Investigate burnout, psychosocial hazards, violence against workers, harassment and strategies for resilience

1. Dr.Turusbekova Akshoola Kozmanbetovna

2. Pulkit Sharma

(Teacher, International Medical Faculty, Osh State university, Kyrgyzstan

Student, International medical faculty, Osh State university, Kyrgyzstan)

Abstract

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the intersection between psychosocial hazards and biological risks in the modern workplace, with a specific focus on the healthcare sector. It examines the theoretical foundations of psychosocial risk, the prevalence and systemic drivers of burnout, and the psychological impact of workplace violence. Furthermore, it details evidence-based assessment methodologies, including ISO 45003 and the HSE Management Standards. The report also addresses the management of occupational infections—specifically Tuberculosis, Hepatitis, and COVID-19—through integrated prevention programs and the critical appraisal of individual versus organizational resilience strategies.

Keywords: Burnout, Psychosocial Hazards, Occupational Health, Infection Prevention, Workplace Violence, ISO 45003, Healthcare Workers, Resilience Engineering.

The modern professional landscape is currently navigating a fundamental paradigm shift in the conceptualization and management of occupational health. This evolution is characterized by a transition from a traditional, narrow focus on physical safety—primarily concerned with mechanical, chemical, and ergonomic hazards—to a holistic biopsychosocial framework.1 This contemporary perspective recognizes that the health and integrity of a workforce are the products of complex, intersecting dynamics between biological risks, such as infectious diseases; psychological stressors, including burnout and emotional exhaustion; and social variables, encompassing workplace culture and interpersonal conflicts.1 As global economies grapple with the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the rapid digitalization of work, the prevalence of psychosocial hazards has escalated, frequently posing a more significant threat to organizational sustainability and individual well-being than conventional physical dangers.3

The Theoretical Foundations of Psychosocial Risk and Occupational Stress

To understand the current crisis in workforce well-being, it is necessary to examine the theoretical models that define the relationship between work design and psychological health. Psychosocial risks are not merely individual reactions to pressure but are rooted in the design, organization, and management of work.3 Central to this understanding are established organizational models such as Karasek’s Job Strain Model and the Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) model.6 Karasek’s model posits that the highest levels of psychological strain occur when high job demands are coupled with low decision-making autonomy or control.6 Similarly, the ERI model suggests that a lack of reciprocity between the effort expended by a worker and the rewards received—such as pay, esteem, or career opportunities—leads to chronic stress and increased burnout risk.6

These theoretical underpinnings are increasingly relevant as the world of work transitions toward remote and hybrid models. While these arrangements offer flexibility, they have simultaneously introduced stressors like digital overload, social isolation, and the emergence of an "always-on" culture.4 This culture, where employees feel an implicit or explicit compulsion to remain available outside standard working hours, has been directly linked to heightened stress and a diminished work-life balance (WLB).4 Consequently, the management of psychosocial hazards has moved from a moral obligation to a strategic necessity for maintaining organizational resilience.3

