Diseases of Thyroid Gland in Children

1. Sabi Henna

2. Gulnaz Osmonova

(1. Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.

2. Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Osh, Kyrgyz Republic.)

ABSTRACT

Thyroid disease in children is a significant health concern, encompassing a range of disorders, from congenital hypothyroidism to autoimmune thyroid diseases like Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Graves' disease. These conditions can have a profound impact on growth, cognitive development, and overall quality of life if not diagnosed and treated promptly. Congenital hypothyroidism is one of the most common preventable causes of intellectual disability and developmental delay, and early screening through newborn blood tests has markedly improved outcomes. Other thyroid disorders, such as autoimmune thyroiditis, typically manifest during adolescence and can lead to either hypo- or hyperthyroidism. The clinical presentation in children may vary from subtle symptoms like fatigue, weight changes, or growth disturbances to more pronounced manifestations like goiter, tremors, or palpitations. Diagnosis is primarily based on thyroid function tests, including measurements of serum TSH, free T4, and thyroid antibodies. Treatment typically involves hormone replacement therapy in hypothyroid cases or antithyroid medications and sometimes surgery in hyperthyroid cases. Regular monitoring is essential to ensure appropriate management and to mitigate potential long-term effects. This review emphasizes the importance of early recognition and individualized treatment to minimize the adverse impacts of thyroid disorders on children’s health and development

Keyword: Hashimoto's thyroiditis ; Graves' disease

INTRODUCTION

Thyroid gland disorders represent some of the most common endocrine conditions affecting the pediatric population. The thyroid gland plays a crucial role in regulating metabolism, growth, and neurodevelopment through the production of thyroid hormones. Any dysfunction in thyroid hormone synthesis, secretion, or action during childhood can significantly interfere with physical growth, brain development, and overall health. Because childhood is a critical period for development, thyroid diseases in children require early recognition and appropriate management to prevent long-term complications.

Thyroid disorders in children include a wide spectrum of conditions, ranging from congenital abnormalities, such as congenital hypothyroidism, to acquired disorders, including autoimmune thyroid diseases like Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Graves’ disease. While congenital hypothyroidism is a leading preventable cause of intellectual disability worldwide, acquired thyroid diseases often emerge during late childhood or adolescence and may present with subtle or nonspecific symptoms. These variations in presentation can make diagnosis challenging.

Advances in newborn screening programs and improved diagnostic techniques have significantly enhanced early detection and outcomes of pediatric thyroid diseases. However, delayed diagnosis still occurs, particularly in resource-limited settings or in cases with atypical presentations. Understanding the clinical features, diagnostic approaches, and management strategies of thyroid disorders in children is essential for pediatricians and healthcare providers.

METHODOLOGICAL OVERVIEW

Relevant studies were identified through systematic searches of electronic databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus. Keywords used in the search strategy included “pediatric thyroid disease,” “congenital hypothyroidism,” “autoimmune thyroid disorders in children,” “Graves’ disease,” and “Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.” Articles published in English within the last 10–15 years were primarily considered to ensure contemporary clinical relevance, although seminal earlier studies were also included when appropriate.

Inclusion criteria encompassed original research articles, clinical trials, review articles, and established clinical guidelines focusing on thyroid disorders in children and adolescents. Studies involving adult populations exclusively or lacking pediatric-specific data were excluded. Data extraction focused on study design, patient demographics, diagnostic criteria, treatment modalities, and reported outcomes.

The selected literature was critically analysed and organised into thematic sections covering types of thyroid disorders, clinical presentation, diagnostic evaluation, and therapeutic interventions. Emphasis was placed on evidence-based practices and consensus recommendations to provide a comprehensive and clinically applicable overview. This methodological approach allows for an integrated understanding of paediatric thyroid diseases while highlighting gaps in current knowledge and areas requiring further research.

