Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO): A Differential Diagnostic Challenge

1. Dr. Samatbek Turdaliev

2. Priya Yadav

Kanchan Sheshma

(1. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic

2. Students, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.)

Abstract

Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO) is a complex and challenging clinical entity defined by a temperature greater than 38.3°C (101°F) on several occasions, lasting longer than three weeks, and failing to yield a diagnosis despite one week of focused, intensive inpatient or structured outpatient investigation. The differential diagnosis for FUO is vast, traditionally encompassing four major etiological categories: Infections, Malignancies, Connective Tissue Diseases (CTDs)/Autoimmune Conditions, and Miscellaneous disorders. This article provides an analysis focusing on the differential diagnostic pathway for classical FUO. A detailed examination is made of key examples within the infectious (e.g., Tuberculosis, HIV infection), oncological (e.g., lymphomas), constitutional (e.g., drug-induced), and allergic/autoimmune (e.g., Still's disease) categories. The synthesis emphasizes the importance of a meticulous history, repetitive physical examinations, and a tiered, strategic use of advanced diagnostic tools, including modern imaging and molecular assays. The persistence of FUO often reflects the rarity or atypical presentation of common diseases, underscoring the necessity for a systematic and integrated approach to avoid unnecessary invasive procedures and achieve timely therapeutic intervention.

Introduction: Defining the Diagnostic Maze of FUO

Fever, or pyrexia, is one of the most common presenting symptoms in medical practice, representing a complex biological response, primarily mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1, IL-6, TNFα), that act upon the thermoregulatory center in the anterior hypothalamus. The elevation of the body's thermoregulatory set point results in a systemic response aimed at heat conservation and production. While the etiology of most acute febrile episodes is quickly ascertained through routine history, physical examination, and basic laboratory investigations—often attributable to common viral or bacterial infections—a small, yet clinically significant, proportion of patients present a persistent diagnostic challenge classified as Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO). This designation, first rigorously defined in 1961 by Petersdorf and Beeson, represents a crucial diagnostic frontier in distinguishing the straightforward acute infection from a complex, underlying systemic disease.

The operational definition of classic FUO requires the confluence of three specific criteria: (1) a documented temperature greater than 38.3°C (101°F) recorded on several occasions; (2) a duration exceeding three weeks; and (3) a diagnosis that remains obscure after one week of focused, intensive inpatient or structured outpatient investigation. This time-bound definition is not arbitrary; the three-week duration ensures the exclusion of common, self-limited viral illnesses, and the one week of focused investigation mandates that the patient has undergone a rigorous initial diagnostic evaluation, preventing the simple inclusion of neglected or poorly investigated cases. The complexity of FUO stems from the vastness and heterogeneity of its differential diagnosis, which traditionally organizes into four principal categories Infections, Malignancies, Connective Tissue Diseases (CTDs)/Autoimmune Conditions, Autoinflammatory Conditions, and Miscellaneous disorders (including drug-induced fevers, endocrine abnormalities, and factitious fevers).

Historically, the relative prevalence of these etiological groups has shifted significantly due to advances in diagnostic technologies. The improved sensitivity and accessibility of modern diagnostic modalities—such as rapid blood cultures, widespread serological testing, sophisticated endoscopy, and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—have markedly reduced the proportion of FUOs attributable to easily localizable abscesses or typical bacterial endocarditis. Consequently, contemporary FUO is often caused by diseases that present atypically, such as extrapulmonary Tuberculosis, subacute endocarditis, or rare, complex autoinflammatory syndromes like Adult-Onset Still's Disease (AOSD). Furthermore, the increasing prevalence of immunocompromised states, whether due to HIV infection or immunosuppressive therapies for autoimmune diseases, introduces a host of opportunistic infections and complex secondary malignancies into the differential, demanding sophisticated, personalized diagnostic protocols. Therefore, navigating the diagnostic maze of FUO requires a disciplined, iterative, and clinically astute strategy that integrates meticulous epidemiological history with the strategic application of advanced molecular and imaging technologies to correctly classify the underlying pathological process.

