A Comprehensive Review of Acute Bacterial Cholangitis

1. Dr. Turdaliev S.O.

2. Aditya Borbale

Om Ratnaparkhi

(1. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic

2. Students, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.)

Abstract

Acute bacterial cholangitis is a potentially life-threatening infection of the biliary tree, fundamentally predicated on the dual pathology of biliary obstruction and subsequent bacterial proliferation.1 The clinical spectrum of this condition is broad, ranging from mild, self-limiting disease to fulminant septic shock with multi-organ failure, carrying a significant mortality rate that can approach 15% despite advances in antimicrobial therapy and interventional procedures.1 The Tokyo Guidelines, particularly the 2018 revision (TG18), have emerged as the global standard for the diagnosis, severity stratification, and management of acute cholangitis, providing a crucial framework for clinical decision-making.4 The cornerstones of effective treatment are twofold and time-sensitive: the prompt administration of systemic antimicrobial therapy to control bacteremia and urgent biliary drainage to achieve definitive source control by relieving the underlying obstruction.7 The management of this condition is increasingly complicated by the global rise of antimicrobial resistance, which poses a significant and growing threat to the efficacy of established empiric treatment protocols.1 This review provides a comprehensive overview of the current understanding of acute bacterial cholangitis, synthesizing evidence on its pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management, with a focus on evidence-based guidelines and emerging challenges.

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Definition and Historical Context

Acute bacterial cholangitis, historically termed ascending cholangitis, is an acute inflammatory and infectious process within the intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic bile duct system.1 It represents a true medical and surgical emergency, capable of rapid clinical deterioration if not promptly diagnosed and treated.1 The conceptual foundation of this disease was laid in 1877 when Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot first described "hepatic fever," establishing the classic clinical triad of intermittent fever with chills, right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal pain, and jaundice.3 For decades, this triad served as the primary diagnostic hallmark of the condition.

The understanding of the disease's severity spectrum evolved significantly in 1959 when Reynolds and Dargan expanded upon Charcot's description. They observed that a subset of patients presented with two additional, ominous signs: altered mental status (lethargy or confusion) and shock (hypotension). This constellation, now known as the Reynolds' pentad, was recognized as indicative of a more severe, suppurative form of the disease with progression to biliary sepsis and a dire prognosis, for which they advocated emergent surgical decompression as the only effective treatment.3

This historical progression in clinical description is not merely an academic footnote but a direct reflection of the underlying pathophysiological cascade of the disease. The signs described by Charcot—fever from infection, pain from biliary distension and inflammation, and jaundice from obstruction—represent the consequences of a primarily localized process within the biliary tree.3 The additional signs identified by Reynolds—neurological dysfunction and cardiovascular collapse—are the systemic manifestations of uncontrolled infection and the host's dysregulated inflammatory response, hallmarks of sepsis and organ failure.3 This conceptual leap from a triad to a pentad mirrors the modern understanding of the disease's potential to progress from a contained biliary infection to a systemic, life-threatening crisis. This progression is now formally codified in the Tokyo Guidelines' severity grading system, where the presence of organ dysfunction, the very essence of Reynolds' pentad, defines the most severe grade of cholangitis, which demands the most urgent and aggressive interventions.4

1.2 The Clinical Significance and Epidemiology of Acute Cholangitis

Acute cholangitis carries substantial clinical significance due to its potential for high morbidity and mortality. It remains the second and third most common cause of community-acquired and hospital-acquired bacteremia, respectively, underscoring its role as a major source of systemic infection.1 While considered a relatively uncommon condition in the United States, with fewer than 200,000 cases reported annually, its incidence is intrinsically linked to the high prevalence of gallstone disease.2 Studies indicate that 6% to 9% of patients hospitalized with gallstone-related complications are diagnosed with acute cholangitis.2

The disease typically affects individuals in their 50s and 60s, with a nearly equal distribution between males and females.2 The prevalence of the primary risk factor, cholelithiasis, varies significantly among different ethnicities, being highest in Native American (60-70%) and Hispanic populations and lower in Asian and African American populations, which indirectly influences the demographic patterns of cholangitis.2 Despite significant advances in critical care, antibiotic therapy, and minimally invasive drainage techniques, the mortality rate for acute cholangitis remains formidable, with various reports citing rates of up to 15%.1 This persistent mortality risk highlights the critical importance of early recognition, accurate risk stratification, and timely, aggressive treatment.2

1.3 Core Pathophysiology: The Interplay of Biliary Obstruction and Infection

The pathogenesis of acute cholangitis is classically understood through a "two-hit" model, which requires the coexistence of two fundamental factors: biliary stasis, typically caused by obstruction, and the presence of bacteria in the bile (bacterobilia).1 Under normal physiological conditions, the biliary tree is sterile. This sterility is actively maintained by several defense mechanisms, including the continuous antegrade flow of bile, which has a mechanical flushing effect; the bacteriostatic properties of bile salts; and local immune defenses, such as the secretion of immunoglobulin A (IgA) by the biliary epithelium.2 The sphincter of Oddi also acts as a mechanical barrier, preventing reflux of duodenal contents into the biliary system.18 Acute cholangitis develops when these defense mechanisms are compromised.

1.3.1 The Role of Intraductal Pressure and Cholangiovenous Reflux

Biliary obstruction is the critical initiating event. It leads to the stagnation of bile, creating a fertile culture medium for bacterial proliferation.2 As bacteria multiply, the resulting inflammation and accumulation of purulent material cause a rapid increase in intraductal pressure. Normal pressure within the common bile duct is approximately 7-14 cm H2O.4 When obstruction causes this pressure to rise above a critical threshold, determined to be greater than 20 cm, the structural integrity of the biliary system is compromised.4 The tight junctions between cholangiocytes (the cells lining the bile ducts) widen, and the permeability of the acutely inflamed biliary epithelium increases.2 This breach allows for the direct translocation of bacteria and their toxic byproducts (endotoxins) from the bile ducts into the systemic circulation via the hepatic sinusoids and peri-biliary lymphatic channels. This process, known as cholangiovenous and cholangiolymphatic reflux, is the pivotal event that transforms a localized biliary infection into systemic bacteremia and sepsis.4

The development of severe cholangitis can be conceptualized not merely as the result of two independent factors but as a vicious, self-amplifying cycle. The initial mechanical obstruction provides the static environment essential for significant bacterial growth. This biological proliferation then fuels an intense inflammatory response, which causes further edema and increases intraductal pressure, thereby exacerbating the mechanical component of the disease. This heightened pressure facilitates greater systemic translocation of bacteria and endotoxins, which in turn drives the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and progression to septic shock. This feedback loop, where the biological consequence (infection) amplifies the systemic impact of the mechanical problem (high pressure), explains why effective management must simultaneously and urgently address both components. Antibiotics are required to control the biological process of infection, while biliary drainage is essential to break the mechanical cycle of high pressure and ongoing systemic seeding.1

1.3.2 Bacteriology of the Biliary Tract

The bacteria responsible for acute cholangitis are typically enteric organisms that ascend from the duodenum into the biliary tree, a process facilitated by the compromised sphincter of Oddi or other anatomical abnormalities.2 In rare instances, bacteria can also reach the bile via hematogenous spread from the portal vein.2 While bile cultures in healthy individuals are sterile, they are positive in over 70% of patients with acute cholangitis.3

The microbial profile is most commonly dominated by Gram-negative aerobes. The most frequently isolated pathogens include Escherichia coli (found in 25-50% of cases), Klebsiella species (15-20%), and Enterobacter species (5-10%).2 Gram-positive organisms, particularly Enterococcus species, are also common, identified in 10-20% of cases.2 Anaerobic bacteria, such as Bacteroides and Clostridium species, are involved in approximately 15% of infections, and their prevalence increases in patients with a history of biliary-enteric anastomosis, severe disease, or advanced age.19 Infections are often polymicrobial, involving multiple bacterial species, which complicates empiric antibiotic selection.19 The specific bacteriology can also be influenced by whether the infection is community-acquired versus healthcare-associated, with the latter being more likely to involve resistant organisms.8

2.0 Classification of Acute Cholangitis

2.1 Overview of Cholangiopathies

To accurately contextualize acute bacterial cholangitis, it is essential to differentiate it from other, primarily chronic and non-infectious, forms of biliary tract inflammation, collectively known as cholangiopathies. While acute bacterial cholangitis is an infectious emergency driven by obstruction, other conditions cause chronic inflammation that can lead to fibrosis, stricture formation, and ultimately, biliary cirrhosis.2 These chronic conditions, by virtue of causing strictures and impairing bile flow, can create a predisposition to recurrent episodes of acute bacterial cholangitis. Key distinct entities include:

● Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC): An autoimmune disease characterized by the progressive destruction of small intrahepatic bile ducts. It is strongly associated with the presence of antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) and predominantly affects middle-aged women.24

● Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC): A chronic, progressive disease of unknown etiology characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of both intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, leading to multifocal strictures. It is strongly associated with inflammatory bowel disease, particularly ulcerative colitis.2

● IgG4-Related Cholangitis: A fibroinflammatory condition that is a manifestation of a systemic disease known as IgG4-related disease. It often mimics PSC or cholangiocarcinoma but is characterized by elevated serum IgG4 levels and a dramatic response to corticosteroid therapy.2

● Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis (Oriental Cholangiohepatitis): Characterized by recurrent episodes of bacterial cholangitis associated with the formation of intrahepatic pigment stones and biliary strictures. It is more prevalent in East Asia and is linked to parasitic infestations and nutritional factors.2

2.2 The Tokyo Guidelines (TG18) Severity Grading System

The management of acute cholangitis was revolutionized by the development of the Tokyo Guidelines (TG), first introduced in 2007 and subsequently updated in 2013 and 2018. The TG18 severity grading system is now the globally accepted standard for the initial risk stratification and management of patients with acute cholangitis.4 This system is designed for rapid, objective assessment at the time of diagnosis and should be reassessed frequently (e.g., at 24 and 48 hours) to monitor the patient's response to treatment and detect any clinical deterioration.31

The TG18 grading system is fundamentally more than a simple prognostic tool; it functions as a prescriptive clinical algorithm that directly links a patient's physiological status to a specific, time-sensitive management pathway. The classification of a patient into one of three grades is not an academic exercise but an immediate and clear directive for the clinician regarding the necessity and, critically, the urgency of biliary drainage. For example, a diagnosis of Grade II (Moderate) disease is a direct indication for "early" biliary drainage, defined as within 48 hours, while a diagnosis of Grade III (Severe) disease mandates "urgent" drainage, typically within 24 hours, after initial hemodynamic stabilization.5 This transforms the classification from a passive descriptor of severity into an active, indispensable tool for clinical decision-making and resource allocation, effectively serving as a triage system at the patient's bedside.

