Acquired Hemolytic Anemia in Children

1. Abhishek Raja

2. Osmonova G. Zh.

(1. Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.

2. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.)

Abstract

Acquired hemolytic anemia in children encompasses a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by the premature destruction of RBCs due to extrinsic factors acting on otherwise structurally normal erythrocytes. The condition ranges from mild, self-limited hemolysis to fulminant, life-threatening anemia. Immune-mediated mechanisms, in particular, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, prevail in the pediatric age group, whereas the nonimmune causes-to wit, infections, drugs, mechanical injury, and systemic diseases-play a contributory role to a very considerable extent. This enhanced review encompasses epidemiology, immunopathogenesis, molecular mechanisms, detailed clinical correlations, advanced diagnostics, management algorithms, complications, prognosis, and preventive strategies, and proposed graphs and diagrams for academic use.

Introduction and Definitions

Hemolytic Anemia is a type of anemia caused because of decreased red blood cell survival rates (<120 days). This is due to the rate of its destruction exceeding the bone marrow’s compensatory capacity. There are several types of hemolytic anemias among children. They can be categorized as follows

· Inherited (intrinsic) hemolytic anemias – membrane defects, enzyme deficiencies, hem

· Acquired or extrinsic anemias – immune and nonimmune destruction of normal erythrocytes

Sickle cell hemolytic anemia is a significant acquired hemolytic anemia because of its acute onset, potential reversibility, and association with systemic disease. Early diagnosis is important, especially in infants and young children, whose acute hemoglobin loss can lead to cardiac failure.

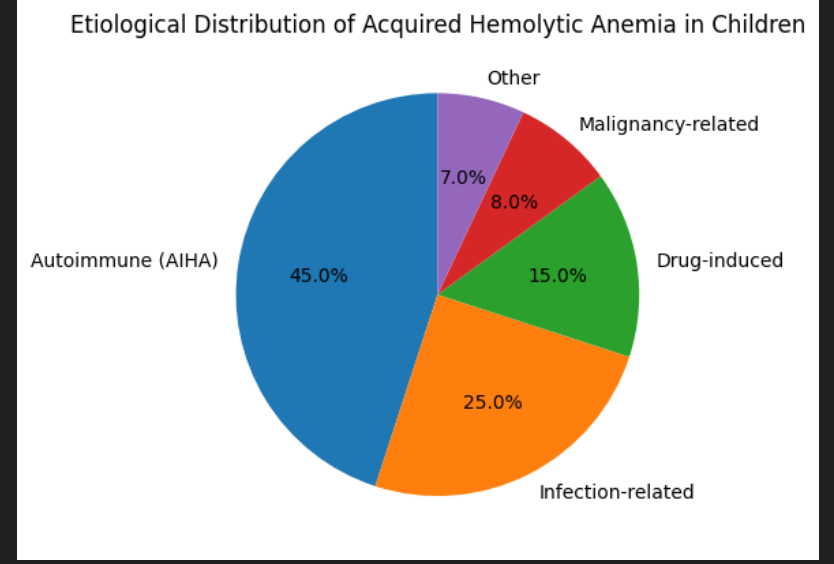

Epidemiology

Acquired hemolytic anaemia is less common in children than inherited forms but disproportionately accounts for many hematologic emergencies.

· Incidence of pediatric AIHA: ~0.2–0.4 cases per 100,000 children per year

· Bimodal age distribution: infancy (<2 years) and adolescence

· Slight female predominance, particularly in autoimmune‑associated cases

· Secondary AIHA accounts for up to 40–50% of cases in tertiary‑care cohorts

Thus, geographical variation exists due to differences in infectious disease prevalence, access to vaccination, and diagnostic capacity.

Classification of Acquired Hemolytic Anemia

3.1 Immune-mediated Hem

3.1.1. Autoimmune Hem

AIHA occurs when autoantibodies target RBC antigens on the surface of red cells, resulting in their premature destruction.

