Acute Post Hemorrhagic Anemia

1. Samatbek Turdaliev

2. Sonal Saini

Ishwari Satalkar

(1. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic

2. Students, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.)

Abstract

Acute Post-Hemorrhagic Anemia (APHA) represents a critical, life-threatening condition resulting from rapid blood loss, typically defined as the loss of circulating blood volume exceeding 15% to 20% within a short time frame. Unlike chronic anemias, the immediate threat posed by APHA is not primarily the reduction in oxygen-carrying capacity (anemia), but rather hypovolemia and resultant hypovolemic shock, which leads to systemic tissue hypoperfusion and metabolic derangement. This article provides a comprehensive analysis, detailing the complex physiological compensatory mechanisms activated following acute hemorrhage, the sequential hematological changes that define the diagnostic timeline, and the critical principles governing resuscitation and definitive hemostasis. A rigorous focus is placed on the differential mechanisms of compensation (fluid shift versus erythropoiesis) and the dynamic evolution of hematological indices, emphasizing that the initial absence of overt anemia can be misleading. Understanding the transition from hypovolemic shock to established anemia is paramount for timely, appropriate intervention, which involves rapid volume restoration, permissive hypotension, and the strategic use of blood products within a Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) framework to minimize mortality and morbidity in trauma and surgical settings.

1. Introduction: The Criticality of Volume Loss in Acute Hemorrhage

Acute Post-Hemorrhagic Anemia (APHA) is a time-sensitive clinical syndrome triggered by rapid and significant depletion of the circulating blood volume. While the term "anemia" implies a deficiency in red blood cell (RBC) mass or hemoglobin concentration, the immediate, life-threatening consequence of acute hemorrhage is the precipitous drop in mean systemic filling pressure and subsequent reduction in cardiac output, leading directly to hypovolemic shock. The pathophysiology of APHA is distinct from chronic anemias, where the slow progression allows for robust physiological adaptation, primarily through increased erythropoiesis and chronic shifts in the oxygen dissociation curve. In APHA, the body's response is an immediate, multi-system effort focused on maintaining perfusion to vital organs—a triage of blood flow.

The magnitude of blood loss is clinically classified by the American College of Surgeons (ATLS guidelines), correlating the percentage of lost volume with the severity of shock, ranging from Class I (less than 15% loss, minimal symptoms) to Class IV (greater than 40% loss, immediate threat to life). The clinical course of APHA involves two distinct phases: the immediate hypovolemic phase and the delayed hemodilution phase. In the immediate phase, compensatory vasoconstriction masks the true volume deficit. The subsequent compensatory shift of interstitial fluid into the vascular space—a process known as hemodilution—is what eventually causes the measurable fall in hemoglobin and hematocrit, thus revealing the anemia. Consequently, the initial hematological values can be deceptively normal, a crucial trap in acute care diagnosis.

This article aims to dissect the pathophysiology of APHA, focusing on the dynamic changes in fluid dynamics and hematological indices. We will detail the sequential steps of diagnosis, from clinical assessment of shock to interpretation of laboratory data over time. Finally, we will outline the principles of modern, evidence-based management, particularly the shift towards a coordinated transfusion protocol known as Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR).

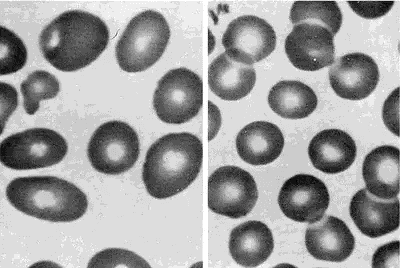

Peripheral blood smears from a patient with megaloblastic anemia (left) and from a normal subject (right), both at the same magnification. The smear from the patient shows variation in the size and shape of erythrocytes and the presence of macro-ovalocytes. From Goldman and Bennett, 2000.

2. Methods: Synthesis of Physiological Response and Management Protocols

The methodological approach for this article involved a rigorous, systematic review and synthesis of established literature focusing on critical care, trauma surgery, transfusion medicine, and cardiovascular physiology. The objective was to create an integrated understanding of the acute physiological response to hemorrhage and the protocols governing effective management.