Global Epidemiological Patterns of Thyroid Gland Diseases in Children

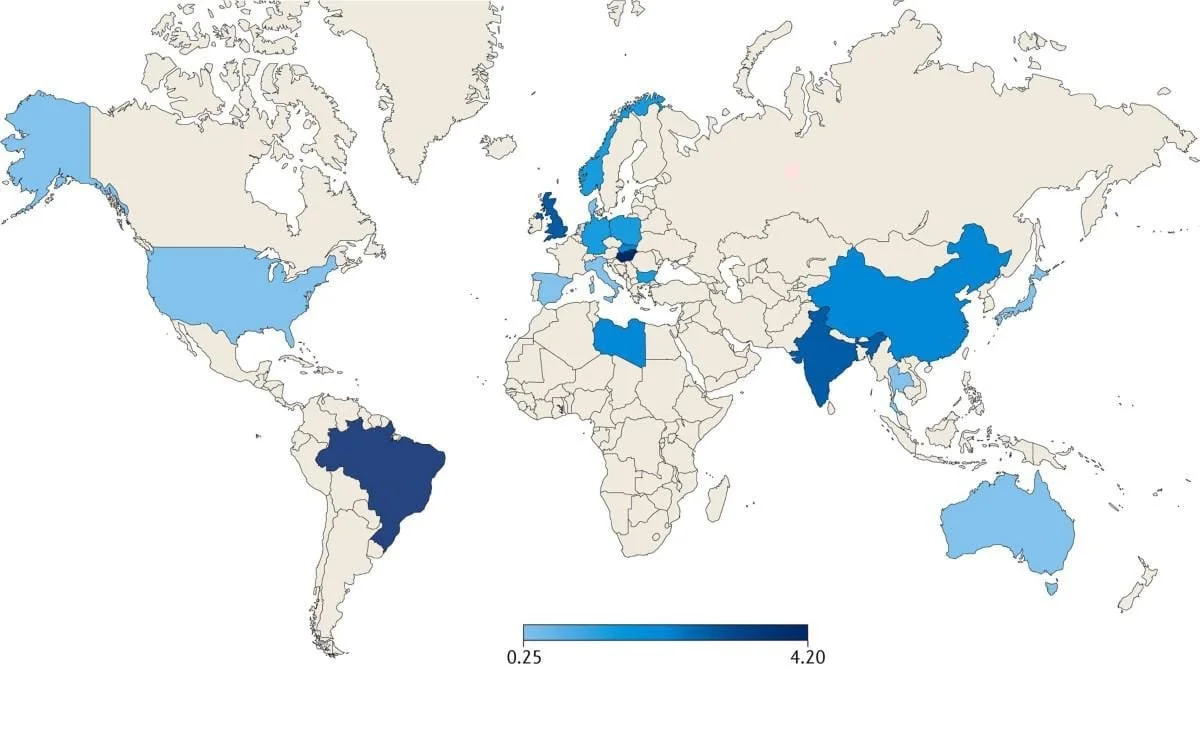

Thyroid gland disorders are among the most common endocrine diseases affecting children worldwide, though their incidence and prevalence vary significantly by geographic region, iodine status, age group, and sex. The global epidemiology of paediatric thyroid diseases reflects a combination of genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, nutritional status, and healthcare access, particularly newborn screening programs.

Global Incidence and Prevalence: -

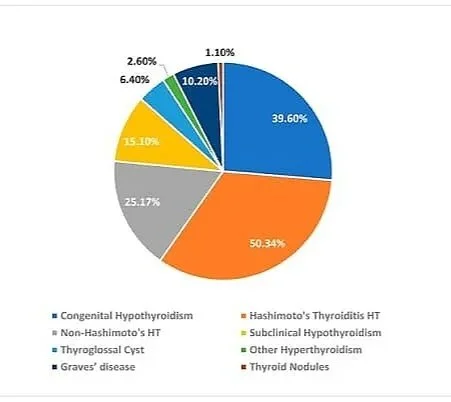

Congenital hypothyroidism is the most frequently identified thyroid disorder in neonates, with a global incidence generally estimated at approximately 1 in 2,000 to 4,000 live births. Regions with well-established newborn screening programs report higher detection rates due to improved diagnostic sensitivity. In contrast, acquired thyroid disorders, particularly autoimmune thyroid diseases, are more prevalent in older children and adolescents. Autoimmune thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) is the most common cause of hypothyroidism in children beyond infancy, while Graves’ disease remains the leading cause of paediatric hyperthyroidism worldwide.