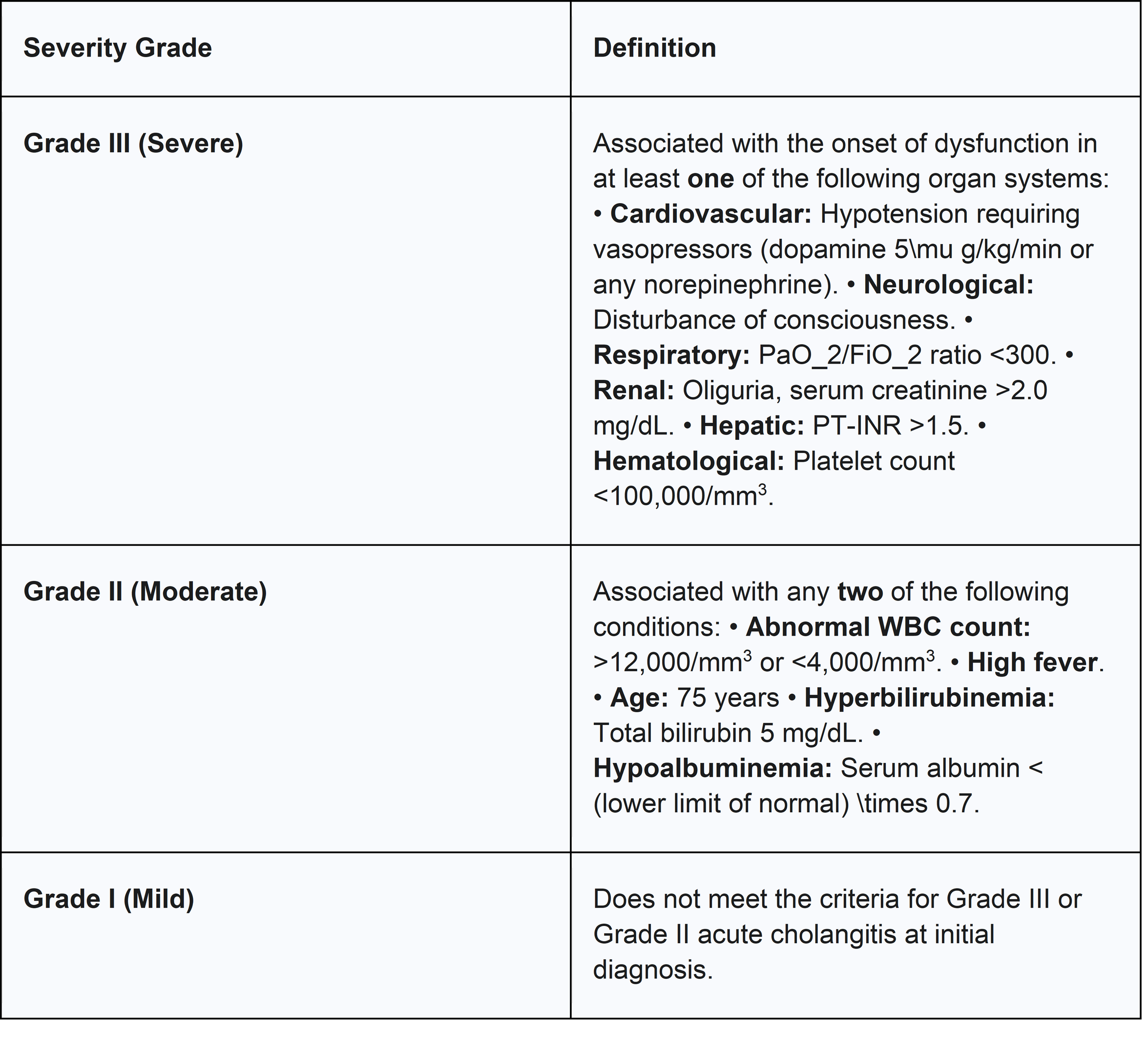

The TG18 system stratifies patients into three grades of severity:

2.2.1 Grade I (Mild) Acute Cholangitis

This is defined by exclusion, applying to patients with a definite diagnosis of acute cholangitis who do not meet the criteria for either Grade II or Grade III disease at the time of initial assessment.4 These patients typically present without signs of organ dysfunction or significant systemic inflammation. The majority of individuals with Grade I cholangitis respond favorably to initial medical management, which consists of intravenous fluids and appropriate antibiotic therapy, and do not require immediate biliary drainage.5

2.2.2 Grade II (Moderate) Acute Cholangitis

This grade identifies patients who are at an increased risk of progressing to severe disease and who require prompt intervention. It is defined by the presence of a definite diagnosis of acute cholangitis accompanied by any two of the following five conditions 4:

● Abnormal White Blood Cell (WBC) count: >12,000/mm3 or <4,000/mm3

● High fever: 39° C (102.2° F)

● Advanced age: 75 years

● Hyperbilirubinemia: Total bilirubin 5 mg/dL

● Hypoalbuminemia: Serum albumin less than the standard lower limit 0.7

Patients meeting these criteria are considered to have a more significant systemic inflammatory response and are candidates for early biliary drainage to prevent deterioration.5

2.2.3 Grade III (Severe) Acute Cholangitis

This is the most critical category, representing life-threatening biliary sepsis with established organ dysfunction. It is defined by a definite diagnosis of acute cholangitis accompanied by dysfunction in at least one of the following six organ systems 4:

● Cardiovascular dysfunction: Hypotension requiring treatment with a vasopressor (e.g., dopamine or any dose of norepinephrine).

● Neurological dysfunction: Disturbance of consciousness.

● Respiratory dysfunction: PaO_2/FiO_2 ratio <300.

● Renal dysfunction: Oliguria or serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dL.

● Hepatic dysfunction: Prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (PT-INR) >1.5.

● Hematological dysfunction: Platelet count <100,000/mm3.

These patients require immediate admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) for aggressive resuscitation and organ support, followed by urgent biliary drainage as soon as they are hemodynamically stable enough to tolerate a procedure.

Table 1: Tokyo Guidelines 2018 (TG18) Severity Grading Criteria for Acute Cholangitis

3.0 Causes and Risk Factors

The etiology of acute bacterial cholangitis is best conceptualized as a multi-tiered causal chain. At the most immediate level (Tier 1) are the direct causes of biliary obstruction, such as stones or strictures. These are, in turn, caused by underlying conditions and behaviors (Tier 2), like metabolic syndromes predisposing to gallstones or autoimmune diseases causing strictures. Finally, at the foundational level (Tier 3), are the fundamental genetic, environmental, and demographic predispositions that increase an individual's susceptibility to the conditions in the preceding tiers. This framework provides a logical structure for a comprehensive exploration of all contributing factors, from the molecular to the societal level.

3.1 Genetic and Familial Predispositions

While acute bacterial cholangitis itself is not a primary genetic disorder, a significant genetic component exists for many of the underlying conditions that predispose an individual to biliary obstruction.

● Autoimmune Cholangiopathies: Conditions such as Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC) and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC), which lead to chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and biliary strictures, have a well-established genetic basis. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified numerous susceptibility loci, both within the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex and in non-HLA genes, that are involved in immune regulation.36 A family history of PBC is a strong risk factor, indicating a clear heritable component.25 These genetic predispositions do not directly cause bacterial cholangitis but create the anatomical substrate (strictures) for recurrent biliary stasis and infection.

● Cholelithiasis: The most common precursor to acute cholangitis, gallstone disease, also has a significant genetic and ethnic predisposition. The prevalence of cholesterol gallstones is markedly higher in certain ethnic groups, such as Native Americans and Hispanics, compared to Caucasian, Asian, or African American populations, pointing to a strong influence of genetic factors on bile composition and gallbladder motility.1

3.2 Maternal Factors

Pregnancy introduces a unique physiological state characterized by profound hormonal changes that can impact the hepatobiliary system. While bacterial cholangitis during pregnancy is rare, conditions related to cholestasis are more common and provide a relevant model for understanding the impact of impaired bile flow.

● Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy (ICP): This is a pregnancy-specific liver disorder characterized by pruritus and elevated serum bile acids, typically occurring in the third trimester when hormone concentrations are highest.39 While distinct from obstructive cholangitis, ICP represents a state of hormonally-induced cholestasis that shares a key pathophysiological element: impaired bile flow.23 Risk factors for ICP include a genetic predisposition (with several identified gene mutations), carrying multiples, and IVF treatment.39 ICP is associated with significant fetal risks, including preterm labor, meconium passage, and stillbirth, with the risk correlating directly with the degree of bile acid elevation.39

● Pregnancy and Chronic Cholangiopathies: For women with pre-existing chronic liver diseases like PBC or PSC, pregnancy can be a period of risk. The high-estrogen state of pregnancy can exacerbate cholestasis.26 Studies have shown that women with PBC may be at increased risk for disease flares in the postpartum period.41 Similarly, patients with PSC can experience a worsening of liver-related symptoms during pregnancy, and this subgroup may have a poorer long-term prognosis.27

3.3 Environmental and Lifestyle Factors

Environmental exposures and lifestyle choices contribute significantly to the risk of developing conditions that lead to biliary obstruction.

