"How do doctors know if a disease is truly occupational?"

Explore classification systems, diagnostic criteria, and medico-legal aspects of occupational diseases (clinical causation analysis, application of diagnostic criteria, legal documentation). Compare national policies on occupational health between two countries (France and U.K.) and propose improvements (literature search, policy analysis, critical thinking).

1. Dr. Turusbekova Akshoola Kozmanbetovna

2. Virochan Kumar Giri

(Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh state university, Kyrgyzstan

Student, International Medical Faculty, Osh State University, Kyrgyzstan)

Abstract

The identification of a disease as truly occupational is a sophisticated process that bridges clinical medicine, epidemiology, and legal jurisprudence. This report explores the mechanisms by which medical practitioners navigate the complexities of work-relatedness, moving from the initial clinical suspicion to a formalized legal recognition. It examines the foundational classification systems, including the World Health Organization’s ICD-11 and the International Labour Organization’s list of occupational diseases, which provide the standardized terminology necessary for global health surveillance and social insurance. The report provides an in-depth analysis of clinical causation, focusing on the application of the Bradford Hill criteria and the Injury Causation Analysis (ICA) protocol to distinguish between competing and combined etiologies. A rigorous comparison of national policies between France and the United Kingdom reveals divergent philosophies: France’s system is built upon the "presumption of origin" and the theory of professional risk, while the United Kingdom employs a more administrative, risk-based "no-fault" scheme with higher disability thresholds. Furthermore, the analysis identifies significant cognitive biases and structural barriers that contribute to the chronic underreporting of occupational illnesses. Finally, the report proposes a series of evidence-based improvements, including the adoption of a structured six-step diagnostic approach and the expansion of sentinel surveillance networks to better capture emerging risks in the modern workforce.

Keywords: Occupational Disease, Clinical Causation, ICD-11, Bradford Hill Criteria, France, United Kingdom, Medico-Legal Documentation, Presumption of Origin, Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit.

1. The Foundations of Occupational Health and Disease Identification

The identification of an occupational disease is distinguished from general clinical diagnosis by the necessity of establishing a direct, causal link between the patient’s health condition and their professional environment. Unlike industrial accidents, which are defined as sudden, discrete events occurring at a specific time and place, occupational diseases often manifest with a significant temporal lag, or latency period, following prolonged exposure to hazardous agents.1 This latency can span decades, particularly in cases of occupational cancers such as mesothelioma or silicosis, making the reconstruction of a patient’s work history a forensic as much as a medical exercise.4

At its core, an occupational disease is any health condition caused primarily by exposure to risk factors arising from work activities.6 However, the multifactorial nature of common conditions—such as musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), cardiovascular diseases, and mental health conditions—means that the work environment is often one of several contributing factors. The medical practitioner’s primary challenge is therefore to determine whether the occupational component is "substantial" or "primary" enough to satisfy the legal definitions of work-relatedness within a given jurisdiction.2

The evolution of occupational health has seen a shift from the recognition of acute toxicities, such as lead or mercury poisoning, to a more nuanced understanding of chronic stressors, including ergonomic strain, psychosocial risks, and complex chemical exposures. As the global economy transitions toward digital and "green" jobs, new risks—such as those associated with nanomaterials or unconventional working hours—require medical practitioners to remain abreast of rapidly evolving classification systems and diagnostic criteria.8

2. Global Classification Systems and Standardized Diagnostic Criteria

The ability of doctors to recognize and report occupational diseases depends heavily on standardized classification systems. These frameworks ensure that clinical findings are translated into a language that is recognized by insurers, regulators, and researchers across different countries.

2.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) and ICD-11

The release of the 2025 edition of the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11), marks a significant advancement in the documentation of occupational health.11 ICD-11 is designed for high digital interoperability, utilizing FHIR APIs and natural language processing to integrate clinical data into national health information systems.11 For the occupational physician, ICD-11 offers approximately 17,000 diagnostic categories and 130,000 clinical terms, allowing for the precise coding of not only the disease itself but also the external causes and context of the exposure.11

In the ICD-11 framework, practitioners can flag conditions for occupational relevance. This means a physician can code a primary diagnosis, such as "occupational asthma," while simultaneously adding descriptors for the specific site of activity, the functional impact, and the nature of the exposure (e.g., isocyanates or wood dust).12 This granular level of detail is vital for the development of evidence-based policies and the evaluation of workplace health interventions.10

