Acute Post hemorrhagic Anemia

1. Samatbek Turdaliev

2. Ramesh Chouhan

Aneetta Uthaman

(1. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic

2. Students, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.)

Abstract

Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia (APHA), categorized under the ICD-10 code D62, constitutes a critical hematological and hemodynamic emergency resulting from the rapid, high-volume loss of intravascular blood. Unlike chronic anemia, where physiological compensation occurs over an extended timeline, APHA precipitates immediate hypovolemia and tissue hypoxia, frequently progressing to hemorrhagic shock and multi-organ failure if not promptly intercepted. This report provides an exhaustive examination of APHA, synthesizing current literature to elucidate the complex interplay between acute volume depletion, neurohormonal compensation, and the delayed hematological manifestation of anemia known as the "hematocrit lag". It critically evaluates the shifting paradigms in resuscitation, specifically the transition from crystalloid-heavy regimens to Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) utilizing balanced blood product ratios (1:1:1) and antifibrinolytic adjuncts like Tranexamic Acid (TXA).

Furthermore, the report details the complications associated with massive transfusion, such as Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury (TRALI) and Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload (TACO), and reviews post-stabilization strategies for hemoglobin recovery, including the comparative efficacy of intravenous versus oral iron therapies in the context of inflammation-induced hepcidin blockade.

Keywords: Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia, Hemorrhagic Shock, Hematocrit Lag, Damage Control Resuscitation, Massive Transfusion Protocol, Tranexamic Acid, Lactate Clearance, TRALI, TACO, Hepcidin.

1. Introduction

Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia (APHA) represents a distinct clinical entity defined by a precipitous decline in red blood cell (RBC) mass and hemoglobin concentration following sudden, severe hemorrhage. While anemia is universally defined by hemoglobin thresholds-typically less than 13.5 g/dL in men and 12.0 g/dL in women-the pathophysiology of APHA is fundamentally different from chronic etiologies such as nutritional deficiencies or bone marrow failure. In chronic anemia, the gradual onset allows for significant hemodynamic compensation, including 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG) mediated shifts in the oxygen dissociation curve and increased cardiac output, often rendering patients asymptomatic even at very low hemoglobin levels. Conversely, APHA is characterized by an acute failure of oxygen delivery (DO2) to meet metabolic demand (VO_2) due to the simultaneous loss of oxygen-carrying capacity and circulating volume.

The clinical presentation of APHA is biphasic and often deceptive. The initial phase is dominated by hypovolemia rather than anemia per se; the loss of whole blood implies that the concentration of hemoglobin within the remaining blood volume remains initially unchanged. It is only after the recruitment of interstitial fluid or the administration of exogenous fluids that hemodilution occurs, unmasking the anemia. This diagnostic latency poses a significant risk for underestimation of blood loss in the acute setting.

The mortality associated with APHA is high and is primarily driven by the sequelae of hemorrhagic shock, including the "lethal diamond" of trauma: coagulopathy, acidosis, hypothermia, and hypocalcemia. Consequently, the management of APHA has evolved from a focus on restoring normal vital signs with crystalloids to a strategy of "hemostatic resuscitation," which prioritizes the preservation of coagulation factors, the maintenance of tissue perfusion pressure, and the early correction of oxygen debt.

2. Etiology and Classification of Acute Hemorrhage

The etiologies of APHA are diverse, encompassing traumatic, surgical, obstetric, and spontaneous hemorrhagic events. Understanding the source of bleeding is critical for risk stratification and surgical intervention.

2.1 Traumatic Etiologies

Trauma remains the leading cause of APHA in emergency departments globally. The rapidity of exsanguination is dictated by the vascular territory involved and the integrity of surrounding compartments.

• Arterial vs. Venous Hemorrhage: Arterial hemorrhage, characterized by pulsatile, high-pressure flow, leads to the most rapid volume depletion. Common scenarios include transection of the femoral or brachial arteries or traumatic aortic injury. Although lower in pressure, venous hemorrhage can be catastrophic, particularly in the context of pelvic fractures where the disruption of the presacral venous plexus occurs in a retroperitoneal space that can accommodate several liters of blood before tamponade occurs.

• Compartmental Storage: A crucial concept in trauma is the "silent" accumulation of blood. The thigh can sequester 1 to 2 liters of blood following a femoral fracture with minimal external deformity. Similarly, the retroperitoneum and thoracic cavity can hold massive volumes, leading to Class III or IV shock without external bleeding.

2.2 Non-Traumatic and Internal Hemorrhage

Non-traumatic causes are frequently occult, requiring a high index of suspicion and rapid diagnostic imaging.

• Gastrointestinal (GI) Bleeding: Acute upper GI bleeding (e.g., peptic ulcer disease, Mallory-Weiss tears) and lower GI bleeding (e.g., diverticulosis) are common causes of APHA. Esophageal varices, a consequence of portal hypertension in cirrhosis, present a unique challenge due to the concomitant coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia often present in these patients, leading to rapid, high-volume blood loss.

• Vascular Ruptures: The rupture of an Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) is a catastrophic event with high immediate mortality. The sheer volume of blood lost into the retroperitoneum can lead to immediate cardiovascular collapse. Similarly, cerebral aneurysms, while involving smaller volumes, can cause significant morbidity and secondary ischemic injury.