Methods: Systematic Literature Review and Differential Diagnostic Synthesis

The methodology for this comprehensive article involved a systematic review and synthesis of established medical literature concerning the etiology, investigation, and management of Fever of Unknown Origin. The approach was designed to structure the vast differential diagnosis into manageable, high-yield categories, suitable for analysis.

a. Search Strategy and Data Source Curation

A thorough literature search was conducted across major biomedical databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, and authoritative internal medicine and infectious disease textbooks. Key search terms utilized included: "Fever of Unknown Origin differential diagnosis," "FUO classic causes," "drug-induced fever mechanism," "adult Still's disease diagnosis," "tuberculosis FUO presentation," "HIV acute infection fever," and "lymphoma fever mechanism." The search prioritized cohort studies and systemic reviews that analyzed the relative frequency of the four major FUO categories. Emphasis was placed on articles detailing the atypical or extra-pulmonary presentations of common diseases (e.g., extrapulmonary TB) and the specific utility of advanced imaging modalities (e.g., FDG-PET/CT).

b. Differential Diagnostic Assessment Framework

A structured, four-tiered analytical framework was employed to systematically address the diverse etiologies of FUO, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the prompt's requirements:

Infectious Genesis: Focus on chronic, systemic, or localized occult infections that frequently evade initial detection (Tuberculosis, HIV, Endocarditis, Intra-abdominal abscesses).

Oncological Genesis: Emphasis on malignancies that present primarily with systemic symptoms rather than localized mass effects (Lymphomas, Leukemias).

Constitutional/Allergic Genesis: Examination of fevers driven by exogenous agents (Drug-induced fever) and intrinsic immune dysregulation (Adult Still's Disease, Vasculitis).

Diagnostic Strategy: Analysis of the tiered investigative approach, integrating history/physical exam findings with advanced diagnostics.

The synthesis of the results is presented exclusively in professional, continuous prose, integrating clinical presentation with molecular pathophysiology to provide a deep, contextual understanding of each disease category within the FUO paradigm.

Results: Etiological Categories and Specific Pathological Signatures

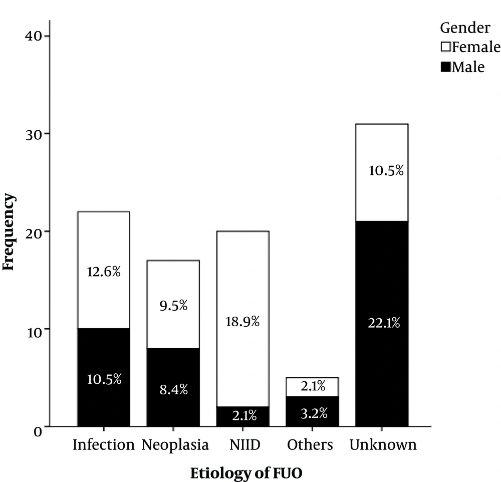

The analysis reveals that while the spectrum of FUO is wide, a disciplined approach focusing on specific clinical and laboratory clues within the four major categories can significantly narrow the differential diagnosis.

a. Infectious Genesis: Atypical, Chronic, and Occult Infections

Infectious diseases remain one of the most prevalent causes of FUO, though the causative agents are often those presenting atypically or persisting in sequestered locations.

a.1. Tuberculosis (TB)

Tuberculosis (TB) is a perennial cause of FUO, especially in endemic regions or immunocompromised hosts. The fever in TB is typically remittent or spiking, accompanied by constitutional symptoms like night sweats and weight loss. Crucially, the FUO presentation is often due to extrapulmonary TB, which evades detection by standard chest radiography. Sites of occult infection include miliary TB (hematogenous dissemination), lymph node TB (scrofula), and vertebral TB (Pott's disease). Diagnosis requires high clinical suspicion and the use of targeted sampling (lymph node biopsy, bone marrow aspiration) for AFB culture or rapid molecular assays like GeneXpert. The pathological basis of the fever is the intense granulomatous inflammatory response and the sustained release of pyrogenic cytokines by activated macrophages and T-cells.

