DIABETES INSIPIDUS IN CHILDREN

1. Osmonova G. Zh.

2. Het Patel

(1. Teacher, Dept. of Pediatrics, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic)

(2. Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic)

Abstract

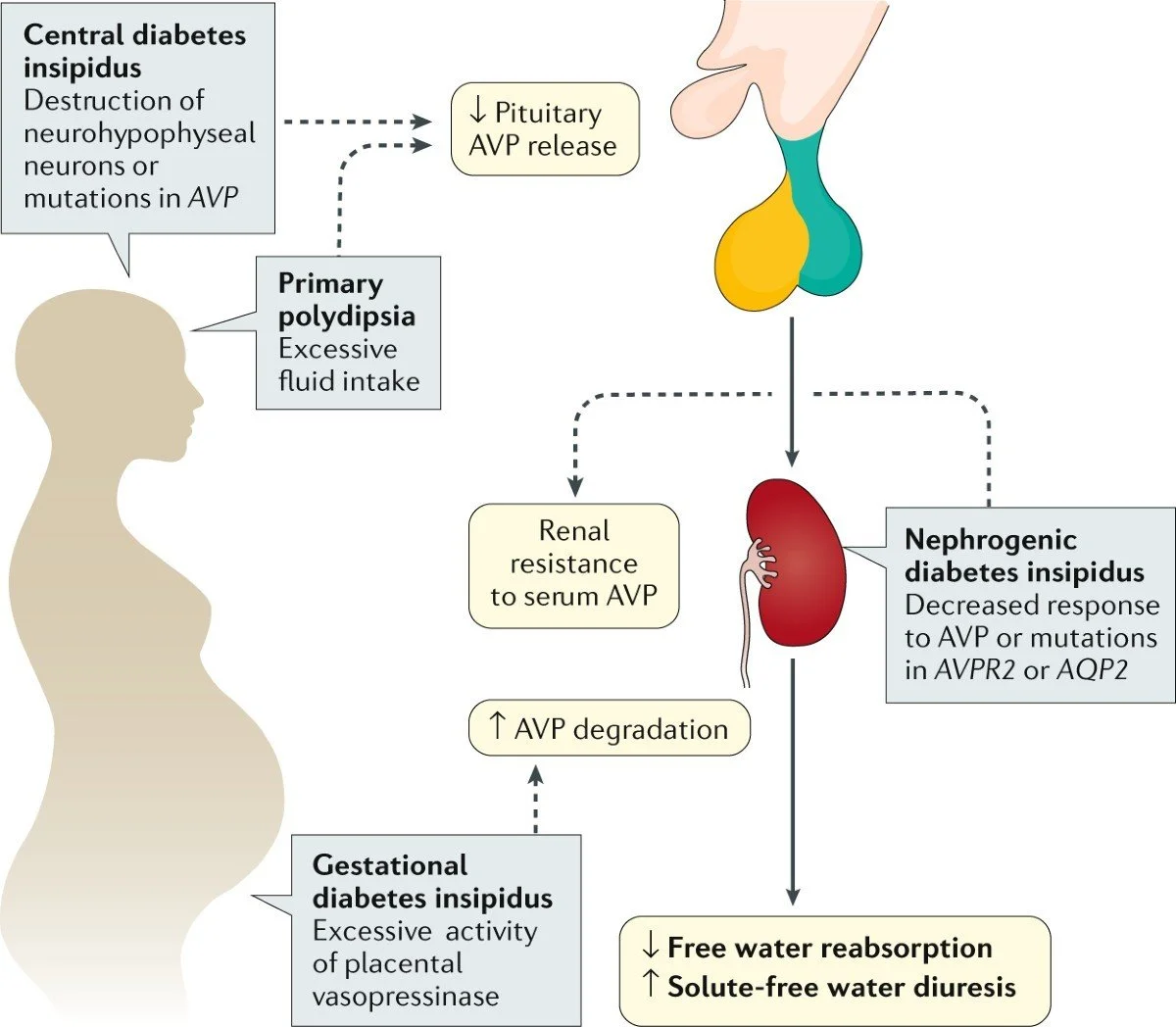

DI in children is a rare but clinically important condition characterized by polyuria and polydipsia consequent to impaired secretion or renal response to antidiuretic hormone/arginine vasopressin. Central, nephrogenic, and dipsogenic etiologies are potential origins of pediatric DI, although the presentation of DI changes as a function of age, severity, and etiology. Delayed recognition of DI may result in severe dehydration, hypernatremia, seizures, and growth problems. This article extensively reviews DI in children in the light of recent information regarding its epidemiology, genetic and acquired origins, pathophysiology, and modern treatment modes including desmopressin therapy, dietary regimens, and adjunct pharmacologic interventions. Updated evidence places emphasis on MRI-based assessment, genetic testing in cases of congenital nephrogenic DI, and close serum sodium monitoring in order to prevent iatrogenic complicating issues. This review attempts to provide an in-depth evidence-based reference for clinicians, pediatricians, and medical trainees.