Burnout: Dimensions, Prevalence, and Systemic Drivers

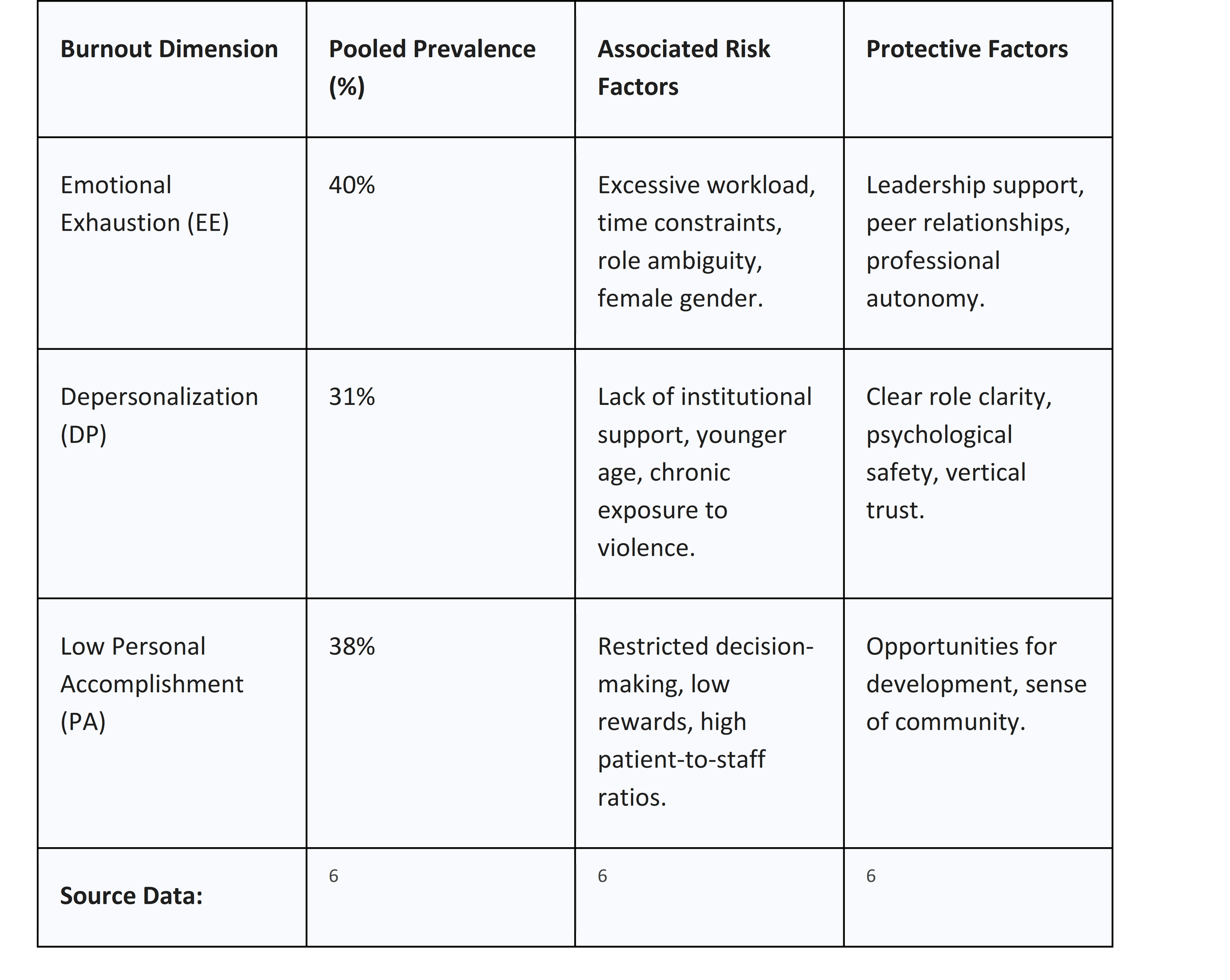

Burnout is a multifaceted syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress that has been unsuccessfully managed. It is formally characterized by three primary dimensions as defined in the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI): emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and a sense of diminished professional efficacy or low personal accomplishment (PA). While burnout is a risk across all sectors, its prevalence is particularly high in "helping" professions such as healthcare and education, where professionals are exposed to constant interpersonal stressors and high emotional demands.6

A recent large-scale meta-analysis involving over 36,000 healthcare workers across the Middle East, North Africa, and Turkey (MENAT) region highlights the alarming scale of the problem. This study found a pooled prevalence of 40% for high emotional exhaustion, 31% for high depersonalization, and 38% for low personal accomplishment.6 These figures vary significantly based on national infrastructure and workforce conditions, with notably higher rates in countries experiencing systemic healthcare strain such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Turkey.6

Table 1: Prevalence and Correlates of Burnout in the Healthcare Sector

The implications of burnout extend far beyond individual distress. In clinical environments, high levels of burnout are intrinsically linked to the erosion of patient safety and a deterioration in the quality of care.8 Research suggests a 66.4% probability of superiority regarding the relationship between burnout development and negative patient safety actions.8 Burnout triggers a mechanism of failure where professionals, particularly nurses and physicians, become cold or cynical toward patients' needs, leading to an increase in medical errors and formal patient complaints.8 Furthermore, burnout places an immense economic burden on healthcare systems due to increased workforce turnover, absenteeism, and heightened malpractice risks.6