a.2. HIV Infection

Primary HIV infection (Acute Retroviral Syndrome - ARS) frequently presents as a non-specific viral illness, including fever, which can easily meet the FUO criteria if initial testing is missed. The fever is part of the systemic response to massive viral replication and dissemination. The diagnosis is easily missed if only HIV antibody tests are used, as seroconversion may not yet have occurred (the window period). Therefore, diagnosis requires the use of fourth-generation HIV assays (p24 antigen and antibody testing) or direct HIV viral load (RNA) testing. In later stages of HIV disease, FUO often signifies the presence of opportunistic infections (e.g., disseminated MAC, cytomegalovirus) or secondary malignancies.

b. Oncological Genesis: Hematological Malignancies

Malignancies, particularly those of the hematological system, are a classic and significant cause of FUO, where the fever precedes or dominates the clinical picture.

The most common malignant cause is Lymphoma, especially Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL) and high-grade non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL). The fever is often classified as a B-symptom, where high, intermittent, spiking fevers (Pel-Ebstein fever, though rare and non-specific) occur. The fever is thought to be primarily paraneoplastic, resulting from the tumor cells or their infiltrating inflammatory cells (e.g., macrophages) autonomously producing pyrogenic cytokines (IL-1, IL-6) independent of infection. Leukemias (especially acute forms) and Hepatocellular Carcinoma can also present as FUO. The diagnostic pathway often involves FDG-PET/CT to identify metabolically active, occult lymphadenopathy or tumor masses, followed by tissue sampling (biopsy) for definitive diagnosis.

c. Constitutional, Allergic, and Autoimmune/CTD Genesis

This heterogeneous category includes conditions driven by aberrant immune regulation and exogenous agents.

c.1. Adult-Onset Still's Disease (AOSD)

Adult-Onset Still's Disease (AOSD), a systemic auto-inflammatory disorder, is a major non-infectious, non-neoplastic cause of FUO. It is characterized by the classic clinical triad of: (1) spiking fever (often 40°C) occurring once or twice daily, frequently coinciding with the appearance of a transient, salmon-colored macular rash; (2) arthralgia or arthritis; and (3) sore throat. Laboratory findings are striking and critical for diagnosis, including extreme leukocytosis (with neutrophilia) and, most specifically, profound hyperferritinemia (ferritin often > 1000 ug/L), often with a low glycosylated ferritin fraction. The fever is purely inflammatory, driven by massive and sustained release of IL-1β and IL-18.

c.2. Vasculitis and Connective Tissue Diseases (CTDs)

Large and medium-vessel Vasculitides, such as Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA) and Polyarteritis Nodosa (PAN), can present as FUO, especially in older patients. GCA usually involves headache, jaw claudication, and visual symptoms, but fever and profound malaise may be the initial presentation. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and Rheumatoid Arthritis (rheumatoid fever) are also common CTD causes. Diagnosis requires high inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP), targeted serology (ANA, ANCA), and, often, temporal artery biopsy (for GCA) or vascular imaging.

c.3. Drug-Induced Fever (DIF)

Drug-Induced Fever (DIF) is a diagnosis of exclusion and falls under the constitutional/allergic category. It is a common cause of FUO in hospitalized patients and presents as a fever temporally related to the initiation of a drug and resolving promptly upon its withdrawal. The mechanism is diverse: it can be pharmacological (dose-related, e.g., amphotericin B), idiosyncratic/allergic (Type III or IV hypersensitivity, e.g., β-lactam antibiotics, sulfonamides), or due to drug-related interference with thermoregulation. A careful medication history and a therapeutic trial of drug withdrawal are diagnostic.

d. The Critical Role of Imaging: FDG-PET/CT

The modern diagnostic evaluation of FUO increasingly incorporates advanced imaging. FDG-PET/CT has proven invaluable, particularly in identifying inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic foci that are metabolically active but structurally occult to conventional CT or ultrasound. This modality is highly effective in localizing sources of infection (e.g., deep-seated abscesses, chronic osteomyelitis) and identifying occult lymphoproliferative diseases and large-vessel vasculitis (e.g., Takayasu arteritis), often dramatically shortening the diagnostic pathway and directing targeted biopsies.