2.1. Literature Search Strategy and Source Curation

The literature search was executed across major biomedical databases, including PubMed, Cochrane Library, and critical care guidelines published by organizations such as the American College of Surgeons (ATLS), the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), and the AABB (formerly American Association of Blood Banks). Key search terms utilized included: "acute post-hemorrhagic anemia pathophysiology," "hemodilution kinetics acute hemorrhage," "damage control resuscitation principles," "transfusion massive hemorrhage protocol," and "physiological compensation to hypovolemic shock." The review prioritized clinical studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and consensus guidelines published within the last decade to ensure the inclusion of contemporary practices, particularly those involving ratio-based and goal-directed resuscitation.

2.2. Physiological and Therapeutic Assessment Framework

A structured analytical framework was employed to organize the complexities of APHA into sequential, manageable phases:

1. Phase I: Compensatory Mechanisms: Analysis of immediate autonomic and humoral responses to volume loss (vasoconstriction, tachycardia, fluid shifts).

2. Phase II: Hematological Evolution: Detailed examination of the time-dependent changes in hemoglobin and hematocrit due to hemodilution, differentiating true blood loss from laboratory evidence of anemia.

3. Phase III: Diagnostic Assessment: Correlation of clinical signs of shock (e.g., lactate, base deficit) with hematological indices.

4. Phase IV: Management Principles: Comparison of conventional crystalloid-heavy resuscitation with modern DCR strategies involving balanced blood product transfusion.

3. Results: The Dynamic Physiological and Hematological Cascade

The review elucidates a predictable yet complex physiological cascade that follows acute hemorrhage, defining the time course of APHA and dictating the critical window for intervention.

3.1. Phase I: Autonomic and Humoral Compensation to Hypovolemia

The immediate response to acute blood volume loss is dominated by the autonomic nervous system and the humoral cascade, aiming to restore cardiac output and preserve mean arterial pressure (MAP). The rapid decrease in central venous pressure and arterial pressure is detected by baroreceptors in the aortic arch and carotid bodies. This triggers a massive, instantaneous sympathetic outflow mediated by norepinephrine and epinephrine. The resulting systemic vasoconstriction significantly increases systemic vascular resistance (SVR), particularly in non-vital capillary beds (skin, muscle, viscera), effectively shunting blood towards the heart and brain. Concurrently, increased contractility and tachycardia attempt to maintain cardiac output (CO = HR/SV).

The humoral response further reinforces volume retention. Reduced renal perfusion activates the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS), leading to increased Angiotensin II (a potent vasoconstrictor) and Aldosterone (promoting renal Na+ and water retention). The posterior pituitary releases Arginine Vasopressin (AVP or ADH), a powerful antidiuretic and vasopressor, in response to rising plasma osmolality and falling MAP. These mechanisms collectively stabilize blood pressure, often successfully masking the severity of Class I and early Class II hemorrhage.

3.2. Phase II: The Kinetics of Hemodilution and Overt Anemia

The most critical aspect of APHA pathophysiology is the time delay between actual blood loss and the laboratory detection of anemia. The initial Hb and Hct readings immediately following hemorrhage can be normal because both the circulating red cell mass and the plasma volume are reduced proportionally.

The onset of overt anemia is driven by the transcapillary refill mechanism. In response to the fall in capillary hydrostatic pressure (Pc) and the maintenance of plasma colloid osmotic pressure, the Starling forces shift significantly, favoring the passive movement of protein-free interstitial fluid into the vascular space. This process, initiated within minutes and peaking over the subsequent 24 to 72 hours, is the body’s attempt at internal volume replacement. This massive influx of interstitial fluid effectively dilutes the remaining concentrated RBC mass. Consequently, the measured hemoglobin concentration and hematocrit drop progressively, eventually reflecting the actual deficit in RBC mass relative to the expanded plasma volume. This hemodilution phenomenon makes serial Hb/Hct measurements crucial for accurate diagnosis and monitoring.