Structural Hazards: Workplace Violence and Harassment

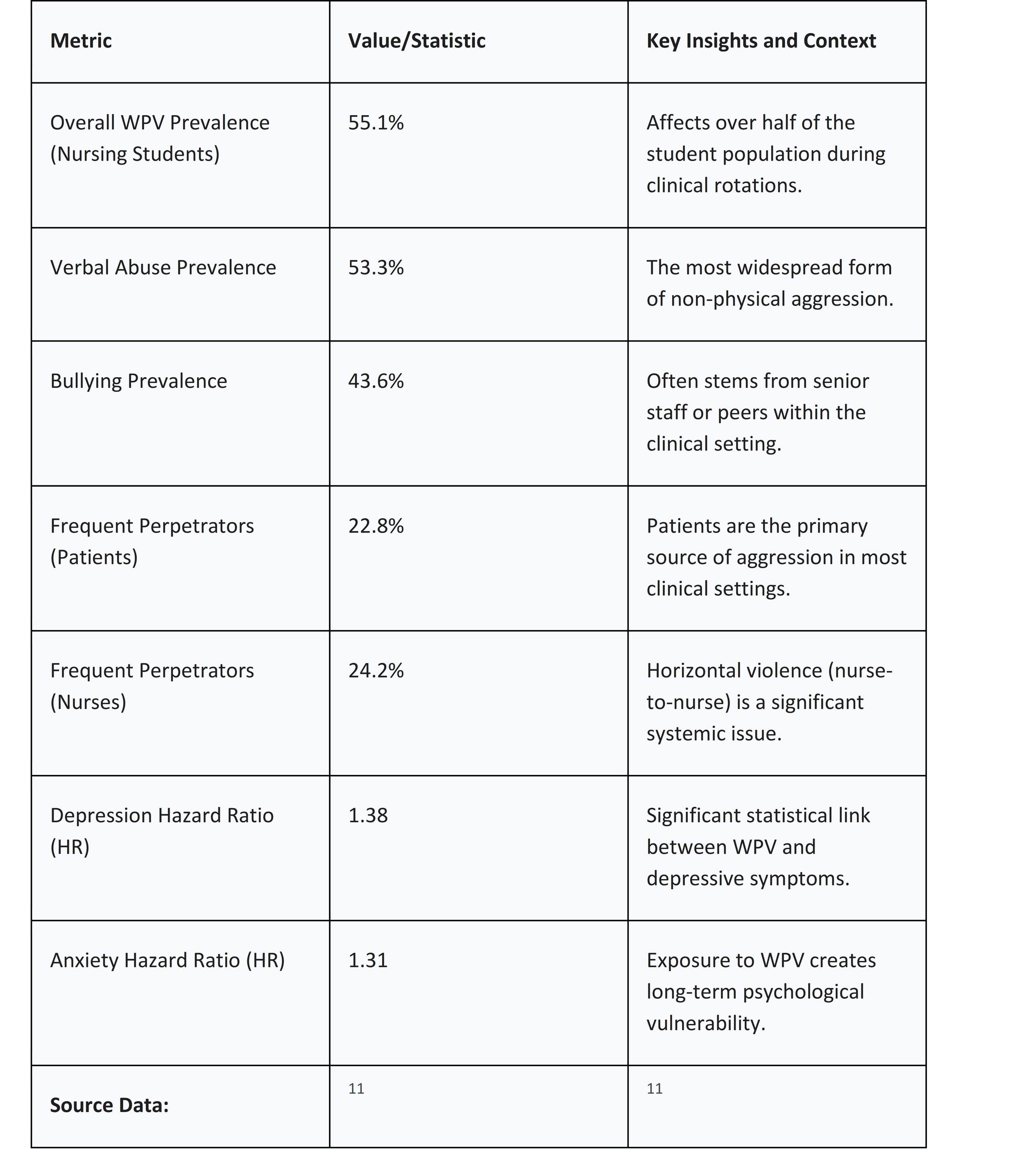

Workplace violence (WPV) and harassment represent a paradigmatic form of structural occupational hazard. WPV encompasses a spectrum of unacceptable behaviors, including physical assault, verbal abuse, intimidation, and sexual harassment. These incidents are particularly common in high-risk settings such as emergency departments, psychiatric wards, and pediatric units. For nursing students, the risk is especially acute, with global data indicating that 55.1% of students encounter some form of violence during clinical training.10

The psychological toll of WPV follows a clear dose-response relationship: as the frequency and severity of the violence increase, so do the risks of mental health disorders.11 For example, nurses experiencing WPV face a 38% increased risk of depression (HR = 1.38) and a 31% increased risk of anxiety (HR = 1.31).11 Chronic exposure to aggression undermines a worker’s sense of professional altruism and control, often acting as the primary driver for high turnover rates and the early exit of experienced staff from the profession.

Table 2: Prevalence and Impacts of Workplace Violence (WPV) in Nursing

International standards have evolved to provide a legal and ethical framework for addressing these hazards. The ILO Violence and Harassment Convention, 2019 (No. 190), provides the first international treaty to recognize the right of everyone to a world of work free from violence and harassment.12 This framework mandates a gender-responsive approach that addresses underlying causes such as gender stereotypes and unequal power relations.12 Employers are encouraged to establish zero-tolerance policies that cover all workers, visitors, and contractors, ensuring that all reports are investigated promptly and with strict confidentiality.

