular hemolysis mainly in the liver. The classic lab findings are peripheral blood smear showing RBC clumping (often dispersing on heating), a DAT positive for C3d only (IgM comes off at 37°C), and very high cold agglutinin titer.

• Paroxysmal Cold Hemoglobinuria (PCH): A historically significant, now un- common type of AIHA in children that is often post-viral. It is the Donath- Landsteiner (D-L) antibody that mediates the condition; this is a biphasic IgG antibody that binds to the P blood group antigen on RBCs when it is cold and then fixes complement, which in turn lyses the cell during rewarming, eventually leading to severe intravascular hemolysis and hemoglobinuria. The diagnosis is established through the Donath-Landsteiner test.

• Drug-Induced Immune Hemolytic Anemia (DIHA): A significant and potentially overlooked source. This condition can manifest through three main mechanisms:

1. Drug Adsorption (Hapten) Model: E.g., high-dose penicillin. Thanks to covalent binding, the drug attaches to the RBC membrane, and once the specific antibodies are there (usually IgG), they bind to the drug-membrane complex leading to extravascular hemolysis which is similar to warm AIHA. Furthermore, the direct Coombs test (DAT) is positive for IgG.

2. Immune Complex Model: E.g., ceftriaxone, quinine. The drug binds with plasma proteins very loosely and IgM antibody production is the result. In plasma, drug-antibody (immune) complexes are formed which non-specifically adsorb to RBC membranes through complement receptors initiating a powerful complement activation and hence acute, sometimes severe intravascular hemolysis. The DAT is usually positive for C3d only.

3. Autoantibody Model: E.g., alpha-methyldopa. The medication compels the body to lose its immune tolerance, thereupon generating warm-reactive autoantibodies that are exact copies of those in primary warm AIHA and are hence indistinguishable from them. Hemolysis is likely to last for weeks even after the drug is stopped. The DAT test comes back positive for IgG.

• Alloimmune Hemolytic Anemia: This type of anemia is not “acquired” in the standard manner; however, it implicates an acquired immune response. The most noteworthy cases include Hemolytic Disease of the Fetus and Newborn (HDFN), where this condition is caused by maternal IgG antibodies that pass through the placenta, and blood transfusion reactions that occur due to mismatch of blood products.

2. Non-Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia

This category includes hemolysis where the RBC was subjected to a direct physical, chemical, infectious, or metabolic injury.

• Microangiopathic Hemolytic Anemia (MAHA): Red blood cell (RBC) destruction due to mechanical forces happens as the cells move through a very tiny and abnormal blood vessel which has a thrombus (coagulated blood) or is ruptured from one side. The main finding leading to diagnosis is the presence of schistocytes (helmet cells, triangular fragments).

– Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS): The leading cause of MAHA in children. Typical (diarrhea-positive) HUS is generally associated with Shiga- toxin producing E. coli (STEC) infection. The toxin binds to the glomerular endothelial cells and causes them to die leading to the formation of a clot in the microvasculature and hence, mechanical hemolysis of RBCs occurs.

– Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP): Causes severe deficiency of ADAMTS13, which is a protease that cuts von Willebrand factor multimers. Due to the absence of this enzyme, there is more platelet aggregation in the small blood vessels.

– Other causes such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), malignant hypertension, prosthetic heart valves, and giant cavernous hemangiomas (Kasabach-Merritt syndrome) may also be included.

– Infectious Agents: These microorganisms are responsible for hemolysis in different ways:

– Direct Invasion and Destruction: Plasmodium spp. (malaria) reproduce inside the RBCs and then rupture them; Bartonella bacilliformis (Oroya fever) sticks to and harms the RBCs.

– Toxin Production: Clostridium perfringens releases a lecithinase (alpha- toxin) that acts as an enzyme to destroy the RBC lipid membrane.

– Immune-Mediated Triggering: Mycoplasma pneumoniae brings about the formation of cross-reactive cold agglutinins (anti-I). Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) and Cytomegalovirus (CMV) can activate both cold AIHA and warm AIHA simultaneously.

• Toxic/Oxidant Injury: This process results in the oxidation of hemoglobin and the RBC membrane cytoskeleton, causing the cell to die.