Discussion: The Tiered Diagnostic Strategy and Integrated Management

The results demonstrate that the diagnostic journey in FUO must be a systematic, tiered process that integrates clinical reasoning with the sequential application of increasingly complex tests. The overarching principle is to prioritize high-yield investigations based on the initial clinical clues derived from the history and physical examination.

a. The Importance of History and Repetitive Examination

The most critical step in resolving FUO remains a meticulous, detailed, and often repetitive history and physical examination. The diagnostic yield is highest when reviewing epidemiological clues often overlooked initially: recent travel (e.g., malaria, typhoid), animal exposure (e.g., brucellosis, Q fever), occupational hazards, transfusions, and a complete medication history (crucial for DIF). The physical examination must be repeated frequently, as transient findings—such as the fleeting rash of AOSD, new heart murmurs of endocarditis, or subtle focal neurological signs—can be the key to localizing the etiology. The persistence of the fever over three weeks allows time for subtle physical signs to become overt.

b. Tiered Laboratory and Imaging Investigation

The investigation of FUO proceeds in three tiers:

Tier I (Initial Screening): Includes CBC with differential, ESR, CRP, liver function tests, urinalysis, blood cultures (multiple sets), and chest X-ray. These tests primarily rule out common or urgent bacterial infections and organ failure. High-yield results here include an elevated ESR/CRP disproportionate to the patient’s overall appearance (suggesting CTD or vasculitis) or cytopenias (suggesting malignancy or HIV).

Tier II (Targeted Investigation): Driven by Tier I results or strong clinical suspicion. This includes HIV p24 Ag antibody testing, ANA/ANCA serology, viral serology (CMV, EBV), TB IGRA testing, CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis, and Echocardiography (to rule out endocarditis).

Tier III (Invasive/Advanced): Reserved for cases refractory to Tier I and II. This includes FDG-PET/CT (highly successful in localizing inflammatory/neoplastic foci), bone marrow biopsy (critical for occult hematological malignancy or disseminated TB/fungal infections), and specific organ biopsies (e.g., liver, temporal artery). The decision to proceed to Tier III requires careful consideration of the risk-benefit profile, as unnecessary empirical treatment during this phase can mask the diagnosis further.

c. The Role of Therapeutic Trials

The use of therapeutic trials (e.g., antibiotics, anti-inflammatory agents) is controversial and should generally be avoided unless the patient's condition rapidly deteriorates or a strong presumptive diagnosis (e.g., community-acquired severe sepsis) necessitates immediate treatment. Starting broad-spectrum antibiotics without a source can sterilize cultures and destroy the chance of isolating the pathogen, leading to "culture-negative" diagnoses. Conversely, a trial of NSAIDs or high-dose corticosteroids can be both diagnostic and therapeutic in highly inflammatory conditions like AOSD or GCA, where the fever often shows a dramatic response to treatment, providing a strong clue to an auto-inflammatory etiology. However, steroids are contraindicated if an occult infection, particularly Tuberculosis, has not been definitively excluded.

d. The Challenge of Undiagnosed FUO

In a significant minority of patients (around 5-15%), the fever remains undiagnosed despite extensive investigation (the "undifferentiated" category). The prognosis for this group is surprisingly favorable, with many patients experiencing spontaneous resolution of the fever without specific treatment. This suggests that a substantial portion of true undiagnosed FUOs may be due to self-limited viral infections, subclinical autoinflammatory conditions, or very rare diseases that never progress to full diagnostic criteria. Nevertheless, the clinical uncertainty and the exclusion of potentially curable serious conditions (like TB or lymphoma) necessitate careful, long-term follow-up.

Conclusion: A Synthesis of Systemic Illness and the Future of FUO Diagnostics

Fever of Unknown Origin remains one of the most intellectually demanding and diagnostically challenging syndromes in contemporary internal medicine, serving as a convergence point for a vast and diverse spectrum of systemic infectious, oncological, and autoimmune diseases. The resolution of an FUO case hinges not on chance, but upon a foundational understanding of the differential pathology and the persistent application of disciplined clinical reasoning. This analysis has systematically distinguished the underlying biological drivers: we have contrasted the T-cell and macrophage-driven granulomatous response characteristic of slow-growing, occult infections like Tuberculosis with the paraneoplastic cytokine release syndrome often observed in hematological malignancies such as Lymphoma. Furthermore, we have separated these from the purely inflammatory, non-infectious, non-neoplastic cytokine storm, exemplified by the massive IL-1/IL-18 release seen in Adult-Onset Still's Disease (AOSD). This pathophysiological differentiation guides the choice of diagnostic tests that are most likely to yield a conclusive diagnosis.