●Triggers for Autoimmune Cholangiopathies: The development of PBC is thought to be triggered by environmental factors in genetically susceptible individuals. Case-control studies have identified several potential environmental risk factors, including poor environmental hygiene in childhood (e.g., use of vault toilets, living near unpaved roads), a history of urinary tract infections, and chronic exposure to chemicals through tobacco smoking and the use of hair dyes.38 These factors are hypothesized to trigger the loss of immune tolerance that initiates the autoimmune process.43

● Risk Factors for Cholelithiasis: Lifestyle factors play a major role in the formation of cholesterol gallstones, the most common cause of acute cholangitis. These modifiable risk factors include high-fat (triglyceride) intake, sedentary lifestyles, obesity, and periods of rapid weight loss (e.g., after bariatric surgery).2 Heavy alcohol consumption can lead to liver cirrhosis, which is also a risk factor for gallstone formation.2

3.4 Other Predisposing Factors and Etiologies

This category encompasses the direct, proximate causes of biliary obstruction that precipitate an episode of acute bacterial cholangitis.

3.4.1 Choledocholithiasis: The Primary Cause

The most frequent cause of biliary obstruction leading to acute cholangitis is the presence of gallstones within the common bile duct (CBD), a condition known as choledocholithiasis.2 In various case series, choledocholithiasis accounts for up to 85% of all cases of acute cholangitis.17 These stones can be classified as:

● Secondary stones: The vast majority of CBD stones are secondary, having formed in the gallbladder and subsequently migrated into the common bile duct.46

● Primary stones: These are less common and form de novo within the bile ducts themselves, often in the setting of chronic stasis, strictures, or infection (e.g., in recurrent pyogenic cholangitis).47

3.4.2 Benign and Malignant Biliary Strictures

Stenosis or narrowing of the bile duct is another major cause of obstruction. These strictures can be either benign or malignant and are reported to account for 10-30% of acute cholangitis cases.2

● Benign Strictures: These can result from postoperative injury (e.g., after cholecystectomy), chronic pancreatitis, or inflammatory conditions like PSC.2

● Malignant Strictures: Obstruction can be caused by tumors arising from the biliary tree itself (cholangiocarcinoma) or by external compression from adjacent malignancies, most commonly pancreatic head cancer, ampullary cancer, or metastatic disease to the porta hepatis.2 Malignant biliary obstruction often presents with painless jaundice, but can be complicated by cholangitis, particularly after instrumentation.48

3.4.3 Iatrogenic Causes: Post-ERCP Cholangitis

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) presents a clinical paradox. It is the primary and most effective therapeutic modality for relieving biliary obstruction and treating cholangitis, yet it is also a significant iatrogenic cause of the condition, with post-ERCP cholangitis occurring in 0.5% to 2.4% of procedures, and potentially higher in certain risk groups.2 This paradox highlights that the benefit of the procedure is entirely contingent on achieving complete and adequate drainage of the biliary system. When drainage is incomplete or fails, the intervention can convert a stable obstruction into an acute emergency. The procedure introduces bacteria from the duodenum into the biliary tree and can increase intraductal pressure through contrast injection; without providing an effective and lasting outlet for bile flow, this combination creates the perfect storm for fulminant cholangitis.4 This underscores the critical importance of procedural expertise, appropriate patient selection, and an unwavering focus on the ultimate goal of achieving definitive source control. Key risk factors for developing post-ERCP cholangitis include:

● Incomplete or failed biliary drainage: This is the most significant risk factor. One study reported that acute cholangitis occurred in 75% of patients who had retained stones and failed drainage, compared to only 3% with successful drainage.50

● Stent placement in malignant strictures: Stents placed across malignant strictures (especially hilar strictures) are prone to occlusion and can be a nidus for infection.50

● Combined percutaneous and endoscopic procedures.50

● Inadvertent contrast injection into an obstructed and undrained biliary segment, which can increase pressure and seed bacteria into the bloodstream.4

● Use of improperly disinfected endoscopes or accessories, which can directly introduce highly resistant organisms into the biliary tree, as seen in outbreaks of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE).2

3.4.4 Parasitic and Other Infectious Etiologies

In certain geographic regions, particularly in Asia and South America, parasitic infestations of the biliary tree are a recognized cause of cholangitis. These parasites can cause disease through several mechanisms, including mechanical obstruction of the ducts, induction of stone formation, and direct inflammatory damage to the biliary epithelium.19 Common biliary parasites include the roundworm Ascaris lumbricoides and liver flukes such as Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini.3 In immunocompromised patients, such as those with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), opportunistic infections can lead to a condition known as AIDS cholangiopathy, which can present with features of cholangitis.12

4.0 Diagnostic Techniques

The diagnosis of acute cholangitis is a clinical one, established through a combination of characteristic symptoms, supportive laboratory findings, and imaging studies that confirm biliary obstruction and/or its underlying cause.2 Prompt and accurate diagnosis is critical, as delays are associated with increased morbidity and mortality.2

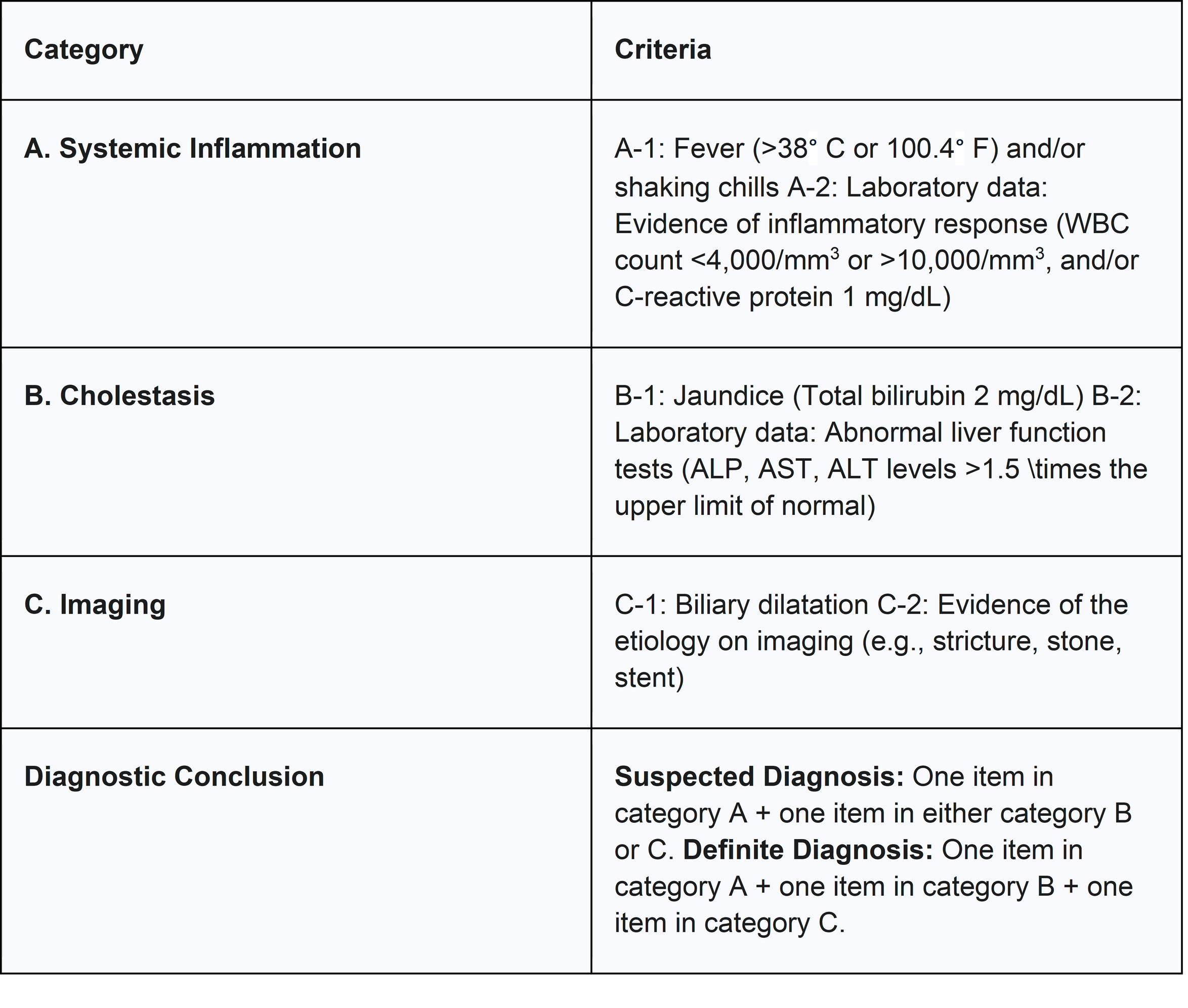

4.1 Clinical Diagnosis and the TG18 Diagnostic Criteria

The classic clinical presentations of Charcot's triad (fever, RUQ pain, jaundice) and Reynolds' pentad (the triad plus altered mental status and shock) are highly specific for acute cholangitis. The presence of the full triad has a specificity of over 95%.2 However, their clinical utility as primary diagnostic tools is severely limited by their low sensitivity. The complete Charcot's triad is present in only about 26% of patients with confirmed cholangitis, and the full pentad is even rarer, seen in only about 3% of cases.4 A significant proportion of patients, particularly the elderly or immunocompromised, may present with atypical or subtle symptoms, such as confusion or malaise without prominent fever or pain.4

Recognizing these limitations, the Tokyo Guidelines 2018 (TG18) established a more sensitive and structured set of diagnostic criteria. These criteria integrate clinical signs of systemic inflammation with laboratory evidence of cholestasis and imaging findings of biliary pathology. This multi-pronged approach has demonstrated significantly higher diagnostic sensitivity (approaching 100% in some studies) and accuracy compared to the classic triads and pentads, allowing for earlier and more reliable diagnosis.12 The formal diagnosis is made by fulfilling criteria from three distinct categories.