• Obstetric Hemorrhage: Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is a leading cause of maternal mortality. While traditionally defined as >500 mL of blood loss, massive PPH can involve the loss of the entire blood volume within minutes. Causes include uterine atony, retained placenta, and genital tract trauma. Ectopic pregnancy rupture represents a surgical emergency where internal bleeding typically exceeds vaginal bleeding.

• Iatrogenic Causes: Major surgical procedures, particularly orthopedic (hip/knee arthroplasty) and cardiac surgeries, are significant causes of APHA. The "Post-operative Anemia" phenotype is distinct, often complicated by the inflammatory stress response which hinders recovery.

2.3 Coagulopathic Bleeding

Patients with congenital bleeding disorders (e.g., hemophilia, von Willebrand disease) or those on anticoagulants (warfarin, direct oral anticoagulants) are at high risk for APHA from minor insults. In these patients, the primary pathology is the inability to form a stable clot, leading to prolonged, high-volume bleeding. Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC), characterized by the widespread activation of coagulation and subsequent consumption of clotting factors, can lead to uncontrolled hemorrhage and APHA in septic or traumatized patients.

3. Pathophysiology: From Hemorrhage to Shock

The transition from blood loss to APHA and shock involves a complex sequence of hemodynamic, fluid, and metabolic shifts.

3.1 Neurohormonal Response and Hemodynamics

The body's immediate response to hemorrhage is mediated by the autonomic nervous system. Baroreceptors in the aortic arch and carotid sinus detect the drop in mean arterial pressure (MAP) and pulse pressure, triggering a massive sympathetic discharge.

• Catecholamine Surge: The release of epinephrine and norepinephrine causes intense peripheral vasoconstriction, shunting blood away from the skin, gut, and kidneys to preserve perfusion to the heart and brain. This manifests clinically as pallor and cool extremities.

• Hemodynamic Compensation:

• Heart Rate: Increases to maintain cardiac output (CO = HR x Stroke Volume).

• Contractility: Increases to maximize ejection fraction.

• Venous Tone: Venoconstriction mobilizes blood from venous capacitance vessels (the "venous reservoir"), effectively performing an "autotransfusion" of up to 1 liter of blood.

• Pulse Pressure: A narrowing pulse pressure (the difference between systolic and diastolic pressure) is one of the earliest signs of volume loss. As diastolic pressure rises due to vasoconstriction while systolic pressure remains constant or falls, the pulse pressure narrows.

3.2 The Hematocrit Lag Phenomenon: A Diagnostic Pitfall

A critical pathophysiological feature of APHA is the delay in the drop of hemoglobin and hematocrit (Hct). This phenomenon, often termed "hematocrit lag," is a frequent source of clinical error.

When acute hemorrhage occurs, whole blood is lost. The remaining intravascular fluid contains the same concentration of RBCs as the lost fluid. Therefore, if a complete blood count (CBC) is drawn immediately after a massive hemorrhage, the Hb and Hct may appear entirely normal. The reduction in Hct values is a secondary process dependent on the dilution of the remaining RBC mass by fluid entering the intravascular space.

This dilution occurs via two primary mechanisms:

1. Transcapillary Refill (Physiologic): In response to hypovolemia, Starling forces at the capillary level shift. The drop in capillary hydrostatic pressure allows interstitial fluid to move into the vascular compartment. This "autotransfusion" of protein-poor, cell-free fluid dilutes the plasma. Studies indicate this process begins within minutes but is slow; only 20-50% of the lost volume is replaced by interstitial fluid within the first hour. Full equilibration can take 24 to 72 hours.

2. Iatrogenic Hemodilution: The administration of crystalloid resuscitation fluids (e.g., Normal Saline, Lactated Ringer's) rapidly dilutes the blood. This explains why Hct drops precipitously after resuscitation begins.

Consequently, a "normal" hematocrit in a trauma patient does not rule out significant blood loss, and clinical decisions must be based on physiological parameters (heart rate, blood pressure, lactate) rather than initial Hb levels.

3.3 Metabolic Derangement: The Shift to Anaerobiosis

As perfusion fails, oxygen delivery (DO_2) falls below the critical threshold required for aerobic metabolism. Cells switch to anaerobic glycolysis, an inefficient pathway that produces only 2 ATP molecules per glucose molecule (compared to 36 ATP in aerobic respiration) and generates lactic acid as a byproduct.

• Lactic Acidosis: Serum lactate accumulation is a direct marker of tissue hypoxia. Elevated lactate (>2-4 mmol/L) correlates strongly with mortality. The ability to clear lactate ("Lactate Clearance") within the first 12-24 hours of resuscitation is a powerful prognostic indicator; failure to clear lactate predicts multi-organ failure and death.

• Base Deficit: The accumulation of metabolic acids consumes bicarbonate buffers, resulting in a base deficit. A base deficit more negative than 6 mmol/L indicates severe shock and significant oxygen debt.

3.4 Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy (TIC) and the Lethal Diamond

Severe hemorrhage frequently induces a specific coagulopathy distinct from DIC. This is driven by the "Lethal Diamond" of trauma resuscitation.