Iodine deficiency continues to influence the global burden of thyroid disease, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. In iodine-deficient regions, goitre and hypothyroidism remain more prevalent, whereas iodine-sufficient or iodine-excess regions report higher rates of autoimmune thyroid disorders.

Age Distribution: -

The epidemiology of thyroid diseases in children shows a distinct age-related pattern. Congenital hypothyroidism presents at birth and is typically detected through neonatal screening programs. Acquired thyroid disorders are uncommon in early childhood but increase in prevalence with age, particularly during late childhood and adolescence. Autoimmune thyroid diseases most frequently manifest during puberty, likely due to hormonal changes and immune modulation associated with this developmental stage.

Gender Distribution: -

A consistent female predominance is observed across most paediatric thyroid disorders, particularly autoimmune thyroid diseases. The female-to-male ratio increases with age and is most pronounced during adolescence, often ranging from 3:1 to 5:1. This gender disparity is thought to be influenced by genetic, hormonal, and immunological factors. In contrast, congenital hypothyroidism shows a less marked gender difference, though a slight female predominance has been reported in some populations.

Regional Variations: -

Significant regional differences exist in the epidemiology of paediatric thyroid diseases. Developed countries with comprehensive screening programs report earlier diagnosis and better disease surveillance, whereas underdiagnosis remains a concern in resource-limited settings. Environmental exposure, iodine intake, and genetic background contribute to regional variability in disease patterns.

Risk Factors for Thyroid Gland Diseases in Children

Thyroid gland diseases in children arise from a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, nutritional, and immunological factors. Identification of these risk factors is essential for early diagnosis, prevention, and effective management.

Genetic and Familial Factors

Genetic predisposition plays a significant role in the development of paediatric thyroid disorders. Children with a family history of thyroid disease, particularly autoimmune thyroid disorders such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Graves’ disease, are at increased risk. Certain genetic syndromes, including Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, and other chromosomal abnormalities, are strongly associated with a higher prevalence of thyroid dysfunction.

Autoimmune Factors

Autoimmune mechanisms are a leading cause of acquired thyroid disease in children. The presence of thyroid autoantibodies increases the likelihood of developing autoimmune thyroiditis or Graves’ disease. Children with other autoimmune conditions, such as type 1 diabetes mellitus, celiac disease, or autoimmune adrenal disorders, have an elevated risk of thyroid dysfunction due to shared immunological pathways.

Iodine Imbalance

Both iodine deficiency and excess are important risk factors for thyroid disease in children. Iodine deficiency remains a major contributor to hypothyroidism and goitre in many regions of the world, particularly in low-resource settings. Conversely, excessive iodine intake may trigger autoimmune thyroid disease in genetically susceptible children.

Prenatal and Perinatal Factors

Maternal thyroid disease during pregnancy, inadequate maternal iodine intake, and exposure to antithyroid medications can adversely affect fatal thyroid development. Prematurity, low birth weight, and exposure to iodine-containing antiseptics in the neonatal period have also been linked to an increased risk of thyroid dysfunction.

Environmental and Lifestyle Factors

Exposure to environmental endocrine-disrupting chemicals, such as pesticides, industrial pollutants, and certain plastics, has been associated with altered thyroid function. Radiation exposure, particularly to the head and neck during childhood, is a well-established risk factor for thyroid nodules and malignancy.

Medications and Medical Interventions

Certain medications, including lithium, amiodarone, interferon, and antiepileptic drugs, may interfere with thyroid hormone synthesis or metabolism. Children undergoing chemotherapy or radiotherapy are also at increased risk of developing thyroid dysfunction.