3.3. Phase III: Hematological and Erythropoietic Response

Beyond the immediate fluid shift, the definitive hematological response involves increased erythropoiesis. Acute tissue hypoxia stimulates the kidneys to rapidly increase the synthesis and release of Erythropoietin (EPO). However, since mature RBCs require several days to be produced and released from the bone marrow, the impact of this EPO surge is not clinically evident until 3 to 7 days after the acute event, typically observed as a rise in the reticulocyte count. The initial peripheral blood smear often shows normocytic, normochromic RBCs, consistent with a rapid loss of normal cells, distinguishing APHA from microcytic or macrocytic chronic anemias.

3.4. Clinical and Biochemical Markers of Shock

While the Hb may be stable initially, the true severity of hypoperfusion is best assessed by markers of metabolic derangement. The shunting of blood flow away from non-vital organs leads to localized tissue hypoxia and a shift toward anaerobic metabolism. This is reflected by an acute and often profound rise in serum lactate and an increase in base deficit (reflecting unbuffered acid accumulation). Elevated lactate and a deep base deficit serve as highly sensitive, early markers of inadequate tissue perfusion, providing a more immediate and reliable measure of shock severity than initial Hb or Hct values.

4. Discussion: Diagnosis, Resuscitation Strategy, and Therapeutic Evolution

The pathophysiology of APHA mandates a shift in the diagnostic paradigm, prioritizing clinical signs of shock over initial laboratory hematology, and requires a highly specific, rapidly deployable therapeutic strategy.

4.1. The Diagnostic Challenge: Interpreting Deception

The most significant diagnostic challenge in APHA is the hemodilution lag. Clinicians must recognize that a stable or only minimally reduced Hb/Hct in the setting of ongoing or significant recent hemorrhage does not rule out massive blood loss. Diagnosis hinges on the simultaneous assessment of the ATLS Class of Shock (based on heart rate, blood pressure, pulse pressure, mental status, and urine output) and the biochemical markers of hypoperfusion (lactate and base deficit). A patient exhibiting tachycardia, poor peripheral perfusion, and metabolic acidosis should be presumed to have severe, ongoing hemorrhage requiring aggressive intervention, irrespective of a normal initial Hb. Serial measurements, ideally repeated every 30 to 60 minutes in the acute phase, are essential to track the expected fall in hematocrit as hemodilution progresses.

4.2. Evolution of Resuscitation: From Crystalloids to Damage Control

Historically, the initial management of APHA involved aggressive volume replacement primarily using large volumes of crystalloid fluids. This practice, however, proved detrimental, leading to the "lethal triad" of acidosis, hypothermia, and coagulopathy. Excessive crystalloid use exacerbates APHA by: (1) accelerating hemodilution, thereby lowering Hb and O2 delivery; (2) inducing coagulopathy by diluting clotting factors; and (3) worsening hypothermia and metabolic acidosis.

Modern trauma and surgical critical care has shifted decisively towards Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR). DCR principles prioritize:

1. Permissive Hypotension: Maintaining a lower target MAP (e.g., systolic BP of 80-100 mmHg) in non-head injured patients to prevent clot disruption until surgical control of bleeding is achieved.

2. Hemostatic Resuscitation: Rapid, balanced transfusion of blood products in high ratios, typically approximating the physiological ratio: 1 unit of packed RBCs : 1 unit of Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP) : 1 platelet apheresis unit. This approach simultaneously replaces oxygen-carrying capacity and clotting factors, addressing the traumatic coagulopathy induced by hemorrhage itself. The rapid initiation of a Massive Transfusion Protocol (MTP) is the core of DCR.