– For individuals with G6PD deficiency: The use of oxidant drugs (sulfon-amides, antimalarials such as primaquine), eating fava beans, or being exposed to naphthalene leads to a collapse of the reduced glutathione defense system. The denatured hemoglobin then forms Heinz bodies, and the damaged RBCs are filtered out by the spleen, thus seen as “bite cells” or “blister cells.”

– For people with normal G6PD: These toxins such as chlorates, arsine gas, or copper (from Wilson’s disease or contaminated dialysis water) can create a situation where severe oxidant stress leads to hemolysis as well.

• Hypersplenism: This refers to an overactive spleen that is enlarged and causes the trapping and destruction of RBCs (and other blood cells) in it. It is one of the causes of pancytopenia associated with hemolysis and is due to conditions like portal hypertension, lysosomal storage diseases (e.g., Gaucher’s), and chronic infections (e.g., visceral leishmaniasis).

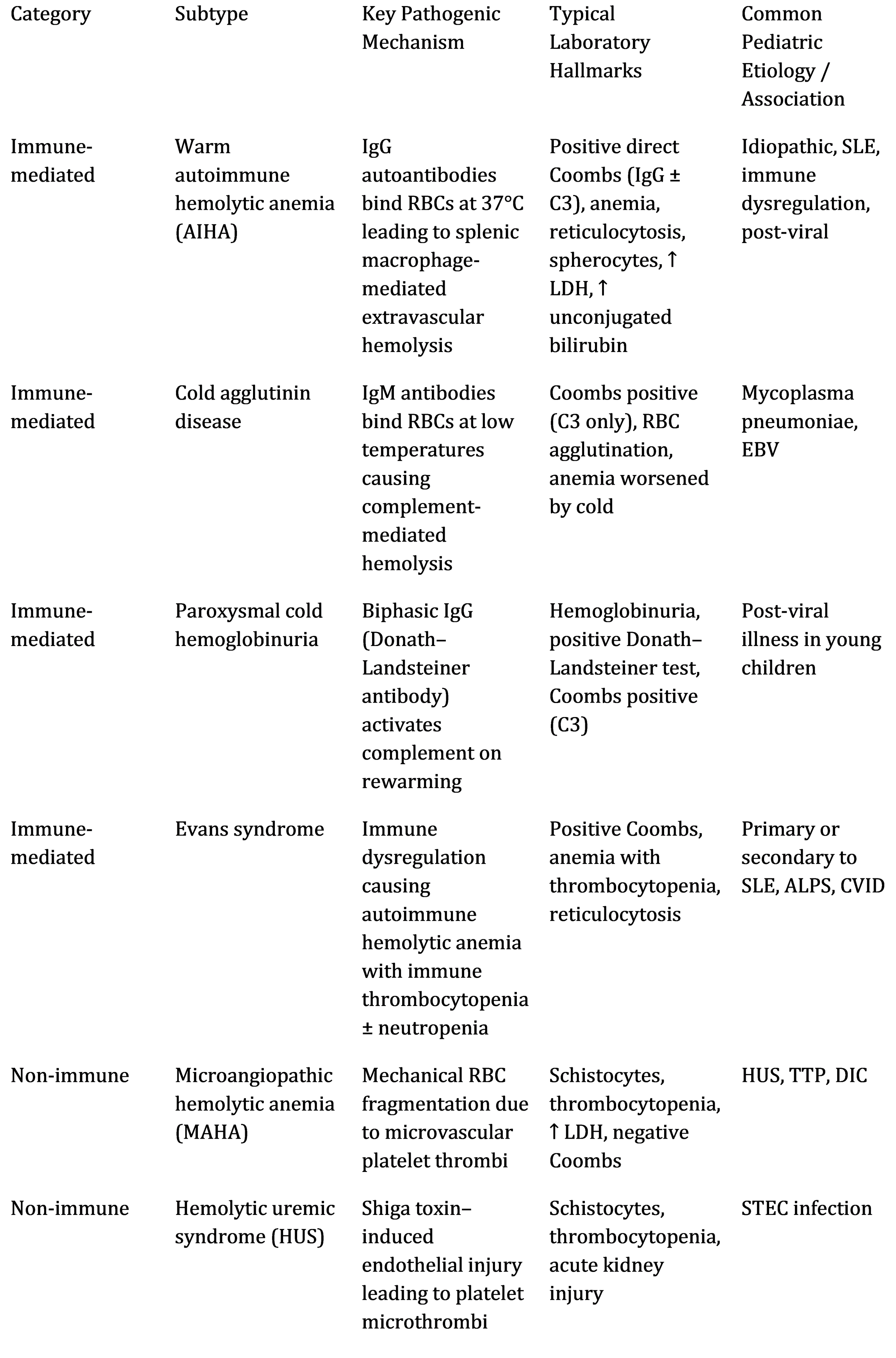

Table 1: Expanded Classification and Mechanisms of Acquired Hemolytic Anemias in Children

Results

Clinical Presentation: A Spectrum from Indolent to Fulminant

AHA in children may present differently, with the rate of hemolysis (acute vs. chronic), its site (intravascular vs. extravascular), and the underlying cause being the main factors determining the clinical picture.

• General Symptoms of Anemia and Hemolysis:

– Anemia: The child may appear pale, be very tired, not want to play, feel dizzy, be irritable, and have headaches. In infants, symptoms may include poor feeding and failure to thrive. In case of acute, severe anemia, symptoms are increased heart rate, increased respiratory rate, breathlessness, heart murmurs due to increased blood flow, and/or signs of decreased blood flow to organs (cold hands and feet, slow refill of capillaries) or to the heart working more than normal (gallop rhythm, enlargement of the liver).

– Hemolysis: Neonatal jaundice (due to high levels of unconjugated bilirubin in the blood) is usually the first sign observed in newborns. The infant has yellow skin and whites of eyes. Dark urine may be due to excess urobilinogen or, in intravascular hemolysis, hemoglobinuria/hemosiderinuria; and splenomegaly (common in extravascular hemolysis like warm AIHA) and, less frequently, hepatomegaly.