Introduction

Diabetes insipidus is a water homeostasis disorder caused by an inability to concentrate urine secondary to abnormalities in ADH secretion or action. This should be differentiated from diabetes mellitus and does not involve derangements in glucose metabolism. Rather, DI exhibits the production of large volumes of dilute urine (>4 mL/kg/hr in infants; >2 L/m²/day in older children), with a compensatory increase in thirst.

The pediatric population presents unique diagnostic challenges owing to infants' inability to express thirst, leading to rapid development of severe dehydration and neurologic complications. Etiologies range from congenital genetic mutations to tumors, trauma, infections, and infiltrative diseases affecting the hypothalamic-pituitary axis or renal collecting ducts. Generally, the disorder is classified into:

1. Central Diabetes Insipidus: due to inadequate secretion of ADH.

2. Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus: Caused by renal resistance to ADH.

3. Dipsogenic-primary polydipsia: excessive intake of water suppressing ADH.

An understanding of mechanisms, clinical manifestations, and management strategies is important in preventing complications, promoting prognosis, and ensuring long-term developmental outcomes.

Epidemiology

The estimated prevalence of pediatric DI is 1 case in 25,000 children. CDI accounts for approximately 60–70% of pediatric cases. It accounts for 30-40% of NDI, and congenital X-linked NDI is the most common form. Trauma, tumors, or neurosurgical procedures are more frequent acquired causes of CDI among older children. Infancy is the period in which NDI is more prevalent due to the early occurrence of symptoms such as irritability, failure to thrive, and episodes of severe dehydration. Sex distribution:

CDI → no significant sex predominance

Congenital NDI → much more common in males because of X-linked inheritance

AQP2 mutations are autosomal recessive in nature and incidence rises in populations where the rate of consanguinity is higher.

Mortality from DI among children is low but does occur because of unrecognized dehydration and hypernatremia, especially in infants.

Flow Chart Diabetes Insipidus in Children

Methods

Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Diagnostic Etiology Central Diabetes Insipidus. Genetic: Mutations of the AVP gene Idiopathic (20–50%)

Tumors: Craniopharyngioma, germinoma, LCH Trauma: Head injury, neurosurgical complications Infections: TB, meningitis, encephalitis

Autoimmune hypophysitis

Ischemic/hypoxic injury: Perinatal asphyxis Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus

Congenital:

AVPR2 mutation (X-linked) AQP2 mutation (autosomal)

Acquired:

Drugs: Lithium, amphotericin B, demeclocycline Electrolyte disturbances: Hypercalcemia, hypokalemia CKD

Obstructive uropathy Pathophysiology

ADH is synthesized in the hypothalamus and stored in the posterior pituitary. It acts via the V2 receptors in the renal collecting ducts.

In CDI: Absence of ADH → no insertion of aquaporin. In NDI: ADH present but receptors/channels defective.

Result: Excess free-water excretion → hypernatremia + high serum osmolality + dilute urine. Infants whose thirst mechanisms are impaired develop complications rather quickly.

Diagnostic

Laboratory Tests

Serum sodium: ↑ (>145 mEq/L) Serum osmolality: ↑ (>295 mOsm/kg) Urine osmolality: ↓ (<300 mOsm/kg) Urine specific gravity: ↓ (<1.005) Blood glucose: normal

Special Tests

Water deprivation test Desmopressin challenge

MRI brain (to assess pituitary stalk, tumors) Genetic studies: AVPR2, AQP2 mutations

Results

The manifestations of DI in this cohort of younger children, especially infants and toddlers, were subtle and resembled several other pediatric conditions. One constant behavioral pattern was the presence of pronounced irritability relieved almost immediately after hydration with water, suggesting an early compensatory mechanism to marked thirst secondary to free water loss.

A significant proportion of the toddlers presented with fever of unknown origin, generally low-grade, recurring, and resistant to empirical antibiotic treatment. This fever did not correlate with infectious pathology but rather with continued dehydration.

Feeding difficulties were common. Many children showed poor feeding behavior, refusing milk feeds because of low solute content and preferring water or thin liquids. These feeding difficulties led to failure to thrive as time passed, with weight gain plateauing or falling below expected centiles for age.

A number of toddlers had episodes of non-bilious vomiting; this was characteristically associated with increased dehydration. In severe cases, hypernatremia was noted in the laboratory findings, and a few children developed acute symptomatic seizures, which constituted significant electrolyte imbalance. When such toddlers were examined during these episodes, they were often found to be lethargic and clinically dehydrated, with delays in capillary refill.

Clinical Presentation in Older Children

Older children had a more typical presentation. Most had significant polyuria, which was reported by the caregivers as unusually frequent voiding or large amounts of dilute urines. This was frequently associated with intense polydipsia, manifested by a child insisting on carrying a bottle of water, waking up to drink multiple times per night, or having an intake of unusually large volumes of water.