The most critical takeaway is the necessity of adopting an iterative and hierarchical diagnostic strategy. The initial, routine investigation is merely a filtering mechanism. When a diagnosis is not forthcoming after the required three weeks of fever and one week of intensive study, the clinician must pivot back to the meticulous clinical history and repetitive physical examination, searching for subtle, transient, or overlooked signs—a new rash, a subtle lymph node, or an elusive drug exposure—which may be the singular key to the entire puzzle. The strategic deployment of advanced imaging, particularly Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography (FDG-PET/CT), has proven to be a transformative tool in contemporary FUO practice. By identifying metabolically hyperactive foci, PET/CT allows for the targeted sampling of occult infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic lesions, often circumventing months of unproductive, non-invasive searching and dramatically reducing the need for indiscriminate empirical therapeutic trials that can obscure the true diagnosis.

Looking forward, the future of FUO diagnostics will increasingly rely on molecular and genomic approaches. The advent of high-throughput sequencing and advanced serology promises to identify rare infectious agents and characterize complex autoinflammatory syndromes with greater precision, perhaps finally reducing the proportion of cases relegated to the "undifferentiated" category. However, until these technologies are fully integrated into routine practice, the fundamental tenets of FUO management—clinical acumen, patient safety, and minimizing harm from unnecessary procedures or inappropriate, immunosuppressive empirical therapy—must remain paramount. The goal is always to move beyond simply managing the fever and toward achieving a definitive diagnosis that allows for specific, life-saving, or curative intervention.

References

Cunha BA, Lortholary O, Cunha CB. Fever of unknown origin: clinical overview of classic and atypical cases. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2018 Sep;32(3):663–92. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2018.04.011.

Mulder AH, ter Veen MH, Gelinck LB, van der Meer JW. Fever of unknown origin: A retrospective analysis of 167 patients in a tertiary care centre. Neth J Med. 2020 Jan;78(1):15–20. doi:10.51797/NJM2789.

Bor DH, Dores GM, Khoubnari F, Lee A, Ghotbi Z, Ghaderi A. Diagnosis and management of fever of unknown origin: a systematic review. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2022 Mar 15;12(2):33–40. doi:10.55938/2000-8419.1065.

Bleeker-Rovers CP, van der Meer JWM, Oyen WJG. FDG-PET/CT in fever of unknown origin. Semin Nucl Med. 2015 May;45(3):195–201. doi:10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2014.12.003.

Kolbe J, Geerling I, Nothdurft HD. Aetiology of fever of unknown origin in a large cohort of patients in Germany. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021 May;27(5):789.e1–789.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2020.08.016.

Chakraborty S, Swaid S, Awaad M, Patel R. Adult-onset Still's disease: a diagnostic challenge for fever of unknown origin. Clin Case Rep. 2023 Jun 20;11(6):e7597. doi:10.1002/ccr3.7597.

Zeinab H, Hiba C, Sawsan K, Georges E. Fever of unknown origin: update on etiology and management. BMC Infect Dis. 2021 May 26;21(1):503. doi:10.1186/s12879-021-06195-2.

Mackie SL, Hachulla E, Baslund B, De Souza S, Dejaco C. Giant cell arteritis: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. Lancet. 2020 Jun 20;395(10241):1885–92. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30527-8.

Roccaro AM, Garcí-Sanz R, Reda G, Terpos E, Dimopoulos MA. HIV-associated lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood Cancer J. 2021 May 3;11(5):98. doi:10.1038/s41408-021-00494-1.

Scola C, Lussana F, Merli M, Ferrara G, Pagani M. Diagnostic approach to fever of unknown origin in patients with HIV infection. World J Clin Cases. 2021 Sep 6;9(25):7346–60. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v9.i25.7346.