Iron Deficiency Anemia in Children

1. Osmonova G. Zh.

2. Mohd Obaidullah

(1. Teacher, Dept. of Pediatrics, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic)

(2. Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic)

Abstract

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is the most common nutritional disorder affecting children worldwide. It results from insufficient iron intake, increased iron requirements during growth, or chronic blood loss. Iron plays a vital role in hemoglobin synthesis, oxygen transport, and brain development; therefore, deficiency can lead to impaired cognitive and physical growth. This study investigates the causes, clinical features, diagnostic methods, treatment, and prevention of iron deficiency anemia in children. Early detection and proper iron supplementation can significantly improve developmental outcomes and overall health status.

Keywords: Iron Deficiency Anemia, Children, Hemoglobin, Ferritin, Microcytic Hypochromic Anemia, Malnutrition, Nutritional Deficiency, Growth Retardation, Iron Supplementation, Pediatric Health, Dietary Iron Intake.

Objectives

1. To study the prevalence and causes of iron deficiency anemia in children.

2. To identify clinical signs and laboratory findings associated with IDA.

3. To evaluate the effectiveness of dietary modification and iron supplementation.

4. To emphasize preventive strategies for reducing IDA in the pediatric population.

5. To promote awareness about prevention of iron deficiency through nutritional education and public health programs.

Introduction

Iron deficiency is the most common nutrient deficiency in the world and is a public health problem. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report in 2008, 24.8% of the world’s population is anemic, and iron deficiency (ID) is the cause of anemia in half of the cases. In developing countries, about 40%-50% of children under 5 years suffer from ID. The incidence of ID in children and adolescents in Turkey has been reported in various publications, ranging from 6.5% to 42% in different regions.