• Etiology-Specific Clinical Features:

- Cold AIHA/CAD: Symptoms often made worse by cold weather. Patients may show signs of peripheral blood circulation problems, such as bluish discoloration of the extremities, skin mottle, net-like skin discoloration, and symptoms resembling those of Raynaud’s disease (pain, numbness, color change in fingers, toes, ears, nose). Hemoglobinuria may be episodic in nature, related to cold exposure.

– Paroxysmal Cold Hemoglobinuria (PCH): The classic presentation consists of highly pronounced and sudden attacks of symptoms that alternate with complete relief: chills, fever, pain in the back/legs, cramps in the abdomen, and dark red/brown urine (hemoglobinuria) after being cold or even after having a slight virus.

– MAHA (e.g., HUS/TTP): The classical pentad for TTP (fever, MAHA, thrombocytopenia, renal dysfunction, neurological symptoms) is very often not complete, particularly in the case of children. HUS usually starts with bloody diarrhea as a prodrome, then comes pallor, petechiae, oliguria, and hypertension.

– Infection-Associated: Fever, malaise, respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms, which are typical of the infection, are evident along with the signs of hemolysis.

– Evans Syndrome: Presents mixed signs of anemia and thrombocytopenia (bruising, petechiae, mucosal bleeding).

Diagnostic Evaluation: A Stepwise Algorithmic Approach

To confirm hemolysis, the identification of its mechanism and the unearthing of the underlying cause is highly dependent on the systematic and tiered diagnostics approach.

Step 1: Confirm the Presence of Hemolysis.

• Complete Blood Count (CBC) & Reticulocyte Count: Normocytic or macrocytic anemia (reticulocytotic leads to macrocytosis). A corrected reticulocyte count or reticulocyte production index (RPI) ¿3% points to an adequate response from the bone marrow. The occurrence of reticulocytopenia on the first visit is a very bad sign. It indicates that the patient has parvovirus B19-induced transient aplastic crisis, an antibody against erythroid precursors, or Diamond-Blackfan anemia aggravated by stress.

• Peripheral Blood Smear (Microscopy): A method that cannot be replaced.