1. Hypothermia: Exposure and the administration of cold fluids inhibit the enzymatic reactions of the coagulation cascade.

2. Acidosis: Metabolic acidosis (pH < 7.2) physically alters the structure of coagulation factors and impairs thrombin generation.

3. Coagulopathy: The consumption of factors and platelets, combined with the activation of the Protein C pathway, leads to a hypocoagulable and hyperfibrinolytic state.

4. Hypocalcemia: Calcium is a vital cofactor for the coagulation cascade (specifically Factor IV). Massive transfusion of citrated blood products (which chelate calcium) leads to severe hypocalcemia, further inhibiting clotting and depressing myocardial contractility.

4. Clinical Presentation and Classification

The clinical presentation of APHA correlates with the volume of blood lost. The American College of Surgeons Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines provide a structured classification system, though it is important to note these are based on a 70 kg healthy male and may vary in elderly or pediatric populations.

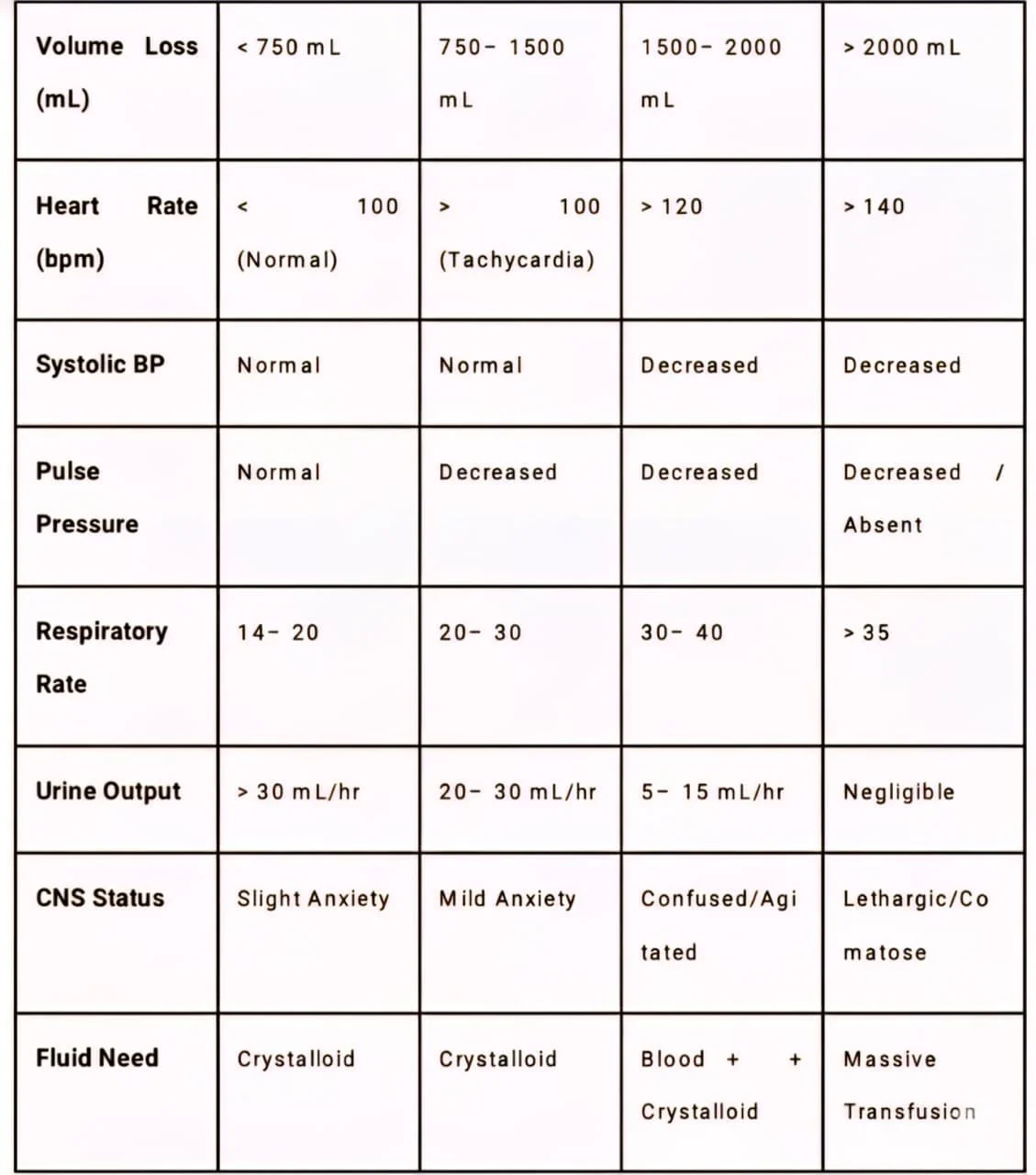

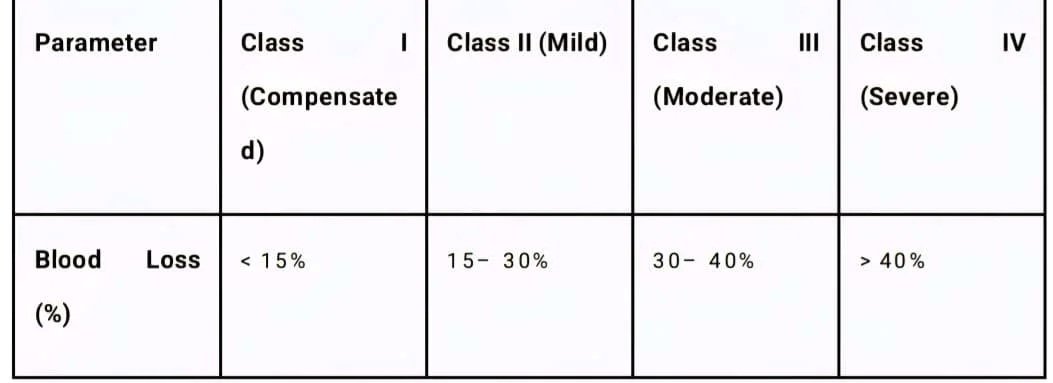

4.1 ATLS Classification of Hemorrhage

Table 1: ATLS Hemorrhagic Shock Classification

Detailed Analysis of Classes:

• Class I: Often asymptomatic. Physiological reserves compensate fully. Equivalent to blood donation.

• Class II: The hallmark is tachycardia and narrowed pulse pressure. Systolic pressure is maintained by catecholamines. This is the stage of "compensated shock." Anxiety is common due to CNS stimulation.

• Class III: Compensatory mechanisms fail. Hypotension develops. This is the critical transition point where perfusion to vital organs is threatened. Blood transfusion is typically required.

• Class IV: Premorbid state. The patient is often unconscious, skin is ashen, and pulse may be thready or non-palpable. Immediate exsanguination protocol is required to prevent cardiac arrest.

4.2 Limitations of Classification

Clinicians must recognize that "normal" vital signs can be misleading.

• Bradycardia: Paradoxical bradycardia can occur in up to 30% of hypotensive trauma patients due to vagal stimulation (Bezold-Jarisch reflex).

• Medications: Beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers can blunt the tachycardic response, masking Class II/III shock.

• Age: Elderly patients have reduced cardiovascular reserve and may decompensate with less volume loss, while pediatric patients maintain blood pressure until a sudden, catastrophic collapse.

5. Diagnostic Evaluation

Diagnosis relies on a multimodal approach integrating physical exam, biomarkers, and imaging.

5.1 Laboratory Biomarkers

• Complete Blood Count (CBC):