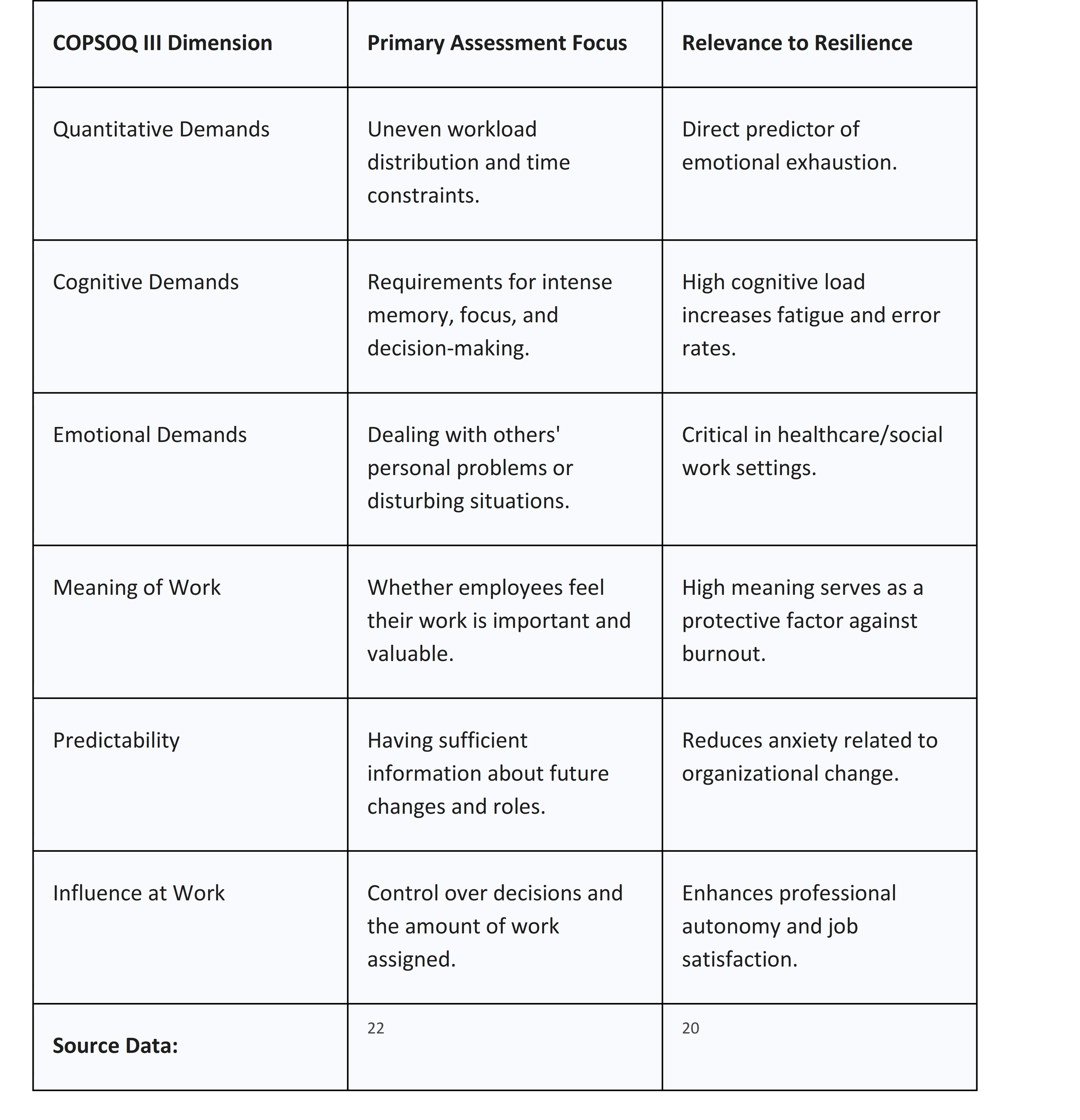

Methodologies for Psychosocial Risk Assessment

To manage psychosocial hazards effectively, organizations must employ rigorous, evidence-based assessment methodologies. These tools allow for the identification of root causes of stress and the prioritization of interventions.

