"How do doctors know if a disease is truly occupational?"

Explore classification systems, diagnostic criteria, and medico-legal aspects of occupational diseases (clinical causation analysis, application of diagnostic criteria, legal documentation). Compare national policies on occupational health between two countries (United States and Germany) and propose improvements (literature search, policy analysis, critical thinking).

1. Dr. Turusbekova Akshoola Kozmanbetovna

2. Akhilesh Yadav

Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh state university, Kyrgyzstan

Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Kyrgyzstan

ABSTRACT

Establishing a definitive causal link between a work environment and a specific disease is a multi-dimensional challenge involving clinical diagnostics, epidemiological analysis, and legal frameworks. This report explores the classification systems (ILO, ICD-11) and clinical methodologies, such as the Bradford Hill criteria, used by medical professionals to determine work-relatedness. It details the specific diagnostic protocols for primary conditions, including occupational asthma, noise-induced hearing loss, and pneumoconiosis, while addressing the rigorous legal burden of proof and documentation required for compensation. A comparative analysis between the United States and Germany reveals divergent philosophies: Germany utilizes a structured, list-based system with extensive social insurance oversight, whereas the United States relies on a decentralized, individual-proof model. The report concludes by proposing strategic policy improvements for 2025 and beyond, emphasizing the integration of AI-driven case management, enhanced interprofessional teamwork, and the expansion of coverage to modern risks like mental health and remote work environments.

KEYWORDS -

Occupational Disease, Clinical Causation, Medico-legal Framework, Germany, United States, Diagnostic Criteria, ILO Classification, Workers' Compensation, AI in Healthcare, Public Health Surveillance.

INTRODUCTION

The determination of whether a disease is truly occupational represents a complex intersection of clinical medicine, epidemiology, and jurisprudence. For a physician, the diagnostic process transcends the mere identification of a pathological state; it involves an exhaustive investigation into the causal nexus between a specific work environment and the patient’s clinical presentation. This process is governed by internationally recognized classification systems and stringent diagnostic criteria that have evolved to address the inherent challenges of long latency periods and the multi-factorial nature of modern illnesses. The following analysis explores the mechanisms through which medical professionals establish work-relatedness, evaluates the frameworks used in the United States and Germany, and proposes strategic improvements to streamline these diagnostic and compensation systems.