Table 2: Tokyo Guidelines 2018 (TG18) Diagnostic Criteria for Acute Cholangitis 6

4.2 Laboratory Investigations

Laboratory tests are essential to support the clinical diagnosis, assess severity, and guide therapy. Key investigations include 7:

● Complete Blood Count (CBC): Typically reveals leukocytosis with a neutrophilic predominance. However, leukopenia can occur in severe sepsis or in immunocompromised individuals and is an ominous sign.12

● Inflammatory Markers: C-reactive protein (CRP) is almost universally elevated and is a key component of the TG18 diagnostic criteria.6

● Liver Function Tests (LFTs): The characteristic pattern is one of cholestasis, with marked elevations in alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), accompanied by hyperbilirubinemia (elevated total and direct bilirubin).12 Transaminases (AST and ALT) are often mildly to moderately elevated.

● Coagulation Profile: An elevated PT-INR may indicate hepatic dysfunction (a criterion for severe disease) or vitamin K deficiency due to prolonged cholestasis.12

● Renal Function and Electrolytes: Serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) are monitored to assess for renal dysfunction, a common complication of sepsis.7

● Blood Cultures: These are of paramount importance and should be obtained from all patients with suspected moderate to severe cholangitis before the administration of antibiotics. They are positive in 21-71% of cases and are crucial for identifying the causative organism and guiding definitive antibiotic therapy.6

● Bile Cultures: Whenever biliary drainage is performed, a sample of bile should be sent for culture and sensitivity testing. Bile cultures have a higher yield than blood cultures and provide the most accurate information about the biliary pathogens, which is invaluable for tailoring antibiotic therapy and managing antimicrobial resistance.1

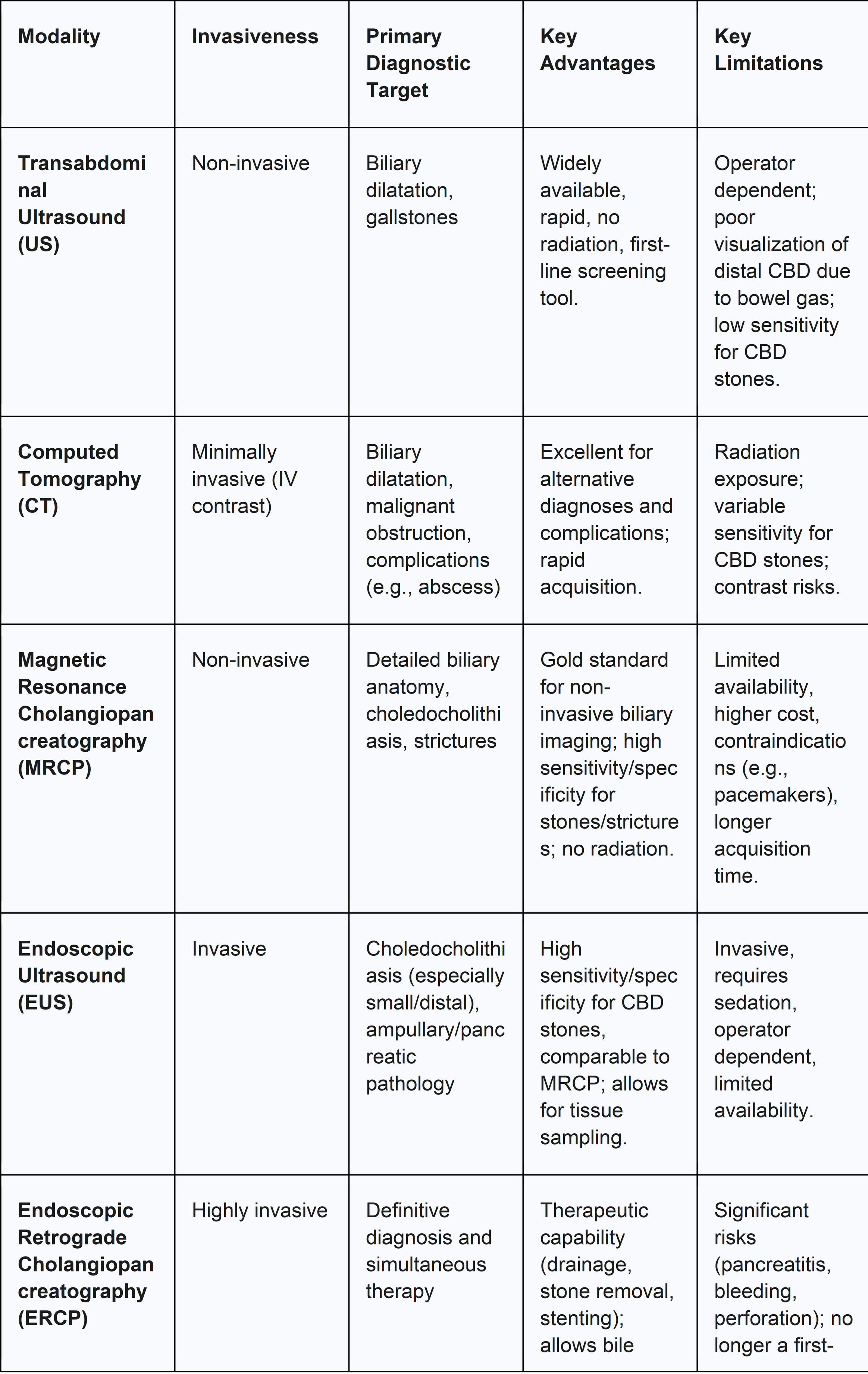

4.3 Imaging Modalities

Diagnostic imaging plays a central role in the management of acute cholangitis. Its primary objectives are to confirm the presence of biliary obstruction, identify the specific cause and location of the obstruction, and guide the selection of the appropriate therapeutic intervention. The diagnostic imaging pathway is best understood as a logical, sequential process that progresses from non-invasive, widely available screening tools to more specific, advanced, and sometimes invasive modalities. Each test answers a different clinical question, allowing for a structured approach that maximizes diagnostic yield while minimizing patient risk.

4.3.1 Transabdominal Ultrasound (US)

Ultrasound is universally recommended as the initial imaging modality for any patient with suspected biliary pathology.29 Its advantages include wide availability, non-invasiveness, lack of ionizing radiation, and low cost. The primary role of ultrasound is to assess for biliary dilatation, which is a key indicator of obstruction.58 However, its utility is limited by a relatively low sensitivity for detecting stones in the common bile duct (choledocholithiasis), especially in the distal portion, which is often obscured by overlying bowel gas.57 While a positive finding of a dilated duct or a visible stone is highly suggestive, a normal ultrasound does not rule out cholangitis, particularly in cases of early or incomplete obstruction.12

4.3.2 Computed Tomography (CT)

A CT scan of the abdomen is often performed as an adjunct to ultrasound, particularly when the diagnosis is uncertain, to exclude other causes of abdominal pain and sepsis, or to evaluate for complications.20 CT is superior to ultrasound for identifying complications such as a hepatic abscess and for detecting malignant causes of obstruction like pancreatic tumors or metastatic disease.12 While it can show biliary dilatation, its sensitivity for detecting bile duct stones is variable and often inferior to that of MRCP, as many stones are isodense to bile.29

4.3.3 Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

MRCP has become the non-invasive imaging modality of choice for definitive anatomical evaluation of the biliary tree.12 It uses heavily T2-weighted sequences to create detailed, high-resolution images of the biliary and pancreatic ducts, providing an anatomical "roadmap" without the need for contrast agents or ionizing radiation. MRCP has excellent sensitivity (>90%) and specificity (approaching 100%) for detecting choledocholithiasis, biliary strictures, and other causes of obstruction.12 Its ability to visualize the ducts both proximal and distal to an obstruction makes it an invaluable tool for planning subsequent therapeutic procedures like ERCP.29

4.3.4 Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS)

EUS is another highly accurate modality for diagnosing choledocholithiasis and evaluating the distal bile duct and head of the pancreas. It involves passing a high-frequency ultrasound probe on the tip of an endoscope into the duodenum, providing detailed images of adjacent structures without interference from bowel gas.7 Its sensitivity and specificity for detecting CBD stones are comparable to MRCP, and it may be preferred in certain clinical scenarios, such as in patients with contraindications to MRI or when there is a high suspicion of a small stone missed by other modalities.60

4.3.5 Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

ERCP is unique in that it serves as both the definitive diagnostic test and the primary therapeutic intervention.12 Diagnostically, it involves direct cannulation of the bile duct and injection of contrast material to perform a cholangiogram, which provides unparalleled detail of the biliary anatomy.61 It allows for the direct visualization of pus extruding from the papilla of Vater, which is pathognomonic for suppurative cholangitis, and enables the collection of bile for culture.2 However, due to its invasive nature and associated risks (pancreatitis, bleeding, perforation, and iatrogenic cholangitis), its role as a purely diagnostic tool has been largely supplanted by MRCP and EUS.59 Today, ERCP is reserved for patients in whom a therapeutic intervention is planned.28

5.0 Management Strategies

The management of acute cholangitis is a time-critical emergency that follows a clear and universally endorsed paradigm of concurrent but logically ordered interventions: Resuscitate, Medicate, and Decompress. This structured approach is fundamental to stabilizing the patient, controlling the systemic infection, and definitively treating the underlying cause. The first step, Resuscitate, involves immediate hemodynamic support with intravenous fluids and, if necessary, vasopressors to counteract sepsis-induced hypotension and ensure adequate organ perfusion.5 The second step, Medicate, requires the prompt administration of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics to combat bacteremia and control the systemic inflammatory response.8 The final and definitive step, Decompress, involves achieving source control through biliary drainage to relieve the obstruction, reduce intraductal pressure, and halt the ongoing seeding of bacteria into the bloodstream.6 The success of treatment hinges on the timely and effective execution of all three components, as failure or delay in any one step is directly associated with poor clinical outcomes and increased mortality.2

5.1 Medical Management

5.1.1 Initial Resuscitation and Supportive Care

All patients with a suspected or confirmed diagnosis of acute cholangitis require immediate hospitalization.12 The initial focus is on assessing the airway, breathing, and circulation (the ABCs) and initiating aggressive supportive care. This includes 6:

● Intravenous Fluid Resuscitation: Aggressive hydration with crystalloid solutions is crucial to restore intravascular volume, improve tissue perfusion, and support blood pressure.