2.2 The International Labour Organization (ILO) List of Occupational Diseases

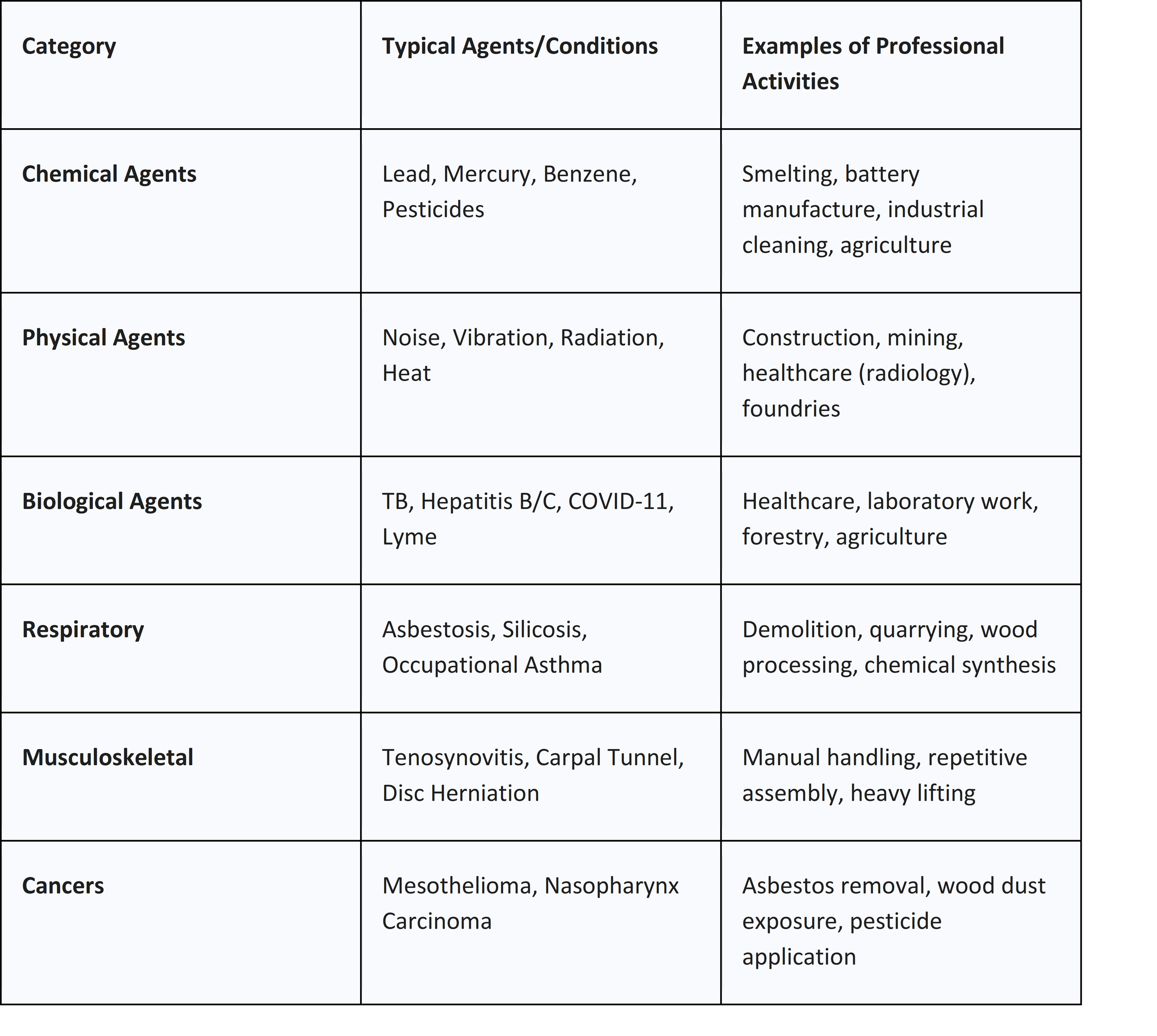

The ILO list of occupational diseases serves as a template for national compensation systems worldwide. Approved by the ILO Governing Body, the most recent iterations include 106 recognized items categorized by the nature of the hazard.13 These include:

● Chemical Agents: Ranging from heavy metals like lead and mercury to complex organic solvents, pesticides, and asphyxiants like carbon monoxide.14

● Physical Agents: Including noise-induced hearing loss, vibration-induced disorders, and diseases caused by ionizing radiation or extreme temperatures.14

● Biological Agents: Such as tuberculosis, hepatitis, and, as of the 2022 recommendation update, COVID-19 when contracted in high-risk sectors like health and social care.9

● Organ-System Diseases: Focused on specific clinical outcomes like occupational cancers, skin diseases, and respiratory disorders.13

The ILO list is not merely a statistical tool; it establishes the international exposure and diagnostic criteria necessary for early detection.13 For example, the criteria for recognizing a disease caused by pesticides (Item 1.1.36) require clear evidence of exposure during work activity coupled with characteristic clinical signs of intoxication.14

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Major Occupational Disease Groupings

3. The Clinical Diagnostic Framework: Analyzing Causation

The transition from a clinical diagnosis to an occupational recognition requires a rigorous analysis of causation. Medical practitioners must distinguish between medical causation (based on scientific criteria and biological plausibility) and legal causation (determined by jurisdictional authority).2

