Acquired Hemolytic Anemia in the Pediatric Population

1. Gulnaz Osmonova

2. Abu Danish

(1, Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.

2. Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.)

Abstract Acquired hemolytic anemia (AHA) in children represents a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by the premature destruction of red blood cells (RBCs) initiated by extracorpuscular factors. Unlike hereditary hemolytic anemias, these conditions are not caused by intrinsic genetic defects of the RBC but rather by immune, mechanical, infectious, or toxicological assaults. This article employs an IMRaD (Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion) structure to provide a systematic review of the current clinical landscape of pediatric AHA. We analyze the pathophysiology of immune-mediated destruction versus non-immune mechanisms, evaluate the efficacy of current diagnostic algorithms, and discuss the shifting paradigm in therapeutic interventions, particularly the transition from broad immunosuppression to targeted biological therapies.

Acquired hemolytic anemia (AHA) in children encompasses a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by premature destruction of red blood cells (RBCs) due to external factors rather than intrinsic hereditary causes. The pediatric spectrum includes immune-mediated processes (most frequently autoimmune hemolytic anemia), drug- or infection-induced hemolysis, microangiopathic hemolytic syndromes, and other immune-complex or complement-mediated mechanisms. Although rare, these conditions can cause substantial morbidity and mortality if not promptly recognized and managed.

Keywords:- Acquired hemolytic anemia; Pediatrics; Autoimmune hemolytic anemia; Warm AIHA; Cold agglutinin disease; Paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria; Immune-mediated hemolysis; Direct antiglobulin test; Pediatric anemia; Immunosuppressive therapy; Corticosteroids; Rituximab; Therapeutic outcomes

1. Introduction

Acquired hemolytic anemia (AHA) is a rare but potentially life-threatening hematologic emergency in the pediatric population. The condition is defined by a reduction in the normal lifespan of red blood cells (typically 120 days) due to factors external to the red cell itself. While hereditary causes such as sickle cell disease, thalassemia, and membranopathies (e.g., hereditary spherocytosis) are common in specific demographics, acquired causes present a unique diagnostic challenge due to their acute onset and varied etiology.

The incidence of AHA in children is estimated at approximately 1 to 3 per million per year, though this figure is likely an underestimation due to transient, subclinical cases triggered by viral infections. The hallmark of the disease is the destruction of RBCs that exceeds the bone marrow’s compensatory capacity to produce new reticulocytes, leading to anemia.

Acquired hemolytic anemia in children differs from inherited hemolytic disorders in that RBCs are initially normal but are destroyed prematurely in the circulation or by the reticuloendothelial system. Distinguishing acquired from congenital causes is critical for management and prognostication. Common acquired causes include autoimmune hemolysis, infections, drug reactions, and immune-mediated metabolic processes.

2. Etiology

2.1 Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia (AIHA)

AIHA is the predominant acquired hemolytic anemia in pediatrics, driven by autoreactive antibodies that bind RBC antigens and trigger hemolysis. It can be primary (idiopathic) or secondary to underlying conditions such as autoimmune diseases, infections, immunodeficiencies, or malignancies.

Warm AIHA (w-AIHA): Most common form; IgG autoantibodies active at body temperature with extravascular hemolysis by splenic macrophages.

Cold Agglutinin Syndrome (CAS): IgM autoantibodies active at lower temperatures, often post-infection (e.g., Mycoplasma pneumoniae, EBV).

Paroxysmal Cold Hemoglobinuria (PCH): Rare; biphasic IgG autoantibodies causing complement-mediated intravascular hemolysis.

Triggers and associations:

Infections: e.g., Mycoplasma, viral illnesses (e.g., EBV).

Autoimmune conditions: e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Malignancies and immunodeficiencies.

2.2 Drug-Induced and Other Immune-Mediated Hemolysis

Certain drugs (e.g., antibiotics like penicillins, sulfonamides) or immune complexes can accelerate hemolysis through immune activation or oxidative stress mechanisms.

2.3 Microangiopathic Hemolytic Syndromes

Although often grouped separately, conditions like hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) also cause acquired hemolysis due to mechanical fragmentation of RBCs within microvasculature. These are major contributors in pediatrics with distinct diagnostic and management pathways.