● Electrolyte Correction: Monitoring and correcting any electrolyte abnormalities is essential.

● Analgesia: Appropriate pain management should be provided.

● NPO Status: Patients are typically kept with nothing by mouth (nil per os) in anticipation of a possible endoscopic or surgical procedure.30

● Intensive Care: Patients with Grade III (Severe) cholangitis, who exhibit signs of sepsis with organ dysfunction, require admission to an ICU for continuous monitoring and advanced organ support. This may include the use of vasopressors to maintain mean arterial pressure, mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure, and renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury.5

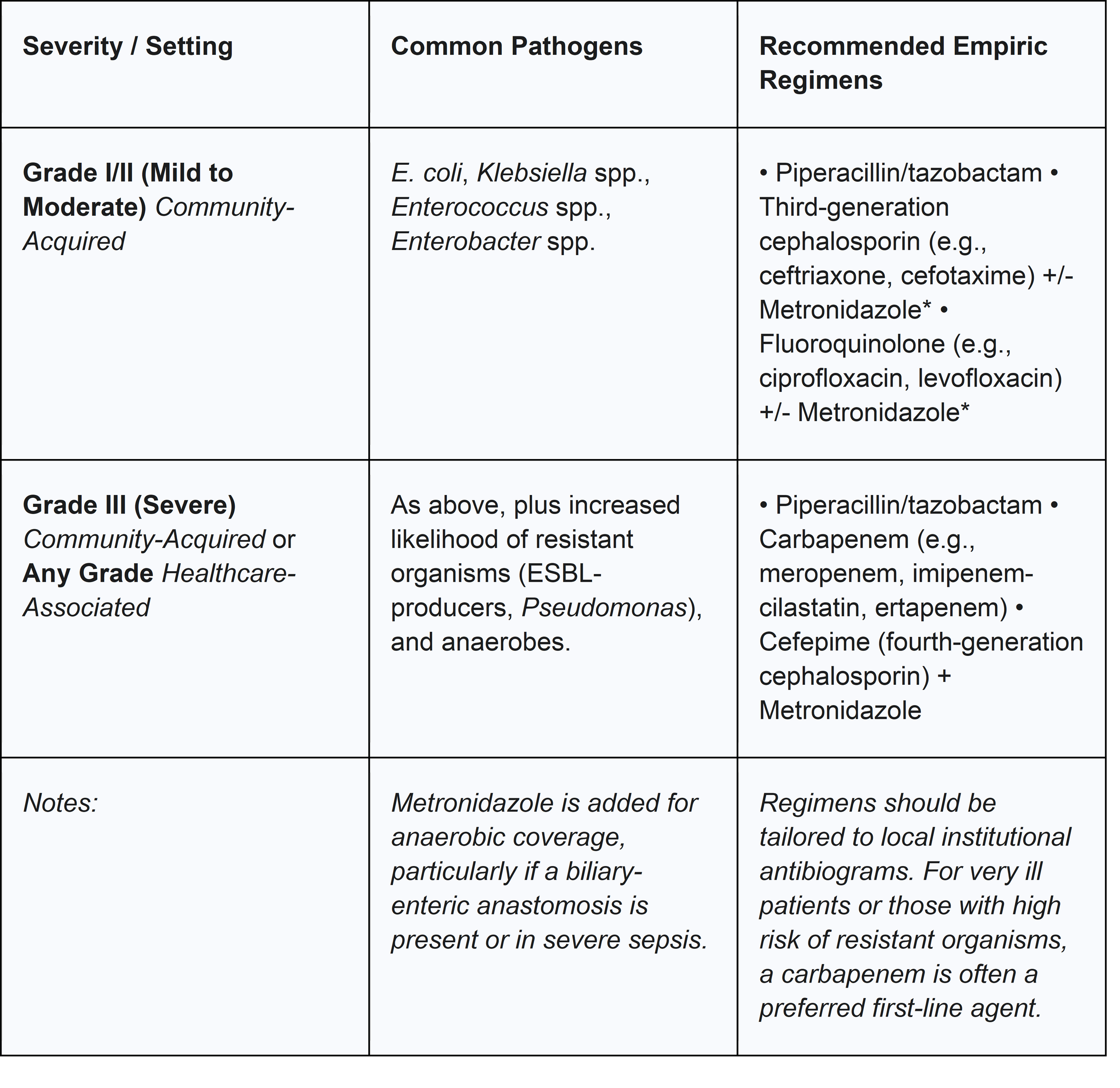

5.1.2 Antimicrobial Therapy: Empiric Regimens and Guided Treatment

Antimicrobial therapy is a cornerstone of management and should be initiated empirically as soon as the diagnosis of acute cholangitis is suspected, ideally after blood cultures have been drawn.8 The choice of empiric regimen should be broad-spectrum, providing coverage against the most common biliary pathogens, including Gram-negative enteric organisms, Enterococcus, and, in select cases, anaerobes.20 The selection should be guided by the severity of the illness, whether the infection is community- or healthcare-acquired, and local antimicrobial resistance patterns.8

Once culture and sensitivity results from blood or bile become available, the antibiotic regimen should be tailored or de-escalated to a narrower-spectrum agent that is effective against the identified pathogen(s). This practice, a key tenet of antibiotic stewardship, helps to minimize the risk of side effects and the development of further antibiotic resistance.1

Table 4: Common Pathogens and Empiric Antibiotic Regimens in Acute Cholangitis 2

5.1.3 The Evolving Landscape of Antibiotic Duration and Resistance

The optimal duration of antibiotic therapy following successful source control is a subject of ongoing debate and represents a key area of evolving practice. The TG18 guidelines recommend a course of 4-7 days of antibiotics after adequate biliary drainage.56 However, this recommendation was based partly on expert opinion, and there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that shorter courses may be equally effective. This shift reflects a broader movement toward antibiotic stewardship across medicine, driven by the understanding that once the anatomical source of infection is controlled via drainage, the bacterial burden is massively reduced, and a prolonged antibiotic course may not be necessary to clear residual bacteremia. The landmark STOP-IT trial, which studied complicated intra-abdominal infections, suggested that a fixed 4-day course of antibiotics after source control was non-inferior to longer, conventional courses.56 Although biliary infections constituted only a small subset of patients in that trial, subsequent studies focused specifically on cholangitis have supported this trend. Recent randomized controlled trials have shown that shorter durations of 3-4 days are not associated with higher rates of recurrent infection, mortality, or other adverse outcomes compared to conventional 7-8 day courses.56 This paradigm shift from "longer is safer" to using the shortest effective duration is critical in the face of the escalating global crisis of antimicrobial resistance.

This crisis poses the single greatest emerging threat to the effective management of acute cholangitis. The success of the entire "Resuscitate, Medicate, Decompress" protocol is critically dependent on the efficacy of the "Medicate" step. The increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms, including extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), directly threatens this pillar of treatment.1 Failure of empiric antibiotic therapy due to resistance can lead to uncontrolled sepsis and death, even if biliary drainage is successfully performed, potentially reversing decades of progress in reducing mortality from this disease.64 This underscores the critical importance of obtaining cultures, monitoring local resistance patterns, and judicious antibiotic use.

5.2 Interventional Management: Biliary Drainage

Biliary drainage to achieve source control is the definitive treatment for acute cholangitis and is necessary in the majority of patients.7 The timing of this intervention is dictated by the patient's clinical severity as defined by the TG18 guidelines.