3.1 The Bradford Hill Criteria in Occupational Medicine

The Bradford Hill criteria remain the gold standard for evaluating whether an observed association between a workplace exposure and a disease is likely to be causal.20 These nine viewpoints allow the physician to move beyond simple correlation:

1. Strength of Association: A high risk ratio (e.g., 2 to 5) suggests that the relationship is less likely to be explained by confounding factors.21

2. Consistency: The same association should be observed across different researchers, populations, and clinical scenarios.20

3. Specificity: Ideally, the exposure leads to a specific disease, such as the unique link between asbestos and mesothelioma.21

4. Temporality: The exposure must precede the outcome. This is the only absolute requirement in the criteria.5

5. Biological Gradient: A dose-response relationship where increased intensity or duration of exposure results in a higher rate or severity of disease.20

6. Biological Plausibility: The existence of a credible physiological or pathological mechanism that explains how the agent causes the disease.20

7. Coherence: The causal interpretation should not conflict with the known natural history of the disease.21

8. Experiment: Clinical or environmental interventions (e.g., removing a worker from an allergen) that lead to an improvement in health status.20

9. Analogy: Drawing parallels from the effects of similar chemical or physical agents.20

In individual clinical evaluations, practitioners often emphasize the criteria of temporality, strength of association, and biological plausibility.5 For instance, in evaluating occupational asthma, the physician looks for a clear temporal pattern where symptoms worsen during work shifts and improve during absences.5

3.2 Injury Causation Analysis (ICA) and Biomechanics

For musculoskeletal or traumatic injuries, practitioners employ the Injury Causation Analysis (ICA). This scientific method analyzes the mechanism and magnitude of injury by comparing the mechanical forces involved in a workplace incident with the human body's tolerance levels.5 The ICA protocol typically involves three critical steps:

● Biomechanics Assessment: Analyzing how the worker interacted with their surroundings (e.g., the posture during a lift) to determine the forces acting on specific joints or tissues.5

● Literature Review: Identifying whether the described forces are capable of causing the specific injury noted in the medical records.5

● Hypothesis Testing: Comparing the expected clinical findings with the objective data from physical examinations and imaging studies.5

This rigorous approach prevents "diagnostic momentum," where an initial, potentially subjective label (such as "work-related back pain") is carried forward without independent validation of the mechanism of injury.5