– Spherocytes: Imply the occurrence of extravascular hemolysis, especially from warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) (differentiation from hered- itary spherocytosis is vital).

– Schistocytes: 1% is a strong indicator of MAHA.

– Agglutination: Either rouleaux formation or true clumping is indicative of the presence of cold AIHA.

– Polychromasia: Signifies reticulocytosis.

– Parasites: (Plasmodium, Babesia).

– Heinz bodies (identified with special staining): Point to oxidant injury.

– ”Bite” cells or ”blister” cells: Noted in G6PD deficiency following oxidant stress.

• Biochemical Markers of Hemolysis:

– Increased Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH): A product of lysed RBCs; markedly elevated in intravascular hemolysis and MAHA.

– Decreased Serum Haptoglobin: Captures the free hemoglobin released; levels drop soon and the haptoglobin level is a distinguishing sign for intravascular hemolysis. It can also be low in extravascular hemolysis. It is an acute-phase reactant and may be normal or elevated in concurrent inflammation/infection.

– Increased Indirect (Unconjugated) Bilirubin: Resulting from heme degradation.

– Increased Serum Hemoglobin & Hemoglobinuria/Hemosiderinuria:

The most straightforward evidence of intravascular hemolysis.

Step 2: Determine the Mechanism of Hemolysis (Immune vs. Non-Immune).

• Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT or Direct Coombs Test): The decisive test for IHA. It identifies whether there are antibodies or complement proteins that have attached to the patient’s RBCs in vivo.

– Pattern Interpretation:

∗ IgG only: Very indicative of warm AIHA or drug-induced (hapten/autoantibody model).

∗ C3d only: Indicates cold AIHA, PCH, or drug-induced (immune complex model).

∗ IgG + C3d: Present in warm AIHA, mostly indicating more severe disease.

∗ Negative DAT: Does not exclude AIHA. ”DAT-negative AIHA” is responsible for about 5-10% of cases and can be as a result of low-affinity antibodies, IgG subclass composition (e.g., IgG4 binds complement poorly), or low density of antibody on the RBC surface which is below the de- tection threshold of standard DAT. More sensitive techniques (e.g., flow cytometry, enzyme-linked antiglobulin test) may be necessary.

• Indirect Antiglobulin Test (IAT or Indirect Coombs): It measures the number of unbound antibodies in a patient’s serum. It is mainly used for the identification of antibodies in transfusion medicine and for the detection of alloantibodies. In warm AIHA, the serum is frequently containing pan-reactive autoantibodies that are interacting with all normal RBCs, thus complicating cross-matching.

Step 3: Identify the Specific Etiology.

This process is determined by the medical history, physical examination, DAT results, and peripheral blood smear.

– DAT Positive (IHA):

– Infection Workup: Screening for viral infections such as EBV, CMV, Parvovirus B19, HIV, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae serology/PCR, plus VDRL/RPR (for syphilis in congenital cases).

– Autoimmunity/Immunodeficiency Work-up: Testing for autoantibodies (ANA, anti-dsDNA), complement levels (C3, C4, CH50), quantitative immunoglobulins, and lymphocyte subset analysis. Testing for ALPS (Fas-mediated apoptosis, vitamin B12, soluble FAS ligand).

– Drug History: A thorough assessment of all medications, which includes OTC and herbal remedies, that are taken within the last few weeks to months.

– Imaging: A chest X-ray or abdominal ultrasound/CT may be performed if a tumor or other malignant condition is considered (e.g., persistent lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms).

• DAT-Negative or Suggestive of Non-Immune Hemolysis:

– MAHA Work-up: Testing for stool culture/PCR for STEC, ADAMTS13 activity and inhibitor assay (for TTP), coagulation profile (for DIC), renal function, blood pressure.

– Infectious Work-up: Thick and thin blood smears for malaria, cultures as indicated.

– Toxic/Oxidant Work-up: G6PD activity assay (it is crucial to wait for 2-3 months after the hemolytic crisis for a reliable result in males since reticulocytes have higher activity), history of toxin exposure.