• Hb/Hct: As discussed, initial values may be normal. Serial measurements q4h or q6h are essential to track the "unmasking" of anemia. A hemoglobin < 10 g/dL in the first 30 minutes is a strong predictor of the need for massive transfusion.

• Platelets: Thrombocytopenia may develop due to consumption and dilution.

• WBC: A "stress leukocytosis" with a left shift is common immediately post-hemorrhage due to demargination of neutrophils driven by cortisol and catecholamines.

• Shock Biomarkers:

• Lactate: Sensitivity > Specificity. A lactate > 4.0 mmol/L requires immediate resuscitation. The trend of lactate (clearance) is more useful than a single value.

• Base deficit: Obtained via Arterial Blood Gas (ABG). A base deficit > -6 correlates with Class III shock and the need for blood products.

• Coagulation Panel:

• Fribrinogen: Often the first factor to deplete. Levels < 100 mg/dL necessitate cryoprecipitate transfusion.

• INT/ PTT: Prolongation indicates consumption of factors and TIC.

5.2 Hematology and Peripheral Smear

The bone marrow response to acute hemorrhage is delayed.

• Reticulocyte Count: In the immediate phase (0-48 hours), the reticulocyte count is typically normal because the marrow has not yet ramped up production. Erythroid hyperplasia and the release of reticulocytes typically begin at day 3 and peak at day 7. Therefore, a regenerative anemia (elevated reticulocyte count) is a retrospective sign of hemorrhage or hemolysis.

• Peripheral Smear Morphology:

• Acute phase: Cells are usually normocytic and normochromic.

• Recovery phase: As reticulocytes are released, polychromasia (bluish tint to large RBCs) becomes evident.

• Specific findings: Schistocytes may indicate DIC or mechanical hemolysis; spherocytes may suggest immune-mediated destruction rather than simple hemorrhage.

5.3 Imaging Modalities

• FAST Exam (Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma): A bedside ultrasound protocol used to identify free fluid in the pericardium, peri-hepatic, peri-splenic, and pelvic spaces. It is the first-line screening tool for unstable patients.

• CT Angiography: The gold standard for stable patients. It can visualize active "contrast blush" indicating ongoing arterial bleeding and helps plan embolization or surgical approach.

6. Management: The Paradigm of Hemostatic Resuscitation

The management of APHA and hemorrhagic shock has undergone a fundamental shift. The historical approach of infusing large volumes of crystalloid (Normal Saline) has been abandoned in favor of "Damage Control Resuscitation" (DCR).

6.1 Hemorrhage Control

The priority is always Stop the Bleed.

• Mechanical: Direct pressure, tourniquets for limb trauma, and pelvic binders for suspected pelvic fractures to reduce pelvic volume and tamponade venous bleeding.