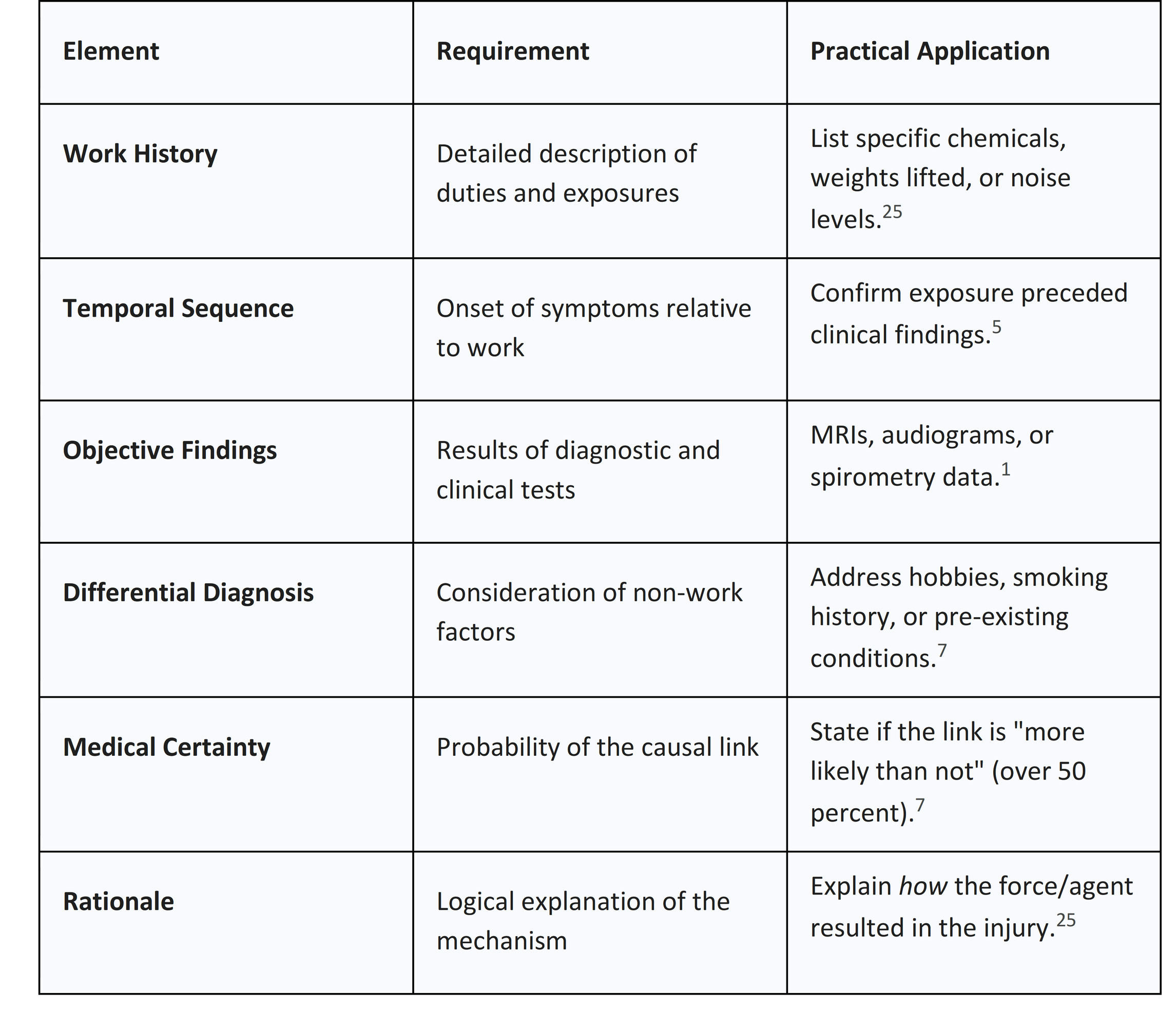

Table 2: The Checklist for a Comprehensive Causation Report

4. Medico-Legal Jurisprudence in France: The Tableaux System

France’s occupational health system is governed by a long-standing commitment to the "theory of professional risk" (théorie du risque professionnel), which emphasizes social solidarity and employer responsibility without the need to prove fault.29

4.1 The Presumption of Origin

The cornerstone of the French system is the "presumption of origin." Article L.461-1 of the Social Security Code establishes that any disease meeting the criteria of an official "Tableau" is systematically presumed to be of occupational origin.3 For the worker, this removes the burden of proving a causal link; they need only demonstrate that their condition satisfies three specific criteria outlined in the table:

1. Clinical Symptoms: The specific pathological lesions or symptoms required (e.g., "ataxie cérébelleuse" for mercury poisoning).3

2. Latency Period (Délai de prise en charge): The maximum time allowed between the end of exposure and the diagnosis.3

3. Occupational Exposure: A list of works or professional tasks known to expose the worker to the risk.18

The French system currently maintains 121 tables for the general social security scheme and 66 for the agricultural scheme.3 This system is "pragmatic" and "closed," but it ensures a high level of protection for conditions that have been scientifically validated as occupational risks.34

4.2 The CRRMP and Off-Table Recognition

For conditions that do not meet all table criteria, or for off-list diseases, France utilizes a "mixed" system through the Regional Committees for the Recognition of Occupational Diseases (CRRMP).3 The CRRMP assesses cases on an individual basis to determine if the disease was "essentially and directly" caused by the worker’s usual professional activity.3

For diseases not listed in any table, there is a severity threshold: the condition must have caused the worker's death or resulted in a permanent incapacity rate (IPP) of at least 25 percent.3 Recent data from 2024 indicates that the CRRMP has seen a significant increase in the recognition of psychosocial risks, such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, which are typically managed as off-table cases.17

5. Medico-Legal Jurisprudence in the United Kingdom: The IIDB Scheme

In contrast to the highly regulated and protective French model, the United Kingdom’s approach to occupational health is more administrative and risk-based.30 The Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit (IIDB) is a non-contributory, no-fault benefit provided by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP).1

5.1 The Prescribed Diseases and Occupational Criteria

In the UK, a disease is only eligible for compensation if it is one of over 70 "prescribed diseases" listed in the regulations.1 For a disease to be prescribed, there must be a consensus that it is a recognized risk of specific occupations and that the link to work can be established with reasonable certainty in individual cases.1 These diseases are divided into four categories:

● Group A (Physical): Such as occupational deafness and vibration white finger.1

● Group B (Biological): Including infections like anthrax or hepatitis.

● Group C (Chemical): Such as poisoning by mercury, lead, or organic solvents.

● Group D (Miscellaneous): Focusing on respiratory conditions like asbestosis, silicosis, and occupational asthma.1

5.2 The Role of the Medical Advisor and Disablement Thresholds

The diagnostic process in the UK is heavily reliant on the "medical advisor"—an experienced practitioner specifically trained in industrial injuries.1 During an IIDB assessment, the doctor evaluates:

1. Diagnosis: Whether the claimant is suffering from the prescribed disease as defined in the rules.1

2. Causation: Whether the disease is due to the nature of the "employed earner’s employment".1

3. Degree of Disablement: A percentage assessment (0-100 percent) comparing the claimant’s condition with a healthy person of the same age and sex.1