ISO 45003: International Guidelines for Psychological Health

ISO 45003 is the first international standard focused on managing psychological health and safety at work.16 It is designed to work in conjunction with ISO 45001, providing a structured framework to identify, assess, and manage psychosocial risks as part of a broader occupational health and safety (OHS) management system.17 The standard categorizes hazards into three core areas:

1. Work Organization: This includes factors such as workload, job demands, role clarity, and how work is managed.5

2. Social Factors: This covers interpersonal relationships, workplace culture, leadership quality, and communication.5

3. Work Environment and Equipment: This addresses physical factors like unsafe conditions, poor equipment, and the nature of hazardous tasks.5

Implementation of ISO 45003 follows the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle, emphasizing that top management must proactively demonstrate a "culture of care" by making resources available and protecting workers from reprisals when reporting risks.5

HSE Management Standards and the Stress Indicator Tool (SIT)

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) in the United Kingdom established the Management Standards to define the primary sources of work-related stress. The SIT is an online 35-question survey that assesses performance across six key areas of work design: demands, control, support, relationships, role, and change.18

Validation studies in countries such as Australia and Turkey have demonstrated the tool's reliability in identifying the top predictors of employee mental health, such as job insecurity and burnout.

Occupational Infectious Diseases: TB, Hepatitis, and COVID-19

Biological hazards represent a severe risk to workforce health, particularly for those in medical, emergency response, and public service sectors. The management of these risks requires a sophisticated integration of clinical knowledge and OHS principles.24

Tuberculosis (TB) in Healthcare Environments

Tuberculosis remains a leading cause of global morbidity, spread primarily through aerosol droplets released when an infected person coughs or speaks.24 Healthcare workers are at a significantly higher risk, with latent TB rates reaching 54% in low- and middle-income countries.25

A comprehensive TB infection control program must prioritize the hierarchy of controls. Engineering interventions, such as high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration and ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI), are critical.24 A landmark study demonstrated that UVGI fixtures, combined with fans to ensure even air circulation, reduced TB transmission by 70%.28 In terms of personal protective equipment (PPE), there is a stark difference in efficacy: surgical masks offer minimal protection (18.4% filtration efficiency) compared to N95 respirators (97.4% efficiency).28 Furthermore, the introduction of molecular diagnostic tools like the Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra test allows for the rapid identification of cases, facilitating early isolation and reducing nosocomial spread.28