• Surgical: Damage control surgery involves abbreviated procedures to control hemorrhage and contamination, followed by temporary closure and transfer to the ICU for physiological restoration before definitive repair.

6.2 Massive Transfusion Protocols (MTP) and Balanced Ratios

Resuscitation with crystalloids dilutes clotting factors and oxygen carriers, worsening the lethal triad. Modern MTPs advocate for Balanced Transfusion.

• 1:1:1 Ratio: The administration of 1 unit of Packed Red Blood Cells (PRBCs), 1 unit of Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP), and 1 unit of Platelets. This ratio attempts to reconstitute whole blood.

• Evidence: The PROPPR Trial compared 1:1:1 vs. 2:1:1 ratio. While 30-day mortality was statistically similar, the 1:1:1 group had significantly fewer deaths from exsanguination in the first 24 hours and achieved hemostasis faster.

• Whole Blood: Low Titer O-Positive Whole Blood (LTO-WB) is increasingly used in civilian trauma centers. It provides RBCs, plasma, and platelets in a physiologic volume without the coagulopathy associated with fractionated products.

• MTP Activation Triggers: The Assessment of Blood Consumption (ABC) Score is commonly used. A score of ≥2 predicts the need for massive transfusion:

1. Penetrating mechanism.

2. SBP ≤ 90 mmHg.

3. HR ≥ 120 bpm.

4. Positive FAST exam.

6.3 Pharmacologic Adjuncts: Tranexamic Acid (TXA)

Tranexamic acid is a synthetic lysine analogue that inhibits fibrinolysis by blocking the binding of plasminogen to fibrin.

• Mechanism: Prevents the enzymatic breakdown of fibrin clots (fibrinolysis), which is often upregulated in trauma.

• CRASH-2 Trial: This landmark trial demonstrated that TXA reduces all-cause mortality and death due to bleeding in trauma patients. Crucially, the benefit is time-dependent.

• Timing: TXA must be administered within 3 hours of injury. Administration after 3 hours was associated with mortality due to a paradoxical pro-thrombotic effect in the later inflammatory phase.

• Dosing: A loading dose of 1 gram over 10 minutes, followed by an infusion of 1 gram over 8 hours. Recent guidelines suggest a 2 g bolus may be used in specific pre-hospital settings.

6.4 Permissive Hypotension

Also known as "hypotensive resuscitation," this strategy involves targeting a lower systolic blood pressure (typically 80-90 mmHg or MAP 60-65 mmHg) until surgical control of bleeding is achieved. The rationale is to maintain perfusion to vital organs without raising pressure enough to dislodge formed clots ("popping the clot") or dilute coagulation factors.

• Exception: Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) require a higher MAP (>80 mmHg) to maintain Cerebral Perfusion Pressure (CPP) and prevent secondary brain injury.

6.5 Calcium Replacement

Citrate, used as an anticoagulant in blood products, binds serum ionized calcium. Hypocalcemia is ubiquitous in massive transfusion and contributes to coagulopathy and cardiac depression. Protocols mandate the empiric administration of 1 gram of Calcium Chloride (or 3g Calcium Gluconate) for every 4 units of blood products transfused to maintain ionized calcium levels.

7. Complications of Massive Transfusion

While life-saving, massive transfusion carries significant iatrogenic risks that require vigilant monitoring.