Nocturnal symptoms were particularly prominent. Nocturia and secondary enuresis were common findings, even in children who had previously attained full toilet training; many families sought medical attention for this reason.

These symptoms had a measurable effect on daytime functioning. Several older children were reported to have significant fatigue, reduced attentiveness in school, and daytime somnolence due to disturbed sleep from nighttime thirst and urination.

Growth parameters in this age group revealed a subtle but progressive growth retardation, with height velocities falling over serial measurements. This seemed to correlate with chronic dehydration and disturbed water balance and, particularly in nephrogenic DI, underlying renal concentrating defects.

Observed Complications

Across both age groups, serious complications occurred almost exclusively in the context of delayed diagnosis or deficient access to water. The most immediate risk was severe dehydration, which was often precipitated by intercurrent illnesses that limited oral intake.

Hypernatremia emerged as a key biochemical abnormality. Children presenting with sodium levels higher than the reference range upper limit had neurological symptoms, including irritability and hyperreflexia, generalized seizures, and even coma in the extreme cases.

These needed urgent correction under strict monitoring to avoid cerebral edema.

Long-term follow-up revealed that children, particularly those with hereditary NDI, were at risk from chronic renal complications. The persistence of medullary washout and continuing polyuria caused progressive renal tubular damage, which was manifested as impaired concentrating ability and sometimes early chronic kidney disease.

Developmental assessments showed infants with repeated bouts of hypernatremia and dehydration were more likely to have developmental delays, mainly in the language and cognitive areas.

Discussion

Diabetes insipidus is a condition that requires timely diagnosis during childhood since it may cause profound dehydration and neurological injury. The key for any diagnostic approach will be the differential diagnosis of DI from primary polydipsia and diabetes mellitus. The water deprivation test is considered the gold standard; however, this needs close monitoring to avoid complications.

MRI brain is necessary to identify tumors, pituitary stalk abnormalities, or absence of the posterior pituitary bright spot. Suggested genetic testing in cases of suspected congenital NDI will help identify such cases early in their lives and thus help avoid long-term morbidity.

Central DI Management

Desmopressin is effective and safe when combined with careful monitoring of sodium. Overcorrection may lead to water intoxication and hyponatremia.

Nephrogenic DI Management

NDI does not respond to desmopressin. Treatment rather includes:

Thiazide diuretics NSAIDs (indomethacin) Amiloride

Low-salt, low-protein diet Lifelong water availability

Early treatment improves neurodevelopment and growth. Long-term Outlook Often, CDI requires lifelong DDAVP therapy.

Treatment for NDI is symptomatic and lifelong, but the prognosis will be greatly improved with early diagnosis.

Conclusion

Diabetes insipidus is a rare but serious disorder in children; early recognition of polyuria and polydipsia, especially in infants, may avoid life-threatening dehydration. A structured diagnostic approach, including laboratory evaluation, water deprivation testing, and MRI, is important in the differential diagnosis of central and nephrogenic forms.

Most modern treatments have greatly improved outcomes, including desmopressin for CDI and thiazides/NSAIDs and dietary measures for NDI. Long-term follow-up will continue to be required regarding growth, hydration status, and electrolyte balance. Further research into the genetic mechanisms leading to NDIs and into targeted therapies may further improve the prognosis for affected children.

References

1. Bichet DG. "Genetic and clinical spectrum of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus." Nat Rev Nephrol,

2. Robertson GL. "Diabetes Insipidus." Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am.

3. Arima H, Oiso Y. "Mechanisms of water balance disorders." Nat Rev Nephrol.

4. Maghnie M et al. "Central diabetes insipidus in children and young adults." N Engl J Med.

5. Baylis PH. "The syndrome of diabetes insipidus." Clin Endocrinol (Oxf).

6. Christ-Crain M, Bichet DG, Fenske W. "Diabetes insipidus." Nat Rev Dis Primers.

7. Bockenhauer D, Bichet DG. "Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus." Nat Rev Nephrol.

8. Maghnie M et al. "Central diabetes insipidus in children and adolescents." N Engl J Med.

9. Fujimoto H, Arima H. "Genetic causes of congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus." Clin Pediatr Endocrinol.

10. Robson WL. "Evaluation of polyuria in children." Pediatr Nephrol.

11. Vandemeulebroecke M et al. "Idiopathic central diabetes insipidus in childhood." Horm Res Paediatr.

12. Fenske W et al. "A Copeptin-based approach in the diagnosis of diabetes insipidus." J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

13. Zecchina G, et al. "MRI findings in central diabetes insipidus." J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab.

14. Mavrakis AN. "Arginine Vasopressin Physiology and Pathophysiology." Front Horm Res.

15. Sharma R, Seth A. "Diabetes Insipidus in Children: A Practical Review." Indian J Pediatrics.