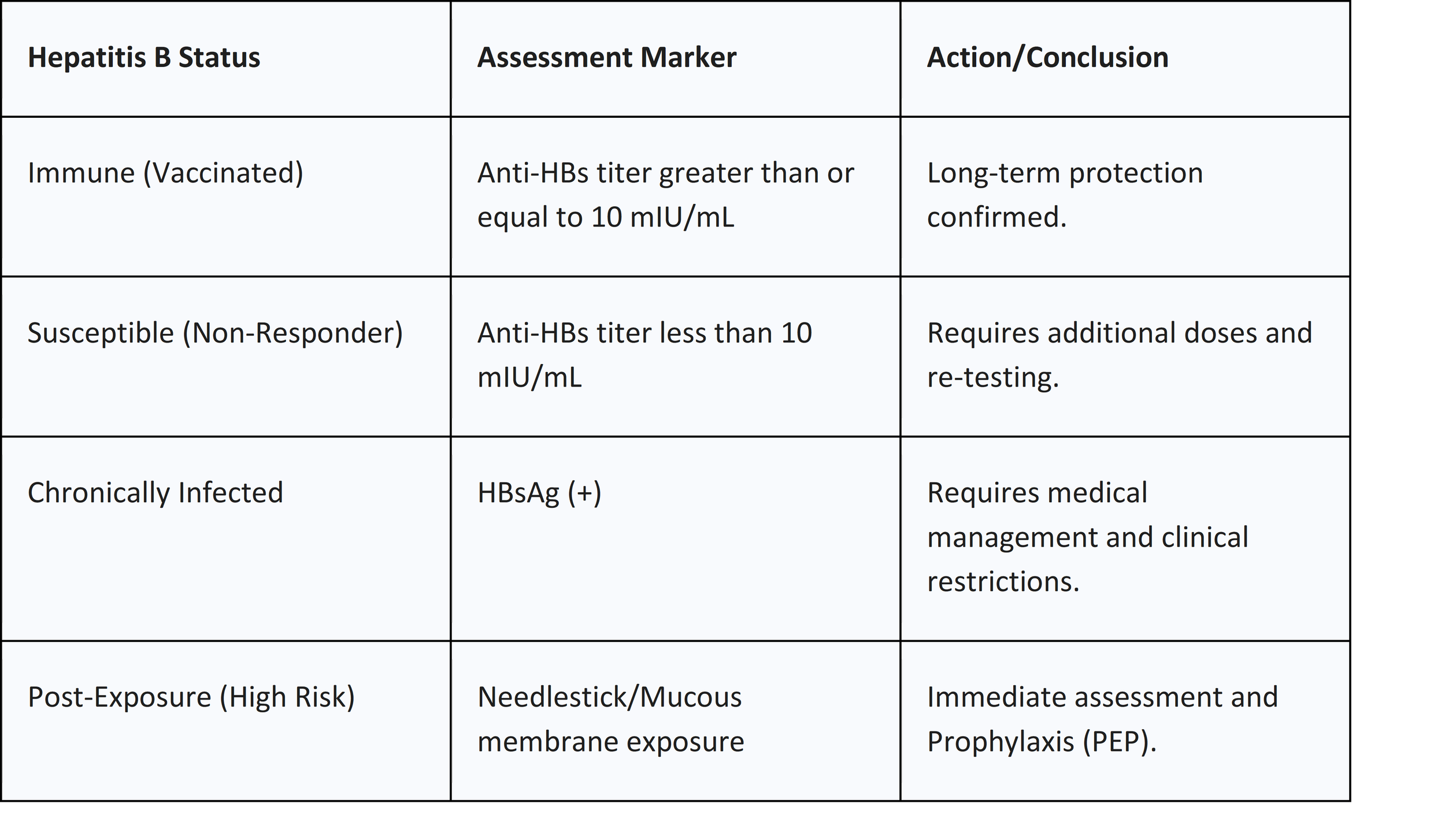

Hepatitis B and C: Bloodborne Pathogens and Vaccination Efficacy

Hepatitis viruses are major occupational concerns, primarily transmitted through needlestick and sharp injuries.24 Needlestick incidents contribute to 37% of hepatitis B and 39% of hepatitis C infections among health workers.25

Vaccination is the cornerstone of hepatitis B prevention. While standard 3-dose vaccine regimens (administered over 6 months) are highly effective, the newer 2-dose HepB-CpG vaccine (administered over 1 month) has shown faster seroprotection and may improve compliance rates among new healthcare entrants.29 Persistence of humoral immunity is high; approximately 73.8% of vaccinated individuals maintain seroprotection for over two decades, though challenge doses may be required for those who drop below protective levels.30

COVID-19: Lessons from Pandemic Management

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic underscored the importance of an integrated approach to OHS. Frontline workers faced a 12-fold increased risk of infection compared to the general community.32 However, critical research suggests that staff-to-staff transmission—often occurring in non-clinical areas like breakrooms or during shared meals—was a major contributor to hospital outbreaks.32

Effective COVID-19 control requires a multi-layered strategy:

● Engineering Controls: Physical barriers, stanchion systems, and improved ventilation.

● Administrative Controls: Mandatory masking, social distancing, and rigorous contact tracing.32

● Behavioral Motivation: Assessing staff perceptions of IPC protocols and encouraging a "leading by example" approach from senior leadership.32

Strategies for Resilience: Individual vs. Organizational Approaches

Resilience in the workplace is the capacity to adapt and recover from stressors while maintaining organizational functioning.34 There is a critical, often-overlooked tension between individual resilience (IR) and organizational resilience (OR).7

The Efficacy and Limitations of Individual Resilience Interventions

Individual-level interventions often focus on empowering workers through stress management and psychological skills. Systematic reviews indicate that person-directed psychoeducational programs—including mindfulness-based interventions, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) approaches, and relaxation techniques like art therapy—can effectively reduce immediate levels of burnout, anxiety, and stress.

However, these interventions have significant limitations. They often do not address the systemic work design issues that cause stress, such as chronic understaffing or toxic leadership. Relying solely on IR can lead to a culture where the burden of managing workplace-induced stress is placed entirely on the employee, potentially overlooking the need for environmental change.

Strengthening Organizational Resilience

Organizational resilience involves creating supportive environments that prevent stress from occurring. This includes the provision of "slack resources" (extra time or personnel), systematic learning from failures, and fostering vertical trust.

There is evidence that organizational factors such as supervisor support and procedural justice are adjustment variables that moderate the impact of individual resilience on health outcomes.36 A resilient individual in a non-resilient organization is still at high risk of burnout.

Prevention Program Design and Integrated OHS-WHP Models

The most effective prevention programs adopt an integrated approach that combines Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) with Workplace Health Promotion (WHP).37 While OHS focuses on changing the work environment (e.g., controlling biological or psychosocial hazards), WHP aims to improve individual health behaviors (e.g., encouraging vaccinations, exercise, and diet).37

Steps for Effective Prevention Program Design

1. Comprehensive Risk Assessment: Use validated tools like the HSE SIT or COPSOQ III to map physical, biological, and psychosocial hazards.

2. Leadership Commitment: Senior management must provide a formal "statement of commitment" and ensure that health is integrated into all business processes.