5.2.1 Timing of Intervention Based on Severity

● Grade I (Mild): Patients are initially managed with antibiotics. Biliary drainage is considered only if they fail to respond to medical therapy within 24-48 hours.5

● Grade II (Moderate): Early biliary drainage is indicated, ideally performed within 48 hours of admission, to prevent clinical deterioration.5

● Grade III (Severe): Urgent biliary drainage is required as soon as the patient's general condition is stabilized with initial resuscitation, typically within 24 hours.5

5.2.2 Endoscopic Drainage

ERCP is the first-line, preferred modality for achieving biliary drainage due to its high success rate and lower morbidity and mortality compared to surgical or percutaneous approaches.8 Several techniques can be employed during ERCP to decompress the biliary system 5:

● Endoscopic Sphincterotomy (EST): This involves making a small incision in the sphincter of Oddi using an electrocautery device passed through the endoscope. This opens the bile duct orifice, facilitating drainage and allowing for subsequent stone removal.61

● Stone Extraction: If choledocholithiasis is the cause, stones can be removed immediately following sphincterotomy using a wire basket or an extraction balloon.2

● Biliary Stent Placement: In cases where definitive stone removal is difficult, unsafe (e.g., in a patient with coagulopathy), or not immediately necessary, a plastic or metal stent can be placed across the obstruction. This provides effective internal drainage by allowing bile to flow around the obstruction and into the duodenum. It is a rapid and effective method for decompression in critically ill patients.8

● Endoscopic Nasobiliary Drainage (ENBD): This involves placing a thin catheter through the endoscope, into the bile duct, and out through the patient's nose. This provides external drainage of bile. Its advantages include the ability to monitor the quantity and quality of bile output, perform cholangiograms without a repeat procedure, and flush the catheter if it becomes clogged. However, it can cause patient discomfort and is prone to accidental dislodgement.31

5.2.3 Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage (PTBD)

PTBD serves as the primary alternative drainage method when ERCP is unsuccessful or technically not feasible, for example, in patients with surgically altered anatomy (e.g., Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) that prevents endoscopic access to the papilla.8 The procedure involves passing a needle through the skin and liver parenchyma into a dilated intrahepatic bile duct under imaging guidance (ultrasound or fluoroscopy), followed by the placement of a drainage catheter. While effective, PTBD is generally considered a second-line option due to a higher rate of procedure-related complications, which can include hemorrhage, bile leak (biliary peritonitis), pneumothorax, and sepsis, as well as the significant patient discomfort associated with an external drainage catheter.8

5.2.4 EUS-Guided Biliary Drainage

In recent years, EUS-guided biliary drainage has emerged as a valuable alternative in expert centers for cases where ERCP has failed. This advanced technique involves using endoscopic ultrasound to guide the creation of a new drainage pathway from the bile duct directly into the stomach (choledochogastrostomy) or duodenum (choledochoduodenostomy), through which a stent is placed. It offers a less invasive alternative to PTBD in select patients.8

5.3 Surgical Management

Historically, open surgical drainage via choledochotomy (an incision into the common bile duct) with the placement of a T-tube was the only treatment available for acute cholangitis, and it was associated with very high mortality rates, ranging from 20% to 60%.8 With the advent and refinement of endoscopic and percutaneous techniques, the role of surgery in the acute management of cholangitis has become extremely limited. Today, emergency surgery is reserved for rare situations where less invasive methods have failed or are contraindicated, or when there is a concomitant indication for surgery, such as a perforated gallbladder or generalized peritonitis.31 Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration may be considered in stable patients as a single-stage procedure combined with cholecystectomy after the acute episode has resolved.60

5.4 Lifelong Follow-Up and Prevention of Recurrence

The management of acute cholangitis does not conclude with the resolution of the acute episode. A critical component of long-term care is addressing the underlying etiology to prevent recurrence, which is a significant risk and is associated with a poor prognosis.69

●Choledocholithiasis: For the majority of patients whose cholangitis was caused by gallstones, a cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal) is generally recommended after recovery from the acute illness to prevent future episodes of biliary colic, cholecystitis, or recurrent cholangitis.6

● Biliary Strictures: Patients with benign or malignant strictures require ongoing management, which may involve a programmed schedule of stent exchanges, balloon dilation of the stricture, or definitive surgical reconstruction (e.g., hepaticojejunostomy) in appropriate candidates.

●Long-Term Outcomes: Recurrent episodes of cholangitis can lead to progressive liver damage, secondary biliary cirrhosis, and an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma.69 Furthermore, a single severe episode, particularly one requiring complex interventions like ERCP, can have long-term consequences. A retrospective study found that patients who developed post-ERCP cholangitis had significantly worse long-term overall survival compared to those who did not, highlighting the profound impact of this complication.70 Therefore, diligent follow-up and proactive management of the underlying biliary disease are essential.

6.0 Methodology (of the Evidence Base)

The current understanding and management of acute cholangitis are built upon a hierarchy of evidence derived from various study methodologies. This evidence base ranges from foundational observational studies to high-level randomized trials and consensus-based clinical practice guidelines.

6.1 Review of Study Designs

The evidence guiding clinical practice in acute cholangitis can be conceptualized as a pyramid. At its broad base are numerous retrospective cohort studies and case series. These observational studies have been instrumental in identifying key risk factors, describing the natural history of the disease, and reporting outcomes associated with various interventions.16 While susceptible to bias, this body of work has laid the groundwork for our current understanding and has generated the hypotheses tested in more rigorous studies.

Moving up the pyramid, the middle layer consists of systematic literature reviews and a growing number of prospective studies, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses.4 These studies provide a higher level of evidence for specific clinical questions. For instance, RCTs have been crucial in comparing the efficacy of different biliary drainage techniques and, more recently, in establishing the non-inferiority of shorter-course antibiotic therapy compared to traditional longer durations.9

At the apex of this evidence pyramid are the comprehensive, consensus-driven clinical practice guidelines, most notably the Tokyo Guidelines.4 These guidelines are developed by international expert panels that systematically review the available literature. They synthesize the best available evidence from all levels of the pyramid and, where high-quality evidence is lacking, incorporate expert consensus to provide unified, actionable recommendations for diagnosis, severity assessment, and management.4 This hierarchical structure reflects a field that is maturing from a practice based largely on expert opinion and observation toward one that increasingly refines its standards through high-level, evidence-based research.

6.2 Ethical Considerations in Clinical Research for Acute Cholangitis

Conducting clinical trials in the setting of an acute, life-threatening condition like severe cholangitis presents unique and significant ethical challenges. The principles of bioethics—respect for persons, beneficence, and justice—must be rigorously applied to protect vulnerable patients.

● Informed Consent: Obtaining fully informed consent is arguably the most critical and challenging ethical requirement.75 Patients with acute cholangitis are often in severe pain, acutely ill, and may be suffering from sepsis-induced altered mental status, which can impair their capacity to comprehend complex trial information and make a voluntary decision.75 Researchers have an ethical obligation to use simple language, ensure information is adequately disclosed, and, when necessary, involve legally authorized representatives. The "therapeutic misconception"—the patient's belief that participation in a trial guarantees personal benefit—must be actively avoided.75

● Risk-Benefit Ratio: Any proposed research must have a favorable risk-benefit ratio. The potential benefits to the participant and to society must outweigh the inherent risks.75 This is particularly salient in cholangitis, where standard-of-care treatments like biliary drainage are life-saving. The use of a placebo control in place of a proven, effective therapy would be unethical. Therefore, clinical trials typically compare a new intervention against the current standard of care, or compare two accepted standards (e.g., short-course vs. long-course antibiotics).74 An independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board must be in place to monitor for excessive harm or clear benefit in one arm of the trial, with pre-specified rules for stopping the study early.75

● Fair Subject Selection: The principles of justice demand that the selection of trial participants is fair and equitable. Inclusion and exclusion criteria should be based on scientific rationale and designed to answer the research question, not to exclude vulnerable or disadvantaged populations.75

● Independent Review: All clinical research must undergo review and approval by an independent ethics committee or Institutional Review Board (IRB) before initiation. The IRB's role is to ensure that the study design is scientifically valid and ethically sound, and that the rights and welfare of the human subjects are protected throughout the trial.75

7.0 Modeling and Analysis

In recent years, there has been a significant effort to move beyond simple clinical criteria and develop more sophisticated models for predicting outcomes in patients with acute cholangitis. These models aim to provide a more granular and personalized risk assessment, helping clinicians to identify high-risk patients who may benefit from more aggressive monitoring and earlier intervention.

7.1 Statistical Models for Predicting Outcomes and Mortality

Early efforts in prognostic modeling relied on traditional statistical methods, primarily univariate and multivariate logistic regression, to identify independent predictors of adverse outcomes. Several studies have successfully used this approach to pinpoint key prognostic indicators available at the time of hospital admission. For example, a retrospective analysis identified an admission WBC count 20,000/mm3 and a total bilirubin level 10 mg/dL as statistically significant predictors of organ failure or death.53 Another study using multivariate analysis found that a higher American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical classification score and a delay in ERCP of greater than 72 hours were independently associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including persistent organ failure and 30-day mortality.65

More advanced statistical techniques have also been applied. One notable study investigated eleven different statistical models to predict in-hospital mortality using 22 predictor variables. Among these, a Random Forest model demonstrated the best performance, achieving a mean area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 91.5%. This model showed excellent ability to stratify patients into high- and low-risk groups, with a very high negative predictive value of 99.3%, suggesting it could be a powerful tool for ruling out high-risk disease.72

7.2 Application of Machine Learning in Risk Stratification

The evolution of prognostic modeling has now entered the era of machine learning (ML), which allows for the analysis of complex, non-linear relationships among a vast number of variables. A recent study developed and validated prediction models for cholelithiasis-induced acute cholangitis using nine different ML algorithms, including Logistic Regression, eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Support Vector Machines.80 The models were trained on 186 variables to predict three key outcomes: in-hospital mortality, re-admission within 30 days, and mortality within 180 days.

The XGBoost algorithm consistently demonstrated the most optimal predictive efficacy. In the training set, it achieved exceptionally high performance, with an AUROC of 0.996 for in-hospital mortality and 0.988 for 180-day mortality. The models maintained strong performance in internal validation (AUROC of 0.967 for in-hospital mortality) and showed good performance in an external validation cohort.80 A crucial aspect of this work is the translation of these complex models into user-friendly online prediction platforms, which have the potential to bring sophisticated, real-time risk assessment directly to the clinician at the bedside.79

This progression from broad, categorical risk stratification systems like the TG18 guidelines to continuous, quantitative risk prediction using advanced modeling represents a significant paradigm shift. While the TG18 system remains invaluable for its simplicity and utility in initial triage and management decisions, statistical and ML models offer the potential for a more granular, dynamic, and personalized prognosis. By integrating dozens of clinical and laboratory variables, these models can generate a specific probability of an adverse outcome for an individual patient. This allows for a more nuanced approach to care, helping to guide decisions about the intensity of monitoring, the timing of intervention, and the allocation of healthcare resources, such as ICU admission, beyond what is possible with a three-tiered classification system alone.