The classification based on thermal reactivity:

· Warm AIHA (IgG, 37°C active

· Cold agglutinin disease (IgM, active

· Mixed AIHA

· Paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria: This

Based on Etiology:

· Primary (idiopathic)

· Secondary (Infection-linked, Autoimmune disease, malignancy

3.1.2 Alloimmune Haemolytic Anaemia

Post‑transfusion hemolysis

Haemolytic disease due to maternal antibodies (rare beyond neonatal period)

3.2 Non‑Immune Acquired Haemolytic Anaemia

Infection‑related hemolysis

Drug‑induced non‑immune hemolysis

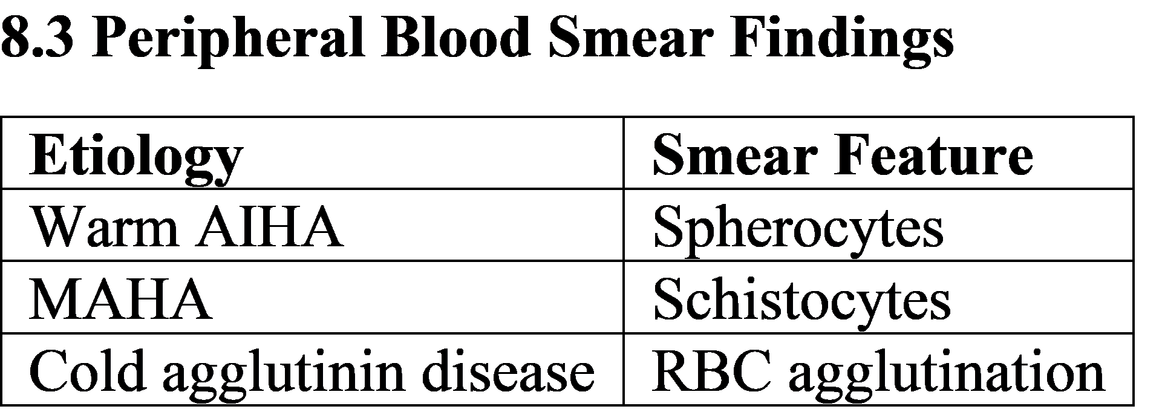

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA)