A critical feature of the UK system is the disability threshold. Typically, a claimant must be assessed as at least 14 percent disabled to receive the benefit.39 This is a markedly higher requirement than the 1 percent threshold used in France for many listed diseases, contributing to the UK’s lower overall expenditure on occupational disease benefits as a proportion of GDP.33

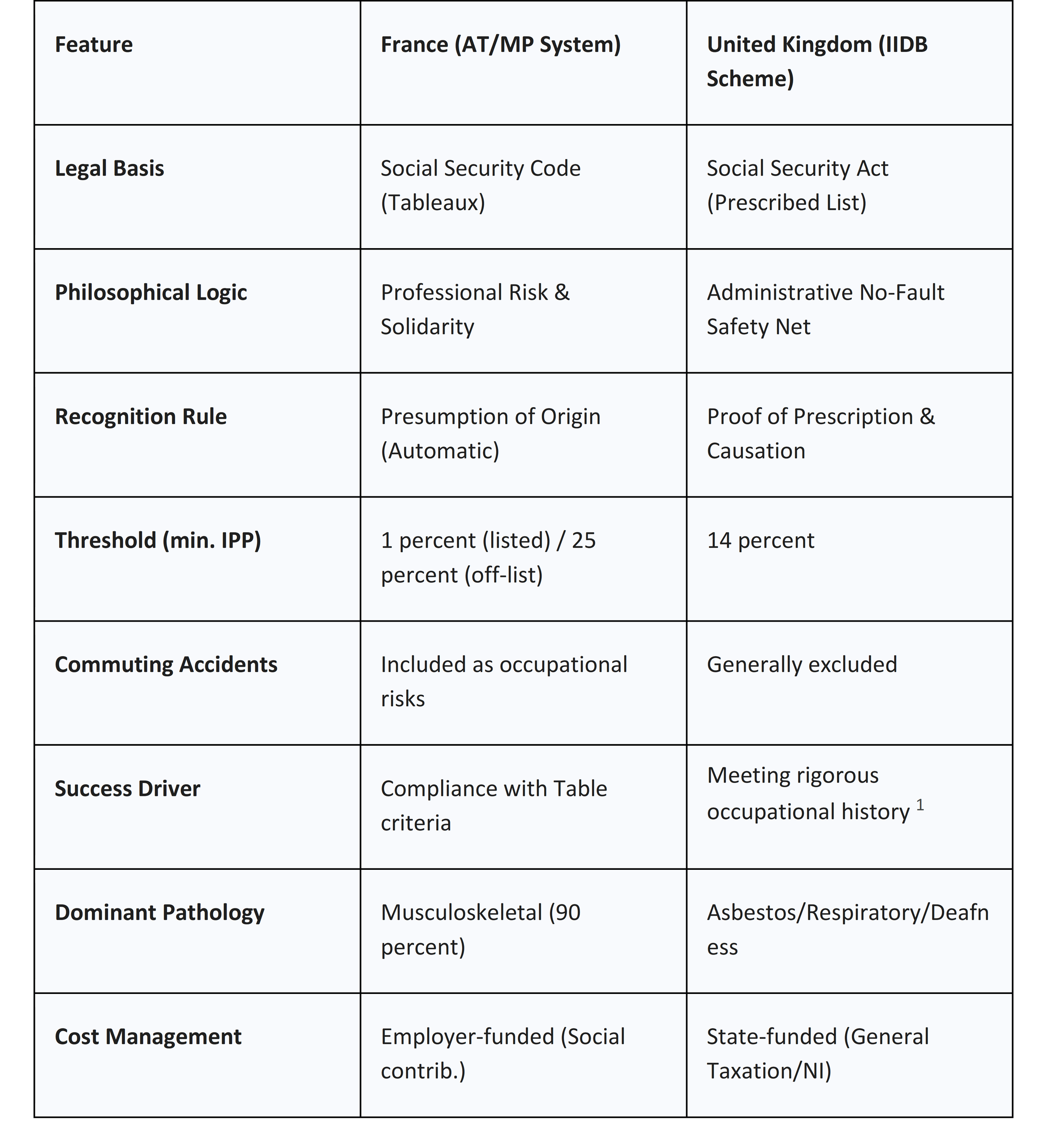

6. Comparative Synthesis: Policy Analysis and Success Rates

The divergent philosophies between France and the UK manifest in the statistics and the types of diseases recognized. France’s system, prioritizing solidarity, results in a high volume of recognized musculoskeletal disorders, while the UK’s system, prioritizing a risk-based administrative safety net, focuses more on severe industrial injuries and specific respiratory conditions.29

6.1 Recognition Rates and Statistical Trends

In 2024, the French AT/MP branch reported a 6.7 percent increase in recognized occupational diseases, with musculoskeletal disorders accounting for approximately 90 percent of all cases.35 This high recognition rate is attributed to the strong "presumption of origin" and the low (1 percent) compensation threshold.33 Furthermore, France compensates pleural plaques from asbestos exposure based on certification alone, whereas many other countries require functional impairment for compensation.33