Classification Systems and the Taxonomy of Occupational Harm

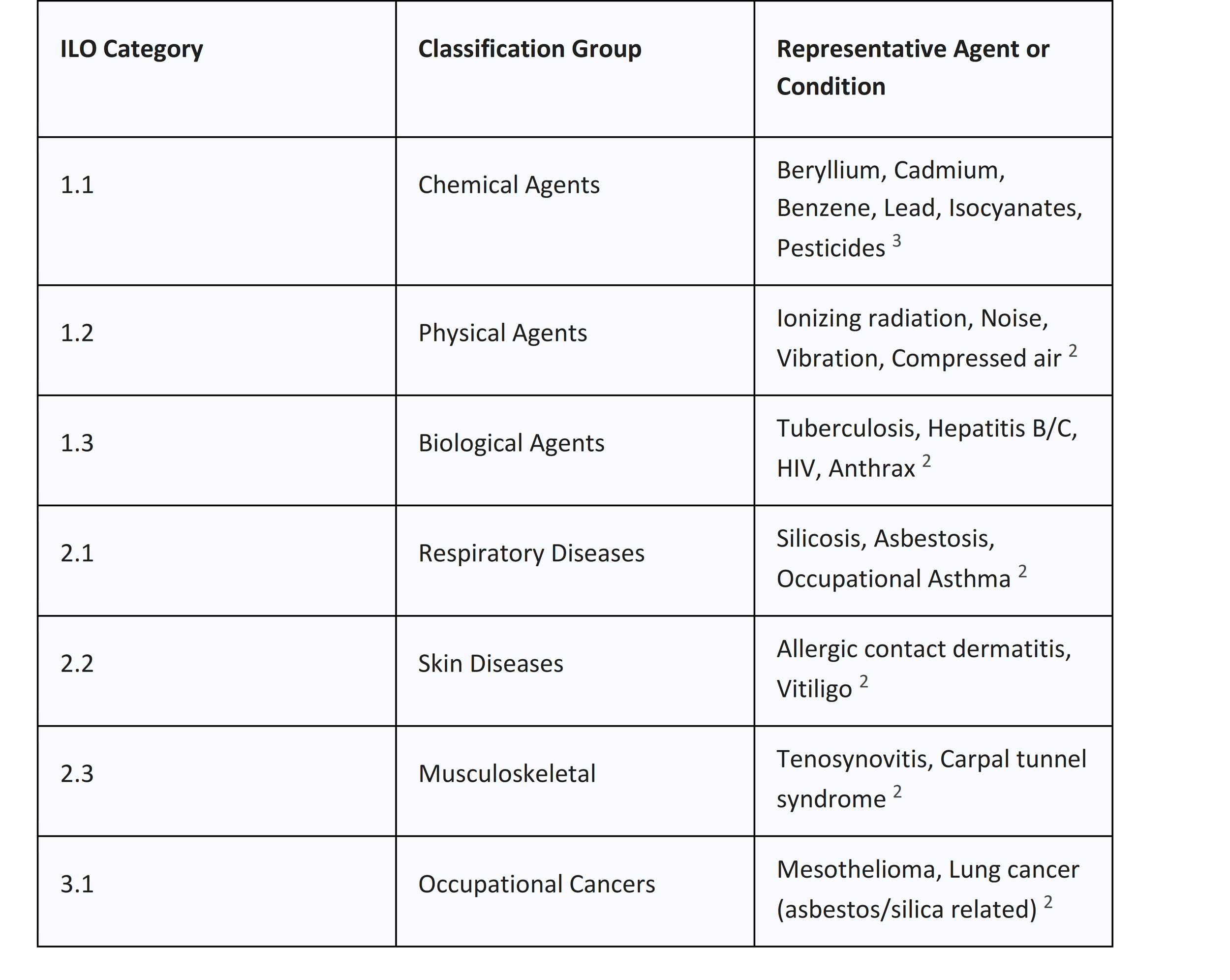

The foundation of occupational disease recognition lies in standardized classification systems that provide a common language for clinicians, regulators, and insurers. The International Labour Organization (ILO) maintains the most prominent framework, periodically revised to reflect advances in toxicology and occupational health. The 2010 revision of the ILO List of Occupational Diseases serves as a global model for national registries, categorizing illnesses into four distinct sections: diseases caused by exposure to agents arising from work activities, diseases described by target organ systems, occupational cancers, and a residual category for other recognized conditions.1

The ILO list is particularly comprehensive in its identification of chemical agents. It includes traditional toxins such as lead, mercury, and arsenic, alongside modern industrial compounds like isocyanates and acrylonitrile.2 By establishing a direct link between these agents and specific health outcomes, the ILO framework provides a presumption of work-relatedness that simplifies the diagnostic burden for physicians when clear exposure history is present. Complementary to the ILO list is the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), which has integrated occupational categories to enhance the precision of morbidity and mortality reporting.4 The ICD-11 reference guide provides specific codes for infectious diseases, malignant neoplasms, and even psychological conditions that arise "due to other conditions," often facilitating the alignment of clinical data with insurance and policy requirements.4

The Evolution of the ILO List

In 2010, the revised ILO list of occupational diseases was published, reflecting state-of-the-art development in the identification and recognition of these conditions. This revision was the result of two Meetings of Experts organized in 2005 and 2009, which established a worldwide consensus on diseases internationally accepted as being caused by work.1 The list is designed to assist countries in the prevention, recording, notification, and compensation of work-related illnesses.2

The list is subdivided into categories that allow for both agent-based and organ-based diagnosis. For example, Section 1 focuses on agents (chemical, physical, and biological), while Section 2 addresses diseases by organ system (respiratory, skin, musculoskeletal).1 This dual approach ensures that even if a specific causal agent is not immediately identified, the clinical manifestation in a target organ can still lead to a work-related investigation.

Interoperability with WHO ICD-11

The transition from ICD-10 to ICD-11 represents a significant evolution in healthcare data accuracy. ICD-11, adopted in 2019 and effective as of January 2022, provides a unified framework that enables policymakers to align healthcare initiatives globally.5 For occupational health, this means more precise coding for morbidity and mortality related to external causes.

ICD-11 includes specific extension codes for detailed clinical abstraction, which support the potential for AI and advanced analytics in identifying workplace disease trends.5 For example, the system now includes over 200 new codes for allergens, providing clinicians with greater diagnostic detail when managing occupational skin or respiratory conditions.5 This interoperability ensures that when a physician records a diagnosis of "Anaphylaxis due to external causes" or "Malignant neoplasms due to other conditions," the data can be seamlessly utilized for both clinical treatment and national health surveillance.4