Mechanical hemolysis

Hypersplenism

Immunopathogenesis

4.1 Mechanisms of Autoantibody

Autoantibody production can be triggered by the

Molecular mimicry following infection

Immune tolerance loss

Polyclonal B-cell Activation

Dysfunction of regulatory T cells

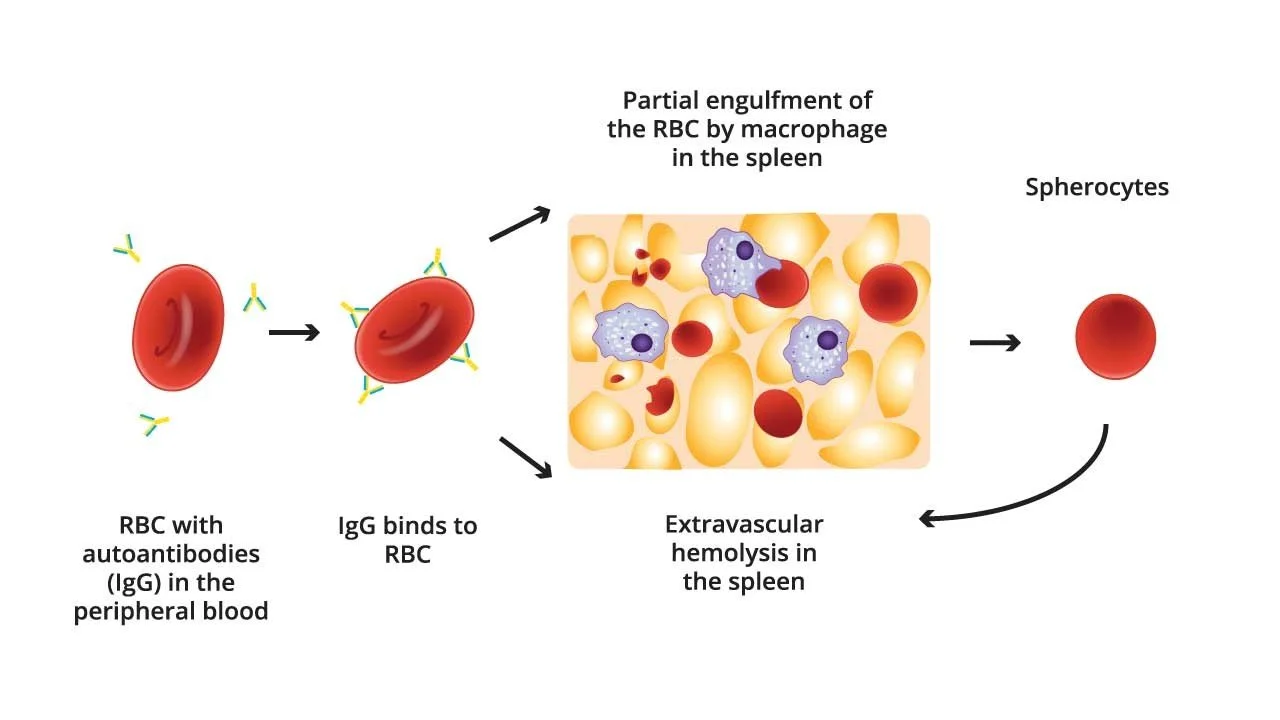

4.2 Ex- & In vivo Hem

· Hemolysis outside

· IgG-coated RBCs identified by Fc receptors of splenic macrophages

· Partial Phagocytosis → Spherocyte

· Most common in Warm AIHA

· Intravascular Hem

· Complement activation (C5-C9)

· Release of free hemoglobin in plasma

· Identified in cold antibody disease and PCH

Infection‑Associated Acquired Hemolysis

Common triggers include:

Viral: EBV, CMV, influenza, hepatitis viruses

Bacterial: Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae

Parasitic: Malaria (non‑immune and immune mechanisms)

Mechanisms include:

RBC invasion, direct

Immune complex formation

Complement activation

c Cytokine-mediated membrane damage

Drug‑Induced Hemolytic Anemia

6.1 Immune Drug-Induced hemolysis

Hapten-induced (Penicillin type )

Immune complex type (Quinidine)

Autoantibody induction (methldopa)

6.2 Non-Immune Drug induced hemolysis

Oxidative stress (particularly in G6PD deficiency)

Direct membrane toxicity

Common implicated drugs:

Antibiotics (cephalos

Antimal

Antiepilept

Clinical Manifestations

7.1 General Symptoms

Pallor

Fatigue

Dyspnea

Poor feeding (infants)

7.2 Hemolysis‑Specific Features

Jaundice

Dark or cola‑colored urine

Splenomegaly

Gallstone‑related abdominal pain (chronic hemolysis)

7.3 Severe Presentations

Acute hemolytic crisis

High‑output cardiac failure

Shock (rare but possible)