– Congenital Causes: Testing with osmotic fragility, eosin-5-maleimide (EMA) binding test (for hereditary spherocytosis), hemoglobin electrophoresis/HPLC (for sickle cell/thalassemia), all of which may present with acute exacerbations mimicking AHA.

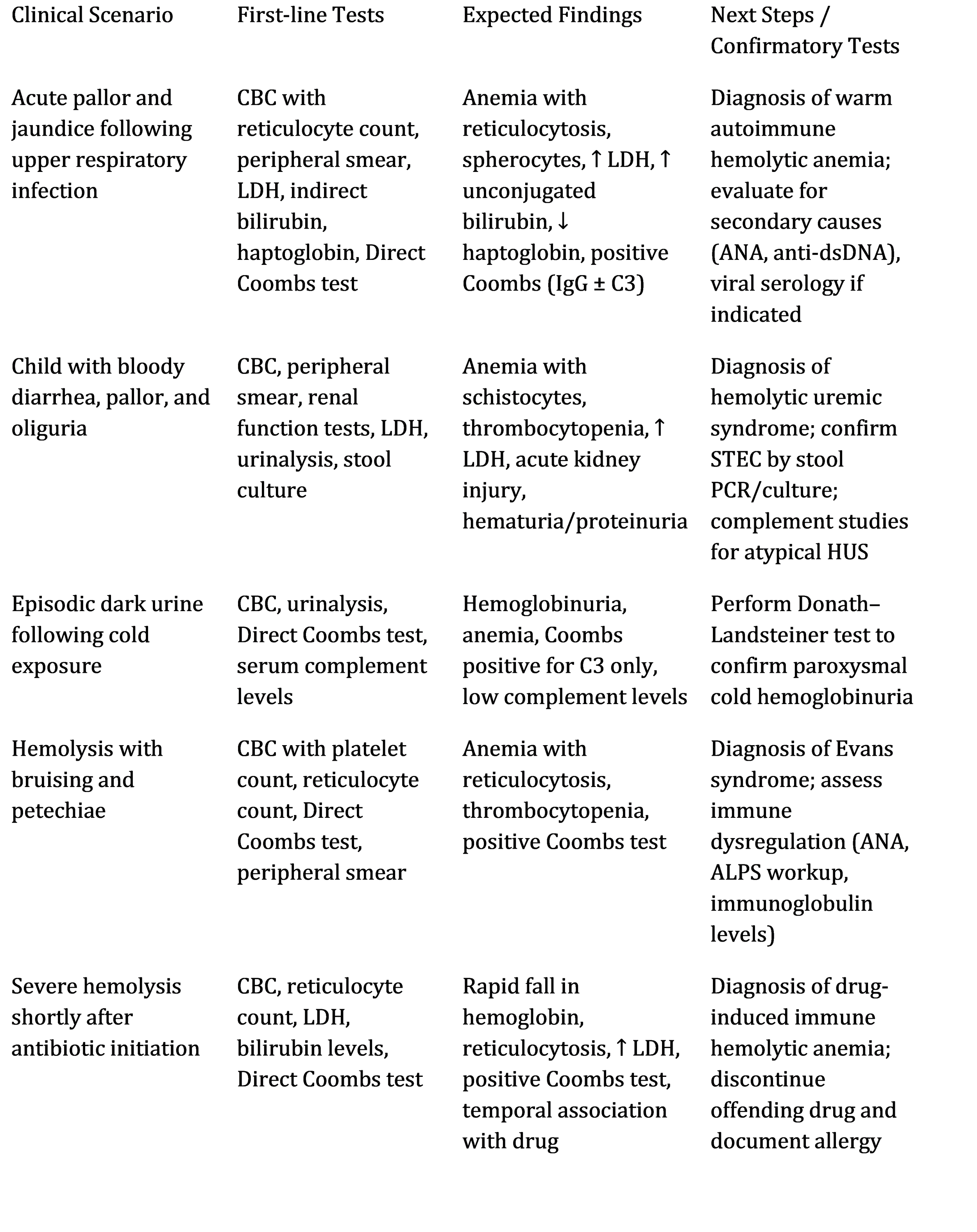

Table 2: Diagnostic Algorithm and Key Differentiating Features

Discussion

Management Principles: Etiology-Driven and Escalating

The treatment of AHA must be individualized according to its type and severity, with a careful weighing of the effectiveness against the possible toxicity.