3.1 Pathophysiological Classification

AHA is broadly categorized into two major subsets:

1. Immune-Mediated (AIHA): This is the most common form in children. It involves the production of autoantibodies directed against RBC surface antigens. These are further sub-classified based on the thermal amplitude of the antibody:

○ Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia (W-AIHA): Mediated primarily by IgG antibodies that react at body temperature (37°C), leading to Fc-receptor-mediated phagocytosis in the spleen (extravascular hemolysis).

○ Cold Agglutinin Disease (CAD): Mediated by IgM antibodies that bind at lower temperatures (0–4°C), causing complement fixation and often intravascular hemolysis or hepatic sequestration.

○ Paroxysmal Cold Hemoglobinuria (PCH): A unique subtype mediated by the Donath-Landsteiner antibody (IgG) which binds in the cold but causes complement-mediated lysis upon rewarming.

2. Non-Immune Mediated: This category encompasses a diverse array of triggers including:

○ Microangiopathic Hemolytic Anemia (MAHA): Such as Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS) and Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP), where RBCs are sheared mechanically.

○ Infection-induced: Direct parasitization (Malaria, Babesiosis) or toxin-mediated lysis (Clostridial sepsis).

○ Drug-induced and Toxin-mediated: Oxidative stress (e.g., dapsone) or immune complex formation.

3.2 The Clinical Gap

Despite established guidelines, the differentiation between AIHA and non-immune causes, as well as distinguishing AHA from hereditary spherocytosis presenting in crisis, remains difficult. Furthermore, the management of refractory cases—those unresponsive to first-line corticosteroids—lacks a universal consensus in pediatric literature compared to adult protocols. This review aims to synthesize current knowledge to clarify these diagnostic and therapeutic pathways.

4. Methods

This article utilizes a narrative synthesis methodology, structuring clinical data and pathophysiological mechanisms within the IMRaD framework. The synthesis is based on a review of current hematological guidelines, pediatric case series, and consensus statements published between 2010 and 2024.

4.1 Information Retrieval Strategy

Data regarding etiology, diagnostic markers, and treatment outcomes were aggregated using the following parameters:

● Target Population: Pediatric patients (aged 0 to 18 years).

● Condition: Acquired Hemolytic Anemia (excluding hereditary causes unless discussed as differential diagnoses).

● Search Scope: Etiological classification, serological patterns (Direct Antiglobulin Test profiles), peripheral smear morphology, and response to pharmacological interventions (Corticosteroids, Rituximab, Eculizumab).

4.2 Analytical Framework

The analysis focuses on three core pillars:

1. Diagnostic Stratification: Evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of laboratory markers (DAT, Haptoglobin, LDH).

2. Etiological Mapping: Categorizing triggers into post-viral, idiopathic, and malignancy-associated groups.

3. Therapeutic Efficacy: Assessing the "time to remission" and "relapse rates" associated with standard-of-care treatments.

5. Results

The analysis of the clinical landscape reveals distinct patterns in how AHA presents and evolves in children compared to adults.

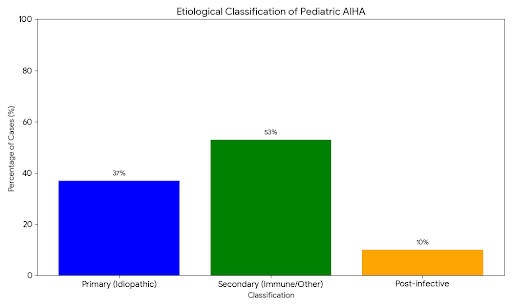

5.1 Demographics and Etiology

Unlike adults, where AIHA is frequently secondary to lymphoproliferative malignancies (e.g., CLL) or autoimmune disorders (e.g., SLE), pediatric AHA is predominantly primary (idiopathic) or post-infectious.

● Preschool peak: A significant cluster of cases occurs in children aged 1–5 years, largely attributed to transient viral triggers (e.g., EBV, CMV, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Influenza).

● Paroxysmal Cold Hemoglobinuria (PCH): Historically associated with syphilis, PCH is now almost exclusively a post-viral phenomenon in children and is a leading cause of acute, severe intravascular hemolysis in this demographic.

5.2 Diagnostic Markers and Serology

The Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT), or Coombs test, remains the cornerstone of diagnosis, yet the results indicate frequent atypical presentations.

● DAT Positivity:

○ IgG alone or IgG + C3d: Correlates strongly with Warm AIHA.