3. Worker Participation: Consultation with workers and their health and safety representatives (HSRs) is essential to ensure that programs address actual needs.3

4. Application of the Hierarchy of Controls: Prioritize the elimination of hazards over the use of PPE.

5. Multi-Level Interventions: Combine primary (risk reduction), secondary (training/awareness), and tertiary (EAPs/counseling) interventions.16

6. Continuous Monitoring and Evaluation: Use real-time dashboards and regular surveys to track improvements and adapt to new stressors.

Case Study: Poor Organizational Change Management

An investigation into an Australian Public Service agency provides a cautionary example of failed program design. The agency implemented a new performance management system without consulting contract staff, leading to a foreseeable increase in stress, bullying, and mental health injuries.39 The corrective action plan required the agency to integrate all workers into the consultation process and develop a system to identify psychological hazards before future organizational changes.39

Critical Appraisal of Workforce Health Research

A critical appraisal of current literature reveals both strengths and significant gaps. Much of the research on burnout and workplace violence is cross-sectional, making it difficult to establish clear causal relationships. There is a pressing need for longitudinal studies that track the long-term effectiveness of integrated interventions.

Furthermore, many studies rely heavily on the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). While validated, it may not capture all the nuances of modern, digitally-driven work stress. Future research must also account for geographic and cultural disparities; for instance, the Latin American perspective and the specific challenges faced in sub-Saharan Africa are often under-represented in major meta-analyses.6

In terms of infection control, the pandemic highlighted a "knowledge-practice gap," where high levels of knowledge did not always translate into strict compliance with infection prevention and control (IPC) protocols.32 This suggests that training programs must move beyond "how" to do a procedure and focus on "why" it is necessary, addressing the social and behavioral drivers of compliance.32

Strategic Conclusions and Workforce Outlook

The integration of psychosocial and biological risk management is no longer optional in a complex, globalized economy. The evidence suggests that a safe and resilient world of work is built on three pillars:

First, the recognition of psychosocial integrity as a fundamental human right and a core component of OHS.12 This requires the adoption of international standards like ISO 45003 and a proactive approach to eliminating structural violence and harassment.

Second, the implementation of robust, science-based infection control. This involves prioritizing high-efficiency engineering controls—such as UVGI and N95 respirators—over less effective administrative measures, and ensuring that vaccination programs are accessible and modernized for all staff levels.28

Third, the development of integrated resilience frameworks. Organizations must balance the empowerment of the individual with the systemic improvement of work design. A culture of trust, leadership support, and professional autonomy is the most potent defense against the epidemic of burnout and the erosion of workforce health.

In conclusion, the future of occupational health depends on the ability of organizations to move beyond reactive crisis management. By employing rigorous risk assessment, fostering a culture of mutual respect, and committing to continuous, evidence-based improvement, employers can ensure that work remains a source of health and dignity.

References -

1. The Importance of a Biopsychosocial Approach to Work Health and Safety: Embracing a Holistic Perspective, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://agestrong.com.au/our-insights/the-importance-of-a-biopsychosocial-approach-to-work-health-and-safety-embracing-a-holistic-perspective/

2. A GUIDE TO ISO 45003 - ASSP, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.assp.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/iso_45003_tech_report_final_210703.pdf

3. Psychosocial risks and mental health at work, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://osha.europa.eu/en/themes/psychosocial-risks-and-mental-health

4. Psychosocial hazards and work-life balance: the role of workplace conflict, rivalry, and harassment in Latvia - Frontiers, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1494288/full

5. Introduction to ISO 45003: Managing Psychosocial Risk in the Workplace, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://risktrainingprofessionals.com/blog/2025/03/06/introduction-to-iso-45003-managing-psychosocial-risk-in-the-workplace/

6. Prevalence of burnout and its risk and protective factors ... - Frontiers, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1539105/full

7. Investigating the Connection Between Individual Resilience and Organisational Resilience - MDPI, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.mdpi.com/2079-8954/13/10/907

8. Influence of Burnout on Patient Safety: Systematic Review and Meta ..., accessed on January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6780563/

9. Psychoeducational Burnout Intervention for Nurses: Protocol for a Systematic Review - NIH, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11474121/

10. Global prevalence and factors associated with workplace violence against nursing students: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression - ResearchGate, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377096951_Global_prevalence_and_factors_associated_with_workplace_violence_against_nursing_students_A_systematic_review_meta-analysis_and_meta-regression

11. Workplace violence predicts depression and anxiety in nurses: a multi-center longitudinal study in China - PubMed Central, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12625131/

12. Eliminating Violence and Harassment in the World of Work - International Labour Organization, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/media/406901/download