Clinical Causation Analysis: The Bradford Hill Framework

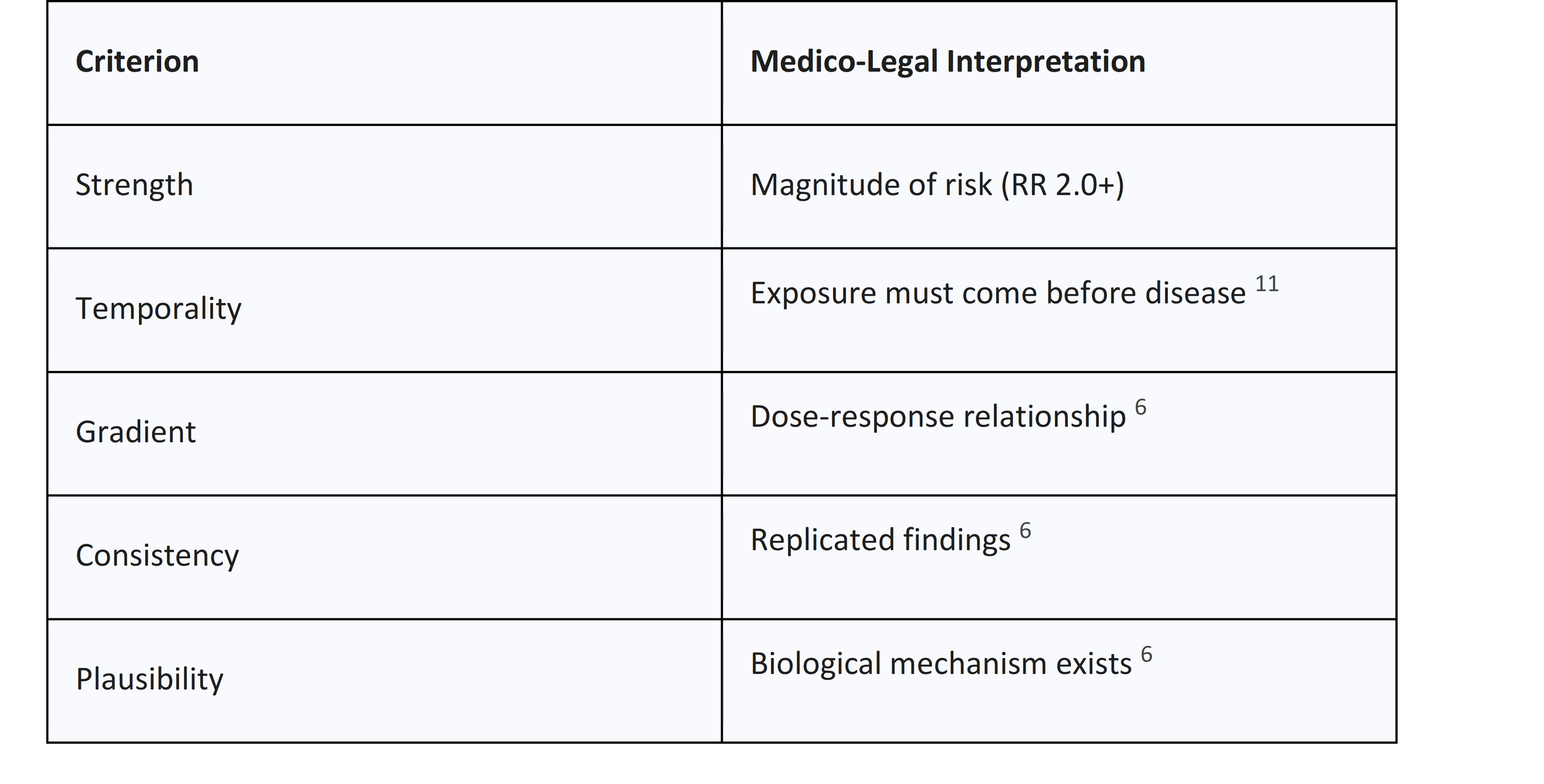

When a disease is not explicitly included on a national prescribed list, or when an individual case presents with confounding variables, physicians must apply a rigorous methodology for clinical causation analysis. The Bradford Hill criteria remain the gold standard for this assessment, providing nine viewpoints to evaluate human epidemiologic evidence and determine if a statistical association suggests a true causal relationship.8

The Nine Viewpoints of Association

The Bradford Hill criteria, published in 1965, help scientists determine whether the link between a triggering event and an outcome is indeed causal.6 These criteria are:

1. Strength of Association: A large association suggests the observed effect is less likely to be due to bias or confounding . For example, a risk ratio (RR) of 2 to 5 is often considered strong .

2. Consistency: Findings that are replicated across different researchers, populations, and clinical scenarios are more likely to be causal.6

3. Specificity: This refers to the degree to which an exposure leads to a single, specific effect rather than multiple outcomes .