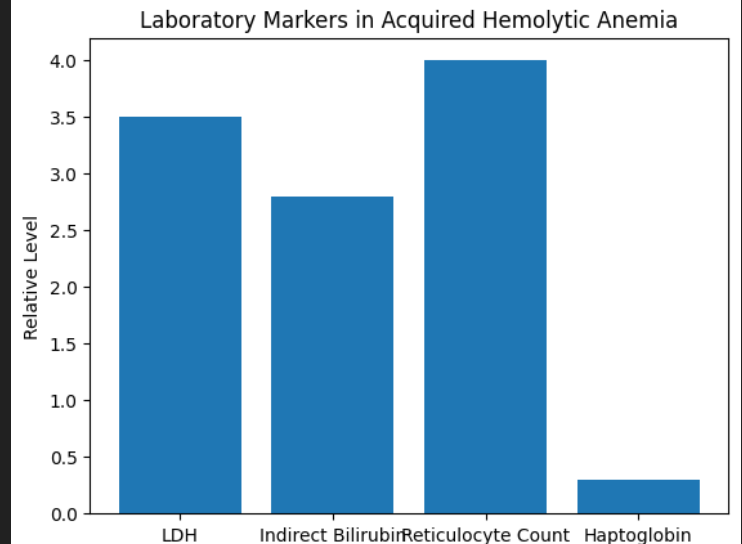

Diagnostic Evaluation

8.1 Laboratory Markers of Hemolysis

Reticulocytosis (unless marrow suppressed)

Elevated indirect bilirubin

Increased LDH

Reduced haptoglobin

8.2 Immunohematologic Tests

Direct antiglobulin test (DAT)

IgG positive

C3d positive

Indirect antiglobulin test (selected cases)

Management Strategies

10.1 Emergency Management

Stabilization (ABC)

Oxygen therapy

Packed RBC transfusion (cross‑match challenges anticipated)

10.2 Pharmacologic Therapy

First‑line:

Corticosteroids (prednisolone 2–4 mg/kg/day)

Second‑line:

IVIG

Rituximab

Third‑line / Refractory:

Immunosuppressants

Splenectomy (carefully selected cases)

Special Situations

11.1 Acquired Hemolytic Anemia in Infancy

Often post‑viral

Higher risk of rapid decompensation

Usually good response to steroids

11.2 Hemolysis in Autoimmune Diseases

SLE‑associated AIHA

Evans syndrome (AIHA + ITP)

Complications

Pigment gallstones

Chronic anemia

Iron overload (repeated transfusions)

Thromboembolism

Infections due to immunosuppression

Prognosis and Outcomes

Primary AIHA: good prognosis, high remission rates

Secondary AIHA: relapse common

Mortality is low with modern therapy but increases with delayed diagnosis

Prevention and Follow‑Up

Vaccination against encapsulated organisms

Infection prevention

Long‑term monitoring for relapse

Conclusion

Acquired hemolytic anemia in children is a multifaceted disorder requiring a thorough understanding of immunologic mechanisms, vigilant diagnostic evaluation, and individualized therapy. Advances in immunomodulatory treatment have significantly improved outcomes. Early recognition and multidisciplinary care remain the cornerstone of successful management.

REFERENCES

Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM.

Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2020.

Chapter: Hemolytic Anemias in Children.Orkin SH, Fisher DE, Ginsburg D, Look AT, Lux SE, Nathan DG. Nathan and Oski’s Hematology and Oncology of Infancy and Childhood. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2015.

Hoffbrand AV, Higgs DR, Keeling DM, Mehta AB. Postgraduate Hematology. 7th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2016.

Greer JP, Arber DA, Glader B, et al. Wintrobe’s Clinical Hematology. 14th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2019.

Hill QA, Stamps R, Massey E, Grainger JD, Provan D, Hill A. The diagnosis and management of primary autoimmune hemolytic anemia. British Journal of Haematology. 2017;176(3):395–411.

Michel M. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015(1):387–396.

Ware RE, de Montalembert M, Tshilolo L, Abboud MR. Hemolytic anemias in children.

The Lancet. 2017;390(10091):311–323.Sokol RJ, Booker DJ, Stamps R. Autoimmune hemolysis: an 18-year study of 865 cases referred to a regional transfusion center. British Medical Journal. 1992;305:156–159.

Rothman JA, Weitz IC. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in children.

Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2013;60(6):1489–1511.Teachey DT, Manno CS. Autoimmune cytopenias in childhood. Seminars in Hematology. 2005;42(4):299–310.

Barcellini W, Fattizzo B. Clinical applications of hemolytic markers in autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

Disease Markers. 2015;2015:635670.