The UK, conversely, reports lower rates of work-related ill health in many European comparisons.43 While the UK has high standards for workplace fatal injury prevention (0.61 per 100,000 workers), its recognized occupational disease caseload is constrained by the 14 percent disability requirement and a narrower list of prescribed conditions.33 Data from 2023-2024 shows that while UK health-related benefit claims have surged post-pandemic, much of this is driven by general disability (PIP) rather than specifically recognized occupational disease claims (IIDB).44

Table 3: Systemic Comparison of France and the United Kingdom

6.2 The Trade-off: Safety vs. Cost

A critical insight from the literature suggests that the UK explicitly frames its health and safety regulation as a trade-off between safety and cost, codified in the principle of "so far as is reasonably practicable" (ALARP).30 This neoliberal risk-taking approach contrasts with the French "precautionary" model, where the legal requirement for worker safety is often unqualified.30 Interestingly, despite these differences in statutory goals, the UK’s fatal injury rates remain lower than France’s (6 per million vs. 26 per million), suggesting that a focus on risk-based prevention can be as effective as a focus on universal compensation.30

7. Barriers to Identification: Cognitive Biases and Reporting Flaws

The clinical and administrative recognition of occupational diseases is fraught with potential errors. Both individual practitioners and broader reporting systems are susceptible to biases that lead to the significant underreporting noted by numerous researchers.6

7.1 Cognitive Biases in Occupational Diagnosis

Occupational physicians are prone to mental shortcuts that can impair judgment and result in misdiagnosis or flawed fitness-for-duty decisions.24 Seven critical biases have been identified:

1. Anchoring Bias: Giving undue weight to the first piece of information received, such as a patient’s initial symptom description or a prior diagnosis of "sciatica," while ignoring contradictory workplace evidence.24

2. Confirmation Bias: Actively seeking information that confirms a pre-existing belief (e.g., that a worker is exaggerating for gain) while dismissing objective clinical findings.24

3. Availability Heuristic: Overestimating the likelihood of a condition because a similar, compelling case was recently seen (e.g., suspecting occupational asthma in every worker after one severe case).24

4. Attribution Bias: Attributing a worker's complaints to their personality or "character" rather than exploring occupational stressors or medical factors.24

5. Diagnostic Momentum: Carrying forward an existing diagnosis from an ER or GP without independent validation.24

6. Framing Effect: Being influenced by how an employer presents a case (e.g., describing an employee as "unmotivated") before the medical examination begins.24

7. Overconfidence Bias: Relying on intuition rather than structured evidence-based protocols, leading to the omission of necessary diagnostic tests.24

7.2 Structural Limitations and Information Bias

Beyond cognitive bias, structural factors contribute to unreliable statistics. Information bias often arises from "measurement error" or "misclassification" of exposures.4 In cohort and case-control studies, recall bias occurs when diseased participants report their past exposures more (or less) accurately than healthy controls.4

Furthermore, many physicians lack sufficient training in occupational medicine, resulting in a failure to ask the "occupational question" during routine consultations.46 In the UK and France alike, the administrative burden of reporting and the fear of potential repercussions for the worker (such as job loss) create a culture of silence around work-related illnesses.48

8. Strategic Recommendations for Improving Identification

To modernize the recognition of occupational diseases and ensure equitable treatment for workers, several evidence-based improvements are proposed.

8.1 Adoption of the Six-Step Diagnostic Approach

The "Six-Step Approach" provides a structured, evidence-based algorithm for physicians to identify and report occupational diseases 6:

● Step 1: Determine the Disorder: Make a definitive clinical diagnosis.

● Step 2: Determine Relationship with Work: Understand the general association for the occupational group.

● Step 3: Determine the Nature and Level of Exposure: Quantify the hazard in the patient's specific environment.

● Step 4: Determine the Role of Individual/Non-Work Factors: Account for smoking, hobbies, or genetics.

● Step 5: Synthesize and Reach a Conclusion: Is it "more likely than not" (over 50 percent) that work caused the disease? 6

● Step 6: Prevention and Reporting: Use the diagnosis to trigger workplace safety improvements.