4. Temporality: The cause must precede the effect. This is essential, particularly for diseases with long latency periods.11

5. Biological Gradient: A dose-response relationship where higher levels of exposure lead to a greater incidence or severity of disease.6

6. Plausibility: There must be a biological mechanism that explains how the agent causes the disease.6

7. Coherence: The causal conclusion should not conflict with the generally known facts of the natural history and biology of the disease.9

8. Experiment: Evidence obtained from experimental interventions can provide strong support for causation.6

9. Analogy: The existence of similar causal relationships with other agents or diseases provides further support.9

Applying Causation in the Clinic

In practice, a physician must synthesize these criteria to reach a level of "reasonable medical probability." This does not require absolute scientific certainty but rather a determination that the work environment was the prevailing factor—more than 50% likely—in causing the condition.11 This process requires a detailed review of medical, personal, family, and occupational history.

For example, when evaluating a case of leukemia potentially linked to radiation exposure, the clinician must determine the date of diagnosis and the specific period of employment at a covered facility to establish a valid claim. The use of Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) can further facilitate bias analysis, helping investigators highlight important variables that may influence the effect estimate.

Diagnostic Criteria for Primary Occupational Diseases

The application of diagnostic criteria varies significantly depending on the organ system affected. Respiratory conditions, hearing loss, and infectious diseases each require specific physiological and immunological testing to validate work-relatedness.

Occupational Asthma and Respiratory Conditions

Occupational asthma (OA) is a disease characterized by variable airflow limitation or airway hyperresponsiveness attributable to the workplace.14 A diagnosis of OA should not be made based on history alone but must be supported by physiological investigations.

1. Clinical History: The likelihood of an asthma diagnosis increases if symptoms include wheeze, breathlessness, chest tightness, and cough. Physicians must specifically ask if symptoms improve during weekends or holidays.16

2. Serial Peak Flow (PEF): At least four readings per day are required, at and away from work, for a period of at least three weeks. A serial record is suggestive of work-related asthma if there is a consistent fall in values or an increase in daily variability (approx. 20%) on workdays.

3. Immunological Testing: Specific IgE assays or skin-prick testing can identify causative agents with clear immunological mechanisms, particularly high-molecular-weight proteins.

4. Specific Inhalation Testing: Although the "gold standard," it is typically available only in specialized centers.

The severity of OA at diagnosis is often associated with the duration of symptoms before a formal diagnosis is reached. Studies have shown that workers with moderate-to-severe OA had symptoms for an average of 6.3 years compared to 3.4 years for those with mild disease, emphasizing the need for early diagnosis.10

Noise-Induced Hearing Loss (NIHL)

The diagnosis of NIHL is conducted by reviewing noise exposure history and audiograms. NIHL typically produces characteristic audiometric signatures: hearing is normal at low frequencies, followed by a sudden drop past 3000 Hz, most pronounced at 4000 Hz (the "4 kHz notch"), with a slight recovery at higher frequencies.

A 10 dB confirmed threshold shift from baseline at 2000, 3000, and 4000 Hz is the metric used by the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to determine a standard threshold shift. However, medical experts must also account for natural age-related declines in hearing. Current guidelines, such as the CLB and MLC guidelines, have varying false-positive rates (sometimes as high as 30%) because age-associated hearing loss can mimic NIHL patterns.

Pneumoconiosis and Black Lung Benefits

For coal-related occupational pneumoconiosis, the diagnostic requirements are rigid. Each clinical examination must include a chest X-ray interpreted by a NIOSH-certified "B" reader using the latest ILO Classification.18 Spirometric tests (FVC and FEV1) are also required to document pulmonary dysfunction.18

Interestingly, federal black lung eligibility in the US was extended to miners with disabling respiratory impairment even in the absence of radiographic evidence of pneumoconiosis.20 This recognition acknowledges that coal mine dust can cause severe lung disease that may not always present as classic opacities on an X-ray.21

Occupational Infectious Diseases

Infectious diseases pose substantial risks across various sectors. In Germany, data from 2018 to 2022 indicates that 71.5% of recognized infectious occupational diseases occurred in healthcare, welfare, or laboratories.22 Parasitic diseases (57%) and tuberculosis (35%) were the most frequent.22 Among zoonoses, Borrelia burgdorferi was the most common pathogen.22

Medico-Legal Frameworks: Burden of Proof and Documentation

The transition from clinical diagnosis to legal recognition involves a significant shift in the burden of proof. In an occupational disease claim, the responsibility rests on the injured worker to present sufficient evidence of the causal link between work and illness.24

The Standard of Proof

In the US, the claimant bears the burden of proving each criterion by a "preponderance of the evidence," meaning it is more likely than not that the proposition is true. For toxic exposure claims under the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act (EEOICPA), the standard is "at least as likely as not" that exposure was a significant factor in the illness.