1. Supportive and General Care:

• Transfusion Therapy: It is used when there is symptomatic anemia that causes discomfort (tachycardia, tachypnea, fatigue precluding ambulation, and heart failure). However, in IHA, it has a high-risk because of:

1. The difficulty in cross-matching (pan-agglutinating autoantibodies).

2. Alloimmunization risk.

3. Hemolysis potential exacerbation.

Protocol: Preferably, use extended phenotyped, least-incompatible RBCs, trans- fuse slowly (e.g., 1-2 mL/kg/hr initially), under close monitoring. For cold AIHA, use an in-line blood warmer. The objective is to lessen the symptoms, not to achieve normal hemoglobin levels.

• Folate Supplementation: 1-5 mg per day for erythropoiesis support.

• Infection Management: Prompt treatment of identified infections (e.g., azithromycin for Mycoplasma).

• Avoidance: Of harmful drugs or exposure to cold, if applicable.

2. Management of Immune-Mediated AHA (AIHA):

• First-Line Therapy:

– Corticosteroids: Safety first in warm AIHA. Mantle of therapy is held by Prednisone (1-2 mg/kg/day, max 60-80 mg/day) gets remission in ∼70-85% of kids and is criminally easy to use with just very few weeks (1-2) to see the results getting more visible. Plus, it is highly recommended to preemptively secure the area of relapse through a slow taper of 4-6 months. The situation can also be reversed by administering large doses of IV methylprednisolone (10- 30 mg/kg/day for 3-5 days) in case of severely and dangerously thrombosed areas.

– For Cold AIHA/PCH: Cold climate is unavoidable anyways. Steroids don’t work usually. The sick one needs to be pampered and given blood (after heating it up) in case of really getting severe with the nightmare of PCH because the illness tends to go away on its own after some time usually post- infection.

• Second-Line Therapy (Steroid-Refractory, Dependent, or Relapsing Disease):

– Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG): Steroids are usually taken as an adjunct in this case. Thus, IVIG is still the main option for severe warm AIHA treatment (0.8-1 g/kg/day for 1-2 days). Mechanism may involve Fc receptor blockade and immunomodulation. Response can be rapid but transient.

– Rituximab: Allotment of ’anti-CD20’ monoclonal antibodies that obliterate B-cells. It has changed the whole scenario of second-line therapy for both warm and cold AIHA in children. The medication is given (375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 doses) which prosecution leads to sustained responses in 70-80% of the pediatric warm AIHA cases, with a fair safety profile. It is getting more and more recognition as a preferred second-line agent over traditional immunosuppressants.

• Third-Line & Subsequent Therapies:

– Other Immunosuppressants: Mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, azathioprine, and cyclophosphamide are not only used alone but most often com- bine them with steroids. Sirolimus (mTOR inhibitor) has shown remarkable efficacy in ALPS-associated and refractory cytopenias including Evans Syn- drome by correcting the underlying T-cell dysregulation.

– Splenectomy: Current practice is to consider this procedure only for older children with long-term, debilitating, and medically non-responsive warm AIHA after thorough discussions. The main risks involved are the use of antibiotics and vaccinations throughout life to prevent susceptibility to bacteria with capsules, thromboembolism, and surgical complications. It has no effect at all in the case of cold AIHA.

– Complement-inhibiting therapies: These will be the first line of treatment, especially in terms of their application for diseases dependent on the complement system.

∗ Eculizumab (anti-C5): It is very efficient in treating atypical HUS and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH). Its application in warm AIHA that is not responding to treatment as well as cold agglutinin disease is hopeful but there are not many studies involving children that can provide evidence. It is an inhibitor of the terminal complement and hence ceasing intravascular hemolysis.

∗ Sutimlimab (anti-C1s): It only blocks the classical complement route at C1s. It has been recently authorized for adults with cold agglutinin disease and is showing rapid effectiveness; pediatric trials are still pending.