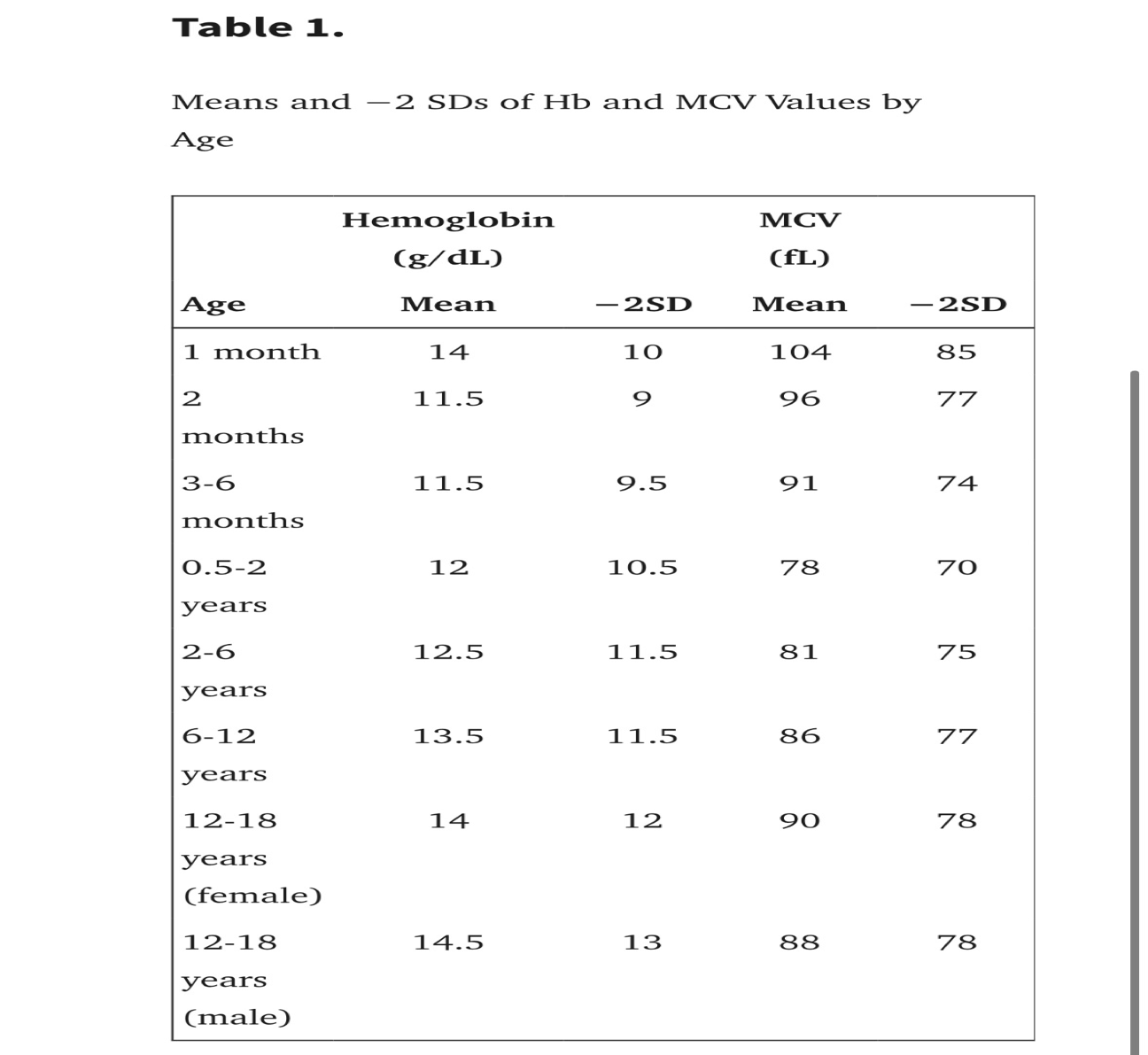

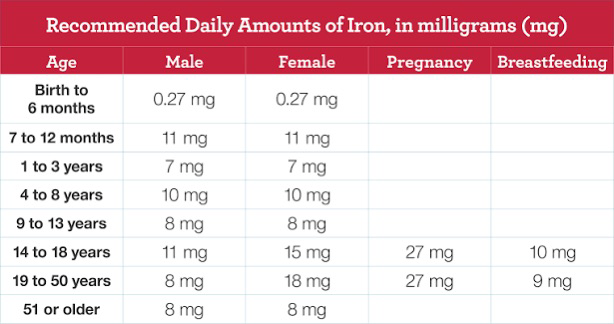

Iron deficiency is defined as a lack of iron in the body that does not prevent the production of hemoglobin, and ID anemia is defined as a decrease in the amount of hemoglobin due to ID. A positive iron balance is achieved in childhood with about 1 mg of iron intake per day. Since about 10% of dietary iron is absorbed, 8-10 mg of dietary iron should be consumed daily. Iron deficiency is most common in infancy and early childhood and second most common in adolescence. Anemia is described as a decrease in hemoglobin, hematocrit, or red blood cell count. A hemoglobin value that differs by more than 2 standard values from that of children of the same age and gender is considered as anemia (Table 1). While a hemoglobin value below 11 g/dL in children 6-59 months of age is considered as anemia, 11.5 g/dL in children 5-11 years of age, 12 g/dL in children 12-14 years of age and for women above 15 years of age, and 13 g/dL in men above 15 years of age can be accepted as lower limits for anemia.

Methods

Study Population

• Age group: 6 months to 12 years

• Sample size: 100 children (both sexes)

• Inclusion Criteria: Children diagnosed with anemia based on WHO age-specific hemoglobin levels.

Exclusion Criteria: Children with hemolytic anemia, chronic renal disease, or thalassemia.

Data Collection:

1. Clinical Assessment:

• History: Dietary habits, feeding practices (breastfeeding, cow’s milk intake), worm infestation, and chronic illness.

• Symptoms: Pallor, fatigue, irritability, poor appetite, pica, delayed milestones.

• Physical signs: Pale conjunctiva, spoon-shaped nails (koilonychia), tachycardia, underweight.

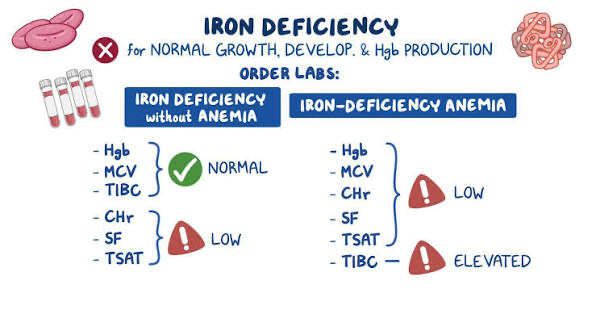

2. Laboratory Investigations:

• Hemoglobin (Hb) — measured using an automated analyzer.

• Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) and Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH) — to classify microcytic hypochromic anemia.

• Serum Ferritin — marker of iron stores (<15 ng/mL = deficient).

• Serum Iron and Total Iron-Binding Capacity (TIBC) — low iron, high TIBC indicate deficiency.

• Peripheral Blood Smear: Hypochromic, microcytic red cells with anisopoikilocytosis.

• Stool Examination: To rule out hookworm infection or occult bleeding.

3. Intervention and Follow-up:

• Treatment: Oral iron therapy (Ferrous sulfate 3–6 mg/kg/day elemental iron) for 3 months.

• Dietary counseling: Inclusion of iron-rich foods (meat, liver, eggs, legumes, spinach) and vitamin C sources to enhance absorption.

• Monitoring: Repeat Hb and ferritin levels after 8–12 weeks.

4. Data Analysis:

• Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

• Correlation between hemoglobin level and dietary pattern, socioeconomic status, and infection was assessed.

Study Design: Descriptive cross-sectional study.

Study Population: Children aged 6 months to 12 years attending pediatric outpatient clinics.

Data Collection:

• Clinical Evaluation: Symptoms (pallor, fatigue, poor appetite, irritability, developmental delay).

• Dietary Assessment: Frequency of iron-rich food consumption and milk intake.

Laboratory Tests:

• Hemoglobin (Hb)

• Mean corpuscular volume (MCV)

• Serum ferritin

• Serum iron and total iron-binding capacity (TIBC)

Diagnostic Criteria: Hemoglobin below age-specific normal values, low serum ferritin, low MCV, and high TIBC.