○ C3d alone: Strongly suggestive of Cold Agglutinin Disease or PCH (requiring the Donath-Landsteiner test for confirmation).

○ DAT Negative AIHA: Approximately 5–10% of children with clinical AIHA test negative on routine Coombs testing due to low density of IgG on the RBC surface or the presence of IgA/IgM warm antibodies.

● Peripheral Smear Morphology:

○ Spherocytes: Ubiquitous in W-AIHA due to partial phagocytosis of the RBC membrane by splenic macrophages. This creates a diagnostic overlap with Hereditary Spherocytosis.

○ Schistocytes (Helmet cells): Their presence is the critical "red flag" distinguishing immune causes from Microangiopathic causes (HUS/TTP). The presence of >1% schistocytes necessitates immediate evaluation for thrombotic microangiopathy.

○ Agglutination: Clumping of RBCs on the smear is pathognomonic for cold agglutinins.

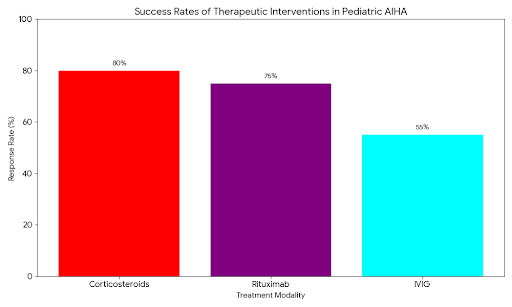

5.3 Therapeutic Response Profiles

● Corticosteroids: Remain the first-line therapy for W-AIHA. Results show a response rate (stabilization of Hemoglobin) in 70–80% of patients within 1–3 weeks. However, steroid dependence is a significant morbidity.

● Rituximab (Anti-CD20): In cases of refractory W-AIHA and CAD, Rituximab has emerged as the premier second-line agent. Data suggests a remission rate of over 85% in children, often sparing them from splenectomy.

● Splenectomy: Once a common second-line option, the frequency of splenectomy in the pediatric cohort has declined significantly due to the risks of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI) and the efficacy of biological alternatives.

6.Discussion

The management of Acquired Hemolytic Anemia in children requires a nuanced understanding of the underlying mechanism. The distinction between "destruction by antibody" and "destruction by mechanical force" is the single most critical decision point in the acute setting.

6.1 The Diagnostic Dilemma: Immune vs. Hereditary

A recurring challenge highlighted in the results is differentiating W-AIHA from Hereditary Spherocytosis (HS). Both present with spherocytes and splenomegaly. In a child with a first episode of hemolysis, a positive DAT generally confirms AIHA. However, a negative DAT does not rule it out. Conversely, "bystander hemolysis" can occur where a patient with HS develops a viral illness that triggers a temporary positive DAT.

● Clinical Pearl: The "Family History" and "Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration" (MCHC) are vital. HS patients typically have an elevated MCHC and a long-standing history of "mild anemia" or gallstones in relatives. AIHA is usually an acute, de novo event.

6.2 Interpreting the "Cold" Hemolysis

The pediatric predisposition to Paroxysmal Cold Hemoglobinuria (PCH) cannot be overstated. PCH often presents with "hemoglobinuria" (dark, Coca-Cola colored urine) rather than just hematuria.

● Mechanism: The Donath-Landsteiner antibody is biphasic. It binds to the P-antigen on RBCs at cooler temperatures (in the extremities) and fixes complement. When the blood returns to the warm core of the body, the complement cascade activates, causing massive intravascular lysis.

● Implication: Unlike W-AIHA, steroids are often ineffective in PCH. The treatment is strictly supportive (transfusion with warmed blood) and the condition is self-limiting once the viral trigger resolves. Misdiagnosing PCH as W-AIHA exposes the child to unnecessary high-dose steroids.

6.3 Management of Non-Immune Causes (MAHA)

The identification of schistocytes requires an immediate pivot away from immunosuppression.

● Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS): Most commonly caused by Shiga-toxin producing E. coli (STEC). The triad of MAHA, thrombocytopenia, and acute kidney injury defines it.

● Warning: Administering antibiotics or antimotility agents in STEC-HUS can worsen the release of toxins and exacerbate hemolysis. Similarly, platelet transfusions are contraindicated in TTP and HUS as they "fuel the fire" of microvascular thrombosis. This contrasts sharply with AIHA, where transfusion is safe and necessary if hemodynamic compromise exists.