Essential Documentation

To successfully prove a claim, the physician must provide a detailed medical report that follows specific workers' compensation rules.13 This documentation must include:

● Diagnosis and Date of Diagnosis: Crucial for determining if the illness is related to employment at a specific covered facility.

● Detailed Description of Job Tasks: To identify potential hazards such as repetitive motion or chemical exposure.

● Direct Link to Job: The doctor must clearly explain how the work environment caused or aggravated the condition.13

● Objective Diagnostic Test Results: Scans (X-rays, MRIs), blood work, and physiological test data.26

A "worn out back" or dermatitis can be considered occupational diseases if work was a substantial factor in aggravating a pre-existing condition.28 In these cases, medical evidence must demonstrate that the workplace incident significantly contributed to the illness beyond its normal progression.26

The Appeals Process

In the US, the Employees' Compensation Appeals Board (ECAB) is an independent appellate body with jurisdiction over final adverse decisions by the Office of Workers' Compensation Programs (OWCP).30 The Board performs a de novo review of the record but is precluded from reviewing any evidence that was not before the OWCP at the time of the final decision . Appeals must be filed within 180 days.30

National Policies: A Comparison of Germany and the United States

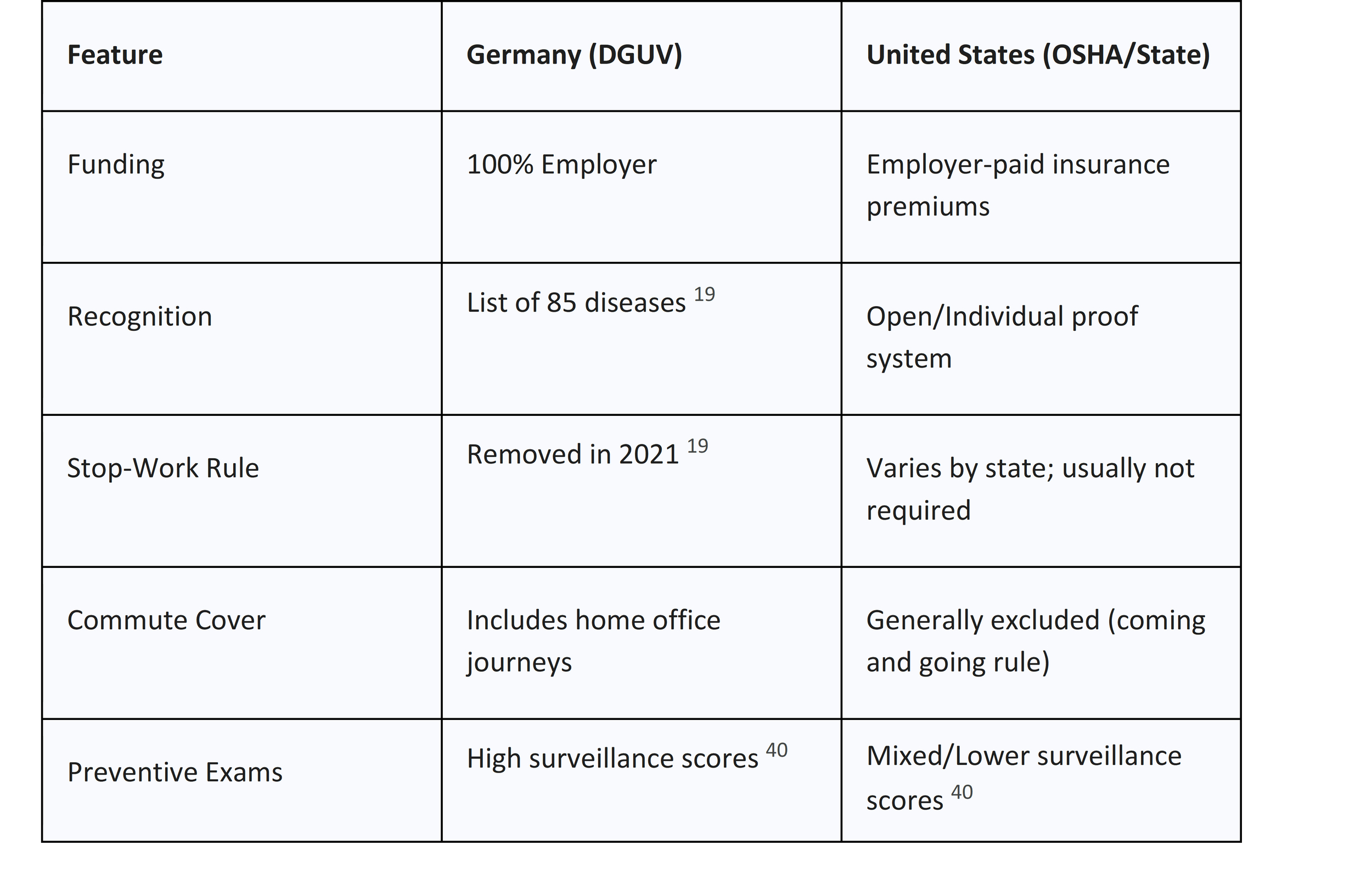

The systems for recognizing and compensating occupational diseases in Germany and the United States represent two distinct philosophies of social insurance and regulation.

Germany: The Dual System and the DGUV

The German Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) system is characterized by a "Dual System" involving federal legislation and statutory accident insurance regulation.33 The German Social Accident Insurance (DGUV) is the umbrella association for these organizations, representing around 70 million insured people.29

● Funding: Statutory accident insurance is financed exclusively by employers.

● The List Principle: Germany has a list of formally recognized occupational diseases (currently 85).35 If a disease meets the criteria on the list, there is a presumption of work-relatedness.36 However, other diseases can be recognized if new medical/scientific findings meet the criteria for inclusion.35

● Modernization (2021): A major reform at the turn of 2020/2021 removed the "forced obligation to stop working".19 Previously, workers had to give up the job that caused their illness to receive recognition. Now, the focus is on "individual prevention," where insurance funds specific measures to mitigate risks at the workplace so the employee can remain in their role.19

● Commuting and Home Office: German law also covers "insured routes to work." A recent Federal Social Court decision clarified that the journey from bed to a home office is a covered route, strengthening protection for remote workers.

The United States: Decentralized and Proof-Oriented

The US system is decentralized, with federal and state laws varying widely. Workers' compensation is generally viewed as an "exclusive remedy," although this principle is facing increased legal scrutiny.

● Structure: OSHA sets regulatory standards, while the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) manages OSH data.38 Recognition and compensation are handled through a mix of private insurance, state funds, and federal programs.