8.2 Sentinel Surveillance and Alert Systems

National registries in the EU often fail to monitor existing diseases or alert to new risks adequately.46 The implementation of "sentinel systems"—such as the French RNV3P or the Dutch NCOD—is vital.6 These networks involve university hospital experts who investigate suspicious cases and attribute "expert causality" to new disease-exposure signals.8 Such systems act as an "early warning" mechanism, allowing for the rapid detection of emerging threats (e.g., those from new chemical syntheses or psychosocial stressors) before they are formally codified into law.8

8.3 Digital Integration and Interoperability

The 2025 update to ICD-11 provides the technical framework for "smart" occupational health surveillance. Governments should incentivize the full integration of ICD-11's digital terminologies into primary care electronic health records (EHRs).11 This would allow for the automatic flagging of occupational risks based on a patient's job code (ISCO) and clinical findings, reducing the reliance on individual physician initiative and decreasing the impact of cognitive biases.10

8.4 Policy Harmonization and Training

Finally, there is an urgent need to harmonize the diagnostic and exposure criteria across European member states.9 Using the "European schedule of occupational diseases" (2022 recommendation) as a baseline would ensure that a worker’s access to compensation does not depend solely on their geography.9 This must be accompanied by mandatory occupational health training for all general practitioners and specialists, bridging the gap between clinical practice and the occupational origin of disease.46

9. Conclusion

The determination of whether a disease is truly occupational is a forensic process that requires a synthesis of clinical excellence, epidemiological evidence, and legal understanding. Through the lens of the WHO’s ICD-11 and the ILO’s 2025 updates, the global community has the tools to standardize this recognition. However, as the comparison between France and the United Kingdom demonstrates, the realization of these standards is deeply influenced by national philosophies of risk and solidarity.

While the French "Tableaux" system offers a high degree of certainty and protection for workers through the presumption of origin, the UK’s IIDB scheme provides a more focused, if administratively restricted, safety net. Both systems face the challenges of cognitive bias and structural underreporting. The future of occupational medicine lies in the adoption of structured diagnostic protocols, the expansion of sentinel surveillance networks, and the full utilization of digital health innovations. Only by improving the quality of the diagnostic process can societies fulfill their commitment to both the prevention of occupational illness and the fair compensation of those whose health has been sacrificed in the course of their professional duties.

References

1. Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefits: technical guidance - GOV.UK, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/industrial-injuries-disablement-benefits-technical-guidance/industrial-injuries-disablement-benefits-technical-guidance

2. Work-Relatedness - ACOEM, accessed January 11, 2026, https://acoem.org/acoem/media/News-Library/JOEM-Work-relatedness-Dec-2018.pdf

3. How are occupational diseases recognised and what is the role of the scientific expert appraisal? | Anses, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.anses.fr/en/content/how-are-occupational-diseases-recognised-and-what-is-the-role-of-the-scientific-expert-appraisal

4. Information bias: misclassification and mismeasurement of exposure and outcome - Statistical Methods in Cancer Research Volume V - NCBI, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK612868/

5. A Comprehensive Review of Injury Causation Analysis Methodology for the Assessment of Workers' Compensation and Motor Vehicle Collision Injuries - PMC - NIH, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11812656/

6. Improving the assessment of occupational diseases by occupational ..., accessed January 11, 2026, https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article/67/1/13/2445867

7. Understanding Causation - TN.gov, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.tn.gov/workforce/injuries-at-work/bureau-services/bureau-services/medical-programs-redirect/assistance-for-medical-providers/causation.html

8. Work-related diseases - findings from an EU-OSHA activity - SPF Emploi, accessed January 11, 2026, https://evenementen.werk.belgie.be/sites/default/files/content/events/2019/20191002-01-brussels_wrd_presentation-elke_schneider.pdf

9. Commission Recommendation concerning the European schedule ..., accessed January 11, 2026, https://osha.europa.eu/en/legislation/guidelines/commission-recommendation-concerning-european-schedule-occupational-diseases

10. European Occupational Diseases Statistics, accessed January 11, 2026, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/22020267/KS-01-25-024-EN-N.pdf/fffa28db-2767-eebc-27ad-e3f4be59b135?version=1.0&t=1754385671320

11. WHO releases 2025 update to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.who.int/news/item/14-02-2025-who-releases-2025-update-to-the-international-classification-of-diseases-(icd-11)

12. International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision in Occupational Health, accessed January 11, 2026, https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/classification/icd-11-webinars/occupational-health-webinar/icd-11-intro-occupational_catteam.pdf?sfvrsn=50369aac_5

13. 1658c The ilo list of occupational diseases and the who icd, accessed January 11, 2026, https://oem.bmj.com/content/75/Suppl_2/A230.3

14. ILO List of Occupational Diseases - International Labour Organization, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/media/336656/download

15. Occupational Disease Report Form - State of Michigan, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/lara/bpl/Shared-Files/MD-DO-POD/Occupational-Disease-Reporting-Instructions-for-MDs-and-DOs.pdf?rev=5801455b18354e4d96a1ea19b1dbcd02

16. Tableaux des maladies professionnelles - Publications et outils - INRS, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.inrs.fr/publications/bdd/mp.html

17. KEY FEATURES OF 2022 - Eurogip, accessed January 11, 2026, https://eurogip.fr/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/AMRP-Key-features-2022-health-and-safety-in-the-workplace.pdf

18. Tableaux des maladies professionnelles prévus à l'article R. 461-3 (Articles Annexe II - Légifrance, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/id/LEGISCTA000006126943

19. Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit: Eligibility - GOV.UK, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.gov.uk/industrial-injuries-disablement-benefit/eligibility

20. Bradford Hill criteria – Knowledge and References - Taylor & Francis, accessed January 11, 2026, https://taylorandfrancis.com/knowledge/Medicine_and_healthcare/Epidemiology/Bradford_Hill_criteria/

21. Causation in epidemiology: association and causation - Health Knowledge, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.healthknowledge.org.uk/e-learning/epidemiology/practitioners/causation-epidemiology-association-causation

22. Assessing causality in epidemiology: revisiting Bradford Hill to incorporate developments in causal thinking - PMC - NIH, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8206235/

23. bradford hill criteria: Topics by Science.gov, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.science.gov/topicpages/b/bradford+hill+criteria

24. Enhancing Diagnostic Accuracy in Occupational Medicine ..., accessed January 11, 2026, https://occupationalhealthlearner.com/enhancing-diagnostic-accuracy-in-occupational-medicine-recognizing-and-overcoming-cognitive-biases/

25. U.S. Department of Labor Evidence Required in Support of a Claim for Occupational Disease, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/owcp/regs/compliance/ca-35.pdf

26. Medical evidence and OWCP, Part 5 —The CA-2 for occupational disease - NALC, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.nalc.org/news/the-postal-record/2024/january-2024/document/Workers-Comp.pdf

27. Maladie professionnelle | ameli.fr | Médecin, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.ameli.fr/medecin/exercice-liberal/prise-charge-situation-type-soin/situation-patient-mp/maladies-professionnelles

28. Tips for Writing a Workers' Comp Causation Letter - Texas Medical Association, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.texmed.org/Template.aspx?id=45512

29. France vs Germany vs UK: Employee Benefits Compared - Brain Source International, accessed January 11, 2026, https://brain-source.com/comparison-employee-benefits-in-france-vs-germany-vs-uk

30. Why States Think about Risk Differently: The Case of Workplace Safety Regulation in France and the UK - ResearchGate, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319154349_Why_States_Think_about_Risk_Differently_The_Case_of_Workplace_Safety_Regulation_in_France_and_the_UK

31. Qu'est-ce qu'une maladie professionnelle ? | Service Public, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.service-public.gouv.fr/particuliers/vosdroits/F31880

32. MALADIES PROFESSIONNELLES (MP), accessed January 11, 2026, https://sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/maladies_professionnelles_mp.pdf

33. Methodological Note FR - European Commission, accessed January 11, 2026, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/7894008/12497131/FR-methodological-note.pdf

34. The European influence on workers' compensation reform in the United States - PMC, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3267658/

35. Health and safety at work in France: what will it be like in 2025? - Moovency, accessed January 11, 2026, https://moovency.com/en/health-and-safety-at-work-in-france-what-will-it-be-like-in-2025/

36. Rapport annuel 2024 de l'Assurance Maladie - Risques professionnels, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.assurance-maladie.ameli.fr/etudes-et-donnees/2024-rapport-annuel-assurance-maladie-risques-professionnels

37. About Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit - GOV.UK, accessed January 11, 2026, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/635a3cbad3bf7f0bdcedff9a/iidb1-easy-read-oct-2022.pdf

38. Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit: A guide to claiming IIDB | Slater + Gordon, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.slatergordon.co.uk/newsroom/a-guide-to-claiming-industrial-injuries-disablement-benefit/

39. Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit | nidirect, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/industrial-injuries-disablement-benefit

40. Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit (IIDB) - Health Assessment ..., accessed January 11, 2026, https://haas-serco.co.uk/iidb/

41. Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit | Understanding benefits | RCN Welfare Service, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.rcn.org.uk/Get-Help/Member-support-services/Welfare-Service/Understanding-benefits/Industrial-Injuries-Disablement-Benefit

42. An international comparison of occupational disease and injury compensation schemes - GOV.UK, accessed January 11, 2026, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7d84afed915d3fb9594400/InternationalComparisonsReport.pdf

43. Comparisons with other European countries - HSE, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/european/index.htm

44. Health-related benefit claims post-pandemic: UK trends and global context, accessed January 11, 2026, https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/2025-04/Health-related-benefit-claims-post-pandemic_3_1.pdf

45. Health-related benefit claims post-pandemic: UK trends and global context, accessed January 11, 2026, https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/2024-09/Health-related-benefit-claims-post-pandemic_1.pdf

46. Evaluation of occupational disease surveillance in six EU countries - Oxford Academic, accessed January 11, 2026, https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article/60/7/509/1418664/Evaluation-of-occupational-disease-surveillance-in

47. Bias in occupational studies | Request PDF - ResearchGate, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6742847_Bias_in_occupational_studies

48. Global trends in occupational disease reporting: a systematic review - medRxiv, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.09.19.24314032v1.full.pdf