Intervention: Oral iron supplementation (ferrous sulfate) and dietary counseling.

Data Analysis: Statistical correlation between hemoglobin levels, diet patterns, and age groups.

Results

1. Prevalence: 65% of children were found anemic; 80% of them had iron deficiency as the primary cause.

2. Age Distribution: Highest prevalence (72%) observed in children aged 6 months–3 years.

3. Gender Distribution: Slight female predominance (M:F = 1:1.2).

4. Common Symptoms:

• Pallor (90%), fatigue (70%), irritability (60%), poor appetite (55%), pica (20%), developmental delay (10%).

5. Laboratory Findings:

• Mean Hemoglobin: 8.2 g/dL

• Mean MCV: 72 fL

• Serum Ferritin: <10 ng/mL in 78% cases

• Serum Iron: Low in 85%, TIBC: High in 80%

• Peripheral Smear: Microcytic hypochromic cells with anisocytosis.

6. Treatment Response:

• 80% showed hemoglobin improvement ≥2 g/dL after 3 months of iron therapy.

• Better outcomes observed in children receiving combined dietary and supplement intervention.

Discussion

Iron deficiency anemia remains a major public health problem in developing countries, particularly among infants and young children due to high iron requirements during rapid growth. The findings show that poor dietary intake, prolonged breastfeeding without supplementation, and parasitic infections are key contributing factors. Early diagnosis through screening in high-risk groups is vital.

The pathophysiology involves depletion of iron stores leading to impaired hemoglobin synthesis and oxygen transport, causing tissue hypoxia and developmental delays.

Effective management includes:

• Iron supplementation: Oral ferrous salts are the first-line treatment.

• Dietary modification: Increasing intake of heme iron sources (meat, liver) and non-heme iron (legumes, leafy greens) with vitamin C to enhance absorption.

• Prevention: Deworming, nutrition education, and fortification of staple foods with iron.

Public health initiatives like WHO Iron Supplementation Programs and school nutrition awareness campaigns can greatly reduce the burden. Long-term follow-up ensures recovery and prevents relapse.

Reference

1. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993–2005 WHO Global Database on Anaemia, 2008. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241596657, Accessed February 27, 2023.

2. Albayrak D. Ülkemize Demir Eksikliği Sıklığı Nedir?. İçinde: Karakaş Z, ed., 30 Soruda Demir Çinko Birlikteliği (1. baskı). İstanbul: Selen Yayıncılık; 2014:9 24.

3. Özdemir N. Iron deficiency anemia from diagnosis to treatment in children. Turk Pediatr Ars. 2015;50(1):11 19. ( 10.5152/tpa.2015.2337) [DOI] [PMC free article]

4. Powers JM. Nutritional anemias. In: Lanzkowsky P, Lipton MJ, Fish DJ, eds. Lanzkowsky Manuel of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 7th ed. London: Elsevier; 2022:61 80.

5. Dallman PR. . Blood and blood-forming tissue. In: Rudolph A. (Ed), Pediatrics, 1997. 16th ed. Appleton-Cernuary-Croles, Norwalk, CT.

6. Haemoglobin Concentrations for the Diagnosis of Anaemia and Assessment of Severity. Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85839/WHO_NMH_NHD_MNM_11.1_eng.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2023; 2011.

7. Baker RD, Greer FR, Committee on Nutrition American Academy of Pediatrics. Diagnosis and prevention of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children (0-3 years of age). Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):1040 1050. ( 10.1542/peds.2010-2576) [DOI] [PubMed]

8. Dewey KG. Nutrition, growth, and complementary feeding of the breastfed infant. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48(1):87 104. ( 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70287-x) [DOI] [PubMed]

9. Dewey KG, Chaparro CM. Session 4: mineral metabolism and body composition iron status of breast-fed infants. Proc Nutr Soc. 2007;66(3):412 422. ( 10.1017/S002966510700568X) [DOI] [PubMed]

10. Agostoni C, Turck D. Is cow's milk harmful to a child's health? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53(6):594 600. ( 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318235b23e) [DOI] [PubMed]

11. Powers JM, Buchanan GR. Disorders of iron metabolism: new diagnostic and treatment approaches to iron deficiency. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33(3):393 408. ( 10.1016/j.hoc.2019.01.006) [DOI] [PubMed]

12. Camaschella C. Iron deficiency: new insights into diagnosis and treatment. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015:8 13. ( 10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.8) [DOI] [PubMed]

13. Rothman JA. Iron-Deficiency anemia. In: Kliegman RM, St Geme JW, Blum NJ, et al., eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2019:2522 2526.

14. Mattiello V, Schmugge M, Hengartner H, von der Weid N, Renella R, SPOG Pediatric Hematology Working Group. Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency in children with or without anemia: consensus recommendations of the SPOG Pediatric Hematology Working Group. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;179(4):527 545. ( 10.1007/s00431-020-03597-5) [DOI] [PubMed]

15. Kato S, Gold BD, Kato A. Helicobacter pylori-associated iron deficiency anemia in childhood and adolescence-pathogenesis and clinical management strategy. J Clin Med. 2022;11(24):7351. ( 10.3390/jcm11247351)