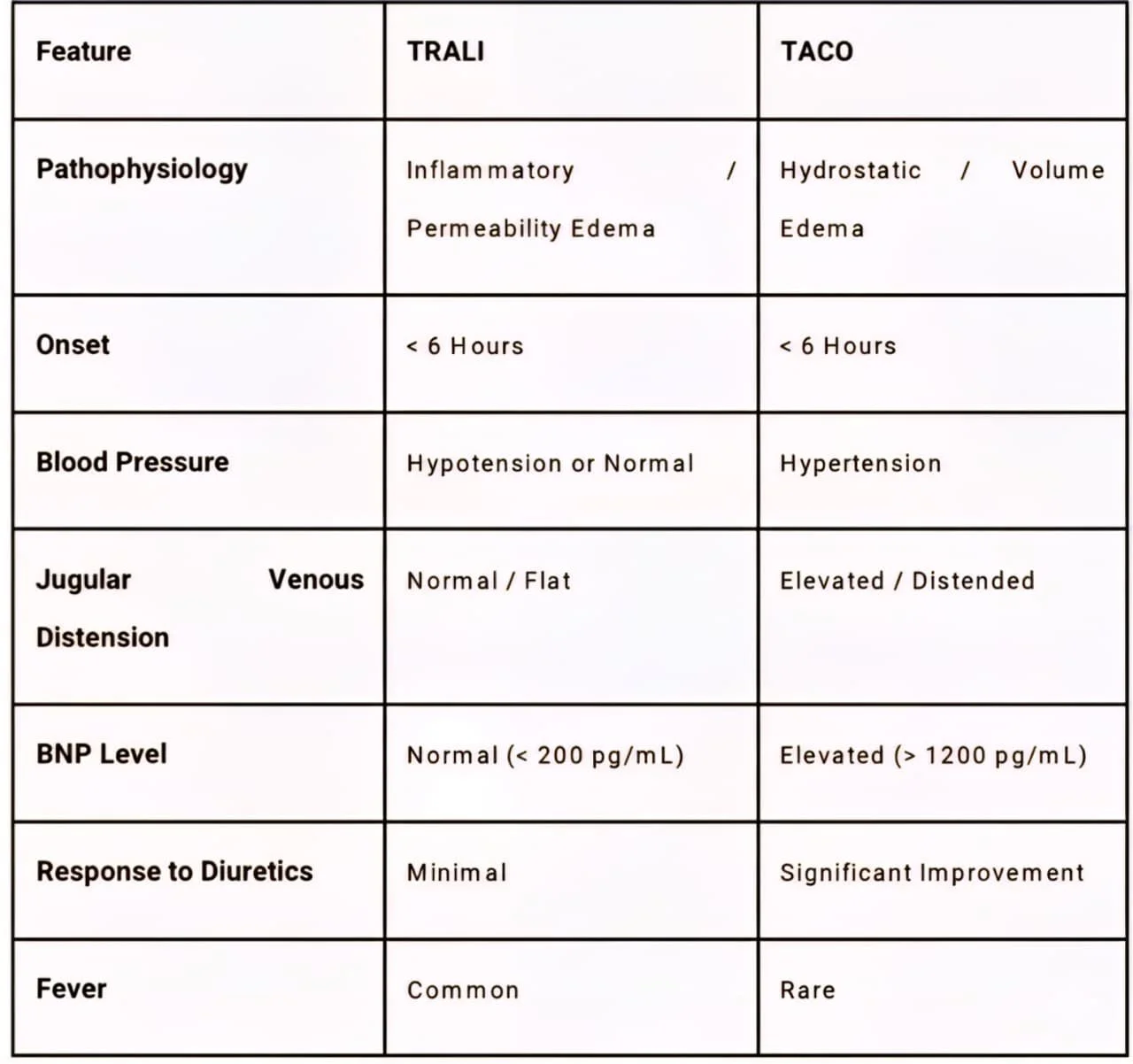

7.1 Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury (TRALI)

TRALI is a syndrome of acute lung injury that is the leading cause of transfusion-related mortality.

• Pathophysiology: It is believed to be a "two-hit" model. The first hit is the patient's underlying condition (sepsis, trauma) which primes neutrophils in the lung. The second hit is the transfusion of donor antibodies (anti-HLA or anti-HNA) or bioactive lipids that activate these neutrophils, causing endothelial damage and capillary leak.

• Clinical Presentation: Sudden onset of hypoxemia (SpO2 <90%), dyspnea, and bilateral pulmonary infiltrates ("white-out") on X-ray within 6 hours of transfusion.

• Diagnosis: It is a diagnosis of exclusion. Crucially, there is no evidence of circulatory overload (normal JVD, normal BNP).

• Management: Supportive care with oxygen and mechanical ventilation. Diuretics are not effective and may be harmful if the patient is hypovolemic.

7.2 Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload (TACO)

TACO is essentially hydrostatic pulmonary edema caused by volume overload.

• Risk Factors: Elderly patients, those with pre-existing heart failure or renal failure, and rapid transfusion rates.

• Clinical Presentation: Dyspnea, hypertension, tachycardia, and elevated JVD.

• Diagnosis: Unlike TRALI, TACO presents with signs of fluid overload: elevated BNP (>1200 pg/mL is specific), positive fluid balance, and response to diuretics.

Table 2: Distinguishing TRALI vs TACO

7.3 Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (ACS)

In massive hemorrhage, particularly abdominal trauma, aggressive fluid resuscitation can lead to visceral edema. Combined with the hematoma, this raises intra-abdominal pressure (IAP).

• Pathophysiology: IAP > 20 mmHg compresses the vena cava (reducing cardiac preload) and renal veins (causing acute kidney injury) and pushes the diaphragm up (impairing ventilation).

• Management: Surgical decompression (laparotomy) is life-saving.

8. Post-Stabilization Management: Recovery and Iron Therapy

Following hemostasis and stabilization, the therapeutic goal shifts to replenishing red cell mass. APHA results in profound iron loss; each liter of blood lost removes approximately 500 mg of iron.

8.1 The Hepcidin Blockade

A major challenge in post-hemorrhagic recovery is the inflammatory response. Trauma, surgery, and critical illness trigger the release of Interleukin-6 (IL-6), which stimulates the liver to produce hepcidin. Hepcidin is a regulatory hormone that:

1.Degrades ferroportin channels in the gut (blocking iron absorption).

2.Traps iron within macrophages (preventing recycling).

This mechanism, evolved to starve bacteria of iron ("nutritional immunity"), renders oral iron therapy largely ineffective in the acute post-inflammatory phase (first 2-4 weeks).

8.2 Intravenous vs. Oral Iron Therapy

• Intravenous (IV) Iron: Given the hepcidin blockade, IV iron is increasingly preferred for moderate-to-severe post-hemorrhagic anemia. It bypasses the gut, delivering iron directly to the reticuloendothelial system.

• Evidence: Meta-analyses show that IV iron administered post-operatively results in significantly higher hemoglobin levels at 4 weeks compared to oral iron. It is particularly indicated for patients with Hb < 10 g/dL or those intolerant to oral iron.