Age and Gender

Age and gender influence the risk of thyroid disease in children. Autoimmune thyroid disorders are more common in older children and adolescents, with a marked female predominance, particularly after puberty. Hormonal changes during adolescence may contribute to this increased susceptibility.

Paediatric Treatment of Thyroid Gland Diseases

Management of thyroid gland diseases in children aims to restore and maintain normal thyroid hormone levels, ensure optimal growth and neurodevelopment, alleviate symptoms, and prevent long-term complications. Treatment strategies vary depending on the type of thyroid disorder, the child's age, the severity of the disease, and the underlying aetiology. Management typically includes pharmacological therapy, radioactive iodine (in selected cases), and surgical intervention, along with long-term monitoring.

1. Treatment of Hypothyroidism in Children

A. Congenital Hypothyroidism

First-line treatment:

Levothyroxine (L-thyroxine) is the treatment of choice and should be initiated as early as possible, ideally within the first 2 weeks of life.

Medication: Levothyroxine sodium (oral)

Dosage (weight-based):

Newborns (0–6 months): 10–15 µg/kg/day

Infants (6–12 months): 6–8 µg/kg/day

Children (1–5 years): 5–6 µg/kg/day

Children (6–12 years): 4–5 µg/kg/day

Adolescents: 2–4 µg/kg/day

Administration:

Given once daily, preferably in the morning

Tablets should be crushed and mixed with water or breast milk (not soy or formula)

Monitoring:

TSH and free T4 every 2–4 weeks initially

Every 3–6 months, once stable

Goal: Maintain T4 in the upper normal range and normalise TSH

B. Acquired Hypothyroidism (e.g., Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis)

Treatment indication:

Overt hypothyroidism (elevated TSH with low free T4)

Subclinical hypothyroidism with symptoms or TSH >10 mIU/L

Medication: Levothyroxine

Dosage:

Typically, 1–2 µg/kg/day, adjusted according to age and severity

Duration:

Often lifelong in autoimmune thyroiditis

2. Treatment of Hyperthyroidism in Children

A. Graves’ Disease (Most Common Cause)

1. Antithyroid Drugs (First-Line Therapy)

Preferred drug: Methimazole

(Propylthiouracil is avoided due to risk of severe liver toxicity)

Dosage:

Methimazole: 0.2–0.5 mg/kg/day

Maximum dose: 30–40 mg/day

[Given once or twice daily]

Duration:

Usually 12–24 months

Some children may require longer therapy

Monitoring:

Thyroid function tests every 4–6 weeks initially

Monitor for side effects (rash, agranulocytosis, liver dysfunction)

Common side effects:

Skin rash

Arthralgia

Rare but serious: neutropenia, hepatic toxicity

2. Beta-Blockers (Symptomatic Treatment)

Used to control adrenergic symptoms such as tachycardia, tremors, and anxiety.

Medication: Propranolol

Dosage:

0.5–2 mg/kg/day divided into 2–3 doses

Maximum: 40 mg per dose

Note:

Does not treat the underlying disease, but is used as supportive therapy.

3. Radioactive Iodine Therapy (RAI)

Indications:

Failure or intolerance of antithyroid drugs

Recurrent Graves’ disease

Older children and adolescents

Goal:

Ablation of thyroid tissue, leading to hypothyroidism

Post-treatment:

Lifelong levothyroxine replacement required

Not commonly used in very young children

4. Surgical Management (Thyroidectomy)

Indications:

Large goitre causing compression

Suspicion of malignancy

Drug-resistant hyperthyroidism

Post-operative care:

Lifelong levothyroxine

Monitoring for hypocalcemia and vocal cord injury

3. Treatment of Thyroid Nodules and Thyroid Cancer

A. Benign Thyroid Nodules

Observation with a regular ultrasound

Levothyroxine suppression therapy is not routinely recommended

B. Thyroid Cancer (Rare but More Aggressive in Children)

Treatment includes:

Total or near-total thyroidectomy

Radioactive iodine ablation (if indicated)

Lifelong levothyroxine at TSH-suppressive doses

Levothyroxine dosage (TSH suppression):