● The System of Proof: Unlike the rigid lists of many European countries, the US typically uses an "open system" where any disease can be compensated if a causal link to work is proven. While this allows for more flexibility, it places a higher burden on the worker to fight for recognition in a potentially adversarial system.

● Medical Standards Comparison: A comparative study of OSHA standards versus German guidelines for preventive health examinations found that German requirements consistently ranked higher for quality control, screening, and surveillance.40

Challenges in Occupational Disease Recognition

Several structural and biological factors impede the accurate and timely recognition of occupational diseases, leading to significant undercounting in national statistics.

Latency Periods and Multi-factorial Attribution

Unlike injuries, which are immediate events, occupational diseases often have long latency periods.41 For example, lung cancer can take decades to develop after exposure to asbestos or silica.15 Because many diseases are multi-factorial—influenced by smoking, genetics, and non-work factors—workers' compensation data tends to under-represent the actual incidence of disease.

The Diagnostic "Blind Spot"

The National Academy of Medicine (NASEM) described diagnostic errors as a "blind spot" in healthcare.39 Most people will experience at least one diagnostic error in their lifetime, and the complexity of work-related diseases only increases this risk.43 Errors are often linked to a lack of teamwork among clinicians, pathologists, and radiologists, as well as limited patient engagement in the diagnostic process.44

Data Gaps in Surveillance

The BLS acknowledges that work-related illnesses are undercounted because it is difficult to match an illness to a specific work exposure years later.38 Statutory reporting by employers is often poor, and while some countries use multiple data sources (like hospital and mortality records), no "ideal" system exists.

Proposed Improvements for National Occupational Health Policies

To address the documented deficiencies in both the US and German systems, a series of strategic improvements are proposed based on current literature and policy analysis.

1. Modernization of Case Management through AI and Digital Platforms

State and federal governments should prioritize the modernization of workers' compensation case management. Moving toward a "Unified, Intelligent Platform" can reduce fragmentation in medical documentation.27

● AI-Enabled Insights: AI can be used to identify trends that lead to risk mitigation by analyzing "veracity" and "variety" of high-quality data over time.42 This can help detect fraud and provide real-time decision support for fair outcomes.27

● Digital Quality Measurement: Transitioning to digital quality measurement can reduce the data collection burden on clinicians while increasing the use of available data to help prevent medical errors.46

2. Strengthening Team-Based Diagnosis and Patient Engagement

To reduce diagnostic error, the diagnostic process must be viewed as a team-based activity.44

● Collaborative Care: Facilitate cooperation between treating physicians, radiologists, and specialists (like B-readers).44

● Patient Feedback: Organizations should create environments where patients and their families feel comfortable sharing feedback and concerns about potential diagnostic near misses.44 Access to clinical notes and electronic health records (EHRs) is vital for patients to review their data for accuracy.44

3. Expanding the Scope of Occupational Health to Modern Risks

National policies must evolve to cover emerging threats in the 2025 workforce landscape .