• Oral Iron: Appropriate for patients once inflammation subsides or for mild cases.

• Dosing statergy: Modern guidelines recommend once-daily or alternate-day dosing (e.g., 60-100 mg elemental iron) rather than multiple daily doses. High or frequent doses spike hepcidin levels for 24-48 hours, blocking subsequent absorption. Alternate-day dosing optimizes absorption and reduces GI side effects.

8.3 Erythropoiesis Stimulating Agents (ESAs)

In patients with renal failure or persistent anemia despite iron repletion, recombinant erythropoietin may be used to stimulate marrow production, though this is less common in acute trauma settings than in chronic care.

9. Future Directions and Emerging Research

The management of APHA continues to evolve with ongoing clinical trials refining transfusion triggers and adjuncts.

• PABST-BR Trial (2025): This recently completed randomized clinical trial investigated a "multifaceted anemia prevention bundle" in ICU patients. The bundle included minimized phlebotomy, clinical decision support, and IV iron. Results showed significantly improved hemoglobin recovery at 1 month post-discharge, validating the aggressive use of IV iron in critically ill survivors.

• TOPGUN-Pilot (2025): This ongoing trial is testing restrictive (Hb < 70 g/L) versus liberal (Hb < 90 g/L) transfusion triggers during surgery. The goal is to define the optimal threshold that balances oxygen delivery with the risks of transfusion.

• IRON-DEP (2025): This study explores the neuropsychiatric sequelae of APHA, specifically investigating if IV iron treatment for postpartum anemia reduces the incidence of postpartum depression compared to oral iron. This highlights the broader impact of anemia on functional recovery and mental health.

10. Conclusion

Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia is a dynamic and time-critical condition where the severity of blood loss often outpaces laboratory detection. The "hematocrit lag" is a definitive physiological feature, necessitating a reliance on hemodynamic markers-specifically tachycardia, narrowed pulse pressure, and lactate clearance-for early diagnosis. The management of APHA has matured from a rudimentary volume-replacement strategy to a sophisticated, physiology-driven paradigm of Hemostatic Resuscitation. Key components include the early use of 1:1:1 balanced transfusions, the administration of Tranexamic Acid within the 3-hour window, and the strict avoidance of the "lethal diamond" of coagulopathy.

Furthermore, the recognition of complications like TRALI and TACO requires high clinical vigilance during the resuscitation phase. Post-stabilization, the understanding of hepcidin-mediated iron blockade has shifted practice towards the earlier utilization of intravenous iron to accelerate hematologic recovery. As evidence from trials like PROPPR, CRASH-2, and the emerging PABST-BR continues to shape guidelines, the focus remains on a holistic approach: rapid hemorrhage control, precision resuscitation, and optimized recovery strategies to reduce the morbidity and mortality of this life-threatening condition.

References

1. Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia: A Comprehensive Literature Review of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Contemporary Management – ijrpr [cite_start]https://ijrpr.com/uploads/V6ISSUE10/IJRPR54024.pdf

2. Chronic Anemia - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534803/

3. Acute Anemia - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf – NIH https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537232/

4. Anemia Screening - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499905/

5. Hemorrhagic Shock - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470482/

6. Why does hematocrit (Hct) level lag behind 24 to 48 hours after the onset of bleeding? https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/hematocrit-levels-after-bleeding

7. Fluid Shifts After Hemorrhage - The Blood Project https://www.thebloodproject.com/fluid-shifts-hemorrhage/

8. Hemoglobin Drops Within Minutes of Injuries and Predicts Need for an Intervention to Stop Hemorrhage | Request PDF – ResearchGate https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312061324

9. Massive transfusion: a review - Moore - Annals of Blood https://aob.amegroups.org/article/view/4243/html

10. Massive Transfusion for Trauma - Washington State Department of Health https://doh.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2022-02/646174.pdf

11. Ep 152 The 7 Ts of Massive Hemorrhage Protocols - Emergency Medicine Cases https://emergencymedicinecases.com/massive-hemorrhage-protocols/

12. Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia: 7 Key Facts About Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment https://www.khealth.com/learn/anemia/acute-posthemorrhagic/

13. Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia: Symptoms, Causes, And Treatment – HealthMatch https://healthmatch.io/anemia/acute-posthemorrhagic-anemia

14. Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia Houston | D62 Code & Treatment – GastroDoxs https://www.gastrodoxs.com/blog/acute-posthemorrhagic-anemia-houston-d62-code-treatment

15. Global health agencies issue new recommendations to help end deaths from postpartum haemorrhage https://www.who.int/news/item/10-10-2023-global-health-agencies-issue-new-recommendations-to-help-end-deaths-from-postpartum-haemorrhage

16. Intravenous Iron Successfully Treats Postoperative Anemia, Oral Ineffective | HCPLive https://www.hcplive.com/view/intravenous-iron-successfully-treats-postoperative-anemia-oral-ineffective

17. Practical Anemia Bundle and Hemoglobin Recovery in Critical Illness: A Randomized Clinical Trial - PMC – NIH https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11019283/