– Plasma exchange (PLEX): In the case of a severe, acute intravascular hemolysis (for instance, in the case of severe cold AIHA, PCH, immune com- plex DIHA) it can save lives as it works very fast in the elimination of pathogenic antibodies and complement components. It is also the first-line treatment for TTP (in combination with corticosteroids and later rituximab).

3. Management of Non-Immune AHA:

• MAHA: Therapy is for the specific cause and is made up of supportive measures (give fluids, do not give antibiotics/antimotility agents) for the typical STEC-HUS; plasma exchange and immunosuppression for TTP; and fixing the underlying reason in the case of DIC.

• Infectious: Antimalarials and suitable antibiotics (Clostridium, Bartonella) are provided.

• Toxic: The poisoning agent is removed, and supportive care is given. In G6PD deficiency, one is to avoid oxidant triggers.

Prognosis, Complications, and Long-Term Follow-up

The prognosis is very different. Acute post-infectious AIHA (e.g., Mycoplasma-associated CAD, viral PCH) is often completely resolved with an excellent prognosis. Patients with chronic primary warm AIHA and Evans Syndrome usually go through a relapsing- remitting cycle, and some of the children will be on long-term immunosuppression.

• Acute Complications: Severe anemia (cardiac failure, cognitive impact of hypoxia), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) from hemolysis, and acute renal injury due to hemoglobinuria.

• Chronic Complications:

– Thromboembolism: Warm AIHA has a significantly increased risk, espe- cially post-splenectomy. Anticoagulants may be given prophylactically in high- risk areas.

– Cholelithiasis: Pigment gallstones as a result of chronic hyperbilirubinemia.

– Transfusion-related: Iron overload (hemosiderosis) and alloimmunization.

– Treatment-related: Infections due to immunosuppression, growth retardation, osteoporosis, hypertension, diabetes, and avascular necrosis from corticosteroids. Certain agents like cyclophosphamide are associated with secondary malignancies.

• Mortality: Current reports indicate that the mortality rate is less than 10%, but this is not the case in refractory ones, Evans Syndrome, and patients who suffer from severe underlying conditions such as cancer.

Current Research and Future Directions

Research is rapidly advancing our understanding and treatment of AHA.

1. Novel Therapeutic Agents: Fostamatinib, a Syk inhibitor, is one such drug that has been shown to be effective in refractory warm AIHA adults by blocking FcγR signaling in macrophages. Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor that selectively kills plasma cells, is currently being studied in refractory situations. Besides, other biologics, like rituximab and complement inhibitors, are being tested.

2. Precision Diagnostics and Medicine: Research at the level of genetic and proteomic biomarkers is being conducted to predict the progression of the disease as well as the response to specific therapies (e.g., which patients will benefit from rituximab vs. those who need earlier complement inhibition). The use of genomic sequencing is helping to establish the relationship between immune dysregulation syndromes and AHA.

3. Understanding DAT-Negative AIHA: Flow cytometry using monoclonal anti- bodies to specific IgG subclasses, and techniques to isolate antibodies bound to cells, are increasing the detection and illuminating the pathophysiology of this disease.

4. Pediatric-Focused Clinical Trials: There is an urgent need for the development of evidence-based pediatric-specific protocols regarding drug sequencing, dosing, and duration of therapy through conducting prospective, multicenter trials.

5. Long-Term Outcomes Research: Studies exploring the neurodevelopmental, cardiovascular, and quality-of-life outcomes of children who have experienced chronic or severe AHA will be necessary to determine the proper course of action for lifelong care.

Conclusion

Acquired hemolytic anemia in children is a complex, multifactorial disorder that requires an elaborate and methodical approach from the clinician. The diagnosis is essentially based on an extensive understanding of the disease’s physiology, which leads to a lab- oratory evaluation that is performed in the order of blood count and peripheral smear and relies on the skillful interpretation of the Direct Antiglobulin Test. It is necessary to make a clear separation between immune and non-immune mechanisms, pointing further to the exact cause—autoimmune dysregulation, infection, microangiopathy, or toxic exposure—and to eventually start the right therapy that could be lifesaving.