8.0 Results and Discussion

8.1 Synthesis of Clinical Outcomes and Prognostic Indicators

Acute cholangitis remains a condition with substantial morbidity and mortality. Despite modern management, overall mortality rates are frequently reported in the range of 2-10%, and can be significantly higher in severe cases or when treatment is delayed.16 Organ failure is a common and serious complication, occurring in up to 25% of patients in some series, and is a primary driver of mortality.53

A consistent set of prognostic indicators has been identified across numerous studies, allowing for the early identification of patients at high risk for adverse outcomes. These can be broadly categorized:

● Laboratory Markers: Several admission laboratory values are powerful predictors. A high WBC count (specifically 20,000/mm3) and marked hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin 10 mg/dL) have been shown to be selective predictors of organ failure and death.53 Other markers of severe inflammation and organ dysfunction, such as elevated CRP, hypoalbuminemia, elevated creatinine, and coagulopathy (prolonged PT-INR, thrombocytopenia), are also associated with poor prognosis and form the basis of the TG18 severity criteria.4

● Clinical Factors: Advanced age (specifically 75 years) is a consistent and independent risk factor for mortality.4 The presence of underlying malignancy as the cause of obstruction is also associated with worse outcomes compared to benign etiologies like choledocholithiasis.58 Clinical signs of sepsis, such as hypotension (shock) and altered mental status, are the most ominous prognostic factors and define Grade III disease.4

● Process of Care Measures: Delays in achieving definitive biliary drainage are strongly and consistently associated with worse clinical outcomes. Studies have shown that a delay in performing ERCP beyond 48-72 hours is linked to prolonged hospital stays, increased complications, and higher mortality, particularly in patients with moderate to severe disease.9

8.2 Challenges in Management: Antimicrobial Resistance and Complex Cases

Despite a well-established and effective management protocol, several significant challenges complicate the treatment of acute cholangitis in the modern era. The most pressing of these is the global rise of antimicrobial resistance. The entire management strategy relies on the ability of empiric antibiotics to control bacteremia and prevent progression to septic shock while arrangements are made for biliary drainage. The increasing prevalence of MDR pathogens directly undermines this critical step.

Studies from around the world report alarming rates of resistance among the common biliary pathogens to first- and second-line antibiotics.10 Resistance to third-generation cephalosporins and piperacillin-tazobactam is common, and the emergence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in biliary infections represents a dire therapeutic challenge.2 This resistance is not a theoretical concern; it is directly linked to treatment failure and increased mortality rates.64 Patients with a history of prior biliary interventions (such as ERCP or stent placement) and those with healthcare-associated infections are at particularly high risk for harboring resistant organisms.11 This evolving microbial landscape makes the selection of appropriate empiric therapy increasingly difficult and places a greater emphasis on adhering to principles of antibiotic stewardship: obtaining blood and bile cultures whenever possible, being aware of local antibiogram data, and de-escalating therapy once sensitivities are known.1

8.3 Emerging Therapies and Future Directions in Cholangitis Treatment

The landscape of therapeutic innovation in the field of cholangitis reveals a notable dichotomy. For chronic, autoimmune cholangiopathies like PBC and PSC, there is a vibrant and rapidly advancing pipeline of novel pharmacological agents. These therapies are designed to modulate the underlying immune-mediated inflammation and fibrotic processes that drive these diseases. Emerging treatments for PBC and PSC include peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) agonists (e.g., elafibranor, seladelpar), ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT) inhibitors, and various biologic agents targeting specific inflammatory pathways.81 These drugs aim to alter the natural history of the chronic disease, a goal distinct from managing an acute infectious episode.

In stark contrast, innovation for acute bacterial cholangitis is not focused on the development of new drugs. Instead, research and progress are centered on process optimization and the refinement of existing strategies. The core pathophysiological principles of acute bacterial cholangitis—obstruction leading to infection and sepsis—are considered well-understood, and the current treatment paradigm of antibiotics and drainage is highly effective when implemented correctly. Therefore, future improvements in patient outcomes are expected to come from:

● Refining the Timing and Techniques of Drainage: Ongoing research seeks to determine the precise optimal timing for intervention and to improve the safety and efficacy of endoscopic and percutaneous drainage techniques.

● Promoting Antibiotic Stewardship: As discussed, a major focus is on determining the shortest effective duration of antibiotic therapy to combat resistance without compromising patient outcomes.56

● Developing Better Predictive Models: The use of machine learning and advanced statistical modeling to create more accurate, personalized risk stratification tools will allow for better triage of patients and more efficient allocation of healthcare resources.72

This divergence suggests that the path to better outcomes in acute bacterial cholangitis lies not in a "magic bullet" drug, but in the systematic improvement of how, when, and for whom we deliver the effective therapies that are already available.

9.0 Conclusion

9.1 Summary of Key Findings

Acute bacterial cholangitis is a serious and potentially fatal infectious disease of the biliary system, defined by the critical interplay of biliary obstruction and bacterial infection. Its clinical course can be precipitous, progressing rapidly from a localized infection to systemic sepsis and multi-organ failure. The Tokyo Guidelines 2018 have provided an indispensable and globally accepted framework for the standardized diagnosis and, most importantly, the severity-stratified management of this condition. This evidence-based approach allows for rapid clinical triage and directs the timing of intervention. The fundamental treatment paradigm is clear and time-sensitive, resting on three pillars: aggressive resuscitation and supportive care, prompt initiation of broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy, and definitive source control via timely biliary drainage. While this management strategy has significantly reduced mortality over the past several decades, major challenges remain. The foremost among these is the growing global crisis of antimicrobial resistance, which threatens the efficacy of empiric antibiotic therapy and complicates patient management. Future advancements in care are likely to stem from the optimization of current treatment protocols, including antibiotic stewardship and refined drainage techniques, as well as the development of sophisticated predictive models for more personalized risk stratification.

9.2 Final Recommendations for Clinical Practice

Based on the synthesis of current evidence, the following recommendations are crucial for the optimal management of patients with acute bacterial cholangitis:

1. Adherence to TG18 Guidelines: Clinicians should strictly adhere to the Tokyo Guidelines 2018 for both the diagnosis and severity grading of acute cholangitis. This framework should be used to guide initial triage and determine the urgency of intervention.

2. Prompt Initiation of Comprehensive Care: Upon suspicion of acute cholangitis, patients should be hospitalized, and comprehensive medical management—including aggressive fluid resuscitation, electrolyte correction, and appropriate supportive care—should be initiated immediately.

3. Timely Antimicrobial Therapy and Culture Collection: Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics should be administered as early as possible, but only after blood cultures have been obtained in all patients with suspected moderate to severe disease. The empiric regimen should be chosen based on disease severity, local resistance patterns, and patient-specific risk factors.

4. Culture-Guided De-escalation: Bile cultures should be obtained during any drainage procedure. Antibiotic therapy should be de-escalated to the narrowest effective agent based on culture and sensitivity results to promote antibiotic stewardship.

5. Severity-Directed Biliary Drainage: The decision for and timing of biliary drainage must be guided by the TG18 severity grade. Endoscopic drainage via ERCP is the first-line modality. Urgent consultation with gastroenterology or interventional radiology is mandatory for patients with moderate or severe disease.

6. Treatment of Underlying Etiology: Following resolution of the acute episode, a definitive plan must be made to address the underlying cause of biliary obstruction (e.g., cholecystectomy for gallstones, management of strictures) to prevent recurrence.

10.0 Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the numerous researchers, clinicians, and members of the international working groups whose dedicated efforts have contributed to the body of knowledge synthesized in this review. Their work has been instrumental in advancing the understanding and management of acute cholangitis.

11.0 References

Works cited

1. Acute cholangitis: a state-of-the-art review - PMC, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11305776/

2. Acute cholangitis - an update - PMC - NIH, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5823698/

3. Definitions, pathophysiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis ..., accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2784509/

4. Acute Bacterial Cholangitis - PMC - NIH, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4569195/

5. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: initial management of acute biliary infection and flowchart for acute cholangitis - PubMed, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28941329/

6. Tokyo Guidelines for Acute Cholangitis 2018 - MDCalc, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/10142/tokyo-guidelines-acute-cholangitis-2018

7. Acute cholangitis - Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment | BMJ Best Practice US, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/345

8. Management of Acute Cholangitis - PMC, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3061017/

9. ASGE guideline on the management of cholangitis, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.asge.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/piis0016510720351117.pdf?sfvrsn=bad7c25d_1

10. Comparative Analysis of Microbial Species and Multidrug ..., accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10813899/

11. Microbial Profile and Antibiotic Resistance Patterns in Bile Aspirates from Patients with Acute Cholangitis: A Multicenter International Study - MDPI, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6382/14/7/679

12. Cholangitis - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf - NIH, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558946/

13. Classification and Management of Acute Cholangitis, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.pajtcces.com/abstractArticleContentBrowse/PAJT/31336/JPJ/fullText

14. (PDF) Tokyo Guidelines 2018: initial management of acute biliary infection and flowchart for acute cholangitis - ResearchGate, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320005035_Tokyo_Guidelines_2018_initial_management_of_acute_biliary_infection_and_flowchart_for_acute_cholangitis

15. Acute cholangitis - an update - Baishideng Publishing Group, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v9/i1/1.htm

16. Impact of Hospital Teaching Status on Outcomes of Acute Cholangitis - PubMed Central, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12151124/

17. Performance of diagnostic tools for acute cholangitis in patients with suspected biliary obstruction - PMC - NIH, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9306734/

18. Study Details | NCT04216745 | Microbial Analysis in Patients With Cholangitis | ClinicalTrials.gov, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04216745

19. Bacterial and parasitic cholangitis - PubMed, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9581592/

20. Acute Cholangitis - Bile Duct and Gallbladder Diseases - empendium.com, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://empendium.com/mcmtextbook/chapter/B31.II.6.4.