18. Acute Anemia – MDSearchlight https://mdsearchlight.com/acute-anemia/

19. Lactate clearance as a predictor of mortality in trauma patients Ovid https://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/abstract/2009/01000/lactate_clearance_as_a_predictor_of_mortality_in.13.aspx

20. Serum Lactate and Lactate Clearance in Predicting Outcome in Polytrauma Patient https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5453005/

21. Failure to Clear Elevated Lactate Predicts 24-Hour Mortality in Trauma Patients – PMC https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3574574/

22. What are the classes of hemorrhagic shock? - Dr.Oracle https://www.doctororacle.com/classes-of-hemorrhagic-shock/

23. Examination of the utility of serum lactate and base deficit in hemorrhagic shock – PMC https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4163539/

24. Why does a 2-liter blood loss cause a base deficit of -6, indicating metabolic acidosis? https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acid-base-disturbances-in-shock

25. What is Hemorrhagic Shock? Understanding the Basics and Its Implications – CVRTI https://cvrti.utah.edu/what-is-hemorrhagic-shock/

26. Clinical review: Hemorrhagic shock - PMC - PubMed Central https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3218991/

27. Happy TRALIdays: An Overview of Trauma Resuscitation and Transfusion Complications https://tamingthesru.com/blog/academics/trali-taco

28. Anemia Due to Acute Blood Loss | Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 22nd Edition https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=3251§ionid=272719131

29. Role of serum lactate as prognostic marker of mortality among emergency department patients with multiple conditions: A systematic review - PMC – NIH https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9373187/

30. Reticulocyte Count - Lab Tests Online https://testing.com/tests/reticulocyte-count/

31. Reticulocyte count (retic count) and interpretations - Labpedia.net https://www.labpedia.net/hematology/reticulocyte-count/

32. Reticulocyte production index – Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reticulocyte_production_index

33. Blood Smear - UF Health https://ufhealth.org/medical-test/blood-smear

34. Mechanisms | eClinpath https://eclinpath.com/hematology/anemia/mechanisms/

35. Adult Massive Transfusion Protocol - McGovern Medical School - UTHealth Houston https://med.uth.edu/surgery/trauma-manual/adult-massive-transfusion-protocol/

36. UAMS MEDICAL CENTER ACS SERVICES MANUAL SUBJECT: Massive Transfusion Protocol UPDATED https://trauma.uams.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2022/02/Massive-Transfusion-Protocol.pdf

37. Effect of a fixed-ratio (1:1:1) transfusion protocol versus laboratory-results-guided transfusion in patients with severe trauma: a randomized feasibility trial - PMC – NIH https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4163539/

38. CRASH-2 Study of Tranexamic Acid to Treat Bleeding in Trauma Patients: A Controversy Fueled by Science and Social Media - PubMed Central https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4163539/

39. What is the appropriate dosing of Tranexamic Acid (TXA) for bleeding? - Dr.Oracle https://www.doctororacle.com/txa-dosing-trauma/

40. The CRASH-2 trial: Tranexamic acid in trauma patients [Classics Series] | 2 Minute Medicine https://www.2minutemedicine.com/the-crash-2-trial-tranexamic-acid-in-trauma-patients/

41. Trial protocol - The CRASH-2 trial: a randomized controlled trial and economic evaluation of the effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events and transfusion requirement in bleeding trauma patients – NCBI https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1403753/

42. Tranexamic Acid - McGovern Medical School - UTHealth Houston https://med.uth.edu/surgery/trauma-manual/tranexamic-acid/

43. TACO and TRALI: biology, risk factors, and prevention strategies - PMC - PubMed Central https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6370425/

44. Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) - Professional Education https://professionaleducation.blood.ca/en/transfusion/clinical-guide/transfusion-related-acute-lung-injury-trali

45. Anemia Due to Acute Blood Loss | Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 21e AccessPharmacy https://accesspharmacy.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=3095§ionid=265416043

46. Oral versus intravenous iron therapy for postpartum anemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis - PMC - PubMed Central https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7060493/

47. Iron Deficiency Anaemia in Adults: Oral and Intravenous Iron Therapy Treatment - Right Decisions https://rightdecisions.scot.nhs.uk/m/2295/ida.pdf

48. Iron-Deficiency Anemia - Hematology.org https://www.hematology.org/education/patients/anemia/iron-deficiency

49. Guideline for the Management of Anaemia in the Perioperative Pathway https://cpoc.org.uk/sites/cpoc/files/documents/2025-04/CPOC-AnaemiaGuideline2025.pdf

50. Study Details | NCT05167734 | Practical Anemia Bundle for SusTained Blood Recovery | ClinicalTrials.gov https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05167734

51. Study Details | NCT06718439 | Hemoglobin Levels for Blood Transfusions During and After Surgery ClinicalTrials.gov https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06718439

52. Study Details | NCT06833788 | Treatment of Anaemia After Caesarean With Intravenous Versus Oral Iron and Postpartum Depression ClinicalTrials.gov https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06833788

53. Cochrane Review: IV vs Oral Iron for Iron Deficiency Anemia in Pregnancy https://www.cochrane.org/CD013242/PREG_intravenous-versus-oral-iron-treatment-iron-deficiency-anaemia-pregnancy