2–3 µg/kg/day, adjusted to maintain low TSH

4. Treatment of Subclinical Thyroid Disorders

Observation and regular monitoring

Treatment considered if:

Progressive TSH elevation

Presence of goitre or autoantibodies

Symptoms or growth delay

5. Long-Term Monitoring and Follow-Up

Regular assessment of growth parameters

Monitoring of pubertal development

Periodic thyroid function tests

Dose adjustment with growth and weight changes

Lifelong follow-up in most cases

OVERVIEW

Thyroid gland diseases constitute a significant proportion of endocrine disorders in the paediatric population and encompass a broad spectrum of conditions ranging from congenital hypothyroidism to acquired autoimmune thyroid diseases and, less commonly, thyroid nodules and malignancies. The thyroid gland plays a vital role in regulating growth, metabolism, and neurocognitive development; therefore, thyroid dysfunction during childhood can have profound and lasting effects if not identified and treated promptly.

Globally, congenital hypothyroidism remains one of the most common preventable causes of intellectual disability, emphasising the importance of neonatal screening programs. In older children and adolescents, autoimmune thyroid disorders—particularly Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Graves’ disease—are the predominant causes of thyroid dysfunction, with a marked female predominance. Epidemiological patterns vary widely across regions, influenced by iodine nutrition, genetic susceptibility, environmental exposures, and access to healthcare.

The clinical presentation of thyroid disease in children is often age-dependent and may be subtle, leading to delayed diagnosis. Advances in laboratory testing, imaging techniques, and standardised treatment guidelines have significantly enhanced disease detection and improved outcomes. Management strategies include pharmacological therapy (such as levothyroxine and antithyroid drugs), symptomatic treatment, radioactive iodine in selected cases, and surgical intervention when indicated. Lifelong monitoring is often required to ensure optimal growth, pubertal development, and quality of life.

CONCLUSION

Thyroid gland diseases in children represent a diverse group of disorders with significant implications for physical growth, neurodevelopment, and long-term health. Early diagnosis and timely intervention are crucial, particularly in congenital hypothyroidism, where prompt treatment can prevent irreversible neurological damage. Acquired thyroid disorders, especially autoimmune diseases, require individualised management and long-term follow-up to minimize complications and disease progression.

Effective treatment options are widely available and generally result in favourable outcomes when appropriately administered and monitored. However, challenges remain, particularly in resource-limited settings where screening and diagnostic facilities may be inadequate. Increased awareness among healthcare providers, implementation of universal newborn screening programs, and adherence to evidence-based treatment guidelines are essential to improving paediatric thyroid care globally.

Ongoing research is needed to better understand the genetic and environmental factors contributing to paediatric thyroid diseases and to optimise therapeutic strategies. A multidisciplinary approach involving paediatricians, endocrinologists, surgeons, and allied health professionals is key to achieving optimal outcomes for affected children.

REFERENCE

1. Léger J, Olivieri A, Donaldson M, et al. European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology consensus guidelines on screening, diagnosis, and management of congenital hypothyroidism. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2014;99(2):363–384.

2. De Groot LJ, Chrousos G, Dungan K, et al. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; Updated regularly.

3. American Academy of Pediatrics. Update of newborn screening and therapy for congenital hypothyroidism. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):2290–2303.

4. Rivkees SA, Stephenson K, Dinauer C. Adverse events associated with methimazole therapy of Graves’ disease in children. International Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology. 2010;2010:176970.

5. Brown RS. Autoimmune thyroid disease in childhood. Journal of Clinical Research in Pediatric Endocrinology. 2013;5(Suppl 1):45–49.

6. Wassner AJ, Brown RS. Hypothyroidism in infants and children. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2017;64(2):365–385.

7. Zimmerman D. Hyperthyroidism in children and adolescents. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 1990;37(6):1273–1295.

8. Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, et al. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2020.

9. Williams GR. Neurodevelopmental and neurophysiological actions of thyroid hormone. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2008;20(6):784–794.