21. 2239. Antibiotic Sensitivity Spectrum Of Acute Bacterial Cholangitis: Trends From A Tertiary Referral Center In Pakistan | Open Forum Infectious Diseases | Oxford Academic, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/ofid/article/10/Supplement_2/ofad500.1861/7446893

22. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis - PubMed, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29090866/

23. Cholangitis: Types, Symptoms, Treatment - Cleveland Clinic, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/cholangitis

24. Primary Biliary Cholangitis - AASLD, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.aasld.org/practice-guidelines/primary-biliary-cholangitis

25. Primary biliary cholangitis - Symptoms and causes - Mayo Clinic, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/primary-biliary-cholangitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20376874

26. Reasons why women are more likely to develop primary biliary cholangitis - Semantic Scholar, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4206/4a3040f3a5d6d2bd416b667b16aff99ffe30.pdf?skipShowableCheck=true

27. Maternal liver-related symptoms during pregnancy in primary sclerosing cholangitis - PMC, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10711472/

28. Choledocholithiasis and Cholangitis - Hepatic and Biliary Disorders - Merck Manuals, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/hepatic-and-biliary-disorders/gallbladder-and-bile-duct-disorders/choledocholithiasis-and-cholangitis

29. Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis: From Imaging to Intervention | AJR, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://ajronline.org/doi/10.2214/AJR.08.1104

30. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: initial management of acute biliary infection and flowchart for acute cholangitis, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://dashboard.protocolosclinicos.com.br/download/anexo/2282/documento-oficial-tokyo.pdf

31. Managing Acute Cholangitis - News-Medical, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.news-medical.net/health/Managing-Acute-Cholangitis.aspx

32. Acute Cholangitis in Adults Clinical Guideline - rcht.nhs.uk, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://doclibrary-rcht.cornwall.nhs.uk/DocumentsLibrary/RoyalCornwallHospitalsTrust/Clinical/GeneralSurgery/AcuteCholangitisInAdultsClinicalGuideline.pdf

33. Tokyo Classification Cholangitis (Guidelines) - Endoscopy Campus, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.endoscopy-campus.com/en/classifications/tokyo-classification-cholangitis-guidelines/

34. Linking To "Tokyo Guidelines 2018: initial management of acute biliary infection and flowchart for acute cholangitis" - Tom Wade MD, accessed on October 29, 2025, http://www.tomwademd.net/linking-to-tokyo-guidelines-2018-initial-management-of-acute-biliary-infection-and-flowchart-for-acute-cholangitis/

35. Acute cholangitis - Symptoms, Causes, Images, and Treatment Options - Epocrates, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.epocrates.com/online/diseases/345/acute-cholangitis

36. The Genetics and Epigenetics of Primary Biliary Cholangitis - PubMed, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30259846/

37. Cholangiocytes and the environment in primary sclerosing cholangitis: where is the link? | Gut, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://gut.bmj.com/content/66/11/1873

38. Environmental risk factors and comorbidities of primary biliary cholangitis in Korea: a case-control study - ResearchGate, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340205580_Environmental_risk_factors_and_comorbidities_of_primary_biliary_cholangitis_in_Korea_a_case-control_study

39. Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy - American Liver Foundation, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://liverfoundation.org/liver-diseases/complications-of-liver-disease/intrahepatic-cholestasis-of-pregnancy-icp/

40. Considerations After an Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy - ICP Care, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://icpcare.org/healthcare-provider/considerations-after-intrahepatic-cholestasis-pregnancy/

41. Women with PBC may be at high risk of disease flares after childbirth, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://liverdiseasenews.com/news/women-pbc-high-risk-disease-flares-following-childbirth-study/

42. Environmental factors, medical and family history, and comorbidities ..., accessed on October 29, 2025, https://teikyo-u.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/2000392/files/td90100248_zenbun.pdf

43. Environmental Factors in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis - PMC - NIH, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4232304/

44. Environmental exposure as a risk-modifying factor in liver diseases: Knowns and unknowns, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8727918/

45. Acute Cholangitis - DynaMed, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.dynamed.com/condition/acute-cholangitis

46. ASGE guideline on the role of endoscopy in the evaluation and management of choledocholithiasis, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.asge.org/docs/default-source/guidelines/asge-guideline-on-the-role-of-endoscopy-in-the-evaluation-and-management-of-choledocholithiasis-2019-june-gie.pdf?sfvrsn=6757df52_4

47. Recurrent choledocholithiasis with cholangitis 30 years post-cholecystectomy with negative ERCP: a case report - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11981434/

48. Management of Malignant Biliary Obstruction - PMC - NIH, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5088103/

49.pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5088103/#:~:text=Malignant%20biliary%20obstruction%20usually%20presents,appetite%2C%20nausea%2C%20and%20vomiting.

50. Complications of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography: How to Avoid and Manage Them - PMC - NIH, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3980992/

51. Predictive Factors Associated with Cholangitis Following Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography - SAGES Abstract Archives, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.sages.org/meetings/annual-meeting/abstracts-archive/predictive-factors-associated-with-cholangitis-following-endoscopic-retrograde-cholangiopancreatography/

52. Cholangitis | MUSC Health | Charleston SC, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://muschealth.org/medical-services/ddc/patients/digestive-diseases/pancreas/cholangitis

53. Cholangitis: Analysis of Admission Prognostic Indicators and ..., accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5863741_Cholangitis_Analysis_of_Admission_Prognostic_Indicators_and_Outcomes

54. Tokyo Guidelines (TG18) for Acute Cholangitis Provide Improved Specificity and Accuracy Compared to Fellow Assessment - NIH, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9427126/

55. What is the recommended initial treatment for acute cholangitis according to the Tokyo Guidelines?, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.droracle.ai/articles/419586/according-to-tokyo-guideline

56. What is the proper antibiotic duration for cholangitis? - IDSA, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.idsociety.org/science-speaks-blog/2024/what-is-the-proper-antibiotic-duration-for-cholangitis/

57. Modern imaging of cholangitis - PMC, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9327751/

58. Acute cholangitis | Radiology Reference Article - Radiopaedia.org, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://radiopaedia.org/articles/acute-cholangitis

59. Imaging of Biliary Tract Disease | AJR - American Journal of Roentgenology, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://ajronline.org/doi/10.2214/AJR.10.4341

60. Clinical Spotlight Review: Management of Choledocholithiasis - A SAGES Publication, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.sages.org/publications/guidelines/clinical-spotlight-review-management-of-choledocholithiasis/

61. Techniques of biliary drainage for acute cholangitis: Tokyo ... - NIH, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2784512/

62. Antibiotic Therapy of 3 Days May Be Sufficient After Biliary Drainage for Acute Cholangitis: A Systematic Review | springermedizin.de, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.springermedizin.de/antibiotic-therapy-of-3-days-may-be-sufficient-after-biliary-dra/18779738

63. Antimicrobial therapy of 3 days or less is sufficient after successful ERCP for acute cholangitis - NIH, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7226689/

64. Is Antibiotic Resistance Microorganism Becoming a Significant Problem in Acute Cholangitis in Korea? - Clinical Endoscopy, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.e-ce.org/journal/view.php?number=6365

65. Factors predicting adverse short-term outcomes in patients with acute cholangitis undergoing ERCP: A single center experience - PMC - NIH, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3952163/

66. Optimal drainage method for acute cholangitis according to updated ..., accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/gekakansen/17/3/17_119/_article/-char/en

67. Is percutaneous drainage a viable option for managing acute cholangitis? - Dr.Oracle AI, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://droracle.ai/articles/440548/is-percutaneous-drainage-a-viable-option-for-managing-acute-cholangitis

68. Outcomes of Acute Cholangitis in Maharat Nakhon Ratchasima Hospital - ThaiJO, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/ThaiJSurg/article/view/239909

69. Analysis of Pathogenic Bacteria Distribution and Related Factors in Recurrent Acute Cholangitis - Dove Medical Press, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.dovepress.com/analysis-of-pathogenic-bacteria-distribution-and-related-factors-in-re-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-IDR

70. Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography cholangitis ..., accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12335147/

71. Clinical and biochemical factors for bacteria in bile among patients with acute cholangitis, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11608589/

72. Mortality Risk for Acute Cholangitis (MAC): a risk prediction model ..., accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4746925/

73. Acute Bacterial Cholangitis - PubMed, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26468310/

74. Blood cultures to guide antibiotic therapy in mild-to-moderate acute cholangitis - SHEA, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://shea-online.org/shea-journal-club/february-2025/blood-cultures-to-guide-antibiotic-therapy-in-mild-to-moderate-acute-cholangitis/

75. Ethical guideposts to clinical trials in oncology - PMC, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1891175/

76. Ethics In Clinical Trials: Regulations And Ethical Concerns, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.allclinicaltrials.com/blog/clinical-trial-ethics

77. Study Details | NCT05750966 | Short-course Antibiotics vs Standard ..., accessed on October 29, 2025, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05750966?cond=%22Cholangitis%22&aggFilters=status:not%20rec&rank=1