4.3. Coagulopathy: The Vicious Cycle

The interplay between hemorrhage and coagulopathy is a devastating feedback loop. Acute blood loss causes not only factor dilution (from resuscitation) but also an endogenous trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC) mediated by shock, hypothermia, and acidosis. Acidosis directly impairs the function of clotting factors and platelets. Hypothermia impairs enzyme kinetics and platelet aggregation. Therefore, effective management of APHA requires aggressive measures to prevent and treat hypothermia (warming blankets, warm fluid administration) and rapid correction of metabolic acidosis alongside the balanced transfusion of blood products. The strategic use of procoagulant agents, such as Tranexamic Acid (TXA), a synthetic lysine analogue that inhibits fibrinolysis, has become standard practice in the early management of significant trauma-related hemorrhage.

4.4. Long-Term Recovery and Iron Status

Once definitive hemostasis is achieved and the acute crisis is resolved, the patient enters the recovery phase. The compensatory erythropoiesis, initiated by the EPO surge, gradually resolves the anemia over several weeks. However, because the hemorrhage entails a massive loss of total body iron (locked within the lost RBCs), the patient often develops a delayed absolute iron deficiency. This secondary iron deficiency can limit the maximum rate of RBC regeneration. Therefore, long-term management requires assessing iron status (ferritin, transferrin saturation) and providing supplemental oral or intravenous iron therapy to maximize the speed and efficacy of bone marrow recovery.

5. Conclusion

Acute Post-Hemorrhagic Anemia is a critical, dynamic syndrome where the initial, overwhelming threat is hypovolemic shock, not merely low hemoglobin. The defining characteristics of APHA are the powerful, temporary autonomic compensatory mechanisms and the time-dependent hemodilution lag that causes a delayed and deceptive fall in hematological indices. Clinically, diagnosis must therefore rely on serial assessment of shock parameters (heart rate, perfusion status, and metabolic markers like lactate and base deficit) rather than a single initial Hb value. The therapeutic evolution has moved away from crystalloid-heavy resuscitation toward a paradigm of Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR), utilizing ratio-based, balanced transfusion of blood products (RBCs, FFP, platelets) and early administration of antifibrinolytics like TXA. Successful management requires immediate hemostasis, rapid correction of the lethal triad of hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy, and subsequent identification and treatment of the inevitable post-hemorrhagic iron deficiency to facilitate complete hematological recovery. A unified, multidisciplinary trauma or massive hemorrhage protocol is the standard of care for optimizing survival and minimizing the long-term morbidity associated with acute severe blood loss.

References

Cannon JW. Hemorrhagic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 12;378(15):1442–51.

Moore HB, Moore EE, Neal MD, Reisner AT, Schuster KM, Schöchl H, et al. Massive Transfusion in Trauma: The Role of Blood Component Ratios and Resuscitation Strategy. J Am Coll Surg. 2017 May;224(5):894–906.

Rossaint R, Bouillon B, Cerny V, Coats TJ, Duranteau D, Fernández-Mondéjar E, et al. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: fourth edition. Crit Care. 2016 Apr 28;20(1):100.

Kizilbash AM, Bies R. Acute Anemia. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

Guyette FX, Brown JB, Zenati MS, Early B, Adams PW, Martin-Gill C, et al. Prehospital Whole-Blood Transfusion for Traumatic Hemorrhagic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jul 28;387(3):234–44.

Spahn DR, Bouillon B, Cerny V, Duranteau J, Filipescu D, Hunt BJ, et al. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: fifth edition. Crit Care. 2019 Mar 19;23(1):98.

Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Davenport RA. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: pathophysiology and general management. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017 Dec;23(6):467–71.

Holcomb JB, Tilley BC, Rivera-Marcano L, Zarzabal LA, Johnson B, Kauvar DS, et al. Transfusion of Plasma, Platelets, and Red Blood Cells in a 1:1:1 Ratio in the Massive Transfusion Protocol: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2017 Jun 13;317(22):2311–21.

Shanks D, Singh R. Haemodilution and the Post-Hemorrhage Anemia Lag: Pathophysiological Implications for Diagnosis. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2021 Jul-Sep;14(3):145–50.

O’Shaughnessy DF, Gardner K, Miles B. The role of intravenous iron in the treatment of post-hemorrhagic anemia. Transfusion. 2020 Jan;60(1):210–20.