Practices in the treatment area have shifted from the use of blunt immunosuppressive therapies such as high-dose steroids and splenectomy to the application of a more selective and immune-based therapeutic management. The introduction of rituximab as a very effective second-line agent and the arrival of complement inhibitors like eculizumab and sutimlimab are examples of this swing towards tailored medicine. These breakthroughs are expected not only to bring about a greater response rate but also to provide safer pro- files in the long run—an important factor in children. But there are also many difficulties, particularly in the case of refractory Evans Syndrome, managing chronic complications like thrombosis and treatment-related morbidities, and ensuring a smooth transition of care into adulthood.

Strong translational and clinical research is the foundation for future advancements. In particular, the comprehensive understanding of the genetic and molecular mechanisms of immune dysregulation, the performance of properly controlled pediatric clinical trials for new medications, and the execution of prolonged monitoring studies will all play a significant role in the improvement of diagnosis, treatment approach, and finally, the children who suffer from acquired hemolytic anemia will experience a healthier life with better quality. The management of this condition is neither a nor an experiment but rather a clear indication of the critical place of hematology as an always necessary and very important discipline, which balances basic immunology and the most sophisticated laboratory medicine with the most humane, patient-centric, holistic medical care.

References

1. Barcellini, Wilma, and Bruno Fattizzo. “Clinical Applications of Hemolytic Mark- ers in the Differential Diagnosis and Management of Hemolytic Anemia.” Disease Markers, vol. 2015, 2015, Article ID 635670. doi:10.1155/2015/635670.

2. Berentsen, Sigbjørn, and Anita Hill. “How I Manage Cold Agglutinin Disease.”

British Journal of Haematology, vol. 193, no. 2, 2021, pp. 245–255. doi:10.1111/bjh.17144.

3. Hill, Anita, et al. “How I Treat Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia in Children.”

Blood, vol. 139, no. 15, 14 Apr. 2022, pp. 2271–2280. doi:10.1182/blood.2021015113.

4. Ja¨ger, Ulrich, et al. “Diagnosis and Treatment of Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia in Adults: Recommendations from the First International Consensus Meeting.” Blood Reviews, vol. 41, 2020, p. 100648. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2019.100648.

5. Kalfa, Theodosia A. “Warm Antibody Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia.” Hematol- ogy: American Society of Hematology Education Program, vol. 2016, no. 1, 2016,

pp. 690–697. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.690.

6. Miano, Maurizio. “How I Manage Evans Syndrome and AIHA Cases in Chil- dren.” British Journal of Haematology, vol. 172, no. 4, 2016, pp. 524–534. doi:10.1111/bjh.13866.

7. Neunert, Cindy, et al. “American Society of Hematology 2019 Guidelines for Im- mune Thrombocytopenia.” Blood Advances, vol. 3, no. 23, 10 Dec. 2019, pp.

3829–3866. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000966.

8. Rogers, Zara R., and Bertil E. Glader. “Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia.” In Nathan and Oski’s Hematology and Oncology of Infancy and Childhood. 8th ed., edited by Stuart H. Orkin et al., Elsevier Saunders, 2015, pp. 487–510.

9. Roth, Alexander, and Ulrich J. Barcellini. “The Role of Complement in Autoim- mune Hemolytic Anemia.” Transfusion Medicine Reviews, vol. 34, no. 1, 2020, pp. 4–11. doi:10.1016/j.tmrv.2019.08.003.

10. Russo, Giovanna, et al. “Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia in Childhood: A Multi-

center Experience.” Frontiers in Pediatrics, vol. 8, 2020, p. 575–579. doi:10.3389/fped.2020.57537

11. Zanella, Alberto, and Wilma Barcellini. “Management of Immune Hemolytic Ane- mias.” Hematology: American Society of Hematology Education Program, vol. 2021, no. 1, 2021, pp. 709–717. doi:10.1182/hematology.2021000306.

12. Zeller, Michael P., et al. “Drug-Induced Immune Hemolytic Anemia: A 10-Year Retrospective Analysis.” Transfusion, vol. 62, no. S1, 2022, pp. S124–S134. doi:10.1111/trf.16931.

13. Liebman, Howard A., and Michael J. Weitz. “Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia.” Medical Clinics of North America, vol. 101, no. 2, 2017, pp. 351–359. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2016.09.