13. Safe and healthy working environments free from violence and harassment - International Labour Organization, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@safework/documents/publication/wcms_751832.pdf

14. How to prevent and address violence and harassment at work: A ..., accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/2024-11/%282024%29%20VH%20training%20manual%20for%20enterprises-Final%20%281%29.pdf

15. Addressing gender-based violence and harassment in a work health and safety framework - Astrid-online.it, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.astrid-online.it/static/upload/wp11/wp116_web.pdf

16. Psychological Health and Safety Management System Self-Assessment - BSI, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.bsigroup.com/siteassets/pdf/en/insights-and-media/insights/brochures/nz-as-cross-brand-os-ot-mpd-mp-bsibrand-0025-social45003-selfassessment.pdf

17. Certification ISO 45003 – Psychological health and safety in the workplace - RINA.org, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.rina.org/en/iso-45003

18. Stress Indicator Tool (SIT) - HSE Books, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://books.hse.gov.uk/stress-indicator-tool-sit

19. Questionnaire Review: Management Standards Indicator Tool - PMC, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12257939/

20. A Validation Study of the COPSOQ III Greek Questionnaire for Assessing Psychosocial Factors in the Workplace - PMC - NIH, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12385713/

21. Validation and benchmarks for the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ III) in an Australian working population sample, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.copsoq-network.org/assets/pdf/2025/Validation-COPSOQ-III-Australia-Arnold-2025.pdf

22. COPSOQ III Questionnaire Overview | PDF | Action (Philosophy) - Scribd, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.scribd.com/document/451122827/COPSOQ-III-questionnaire-060718

23. The Third Version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire - COPSOQ network, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.copsoq-network.org/assets/Uploads/The-Third-Version-of-the-Copenhagen-Psychosocial-Questionnaire.pdf

24. Infectious Agents Risk Factors | Healthcare Workers - CDC, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/healthcare/risk-factors/infectious-agents.html

25. Occupational Exposure to Infectious Diseases among Health Workers: Effects, Managements and Recommendations - ClinMed International Library, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://clinmedjournals.org/articles/jide/journal-of-infectious-diseases-and-epidemiology-jide-9-295.php/1000

26. Lessons Learned During the COVID-19 Pandemic to Strengthen TB Infection Control: A Rapid Review | Global Health: Science and Practice, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/9/4/964

27. Occupational infections - World Health Organization (WHO), accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.who.int/tools/occupational-hazards-in-health-sector/occupational-infections

28. Strategies for Tuberculosis Prevention in Healthcare Settings: A ..., accessed on January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12656276/

29. Full article: Preventing hepatitis B virus infection among healthcare professionals: potential impact of a 2-dose versus 3-dose vaccine, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21645515.2021.1965807

30. Long-Term Effectiveness of Hepatitis B Vaccination in the Protection of Healthcare Students in Highly Developed Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9695994/

31. CDC Guidance for Evaluating Health-Care Personnel for Hepatitis B Virus Protection and for Administering Postexposure Management, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6210a1.htm

32. Successfully addressing non-compliance with behavioral and social infection control measures is a critical component in management of healthcare worker COVID-19 outbreaks: learning outcomes from the first staff outbreak in the main maternity hospital in Qatar - Frontiers, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1534421/full

33. COVID-19 - Control and Prevention | Occupational Safety and Health Administration - OSHA, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.osha.gov/coronavirus/control-prevention

34. Building Organizational Resilience Through Organizational Learning: A Systematic Review - Frontiers, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/communication/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2022.837386/full

35. (PDF) Individual and Organizational Resilience: Relationships, Antecedents, and Consequences - ResearchGate, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388750977_Individual_and_Organizational_Resilience_Relationships_Antecedents_and_Consequences

36. Resilience and occupational health of health care workers: a moderator analysis of organizational resilience and sociodemographic attributes - NIH, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8170862/

37. Identification of needs of integrated approaches of occupational health and safety and health promotion - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12450578/

38. Steps to a Healthier US Workforce: Integrating Occupational Health and Safety and Worksite Health Promotion - CDC Stacks, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/181615/cdc_181615_DS1.pdf

39. Psychosocial hazard case studies - Comcare, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.comcare.gov.au/safe-healthy-work/prevent-harm/psychosocial-hazards/whs-regulations-case-studies

40. How to Conduct a Psychosocial Risk Assessment in 2026 | Step-by-Step Guide - SafetySuite, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://www.safetysuiteglobal.com/post/psychosocial-risk-assessment-guide

41. Knowledge of infection prevention and control among healthcare workers and factors influencing compliance: a systematic review - PubMed Central, accessed on January 12, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8173512/