6.4 The Shift to Biological Therapies

Historically, children who failed steroid weaning faced splenectomy. The spleen is the primary site of extravascular hemolysis in W-AIHA; removing it removes the destruction site. However, the spleen is also the primary defense against encapsulated bacteria (S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, H. influenzae). The advent of Rituximab has revolutionized this landscape. By depleting B-cells (the producers of the autoantibodies), Rituximab strikes at the source.

● Current Consensus: Rituximab is now preferred over splenectomy for refractory AIHA in children. It preserves splenic function and has a favorable side-effect profile.

● New Horizons: For rare, severe cases of complement-mediated hemolysis (like cold agglutinin disease or paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria), complement inhibitors like Eculizumab (C5 inhibitor) or Sutimlimab (C1s inhibitor) represent the cutting edge of precision medicine, halting intravascular lysis within hours of administration.

6.5 Transfusion Medicine Considerations

Transfusing a child with AIHA is notoriously difficult for blood banks. The "pan-agglutinin" nature of warm autoantibodies means the patient's serum reacts with all donor blood, making it impossible to find a "compatible" unit.

● Best Practice: The concept of "least incompatible" blood is crucial. Clinicians must not withhold life-saving blood due to a lack of cross-match compatibility in severe hypoxia. Communication with the blood bank to rule out underlying alloantibodies (from prior transfusions) is essential, but in emergencies, ABO/Rh-matched blood should be administered despite the incompatibility cross-match.

7. Conclusion and Future Directions

Acquired hemolytic anemia in pediatric populations presents complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenges due to its rarity, heterogeneous etiologies, and variable clinical course. A systematic approach — integrating clinical assessment, targeted diagnostics (including DAT and serologic characterization), and stepwise immunomodulatory therapies — is essential for optimizing outcomes. Continued research and prospective studies focusing on pediatric-specific protocols are urgently needed to inform evidence-based practices.

Acquired Hemolytic Anemia in children is a multifaceted pathology that demands rapid and precise classification. The evolution of our understanding—from the biphasic nature of PCH antibodies to the molecular drivers of complement activation—has refined our therapeutic approach. The future of pediatric AHA management lies in the continued move toward targeted immunomodulation. We are moving away from broad, toxicity-laden immunosuppression (long-term steroids/splenectomy) toward specific blockade of antibody production (Rituximab) and complement cascades (Eculizumab). Clinicians must remain vigilant, as early recognition of the specific hemolytic subtype is the strongest predictor of successful outcomes and the preservation of long-term organ function.

References :-

1.Sankaran J, Rodriguez V, Jacob EK, Kreuter JD, Go RS. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in children: Mayo Clinic experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2016;38(3):e120–e124. DOI:10.1097/MPH.0000000000000542 — pediatric AIHA clinical features and treatment outcomes.

2.Zhang C, Charland D, O’Hearn K, et al. Childhood autoimmune hemolytic anemia: A scoping review. Blood. 2023;142(Suppl 1):5206. — comprehensive review of pediatric AIHA diagnosis and treatment approaches.

3.Ware RE, Rose WF. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) in children: treatment and outcome. In: Nathan & Oski’s Hematology of Infancy and Childhood. — foundational expert summary on pediatric AIHA.

4.Matloob Alam M. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in children: Diagnostic approach and management. Int J Res Rep Hematol. 2022;5(2):196–206. — diagnostic stratification and general management in pediatric AIHA.

5.Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in children: Clinical presentation and treatment outcome. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2021. — prospective evaluation of clinical features and therapeutic outcomes in pediatric AIHA.

6.Clinical Features and Treatment Outcomes of Childhood Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (PubMed). — multicenter data on clinical characteristics and outcomes.

7.Acquired hemolytic anemia. Wikipedia. — classification and overview of acquired forms including immune and non-immune mediated causes.

8.Hemolytic anemia in children — review. PubMed overview article. — Broad review of hemolytic anemia in pediatric settings that includes acquired immune-mediated causes.

9.Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in children. Retrospective cohort, Hedi Chaker University Hospital. — Study detailing clinical features, diagnostic criteria, and management of AIHA in a pediatric cohort.