● Aging Workforce: With the rise in claims among workers aged 60 and older, training and assistive technologies must be tailored to reduce physical strain .

● Mental Health Parity: While only 2% of claims currently involve a mental health component, these claims are significantly more expensive and last longer . Early intervention—such as engaging behavioral health specialists within the first 90 days—can reduce temporary total disability (TTD) days by 40% .

● Home Office Protection: Other nations should consider the German model of extending accident insurance to the home office to reflect the reality of modern remote work .

4. Implementing Proactive Medical Surveillance and Registries

Relying on compensation claims for data is insufficient.

● Disease Registries: Countries should develop national disease registries and public health surveillance systems that are independent of compensation boards to support policy evaluation.32

● Post-Exposure Monitoring: For known carcinogens (like asbestos), mandated follow-up for exposed workers can lead to earlier detection and shortened "Total Interval Time to Diagnosis" (TITD).15

5. Policy Interventions and Research

Finally, there is a need for "Intervention Research" to evaluate the effectiveness of OHS policies.32 Policies should be designed to be minimally burdensome to employers while maximizing hazard reduction. This includes streamlining the coverage review process for new medical technologies to ensure workers have access to state-of-the-art care.46

Conclusion

The determination of a disease's occupational status is a rigorous clinical and legal undertaking. While the ILO and WHO provide a robust global taxonomy, the practical application of these standards remains a challenge due to the multi-factorial nature of disease and the inherent limitations of national insurance systems. Germany’s centralized, list-based approach offers high standards of surveillance and has recently pivoted toward a progressive "individual prevention" model. In contrast, the US system’s decentralized, proof-oriented structure provides flexibility but often results in significant data gaps and lower surveillance scores.

The future of occupational health lies in the convergence of clinical medicine and big data. By modernizing case management with AI, fostering interprofessional teamwork, and expanding coverage to include mental health and remote work risks, national health systems can move from a reactive model of compensation to a proactive model of prevention and health promotion. The ultimate goal is to ensure that the global working population benefits from a system where "no one's health should be harmed as a result of their work".34

References

1. ILO Diagnostic and exposure criteria for occupational diseases ..., accessed January 11, 2026, https://ldoh.net/news/ilo-diagnostic-and-exposure-criteria-for-occupational-diseases/

2. List of occupational diseases (revised 2010) - International Labour Organization, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/media/336021/download

3. ILO List of Occupational Diseases - International Labour Organization, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/media/336656/download

4. International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics Reference Guide - World Health Organization (WHO), accessed January 11, 2026, https://icdcdn.who.int/icd11referenceguide/en/refguide.pdf

5. International Classification of Diseases (ICD) - World Health Organization (WHO), accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases

6. Bradford Hill criteria – Knowledge and References - Taylor & Francis, accessed January 11, 2026, https://taylorandfrancis.com/knowledge/Medicine_and_healthcare/Epidemiology/Bradford_Hill_criteria/

7. Assessing causality in epidemiology: revisiting Bradford Hill to incorporate developments in causal thinking - PMC - NIH, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8206235/

8. Applying the Bradford Hill Criteria for Causation to Repetitive Head Impacts and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy - Frontiers, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neurology/articles/10.3389/fneur.2022.938163/full

9. Applying the Bradford Hill criteria in the 21st century: how data integration has changed causal inference in molecular epidemiology | springermedizin.de, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.springermedizin.de/applying-the-bradford-hill-criteria-in-the-21st-century-how-data/9769658

10. Factors associated with severity of occupational asthma with a latency period at diagnosis, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2668791/

11. Epidemiological Evidence In Occupational Injury Cases - Wisconsin Civil Trial Lawyers, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.pittslaw.com/content/epidemiological-evidence-in-occupational-injury-cases/

12. Occupational Diseases | Missouri Department of Labor and Industrial Relations, accessed January 11, 2026, https://labor.mo.gov/dwc/injured-workers/occupational-diseases

13. What Is an Occupational Disease and How Do You Prove It in a Workers' Comp Claim?, accessed January 11, 2026, https://orlowlaw.com/what-is-an-occupational-disease/

14. Guidelines for Occupational Asthma, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.archbronconeumol.org/es-download-pdf-S1579212906605697

15. Neglected Occupational Risk Factors—A Contributor to Diagnostic Delays in Lung Cancer, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/14/1/106

16. Concise guidance: diagnosis, management and prevention of ... - NIH, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4954103/

17. Noise-Induced Hearing Loss - MDPI, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/12/6/2347

18. 342.316 Liability of employer and previous employers for occupational disease -- Claims procedure -- Administrative regulation, accessed January 11, 2026, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=47621

19. A Social Achievement Turns 100 - DGUV, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.dguv.de/en/mediencenter/pm/presse_detail_en_655494.jsp

20. Pneumoconiosis ICD-CM Diagnosis Codes on Medicare Claims for Federal Black Lung Program Beneficiaries - CDC Stacks, accessed January 11, 2026, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/223564

21. Pneumoconiosis ICD-CM Diagnosis Codes on Medicare Claims for Federal Black Lung Program Beneficiaries - PMC - NIH, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7732031/

22. Analysis of recognized occupational infectious diseases in Germany between 2018 and 2023 - PubMed, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40662956/

23. German Court Rules Occupational Accidents at Home May Be Covered by Statutory Accident Insurance - Ogletree, accessed January 11, 2026, https://ogletree.com/insights-resources/blog-posts/german-court-rules-occupational-accidents-at-home-may-be-covered-by-statutory-accident-insurance/

24. Burden of Proof | U.S. Department of Labor, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/owcp/energy/regs/compliance/Decisions/GenericDecisions/Headnotes/DecisionBurdenOfProof

25. The European influence on workers' compensation reform in the United States - PMC, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3267658/

26. Medical Evidence in Workers' Compensation Claims - LawInfo.com, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.lawinfo.com/resources/workers-compensation/medical-evidence-in-workers-compensation-claims.html

27. Why Modernizing Workers' Compensation Case Management Is a Priority for State Governments in 2025 - Speridian Technologies, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.speridian.com/blogs/why-modernizing-workers-compensation-case-management-is-a-priority-for-state-governments-in-2025/

28. Occupational Injury or Disease Under Workers Compensation – PittsLaw - Wisconsin Civil Trial Lawyers, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.pittslaw.com/content/occupational-injury-or-disease-under-workers-compensation-law/

29. German Social Accident Insurance, DGUV, Germany - Public Health - European Commission, accessed January 11, 2026, https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/aff62147-70fb-4d9c-b08c-f572928dbb14_en?filename=cons_ern_health_insurer_co01_dguv_germany_en.pdf

30. ECAB - Processing an Appeal | U.S. Department of Labor, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ecab/resources/appeals

31. Employees' Compensation Appeals Board | U.S. Department of Labor, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ecab/about/background

32. (PDF) Improving OHS Policy Through Intervention Research - ResearchGate, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267969747_Improving_OHS_Policy_Through_Intervention_Research

33. The National Profile of the Occupational Safety and Health System ..., accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@safework/documents/policy/wcms_186995.pdf

34. In good hands, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.bgrci.de/fileadmin/BGRCI/Banner_und_Artikelbilder/Presse_und_Medien/Publikationen/dguv-ingutenhaenden-eng.pdf

35. Occupational diseases - DGUV, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.dguv.de/en/benefits/occupational_diseases/index.jsp

36. An international comparison of occupational disease and ... - GOV.UK, accessed January 11, 2026, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7d84afed915d3fb9594400/InternationalComparisonsReport.pdf

37. Navigating workers' compensation in 2025: four hot topics shaping the future | Sedgwick, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.sedgwick.com/blog/navigating-workers-compensation-in-2025-four-hot-topics-shaping-the-future/

38. Counting injuries and illnesses in the workplace: an international ..., accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2017/article/pdf/counting-injuries-and-illnesses-in-the-workplace.pdf

39. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. | PSNet, accessed January 11, 2026, https://psnet.ahrq.gov/issue/improving-diagnosis-health-care

40. Comparison of US Occupational Safety and Health Administration ..., accessed January 11, 2026, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9093650/

41. Occupational Disease Indicators 2014 - Safe Work Australia, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1702/occupational-disease-indicators-2014.pdf

42. Advancing safety analytics: A diagnostic framework for assessing system readiness within occupational safety and health - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10191184/

43. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care (2015) - National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/21794/chapter/3

44. Summary - Improving Diagnosis in Health Care - NCBI Bookshelf, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK338586/

45. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care (2015) - National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/21794/chapter/2

46. Quality in Motion - CMS, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.cms.gov/files/document/quality-motion-cms-national-quality-strategy.pdf